Negative interest rates matter for bank performance. When interest rates turn negative, banks suffer. This is because retail deposit rates are stuck at zero. Consistent with the deposits channel of monetary policy, banks that are relatively dependent on deposit funding are hurt more, and more persistently, by negative rates. The design of monetary policy can take this into account. Central bank instruments that target the longer-end of the yield curve are less detrimental to bank performance than those that target the shorter-end in times of negative interest rates. Therefore, quantitative easing and yield curve control deserve special consideration when interest rates are negative and further monetary accommodation is required.

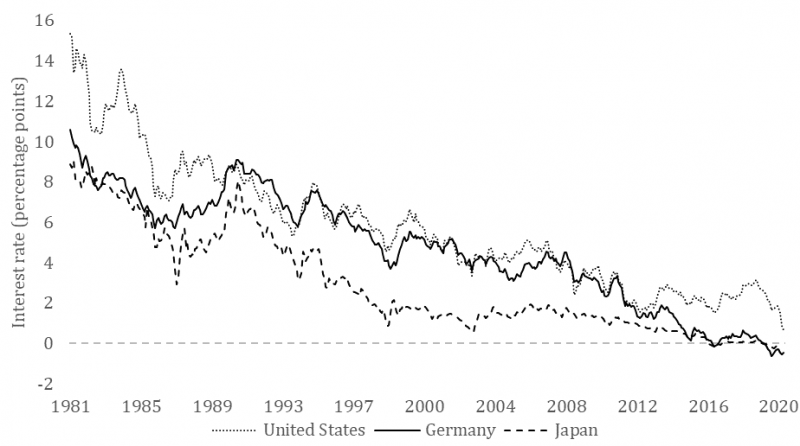

Over the past 40 years, interest rates have steadily declined worldwide, recently turning negative in Europe and Japan (Figure 1). In Europe and Japan, interest rates are expected to remain negative and yield curves flat for long. A prolonged period of negative interest rates has adverse implications for the performance of banks, as retail deposit rates are sticky at zero. In a negative interest rate environment, additional rate cuts may reduce bank profits, particularly if these endure. This can lead to financial instability (Porcellacchia, 2020) and `reverse’ accommodative monetary policy by reducing the lending capacity of capital-constrained banks (e.g. Borio and Gambacorta, 2017, Brunnermeier and Koby, 2018, Gomez et al., 2020).

Figure 1: 10-year government bond yield developments

Data source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

The question arises which central bank instruments can best be applied when interest rates are negative but further monetary stimulus is needed. We address this question by analyzing bank performance following different monetary policy actions (Bats et al., 2020). We find that instruments that target the longer-end of the yield curve are least detrimental to bank performance in times of negative interest rates. This policy note summarizes our findings and is structured as follows. First, we illustrate how negative interest rates could affect bank profits. Second, we translate bank profitability into a forward-looking measure of bank performance. Third, we analyze the varying effects of monetary policy instruments on our measure of bank performance. Fourth, we discuss our findings and show they are consistent with the deposits channel of monetary policy. Finally, we provide monetary policy considerations.

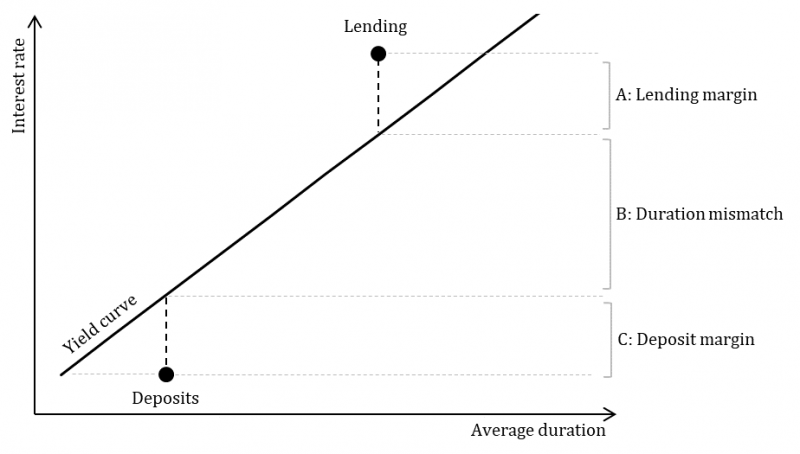

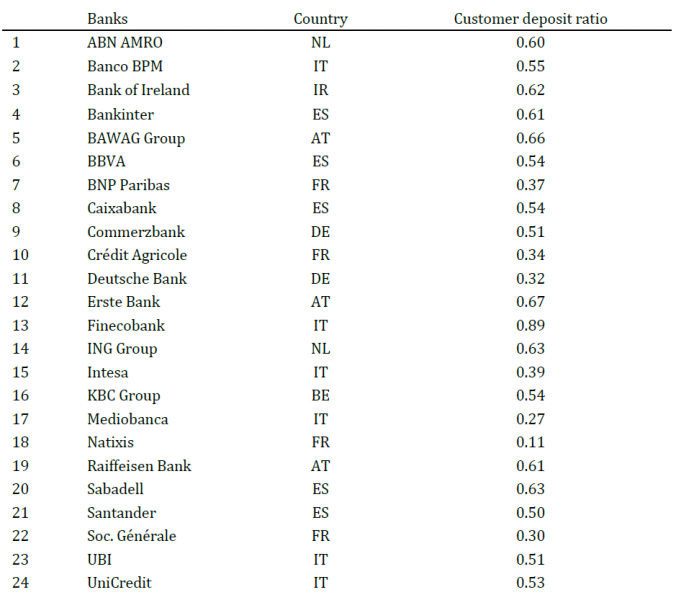

How do negative interest rates affect bank profitability? To understand this, the development of bank profits can be analyzed on the basis of banks’ net interest margins. In practice, banks replicate portfolios of fixed-rate assets that match the estimated duration of their deposit liabilities (Kalkbrener and Willing, 2004) using interest rate swaps (Jarrow and van Deventer, 1998). Deposits have a positive duration, because despite customers’ ability to clear their sight deposit balances at any point in time, they are a stable funding source for banks.1 The difference between the swap and deposit rate is the deposit margin (Figure 2, bracket C). While banks may supply loans with an average duration longer than their replicating portfolio (Figure 2, bracket B), the remaining interest rate exposure is generally hedged (Drechsler et al., 2018, Hoffmann et al., 2019). In addition, banks earn profits through lending: the lending margin is defined as the difference between the rate on lending and swap contracts with an equivalent average duration (Figure 2, bracket A).

Figure 2: The net interest margin of deposit banks

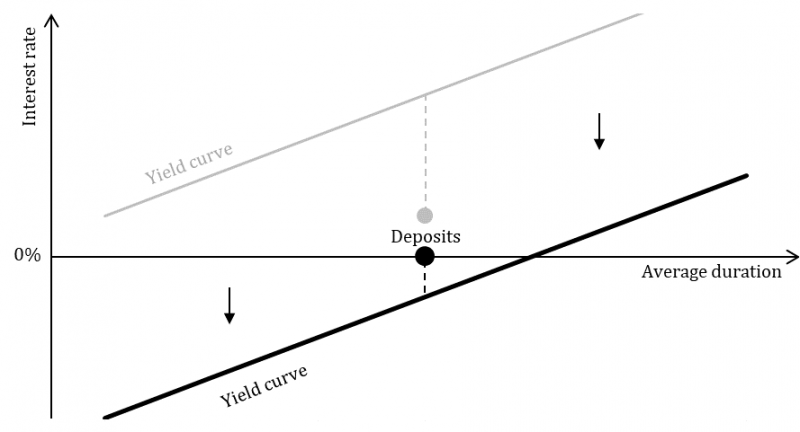

Once the interest rate environment turns negative, the income banks earn through retail deposits disappears. This is because retail deposit rates are bound at zero. Indeed, when the yield curve shifts downward in a negative interest rate environment, the deposit margin shrinks and eventually turns negative (Figure 3). By contrast, negative rates do not reduce the profits banks make through lending, because the lending margin mainly represents a credit risk premium and is not constrained by a lower bound. In practice, the lending margin may even temporarily increase thanks to a delayed decline in interest income on account of banks’ fixed rate assets having a longer duration (i.e. accruing capital gains).

Figure 3: The deposit margin of banks in a negative interest rate environment

A measure of bank performance

On the basis of reported data on bank profitability and the net interest margin, a low and negative interest rate environment has been shown to have adverse effects on bank performance (e.g. Claessens et al., 2018, Heider et al., 2019). But the use of reported data implies these studies are backward-looking and only respond to a drop in the interest rate with a lag due to banks’ capital gains on fixed rate assets. In terms of the sustainability of bank profits, backward-looking indicators may in fact be biased, as banks sometimes respond to negative interest rates by temporarily increasing their lending volumes (e.g. Demiralp et al., 2019, Tan, 2019). A prolonged period of negative interest rates may eventually require banks to increase lending margins, which will reduce their lending volumes, market share and profits.

To address these caveats, we explore the impact of negative interest rates on bank performance using a forward-looking indicator: bank stock prices. These reflect the market valuation of banks’ equity based on the expected future discounted cash flows at any given time. We investigate whether monetary policy surprises impact bank stock prices differently in times of positive and negative interest rates. As bank stock prices may anticipate changes to the yield curve in the future, unanticipated changes (i.e. surprises) in interest rates and bank stock prices are identified with high-frequency data around 269 ECB monetary policy announcements from January 1999 to January 2020.2

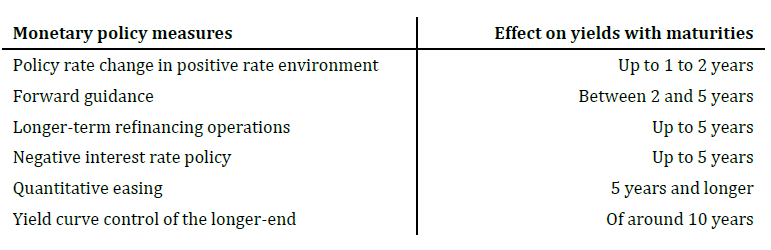

Assessing the impact of monetary policy on bank stock prices has the advantage of focusing on a forward-looking measure of bank performance. Given the introduction of unconventional monetary policy instruments, it is important to make a distinction between the different instruments central banks use to intervene on different segments of the yield curve (Table 1). Shorter-term yields, with maturities up to 5 years, are mostly affected by changing the central bank policy rate, providing forward guidance on a central bank’s future monetary policy intentions, offering central bank longer-term refinancing operations and introducing a negative interest rate policy. By contrast, longer-term yields, with maturities above 5 years, are mostly affected by quantitative easing and yield curve control policies that aim at controlling the longer-end of the yield curve.3

Table 1: Monetary policy instruments and their effects on the yield curve

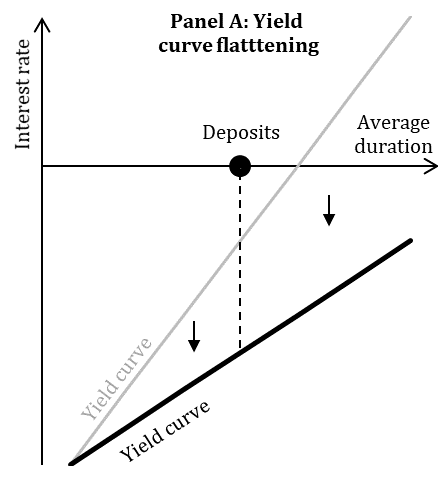

Bank performance may react differently to changes to the shorter- versus the longer-end of the yield curve, because deposit margins are relatively unaffected by changes to longer-term interest rates. To illustrate this, Figure 4 depicts the stylized impact on banks’ deposit margin of a flattening of the entire yield curve versus a flattening of only the longer-end of the yield curve. In a negative interest rate environment, a flattening of the entire yield curve can turn the deposit margin more negative, as banks match the duration of deposits with replicating portfolios (Figure 4, Panel A). By contrast, the deposit margin may be less affected if only the longer-end of the yield curve flattens (Figure 4, Panel B).

Figure 4: Monetary policy effects and the deposit margin when interest rates are negative

|

|

To investigate whether bank performance reacts differently to changes to the shorter- versus the longer-end of the yield curve, we estimate the effects of the following monetary surprises (in basis points) to the risk-free yield curve:

The dependent variables are monetary surprises (in percentage points) to a European bank stock index.

We employ rolling regressions to provide insight into how the impact of monetary policy on bank stock prices accrues over time as interest rates turn more negative. The regressions control for broad stock market movements to identify the specific disadvantage banks face in times of negative interest rates. The broad stock market is assumed to also react to unexpected interest rate changes (e.g. affecting capital value, future discount rates and/or equity premiums, economic activity) and their resulting macroeconomic signaling effects, while being insensitive to the specific additional negative effect of interest rate declines, which banks specifically face in times of negative interest rates.

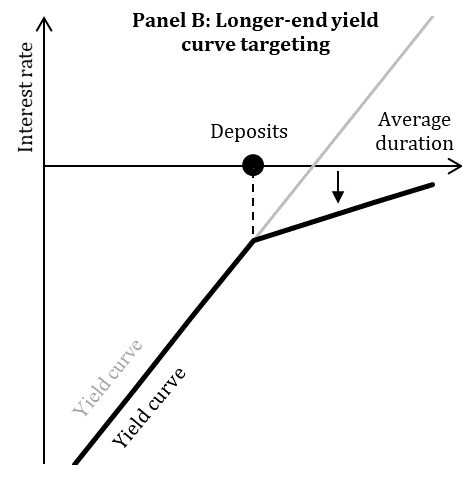

Our baseline results show that a low and especially negative interest rate environment hurts bank stock prices. Controlling for the broad stock market, a negative 10 basis points surprise to either the level or just the shorter-end slope of the yield curve reduces bank stock prices by more than 2 percentage points once the interest rate environment is negative (Figure 5, Panels A and B). We find that these effects persist in the days after the monetary policy announcement. By contrast, a surprise to only the longer-end slope of the yield curve does not impact bank stock prices when interest rates are negative (Figure 5, Panel C).

Figure 5: The varying effects of monetary policy on bank stock prices

Source: Bats et al. (2020)

Note: This figure shows rolling effects on European bank stocks of yield curve surprises following ECB monetary policy announcements. The estimations are run over fixed windows of 48 observations, such that the last window covers the maximum period from the introduction of the ECB’s negative interest rate policy in June 2014 until the most recent available date in the sample. As monetary Eurosystem meetings occur less frequently over time, the fixed window period widens. The dependent variable measures intraday movements in the log of the bank stock index (SX7E). Panel A shows the rolling effect of a level surprise to the yield curve. Panel B shows the rolling effect of a surprise to the difference between the 5-year and 1-month rate. Panel C shows the rolling effect of a surprise to the difference between the 10- and 5-year rate. Intraday movements in the log of the broad stock market index (STOXX50) and (T)LTRO announcements are controlled for. The dotted lines represent the 90% confidence interval using Newey-West standard errors robust to heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation up to the third lag.

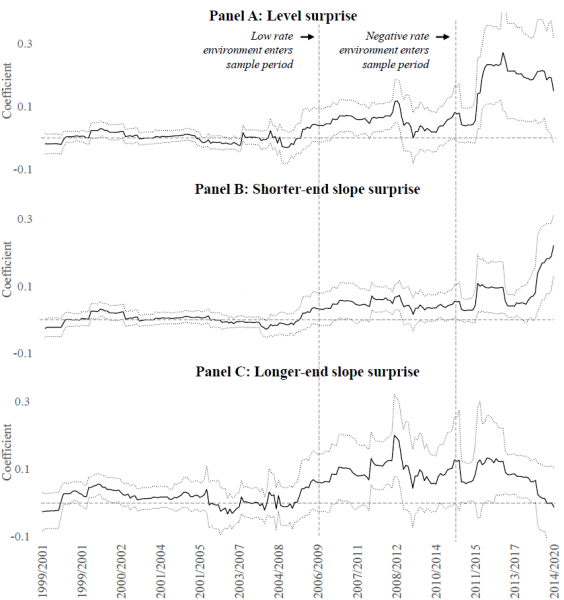

Our results show that banks face a disadvantage in comparison with other companies in times of negative interest rates. To evaluate whether this reflects the deposits channel of monetary policy, we analyze daily stock prices of individual banks and account for their relative dependence on customer deposit funding (Table 2).4 Monetary policy surprises are expected to have larger effects on stock prices of banks that are relatively dependent on deposit funding in times of negative interest rates. This is because the performance of these banks is likely to be more affected by changes to the deposit margin than the performance of banks with a relatively small share of deposit funding.

Table 2: SX7E banks and their average share of deposit and capital funding

Note: This table presents the average ratios of customer deposits to assets, and total and Tier 1 capital to risk-weighted assets of 24 European banks between 2014 and 2019. Together, these banks make up the European capita-lization-weighted bank stock index (SX7E) during the last years of the sample period (the index is reviewed periodi-cally). The deposit data include current accounts, demand deposits and time deposits from households and non-bank corporations. Interbank deposits are excluded. Data source: annual reports published by each individual bank.

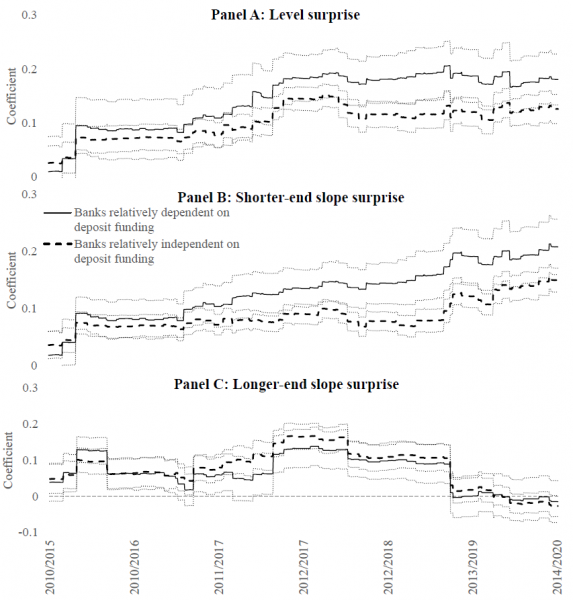

The results confirm that once the interest rate environment is negative, the effects on stock prices of a level and shorter-end slope surprise are larger for banks that are relatively dependent on deposit funding. In times of negative interest rates, a 10 basis points parallel shift in the yield curve and a flattening of the shorter-end of the yield curve reduce stock prices of deposit-dependent banks by around 2 percentage points (Figure 6, Panels A and B). Stock prices of banks relatively independent on deposit funding only drop by around half this amount. We also find that the effects are more persistent for banks that are relatively dependent on deposit funding. By contrast, the relative capitalization of banks is not found to influence the results. This suggests that in terms of bank performance, the deposits channel dominates the more traditional capital channel of monetary policy in times of negative interest rates. Further, longer-end slope surprises are not found to have different effects on the two types of banks’ stock prices in a negative interest rate environment (Figure 6, Panel C).

Figure 6: The varying effects of monetary policy on bank stock prices when rates are negative

Source: Bats et al. (2020)

Note: This figure shows rolling effects of yield curve surprises following ECB monetary policy announcements on stock prices of banks that are relatively dependent and independent on deposit funding. The estimations are run over fixed windows of 1461 observations, such that the last window covers the maximum period from the introduction of the ECB’s negative interest rate policy in June 2014 until the most recent available date in the sample. The dependent variable measures end-of-day movements in the log of individual bank stocks. End-of-day movements in the log of the broad stock market index (STOXX50) and (T)LTRO announcements are controlled for. The dotted lines represent the 90% confidence interval using robust standard errors clustered at the bank-level. See also the notes to Figure 5.

Should banks worry about negative interest rates? Most likely. A prolonged period of negative interest rates may be expected to hurt bank performance. In such an environment, banks make losses on retail deposit funding because the rates on these deposits are stuck at zero. This is consistent with the deposits channel of monetary policy. What reinforces this conclusion is that we find that banks that are relatively dependent on deposit funding suffer more, and more persistently, once interest rates turn negative. Indeed, negative rates have the largest impact on the performance of banks that are relatively dependent on deposit funding. This has implications for the real economy. When banks perform poorly, financial instability risks rise. Moreover, capital-constrained banks may reduce lending, which hampers the transmission of monetary policy stimulus.

But there is good news. The design of monetary policy can take into account bank performance when interest rates are negative. We show that distortions stemming from deposit rates bound at zero are lower when targeting the longer- rather than the shorter-end of the yield curve. Since retail deposits have a relatively short duration, deposit margins are not much affected by changing the longer-end of the yield curve. From this perspective, quantitative easing and yield curve control policies deserve special consideration when interest rates are negative and further monetary accommodation is called for.

Hoffmann et al. (2019) estimate the average duration of retail sight deposits at 2 years.

The data stem from the Euro Area Monetary Policy Event-Study Database by Altavilla et al. (2019).

While short-term interest rates have not been driven far in negative territory, the Bank of Japan has effectively steered the 10-year yield to flatten the longer-end of the curve. The Australian Reserve Bank has also undertaken YCC, albeit their intention was to reinforce the central bank’s forward guidance by targeting shorter-term interest rates.

The data on customer deposits include deposits from non-bank corporates. A caveat is that rates on deposits from non-bank corporates have to a small extent dropped below zero during the sample period, thus potentially preventing deposit margins turning negative in some occasions. While individual balance sheet data exist on the retail deposits of individual bank subsidiaries (e.g. the IBSI database by the ECB), these databases do not include data on all bank subsidiaries of the banking groups in the sample. Using this incomplete data would therefore generate identification issues; data on bank stock prices relate to each individual banking group on aggregate (i.e. including all subsidiaries). Given these complications, this paper uses customer deposits from households and non-bank corporations, recognizing this is an approximation of a bank’s relative dependence on retail deposits.