The issuance of securities by a central bank is a very market friendly instrument of open market operations, which already is used by many central banks all over the world. Now that the ECB faces the challenge of reducing bank liquidity with as little as possible disturbance of financial markets, it might also consider to issue ECB-securities. This would bring two advantages. First, it would be a much smoother way of reducing bank liquidity than the other option: reselling its portfolio of bonds acquired under the PSPP. Second, a sizeable issue of ECB-securities will create a deep and liquid market for EMU-wide common safe assets. The debt which is acquired by the ECB is de facto already mutualized, but would be transformed in new tradeable securities. Before starting, the ECB should of course do its homework, develop the necessary infrastructures and do more in-depth research into potential market disturbances. All in all, it seems to be worth investigating.

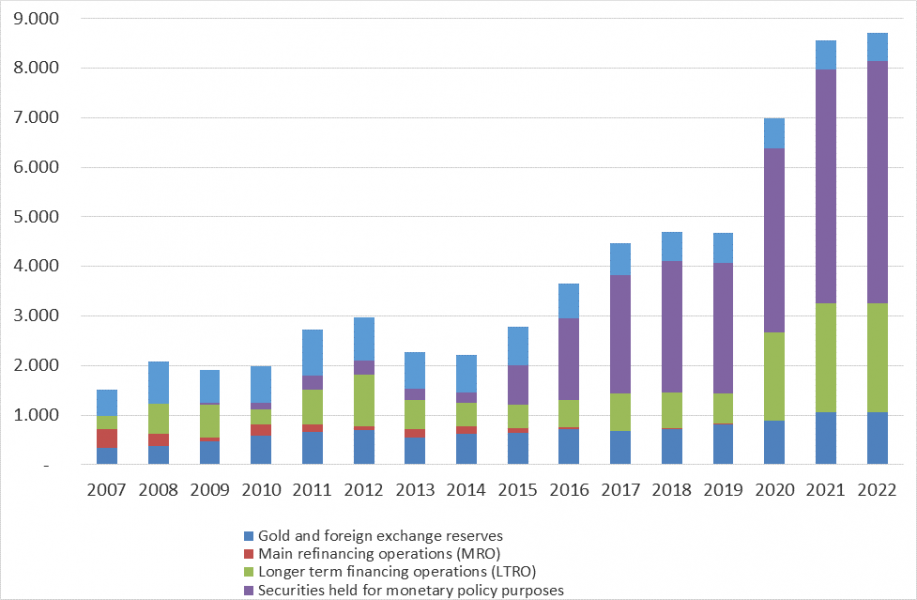

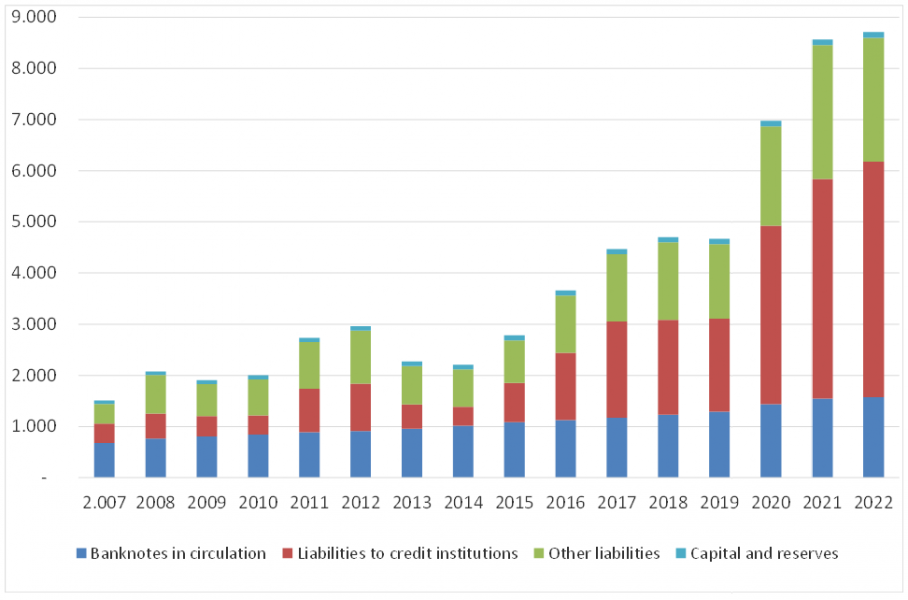

The unconventional monetary policies implemented during the last years have resulted in an enormous expansion of the balance sheet of the Eurosystem. Moreover, its composition also changed considerably. On the asset side, we find a large expansion in the items ‘lending to credit institutions’ and ‘securities held for monetary purposes’. The first entry reflects the targeted lending programmes, such as the TLTRO, under which the central bank has extended cheap funding to the banks in effort to stimulate their lending activity. In contrast, the so-called main refinancing operations (MRO), which used to be the dominant channel for open-market operations, have more or less disappeared. The second entry reflects its unconventional policies, viz. the purchase of large amounts of securities by the central banks (ECB and NCBs) under the various Asset Purchasing Programmes (APP and PEPP). On the liability side of the Eurosystem’s balance sheet we see a huge increase in commercial banks’ liquidity under the entry ‘liabilities to banking institutions’.

This situation raises several important policy questions. The first one is of course how to deal with the public debt that is acquired by the Eurosystem under the APP. This is a relevant question, as public debt acquired by the central bank has lost its monetary relevance. Moreover, it does not make sense to try to reduce public debt which is already owned by the central banks and thus ultimately its shareholders, viz. the governments (De Grauwe, 2021). In an earlier Policy Note, we have explained that the most practical way to deal with this part of the public debt is to keep it on the balance sheet of the central bank into infinity and base future fiscal policies on adjusted public debt ratios. Technically this is easy, but the real caveat here is of course how to prevent moral hazard (Boonstra, 2021).

In this Policy Note we will deal with the question how the central bank can reduce excess liquidity in the banking sector, preferably with as little market disruption as possible. This last precondition excludes rapidly selling large parts of its securities portfolio. First, of course, because selling public debt to the markets means a ‘demonetising’ of public debt, i.e. the notional amount of bonds that is available to market participants increases. That would certainly result in market turbulence, while at the same time it would bring an extra burden for fiscal policies of the member states. A more gradual, organic balance sheet runoff may perhaps be less disruptive but this would take many years if not decades, while today’s inflationary pressures could make reducing liquidity in the banking system more urgent. We argue that the ECB could solve this situation by the issuance of so-called ECB-bills. We will start by explaining the concept of central bank securities. Thereafter, we will discuss the special circumstances in which the ECB has to operate and the challenges it would face if it started to issue securities (ECB-bills). We will also illustrate that the issuance of ECB-bills could play a positive role in developing Europe’s capital market union and underpin the international position of the euro. Finally, we will offer some conclusions.

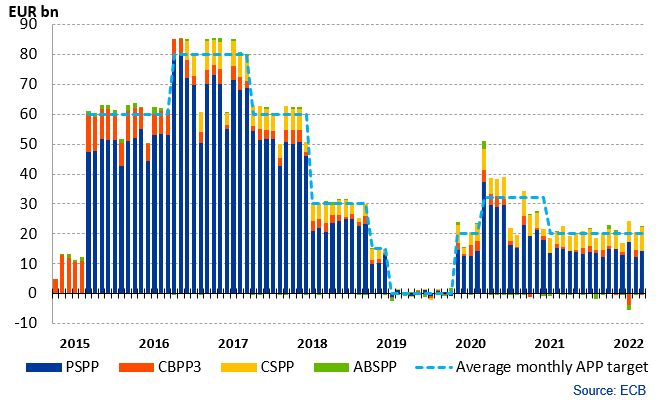

Since the outburst of the Great Financial Crisis in 2008, which in Europe was followed by the Eurocrisis, we have seen a drastic change in the ECB’s conduct of monetary policy. It started in 2008 with conventional measures, such as liquidity injections, but in unconventional amounts and against unconventional conditions (such as extended maturities under the so-called Long Term Refinancing Operations (LTRO), lighter collateral requirements and the switch to fixed rate, full allotment tender procedures). This was followed with more targeted interventions, aiming at supporting specific markets (such as the LTRO and SMP programmes), which in turn were followed by the PSPP, the CSPP, the ABSPP and the CBPP (together known as the Asset Purchase Programme or APP).1 These programmes are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Monthly purchases under APP

At the beginning of 2019, the Eurosystem (the European Central Bank (ECB) and the national central banks of the Eurozone countries) stopped its APP, only to restart it in November 2019 as the economy slowed, followed by the Pandemic Emergency Programme in reaction to the Covid crisis in 2020, under which since March 2020 around 1,700 billion of public sector bonds were acquired by the ECB.

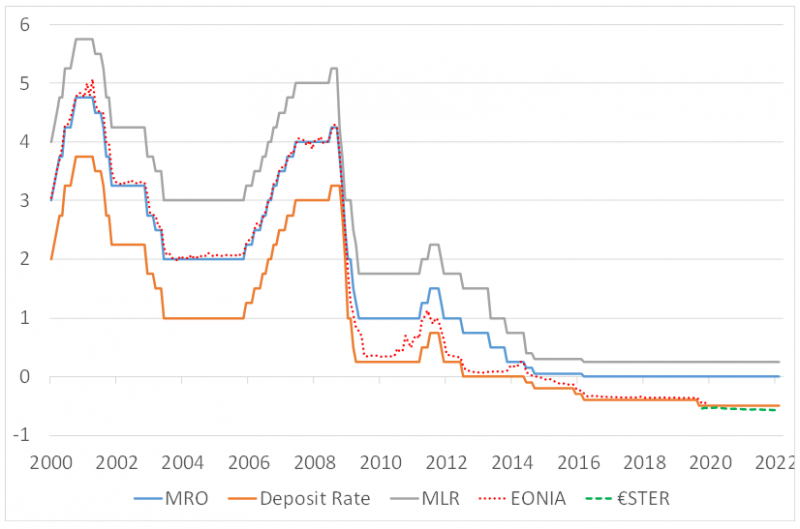

All these interventions were accompanied by a strong decrease in policy rates, to unconventionally low, viz. negative, levels (Figure 2).2 Although inflation remained low deep into 2021, toward the end of the year it started to increase. Initially, this was due to supply chain bottlenecks that manifested when the world economy started to grow again. More recently we see a strong increase in inflation, fuelled by spectacular higher energy prices and higher food prices, in reaction to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Although the underlying causes of the recent inflation are of a non-monetary character, it can’t be denied that current monetary conditions are very loose. This situation makes it urgent for central banks to act in order to prevent that high inflation expectations become sticky.

ECB in a unique position

The ECB was not unique with its unconventional measures. All major central banks have used large scale asset purchasing programmes when fighting the recession (Lane, 2022). But the environment in which the ECB operates is different from that of, for example, the Federal Reserve (Fed) or the Bank of England. If the Fed purchases government bonds or T-bills, it buys securities that are issued by its sovereign, the federal government of the United States of America. The ECB, however, has no single sovereign. It is the central bank of a currency area that has no traditional central government. When it intervenes in the bond markets, it buys debt issued by national authorities in the eurozone. This unavoidably has an impact on relative prices of the government bonds issued by its member states. Member states, whose governments often disagree on financial and economic matters. As a result, the ECBs interventions are politically more sensitive than that of other central banks.

Moreover, the fragmentation of EMUs public bond markets is often mentioned as one of the vulnerabilities of the Eurozone. Therefore, there has been a whole series of proposals to end this situation by the ‘mutualisation’ of public European debt (Muelbauer, 2013; ELEC, 2010, 2011),3 Under such proposals, the debt of individual countries is fully or partly combined by organizing a single European Public Debt Management Office and/or private parties that replace it by structured products. Moreover, there are other options to create a ‘common safe asset’ which do not by definition require mutualization of national public debt (Boonstra & Thomadakis, 2020). Although this discussion is far from concluded, for the time being no individual proposal can count on enough political support. However, a main exception is the issuance of so-called coronabonds in 2020. More recently there have also been proposals to finance certain strategic and urgent investments, such as energy transition and defence expenditures, with the issuance of bonds by the EU. This note will not further dwell on this discussion, but it remains to be remembered that the fragmented sovereign bond market is a structural weakness of the eurozone. Here, it is enough to make the point that the ECB operates in an environment that is relatively complex when compared to other central banks, that usually have a one-to-one relation with a national sovereign.4

The focus of the rest of this article is on the following questions: how can monetary conditions in EMU be normalized, which role can the issuance of securities by the European Central Bank play and could this have additional benefits for the stability of the Eurozone?

Between December 2014 and March 2022 the ECB5 purchased over €4,500 billion of public debt, asset backed securities, covered bonds and corporate debt. As a result, its balance sheet has grown from € 2,208 billion end 2014 to € 8,711 at end-March 2022. This is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The consolidated balance sheet 2007 – 2022 of the Eurosystem

| Assets (€ bn.) | Liabilities (€bn.) |

|

|

| Note: The data for 2022 are those of March 22th. Source: ECB | |

On the asset side of the ECB-balance, we find the securities bought by the Eurosystem. Today, it holds more than 40 percent of European public debt on its balance sheet. On the liability side we see a strong increase in the reserves that banks hold at the central bank. Today, the European banks are very liquid, as they hold much more reserves than they used to do before the crisis.6 The fact that in recent years the interbank overnight interest rate (EONIA/ESTER) which in the past used to follow the ECBs most important policy rate (the refi-rate), since 2013 is very close to or even below the ECBs deposit rate indicates over-liquidity in the banking system (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The ECB interest rate corridor and money market rates

Source: ECB

The strong increase of bank liquidity is not caused by the purchasing programmes alone. What can also be seen on the asset side of the ECB’s balance sheet is the strong increase of ‘Lending to credit institutions’. Under this entry, the liquidity operations of the central bank are booked, which until 2010 were dominated by the regular weekly open market operations, viz. Main Refinancing Operations (MRO). The interest rate on these transactions, the refi rate’, steered the money market rate. However, since the ECB strongly increased the size and broadened the scope of its Longer Term Operations (LTRO). Today, the MRO are only marginal phenomenon, as the lending to credit institutions is fully dominated by LTRO programmes. Interbank rates have dropped to the floor of the ECB’s interest rate corridor, the deposit rate, and the €STR even fixes below this level. For this article, it is relevant that the ECB can tighten money market conditions by gradually reducing its LTRO, without disturbing financial markets too much. The real challenge is of course how to reduce the bank liquidity that resulted from the APP.

As a result of the ECB’s purchase programmes, a substantial part of the public debt of the member states has been monetized. By monetizing we mean that these assets were bought by the ECB and replaced by very liquid assets, such as money or bank reserves. Under these purchasing programmes, government expenditure has effectively been financed by the Eurosystem, albeit ex post. Therefore, from an economic point of view this can be regarded as a form of monetary financing, which is strictly forbidden under the European Treaty (TFEU article 123). However, in the view of the ECB there are key differences with ‘normal’ monetary financing. The ECB has limited its interventions to the purchasing of existing debt in the secondary market, meaning that no new government spending was financed by ‘the money printing press’. From this point of view (and with a little fantasy), its actions can be perceived as a (very) large scale variety of a regular open-market operation. Secondly, its actions are meant to be temporary, although the time horizon of its interventions so far is not well-defined.

In the years ahead, the ECB is facing the challenge of normalizing its balance sheet and liquidity in the banking system. It can’t ignore the acute and steep inflation increases of end 2021 and especially early 2022. Of course, the central bank does not have the means to deal with cost-push inflation. But a credible reaction has become more urgent in order to prevent inflation expectations to increase. Whilst policy rates will be the first and foremost instrument through which tightening can be achieved, the large amount of excess liquidity will eventually come in focus as well. The question of course is whether it is possible to drain this liquidity without causing major market disruptions. As said earlier, it is hard to imagine that the ECB can simply sell 30 or even 40 percent of Europe’s public debt without causing an acute decline in bond prices and accompanying increases in yields, with of course spill-over effects to other securities markets.

The ECB itself is very well aware of this situation. It has no plans yet to actively sell securities to the market. Prior to the pandemic, it had chosen a very slow and careful, and thus time-consuming, path back to normalization. The bank took a first step, a gradual slowdown in the pace of the purchasing programmes, in 2018. The second step, a full stop of (net) new purchases, followed in January 2019. However, that lasted less than a year, before the economic outlook forced the ECB to reboot net purchases, albeit at a structurally lower pace. Then, the Covid crisis forced the ECB to scale up its purchases through the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) in early 2020. PEPP purchases have ended in March 2022, and net APP purchases will end later in the year. The next steps are still uncertain. The ECB has for the time being decided to keep its current portfolio intact by reinvesting the maturing bonds on its balance sheet. A first next step could be, of course, to stop reinvesting and let the portfolio gradually dwindle. This would lead to minimal market disruption, but it is a process that could take a decade or probably even longer.

A question that has not been asked so far is: does this situation also offer opportunities to strengthen the EMU and foster the international position of the euro? The answer is probably yes. We will discuss in the remainder of this Note why this may be the case.

The introduction of the euro in 1999, the creation of EMU, was a major step forward in the process of European integration. At the same time, it was also clear that EMU was a half-way house. Monetary integration preceded political integration. It is beyond the scope of this note, however, to dig deeply into the discussion about political integration, creation of a fiscal union (or not) or the importance of a central fiscal capacity at EMU level. Here, we will limit ourselves to two important themes, viz. the fragmentation of EMU’s government debt markets and, secondly, the euro’s handicaps by developing into a true world currency, that could rival the US dollar. Finally, after the crisis the ECB has become a middle-man, meaning that it has effectively killed the overnight money market. Transactions that used to run via the interbank money market are now conducted via the ECB. The issuance of ECB securities could help to restore the functioning of the money market as well.

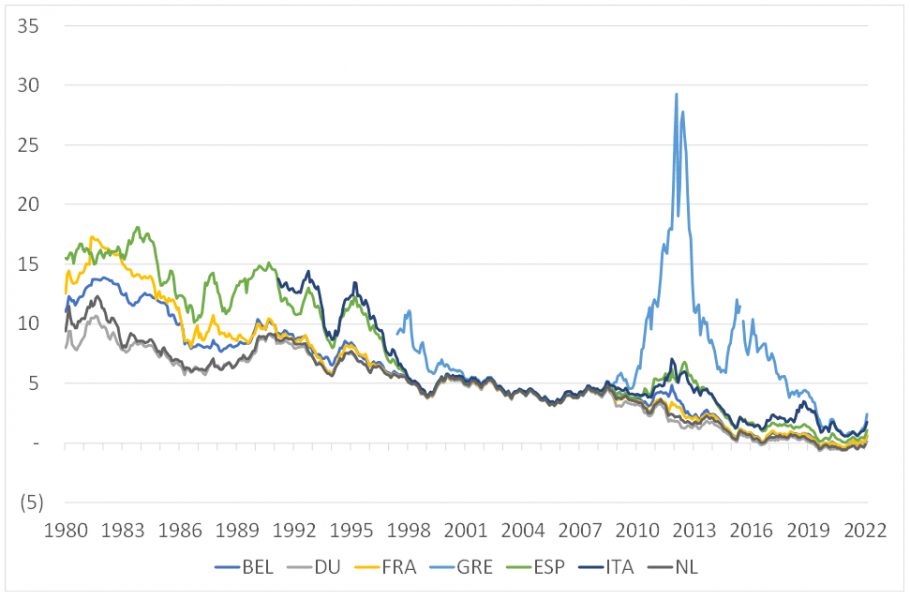

The Eurocrisis mercilessly exposed the weak spots of the Eurozone. The fragmentation of public bond markets along national lines offered speculators, in the absence of a well-developed market for EMU-wide common safe assets, the opportunity to put a crowbar in EMU, driving countries apart by increasing the spread between the financially stronger and the weaker countries. This is illustrated in Figure 4.7

Figure 4: Effective yield on EMU-government debt (%)

Source: OECD via FRED database

After 2008, the sharp increase in interest rate spreads on public debt within the Eurozone reflected relative performances of countries with respect to their public finances. Bond yields in financially weaker countries increased strongly, while stronger countries saw a substantial decline in bond yields. As a result the weaker countries faced a situation of low economic growth, high public deficits in combination with a public debt that was already too high and sharply increasing interest rates. This combination threatened to make their public debt unsustainable, and these countries were refused market access to finance their deficits at affordable interest rates. Initially, it was the Securities Markets Programme (SMP, 2010 – 2012) of the ECB that had to bail them out. After it appeared that the SMP was only partially successful, it was Draghi’s “whatever it takes” speech in July 2012 that changed the situation. Draghi suggested that the central bank was prepared to buy unlimited amounts of public debt of member states, which was later formalized under the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) programme. Only the threat to use OMT appeared to be enough to calm markets and bring interest rates in the periphery of the Eurozone down sharply. This period was the best illustration so far of the dangers of the fragmentation of public debt in Europe.8 This discussion is not new. Over time there have been many proposals to deal with this problem, but so far all of them have stranded on political unwillingness to tackle the problem (Boonstra, 1991, 2011, ELEC, 2010, 2011, Muelbauer, 2013). But it was only after the Eurosystem de facto mutualised European public debt by taking large chunks of it on its own balance, which drove bond yields lower, that the situation further improved and the Eurozone economy started to recover.9 The good news is that today’s situation, in which the ECB holds enormous amounts of public debt of EMU member states, also offers the opportunity to tackle the problem in a more structural way. Further good news is that this may be ‘sold’ as an unintended benefit of a regular monetary policy operation. The bad news, however, is that this nevertheless will likely hit a nerve with politicians. We will discuss this below.

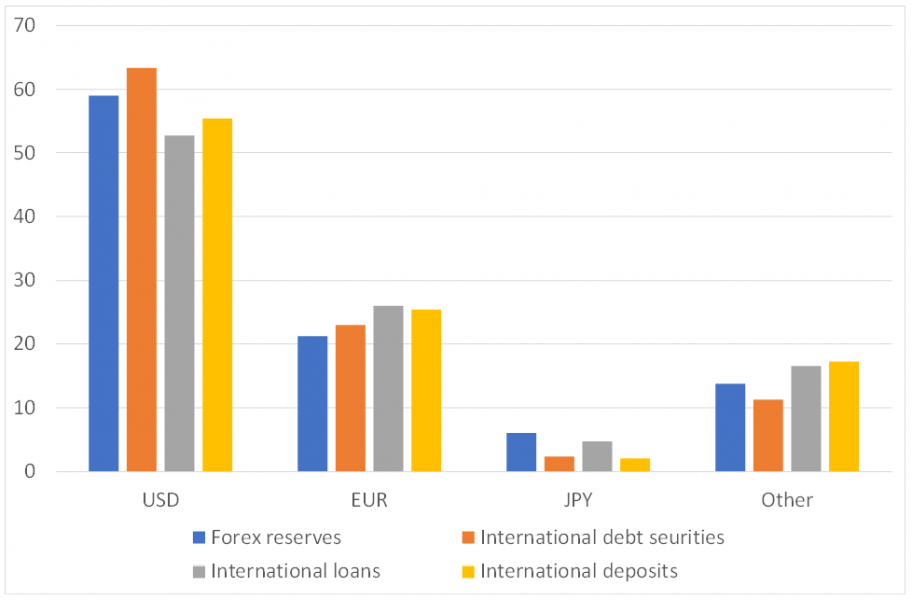

After the introduction of the euro on the financial markets in 1999 it immediately became the second most important currency of the world. It is a major reserve currency, investment currency, payment currency, anchor currency, vehicle currency and trading currency, much larger than other major currencies such as the Japanese yen, British pound, Swiss franc or Chinese renminbi. But, where many policymakers had hoped that the euro would challenge the dollar as the world’s leading currency, the importance of the euro remains relatively limited compared to its American counterpart. Its share as a reserve currency is more or less stagnant and its international use is mostly limited to European countries in the close proximity of the eurozone and in former colonies in Africa. The international use of the renminbi is increasing and this process may be expected to accelerate in the near future as China is far ahead with the introduction of a digital version of its currency, the renminbi, which also may be used for cross-border transactions (Boonstra, 2022).

Figure 5: The international position of the largest currencies

(market share (%), 2020)

Source: ECB

Since 2018, the EU has launched initiatives to further strengthen the international role of the euro (European Commission, 2018). As known, the dollar is the de facto anchor currency of the global monetary system. It is not a very good idea to strive after a situation in which the euro has this position. For the stability of the global monetary system it would not bring many advantages and, moreover, the anchor role brings disadvantages as well, which for the Eurozone might be relatively large (Boonstra, 2019a). That said, apart from this overambitious goal, it would be a good idea to strengthen the euro’s international standing, only to prevent that the euro will be overshadowed by the renminbi in the course of the next decade. However, here as well, the fragmentation of Europe’s bond markets is a major hindrance. There is no EMU-wide safe asset, so to say. Meanwhile, the demand for safe assets has only increased due to regulation. Were such an asset be available, this might be a great help. China, for example, has foreign currency reserves of over USD 3,000 billion. It would like to have a larger share of euro-denominated assets in its portfolio, but it is not very eager to invest in what it has once described as ‘bonds issued by European provinces’. A pan-EMU safe asset would potentially greatly improve the euro’s standing as a reserve currency.

As long as there is a relatively small amount of Eurobills or –bonds available compared to the supply of e.g. US Treasuries, securities issued by the ECB may play a positive role in tackling both issues mentioned here.

Central bank bonds are not really new. Although the world’s most prominent central banks, viz. the ECB and the Fed, currently do not use them, many other central banks are very active users of this instrument. Even the ECB briefly used them in its early years (1999 – 2003). However, the literature on this topic is rather limited and it is very difficult to have a complete list of central banks that use, of have used, this instrument.10 It appears, however, that it has been relatively popular by central banks in emerging economies. I will discuss this below. Between 2008 and 2012 the Swiss central bank (SNB) has also actively issued central bank bonds in order to mop up surplus liquidity in the money market.11

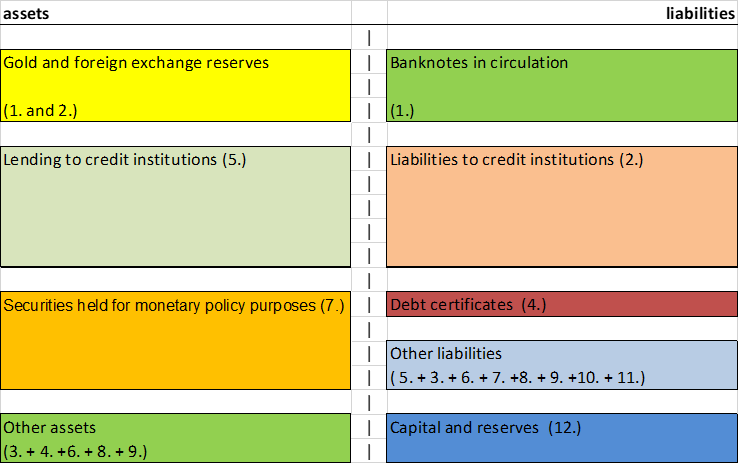

The balance of the central bank

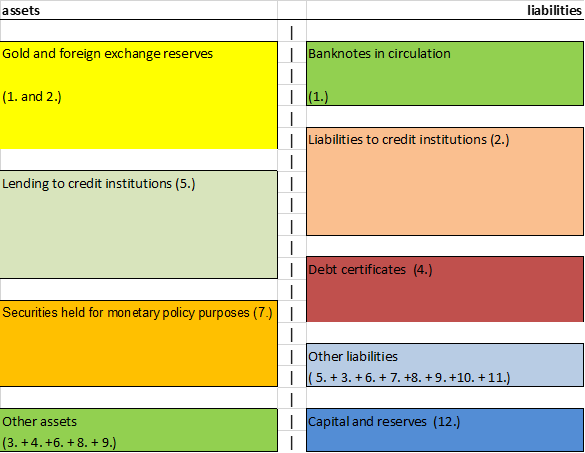

Let’s begin with a look at a stylized central bank balance (Figure 6).

Figure 6: A stylized ECB bank balance

Note: The figure concentrates on the balance sheet items that are relevant for this analysis. The rest is summarized under the label ‘other’. The numbers between brackets in the specific items correspond with the lemma’s used by the ECB.

The most important items on the liability side, at least in normal times, are the bank notes in circulation and the liabilities to credit institutions. This last item covers the money banks hold as liquidity reserves at the central bank. This reflects the role of the central bank as the creator of base money (M0), including its actions as lender of last resort. It contains the money banks hold on current accounts (under the reserve requirement), the deposit facility, and the liabilities that are the result of their repo-transactions and the fine-tuning operations. The item debt certificates is zero today, although the ECB used this instrument to a limited extent in the early years of its existence. Capital and reserves are present to cover losses.

On the asset side, the first items are the official reserves (gold and foreign exchange reserves). These are buffers to finance foreign exchange transactions. For major central banks, like the ECB, this post is relatively unimportant, as agents in major countries usually have access to market finance in any relevant foreign currency and, just as important, their currencies have a large degree of international acceptance. For developing countries with inconvertible currencies, this item usually is more important. There, the central bank is the ultimate guarantor if a country’s obligations in foreign currency.

The lending to euro area credit institutions is related to the conventional, regular monetary policy operations.12 The item securities held for monetary policy purposes reflect the financial assets required by the central bank under the unconventional interventions under the APP.

Liquidity scarcity versus surplus liquidity

Central banks prefer to operate in an environment of liquidity scarcity. In such an environment, banks are constantly in need of central bank liquidity, which the central bank can supply at will on its own conditions. The result is that the central bank has a very tight grip on both the interbank money market rate and the size of the monetary base. It also means that the growth of the balance sheet is driven by the demand for liquidity (liability-driven), while the growth of the asset side of the balance sheet follows. The moment a central bank starts to intervene in financial markets under one of the above mentioned special programmes, it is the asset side that dictates the rate of expansion of the balance sheet. In that case, the liability side follows and, if the purchasing of securities results in a strong increase of bank reserves, an oversupply of liquidity may be the result.13 One of the consequences of a such an oversupply is that the ECB has less grip on money market rates, which no longer follow the refi rate, but have dropped to, and in the case of €STR below, the floor created by the deposit rate (Figure 3).14 A further consequence is that banks, in case of a strong improvement of the economic climate, have more than enough liquidity to support a strong increase in lending. Probably even too much.

Dealing with surplus liquidity

If a central bank wants to regain its grip on the money market, it has several options to reduce the oversupply of liquidity. First, of course, it can wind down its LTRO lending to banks. Second, as explained, it can reverse its purchasing programme and start to sell securities on the market. Third, the central bank can try to decrease the degree of liquidity of the banks’ reserves by offering the banks term deposits with a longer maturity. This is what the ECB actually did in the past, although it stopped with this policy after 2013. And, as a fourth option, the central bank may start to issue central bank securities, so-called ECB bills.15 Like term deposits, this option would absorb liquidity. Moreover, it avoids one of the disadvantages of the former instrument: term deposits are not tradable, but bills are. Although holdings of central bank securities usually do not count as liquidity reserve, a bank or investor can always trade them on the open market. As a result, central bank securities reduce aggregate liquidity in the system, but individual holders can obtain liquidity by selling them to another investor. This in contrast to term deposits, which not only reduce liquidity but also flexibility. A further side-effect is, of course, that where access to the ECB’s open market operations and standing facilities is restricted to Eurozone banks, ECB-bills can also be bought by banks from outside the Eurozone, including other central banks, and by non-bank investors.16

Why should a central bank issue bills?

As explained above, the most important reason why many central banks start issuing bills is to reduce or prevent surplus liquidity. The background can be quite different.

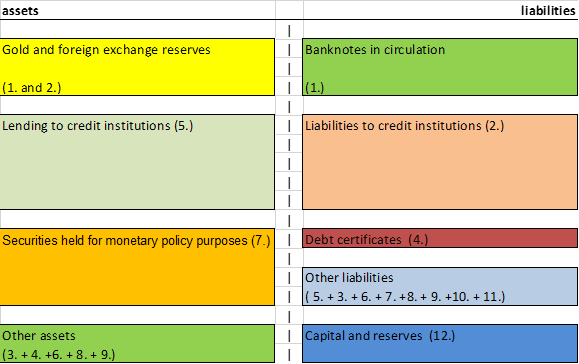

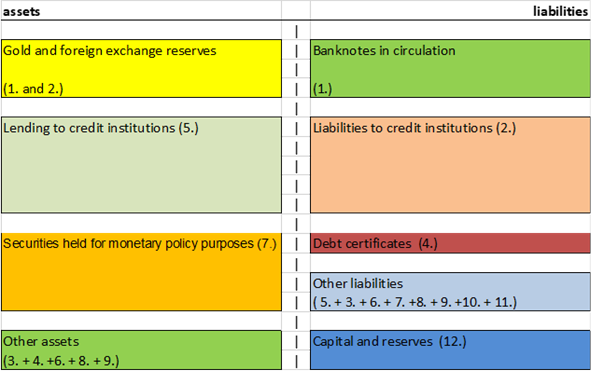

We will illustrate this with two stylized examples. In the first, a central bank wants to drain liquidity in order to prevent a strong appreciation of its currency. In emerging markets, for example, surplus liquidity can be the result of a massive inflow of foreign capital. If such an inflow is too large in the opinion of the central bank, it can intervene in the FX market by buying the foreign currency. The newly created liquidity can be drained with the issuance of central bank bills. This is reflected in Figure 7. The upper panel of this figure reflects the balance sheet prior to the capital inflow. The lower panel shows the new situation, meaning after the central bank has mopped up the liquidity that was caused by an inflow of foreign capital by issuing bills. All other items are being kept constant.

Figure 7: Bond issuance in reaction of capital inflows

Before capital inflow and bond issuance

After capital inflows and bond issuance

The lower panel of Figure 7 illustrates how the balance sheet of the central bank increases as result of the capital inflow. This is reflected in the increase of the gold and foreign exchange reserves (asset side). Without the intervention of the central bank, this would have resulted in an increase of the liquidity of the banking system (‘liabilities to credit institutions’). However, due to the issuing of central bank bills (liability side) the liquidity of the banking system is unchanged.

In a world of free-flowing capital, this situation is quite common in emerging markets. Therefore, several central banks in these countries are very regular issuers of central bank bills. But the SNB also acted this way from October 2008 to June 2012, when it intervened actively to prevent an unwanted appreciation of the Swiss Franc. However, this motive is less relevant for the ECB, as it does not pursue an exchange rate policy.

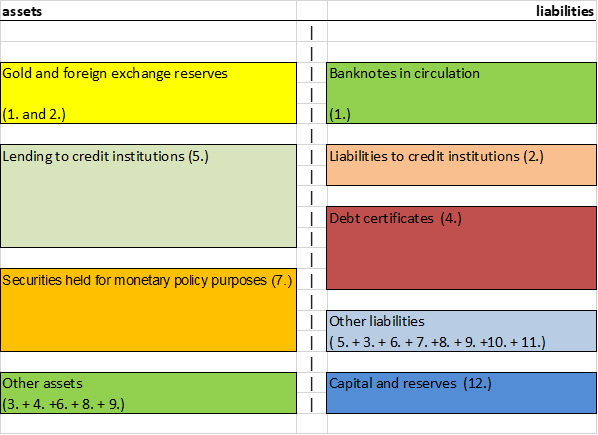

The second example, which better illustrates the ECB’s situation, is that of a central bank that wants to reduce bank liquidity without selling assets. Such a central bank can issue bonds and sell them to domestic banks. This would not shrink the central bank’s balance sheet but it does reduce banks’ excess reserves. That is offset by an identical increase in the amount of outstanding central bank bonds (substitution on the liability side of its balance sheet, see Figure 8). Again, the upper panel reflects the balance sheet prior to the issuance of securities, the lower panel the situation after the operation.

Figure 8: Reducing liquidity by bond issuance, keeping the balance sheet constant

Before bill issuance

After bill issuance

The lower panel of Figure 8 illustrates that the asset side of the balance sheet is unchanged, while the central bank intervention only results in substitution at the liability side of the balance sheet, where deposits of commercial banks at the central bank are replaced by the newly issued central bank bonds.

Market impact

From a market perspective the issuance of bonds by the central banks means that a new supply of high quality financial assets hits the market. It is important to have a closer look at the potential market impact.

Once the ECB would start to issue securities, so-called ECB-bills, this may have an impact on market rates. It is clear that some crowding-out effects are to be expected. However, compared to the effect of actively selling its securities portfolio the effect may be relatively limited.17 Mopping up bank liquidity through the issuance of ECB-bills can probably be effectuated in a shorter timespan than doing the same thing by selling the securities portfolio.18 The positive effect is that the ECB will improve its grip on the money market sooner than in other scenarios.19 We expect that if the ECB were to start start issuing ECB-bills, it use short maturities as a pilot programme. First, because this would be less politically sensitive. Secondly, because this gives the ECB better options to change or even stop the programme if unforeseen negative externalities would arise. Given this short maturity, certainly of the first issues of ECB-bills, the ECB retains all options available to keep market conditions in a tight grip. Moreover, the ECB can steer the process by targeting its initial issues explicitly towards banks, although other investors can acquire them on the secondary market. ECB bills may be a relatively attractive alternative to the deposit facility for Eurozone banks, provided that they offer sufficient yield pick-up. The enthusiasm for ECB-bills, which will most likely carry a zero-risk weighting, may be substantial. The next logical step for the ECB would then be to issue securities with longer maturities, if political conditions allow this. This would allow the ECB to lock up liquidity for a longer period without having to continually roll its tenders.

Additionally, it may also be expected that there will be new financial inflows from abroad as foreign investors, among which central banks that want to invest in ECB securities bills, being the first really EMU-wide safe asset with a substantial size. First of all, this would help boost the international role of the euro. Secondly, such demand from foreign investors may allow the ECB to drain liquidity more rapidly: it mitigates the price risks of new supply and therefore may lessen the potential side-effects of ECB issuance that we detail below.

Side effects

A first side effect could be that the euro’s importance as reserve currency may grow. This would be in line with the desire of the European Commission, that wants to increase the international role of the euro. A greater role as reserve currency may also help to develop other international roles, such as payment and investment currency.

A second, EMU-specific, effect would be that the de facto mutualisation of a part of EMU’s public debt may be continued for a longer time. This of course does only play in the Eurozone, the euro being the only major currency that is not backed by a single political entity. The political will to mutualize debt still remains low and large scale issuance of Eurobonds is not on the political agenda on this moment, although the NGEU bonds of 2021 were a watershed. Therefore, it may be clear that the issuance of ECB-bills with certainty will revive the political debate on the pros and cons of the mutualisation of public debt in the Eurozone.

At the same time the ECB’s actions have already resulted in a de facto mutualisation of public debt in the Eurozone, as a side-effect of its purchasing programmes. Without these actions, the euro may have fallen apart. If the ECB would continue this situation by not selling its portfolio, but by financing it with the issue of ECB-bonds, this mutualisation would be made more or less permanent, but would not lead to more mutualisation than already is the case today.

Of course, today all EMU member states are shareholder of the European Central Bank, which means that they together guarantee potential credit losses on its portfolio. It is important that this is only the case for the part of the portfolio of the Eurosystem that is directly held by the central bank itself. The overwhelming part, over 80% of the total, was purchased by the NCBs who, as a deviation from the rule, carry the risk on their own portfolio of (national) government bonds. The result is that the initial amount of bills that the ECB could issue would be limited to 20% of the public debt that the Eurosystem has acquired under the APP and PEPP. In the longer run, reversing the monetary effects of quantitative easing will probably require more liquidity absorption. The issuance of ECB securities is not limited to the risk-shared part of the portfolio holdings. In fact, the ECB can issue securities regardless whether it has a QE portfolio or not. However, if issuance volumes eventually exceed the amount of assets purchased under full risk sharing, this could lead to renewed questions about de facto debt mutualisation.

Thirdly, ECB-bills may compete with other public debt. The arrival of a new, large issuer of a AAA-rated EMU-wide safe assets will certainly have impact on market conditions. ECB-bills may affect the interest rates that other AAA-issuers have to pay on their national public debt. To be specific: they may directly compete with Bunds and Dutch State Loans (DSLs). It will also crowd out lower-rated public debt, such as Italian, Spanish or Portuguese government bonds, which may have to offer higher yields.20 However, we expect these distortions to be smaller than a scenario in which the ECB actively reduces its holdings of public debt. Moreover, any price effect may be mitigated by the extra inflow of money from foreign investors that are attracted by the new instrument. As the ECB initially should tread very cautiously, especially in the early stage when the market (and political) reaction is the most uncertain, we expect it to limit itself to short maturities when it starts its issuance programme. Ideally, of course it should aim to issue longer bonds as well in the future in order to establish a full yield curve with benchmark issues.

Although the instrument is currently not being used by the ECB, bond issuance by central banks is an instrument that is well-tested by several other central banks in both industrial and emerging economies. It brings several potential advantages, the most important being the possibility to reduce the supply of liquidity in the money market in a relatively short time span. For EMU, it may bring additional positive effects, such as an increase in the role of the euro as a reserve currency and a continuation of the de facto mutualisation of national public debt by the ECB. Especially when the ECB would over time broaden the mix of tenors it issues, this would greatly help to establish an EMU-wide safe asset as a benchmark, which would have a major positive contribution towards the creation of EMUs capital market union. Of course, the issuance of (conditional) Eurobonds could have the same effect, without the negative impact on the prices of national public debt, as under a Eurobond programme these would be replaced by the new instrument (Boonstra, 2013, Muelbauer, 2013). But in today’s situation, Eurobonds issuance is not on the political agenda, although there are alternative initiatives around to create pan-EMU safe assets. At the same time, it is clear that it does not make sense that the ECB, after saving the Eurozone with its interventions, which as a side-effect resulted in a partial mutualisation of Eurozone debt, should gradually reverse its actions. This would automatically end in demutualisation of debt and reinserting the fragilities in the Eurozone that it had to combat in the first place.

Given this background, it would be a good thing to have a closer look at the potential of the issuance of securities by the ECB. The pool of securities which is held by the central bank itself is large enough for a serious experiment. Initially, the ECB may limit the experiment to short maturities, maximum one year or even shorter, in order to minimize disturbances in the bond markets. This would bring all kinds of possibilities for learning along the way or, if necessary, even to stop the issuance programme within a short time span. In the longer term, one can image that ECB issues a series of securities, which maturities that or less matches the redemption schedule of its securities portfolio. But before starting, the ECB should do its homework, develop the necessary infrastructures, do more in-depth research into potential market disturbances and, if possible, create political backing for the use of central bank bond issuance. But all in all, it seems to be worth investigating.

Boonstra, W.W. (1991), The EMU and national autonomy on budget issues: an alternative to the Delors and the free market approaches, in: R. O’Brien & S. Hewin (eds.) Finance and the International Economy: 4, Oxford University Press/American Express, 1990, pp. 209 – 224.

Boonstra, W.W. (2019a), The global economy needs a new currency anchor, Rabobank Special, 3 January, 2019.

Boonstra, W.W. (2021), How to prevent a too restrictive fiscal policy in Europe?, SUERF Policy Note No 239.

Boonstra, W.W. (2013), Some Thoughts on Euro T-Bills, Rabobank Special, 29 October 2013.

Boonstra, W.W. & A. Thomadakis (2020), Creating a common safe asset without Eurobonds, ECMI Policy Brief No 29, CEPS/ECMI, December 2020.

European Commission (2018), Towards a stronger international role of the euro, Communication from the commission, 5 December 2018.

European League for Economic Cooperation (ELEC, 2010), The creation of a common European bond market, Cahier Comte Boël No. 14, Brussels, March 2010.

European League for Economic Cooperation (ELEC, 2011), An EMU Bond Fund Proposal, Brussels, November 2011.

Grauwe, P. de (2021), Debt cancellation by the ECB: does it make a difference?, SUERF Policy Brief No. 55, March 2021.

Gray, S. & R. Pongsaparn (2015), Issuance of Central Bank Securities: International Experiences and Guidelines, Working Paper WP/15/106, International Monetary Fund, May 2015.

Hardy, D.C. (2020), ECB Debt Certificates. The European counterpart to US T-bills, Department of Economics Discussion Paper Series, No 913, Oxford University Press, July 2020.

Hartmann, P. & F. Smets (2018), The First twenty Years of the European Central Bank: Monetary Policy, ECB Working Paper No. 2219, December 2018.

Lane, P.R. (2022), Monetary policy during the pandemic: the role of the PEPP, Speech at the International Macroeconomics Chair Banque de France – Paris School of Economics, Paris, March 31, 2022.

Muelbauer, J. (2013), Conditional Eurobonds and The Eurozone Sovereign Debt Crisis, Discussion Paper Number 681, Oxford University, December 2013.

Rule, G. (2011), Issuing Central Bank Securities, Centre for Central Banking Studies, Bank of England.

Public Sector Purchasing Programme (PSPP), Corporate Sector Purchasing Programme (CSPP), Asset-Backed Securities Purchasing Programme (ABSPP) and Third Covered Bond Purchasing Programme (CBPP3).

Hartmann & Smets (2018) offer a rich overview of the ECBs monetary policy over time, including a detailed description of all its unconventional programmes. Lane (2022) discusses the recent policy measures of the ECB in reaction to the Covid pandemic.

When we use the expression ‘mutualisation’ in this text, we mean the process in which public debt of individual countries is combined in order to create a pan-national issuance of public debt.

A further special feature of the situation under which the ECB has to conduct its policy is the prohibition of monetary financing of public expenditure. In the US and the UK, an expansive monetary policy was initially complemented by expansive fiscal policies. In EMU, however, fiscal policies after the crisis in almost all member states were very restrictive.

Throughout this note we will use the term ECB as equivalent of the Eurosystem, although this is technically not correct. However, this is justified by the fact that all decisions of the Eurosystem are made by the ECB-board. It is important to note that due to the Eurosystem’s decentralized structure, the actual operations are conducted by the national central banks. As a result, much of the purchased securities are actually on the balance sheet of the national central banks. Note, that the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) is distinct from the Eurosystem and also includes non-EMU central banks.

And actual bank reserves are much higher than required reserves (1 percent of the deposit base).

In the years before the crisis the financially weaker countries enjoyed very low interest rates on their public debt that in general did not reflect the relatively poor quality of their public finances. Most of them did not use this windfall ‘gain’ since the start of EMU to consolidate their public finances.

The discussion about the pros and cons of mutualisation of public debt is beyond the scope of this note. A wrong design of so-called Eurobonds or –bills may fuel moral hazard which may seriously undermine fiscal discipline, whereas on the other hand well-designed conditional Eurobonds may stimulate responsible fiscal policies. See Muelbauer (2013) for a thorough discussion of this topic.

Note that only a limited percentage of the purchased assets is acquired under full risk sharing. A large part (80%) is on the balance (and for the risk) of the National Central Banks (NCBs), and thus not mutualised. So the ECB itself owns less than 20 percent of these assets. Which is still a sizeable € 400 billion of securities.

Gray and Pongsaparn (2015) indicate that over 30% of central banks issue or have issued central bank securities. Among them are Chili, Thailand, Korea, Switzerland and Japan. A thorough discussion of the topic can be found in Hardy (2020).

This item has two sub-items: the securities received as collateral under the main refinancing operations and securities received as collateral under the long-term refinancing operations.

Therefore, the ECB originally sterilised its purchases under the Securities Markets Programme by conducting liquidity absorbing operations.

Which of course means that the ECB can still increase €STR by raising the deposit rate.

We use the term ECB bills, to illustrate the fact that we expect that the securities issued by the central bank may initially have relatively short maturities.

Currently only Eurozone banks have access to the deposit facility, which in an environment of liquidity abundance leads to short-term money market trades between a bank and a non-bank counterparty being conducted at rates below the deposit facility, as illustrated by the level of €STR fixings.

Especially if one assumes that the ECB would continue to observe the capital key when selling the accumulated portfolio.

The ECB has to develop an infrastructure to issue its own securities, which may take time. However, it has used the instrument briefly before, in the early years of the Eurozone. Moreover, it can possibly draw on the experience of the SNB, which has used this instrument more recently.

This assumes that the ECB ultimately would like to return to a situation with little to no excess liquidity, which would return money market rates to the middle of the policy rate corridor and restore the weekly refinancing as the main policy instrument and the MRO rate as the key policy rate.

In South Korea, where is a decade-long experience in simultaneously issuing central bank and government bonds, they coordinate the issue calendars of the government and the central bank. (Gray & Pongsaparn, 2015). In EMU this option is not available, as there is already a large number of issuer action over the full length of the yield curve.