This Policy Brief provides a summary of Adalid et al. (2022) and is published simultaneously by Central Banking. It should not be reported as representing the views of the European Central Bank (ECB) or the Eurosystem. Gabriela Silova worked on this paper while employed by the ECB and has in the meantime left the ECB and joined Morgan Stanley. Morgan Stanley disclaimer: “This paper was written in Gabriela Silova’s individual capacity and is not related to her role at Morgan Stanley. The analysis, content and conclusions set forth in this paper are those of the authors alone and not of Morgan Stanley or any of its affiliate companies. The authors alone are responsible for the content.” Carolina López-Quiles worked on this paper while employed by the ECB and has in the meantime left the ECB and joined the IMF. IMF disclaimer: “The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Monetary Fund, its Management, or its Executive Directors.”

In 2021 the Eurosystem launched the investigation phase of the digital euro project, which aims to provide euro area citizens with access to central bank money in an increasingly digitalised world. While a digital euro could offer a wide range of benefits, it could also alter the transmission of monetary policy and impact financial stability through changes in the demand for bank deposits and services from private financial entities. Acknowledging the significant uncertainty surrounding the design of a potential digital euro, potential demand for it and the prevailing environment in which it would be introduced, this SUERF policy note presents a set of analytical exercises that offer insights into the consequences a digital euro could have for bank intermediation in the euro area. Based on assumptions about the degree of substitution between different forms of money in normal times, several take-up scenarios are used to explore the mechanisms through which commercial banks and the central bank could react to the introduction of a digital euro. Overall, effects on bank intermediation are found to vary across credit institutions in normal times and to be potentially larger in stressed times. Further, the analysis finds that in principle factors such as CBDC remuneration and usage limits could be deployed to manage the impacts on bank disintermediation.

The implications of introducing a digital euro for bank intermediation will depend heavily on the size of the take-up. However, estimating the future demand for a digital euro is particularly challenging at this stage given (i) the lack of experience with CBDC, particularly in advanced economies, (ii) that many important design features of a potential digital euro have not been decided yet and (iii) the uncertainty surrounding the prevailing financial and monetary environment at the time of introduction.

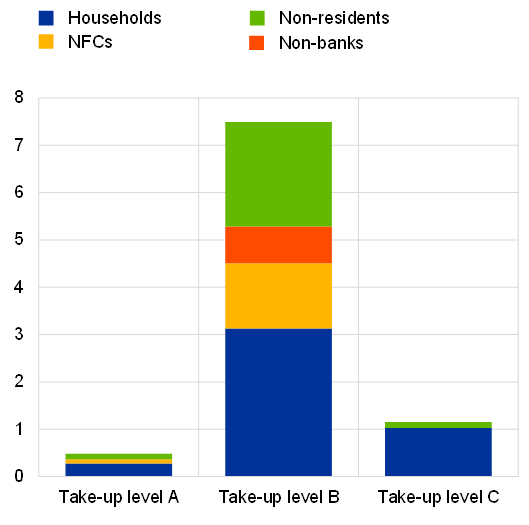

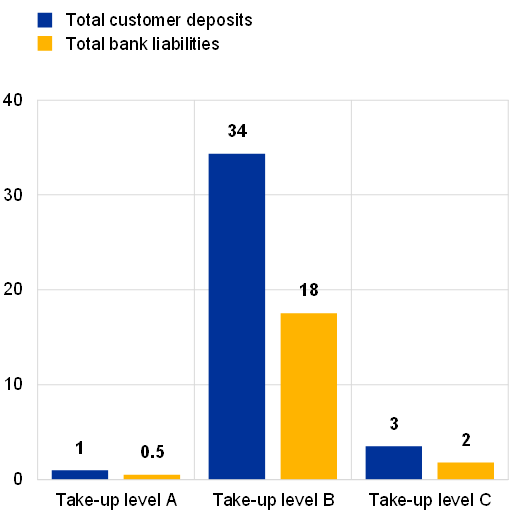

Therefore, we focus on two hypothetical scenarios that illustrate markedly different take-up levels, complemented by one in which the supply of digital euro is restricted. The choice of these scenarios is not based on their likelihood and, thus, should not be seen as an attempt to forecast future demand for a digital euro. They merely aim to numerically illustrate three different cases: a “moderate demand for retail payments only” (Take-up A), a “large demand” both for retail payments and storage of value (Take-up B) and a “capped” take-up (Take up C, see Chart 1.a).2 These static take-up estimates would represent between 0.5% and 18% of euro area bank liabilities (Chart 1.b). However, they do not take into account potential reactions of banks (e.g. banks could change the conditions and functionalities of the services they offer to defend their market share) or general equilibrium effects, including any potential reaction by the central bank aiming to offset unwanted effects.

Chart 1

Hypothetical digital euro demand scenarios

| a) Digital euro take-ups by sector (EUR trillions) |

b) Digital euro take-ups as a share of bank liabilities (percentages) |

|

|

Source: ECB calculations.

Note: The chart on the right shows what proportion of the total take-up in the chart on the left substitutes banknotes or overnight deposits. Total customer deposits includes all deposit liabilities except those between euro area banks.

Balance sheet relations provide a consistent framework to analyse how the introduction of a digital euro would alter banks’ balance sheet positions and affect banks’ intermediation capacity.

To meet their clients’ demand for CBDC, banks must obtain the necessary reserves and can undergo five possible adjustment channels. In resemblance to banknotes, it is assumed that banks would be the distributing agents of a digital euro. When their clients want to replace deposits with CBDC, banks must first obtain the digital euro from the Eurosystem (in exchange for reserves or banknotes) and then “resell” it to the final holders. To this end, banks can (I) intermediate the substitution of banknotes for CBDC on behalf of their clients, with no impact on their balance sheets; (II) draw down existing reserves with the Eurosystem, potentially leading to a reallocation of reserves through inter-bank borrowing; (III) increase their borrowing from the Eurosystem; (IV.a) sell assets to the Eurosystem from their own portfolios; (IV.b) sell assets to the Eurosystem on behalf of their clients. In this case, the volume of deposits in the economy would remain unchanged, as banks would credit the accounts of the sellers, thus offsetting the deposit substitution into CBDC. Which of these adjustment channel/s will be used depends on the preferences and constraints of banks, customers and – importantly – on the decisions of the Eurosystem to accommodate the adjustments on its own balance sheet resulting from CBDC issuance.

When evaluating the impact on bank intermediation capacity, the interplay between a digital euro and the frictions and constraints present in the financial system needs to be assessed. The stylised balance sheet analysis corroborates results in the literature that in a completely frictionless economy, the introduction of a digital euro would be neutral for banks’ intermediation capacity.3 However, frictions and regulatory constraints are pervasive in the current financial system and are likely to change this outcome. For instance, with an imperfect money market, a significant reduction in banks’ reserves with the central bank may result in money market tensions. Similarly, an imperfect substitutability between deposits and central bank funding (e.g. because of collateral requirements, or stigma associated with excessive reliance on central bank funding) might affect bank credit provision.

To meet customer demand for CBDC, individual banks face a trade-off between balancing their profitability and liquidity risks. To exchange retail deposits with CBDC, a bank can either use its own reserves or acquire new reserves via central bank funding, or market funding. When choosing between different funding options, a bank faces a trade-off: Secured funding is generally cheaper than unsecured funding and short-term funding is cheaper than long-term funding. However, using its own reserves or obtaining funding secured by high quality liquid assets (HQLA) negatively impacts banks’ liquidity positions. Drawing down or encumbering its stock of HQLA depletes the pool of assets that can be liquidated in times of need. Furthermore, using short- rather than long-term funding increases roll-over risk in times of stress.4

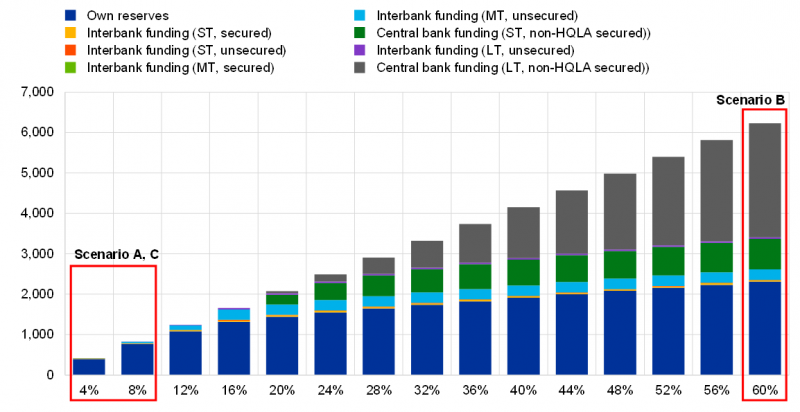

If a digital euro was introduced in the presence of such high reserves, most banks could accommodate CBDC demand as anticipated in scenarios A and C using their excess reserves, under assumed liquidity preferences.5 A bank balance sheet simulation model suggests that most banks could accommodate CBDC demand using their excess reserves with low CBDC demand (see Chart 2). However, bank-level heterogeneity with respect to liquidity preferences and reserve and collateral availability could result in diverging bank responses to the introduction of CBDC. Furthermore, liquidity regulation or voluntary liquidity buffers could reduce the total amount of reserves that banks are willing to use or sell to facilitate CBDC conversion. Thus, the central bank might want to provide non-HQLA long-term lending (>1 year) or non-HQLA purchases to accommodate CBDC demand, especially for the high-demand scenario B.

Chart 2

Bank balance sheet re-optimisation

(x-axis: share of deposit outflow covered by funding sources; y-axis: EUR billions)

Source: Own calculations from simulation using regulatory data.

Notes: The simulation uses data from Q3 2021 for a selection of SIs and LSIs.

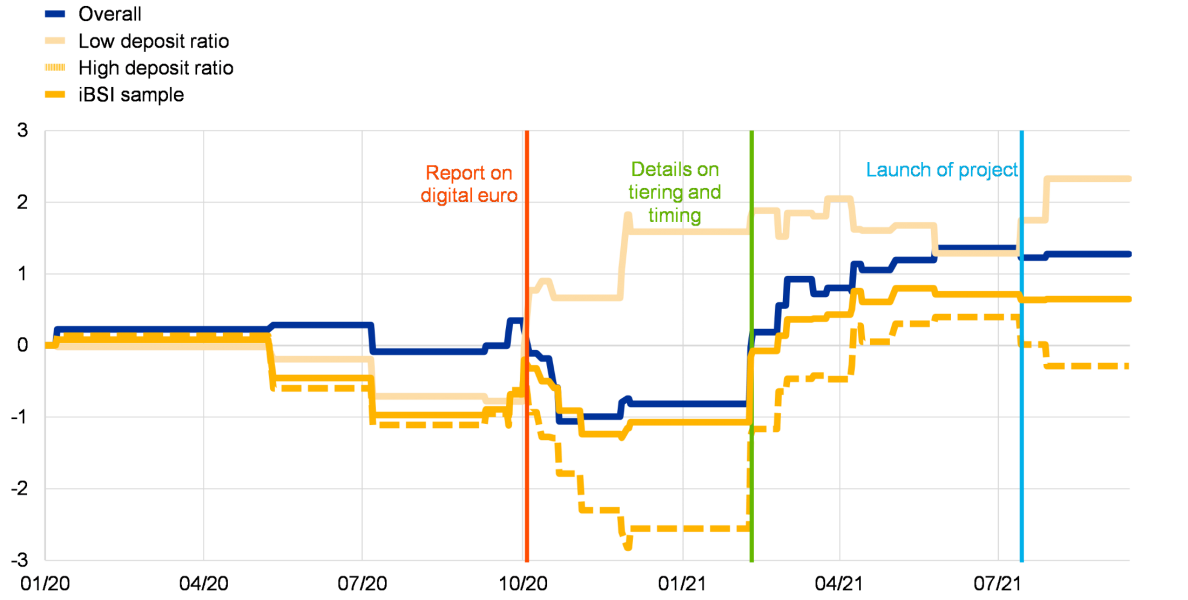

Bank stock market valuations provide some insight about current investor perceptions regarding the potential implications of a digital euro for banks’ business models. This information can be extracted around events that define agents’ expectations about the digital euro, to the extent that banks’ stock prices reflect also future profitability prospects. In fact, stock market developments might be one of the few, however partial, sources of evidence available given that the digital euro project is currently still under development.

News about the digital euro have had a stronger, albeit temporary, impact on valuations for banks relying more on deposit funding (Chart 3).6 Following the publication of the ECB report on the digital euro in early October 2020, stock prices of banks more reliant on deposit funding declined but fully recovered as more details about the actual design and timing of the project were made public (dashed dark-yellow line in Chart 3).7 This reaction is consistent with market participants either discounting a potentially large disintermediation effect or needing several months to absorb the information flow on this subject. At the same time, stock prices of banks with low reliance on deposits increased in response to digital euro events ever since the publication of the ECB report in October 2020 (solid light-yellow line in Chart 3). This seems to be in line with the business models of these banks being perceived by markets as being less affected by the introduction of a digital euro, while still having the potential to benefit from the possible new business opportunities created.

The evolution of valuations seems to point to investors anticipating diverging, but transitory, implications for lending conditions across bank business models. The reallocation in market shares that the differentiated impact across more and less deposit-reliant banks might entail (difference between the solid light yellow and dashed dark yellow lines of Chart 3) can be quantified by studying the reaction of banks themselves in the months spanning the events referred to above. Looking at developments in loan markets8, the cross-sectional difference in the reaction of stock prices to digital euro news (amounting to roughly 4 percentage points) has been associated with a reallocation of market shares of around 1.5% of ex ante volumes at the peak. This reallocation was, in fact, temporary and limited to the period leading up to the communication of further details about the project.

Chart 3

Stock market reactions to CBDC news by euro area banks

(percentage points)

Source: Burlon, Montes-Galdón, Muñoz and Smets (2022). Notes: A 3-factor Fama-French model is fitted to daily two-day stock market returns of 134 euro area banks, isolating the abnormal returns occurred at key events for each bank. Each horizontal segment reports the cumulated abnormal returns across key events. The solid dark yellow line focuses on the IBSI sample, with dashed dark-yellow and solid light-yellow lines reporting the detail by level of deposit ratio, above and below median respectively. The three vertical lines indicate three key noteworthy events: the publication of the ECB report on the digital euro on 2 October 2020, the speech by Mr Panetta on 10 February 2021 (Panetta, 2021b) and the launch of the digital euro project on 14 July 2021. Latest observation: 10 September 2021.

Besides any implications for bank intermediation in normal times, a digital euro could affect the severity of bank runs as it would provide citizens with a super-safe asset at comparatively low storage costs. During times of stress and depending on its design, the role a digital euro could potentially play as a store of value could become particularly relevant as it is a more easily accessible super-safe asset with lower storage costs, when compared to cash.9

Using a model for simulated bank runs that approximates the speed and scale of past economy-wide bank runs we assess potential effects of the presence of a CBDC. The model assumes that individual decisions on the conversion of bank deposits into cash or CBDC are based on an expected return maximisation behaviour. Cash and CBDC are the only assets that can be used as a safe store of value with the latter being preferred due to a technological superiority.10 The dynamics of monthly deposit withdrawals are simulated, and the parameters of the model are calibrated such that simulated withdrawals match the deposit outflows registered during the recent economy-wide bank runs in Greece (2015) and Cyprus (2013).

Counterfactual simulations that vary the limits on CBDC usage and remuneration are used to describe the potential impact of a digital euro on the severity of bank runs. The presence of a digital euro may affect the scale and speed of bank runs along three dimensions. First, depending on its remuneration and usage costs, a digital euro may allow for a lower- cost alternative to cash holdings. Second, depending on the selection and calibration of usage limits it may also allow for instant and “unlimited” withdrawals (whereas the conversion of deposits into cash is subject to limits). Third, the scale of a bank run decreases with the amount of deposits that has been converted into a digital euro in normal times (i.e., prior to the bank run). This is the case because the scale of a bank run is increasing in the amount of deposits in the system that can be withdrawn.

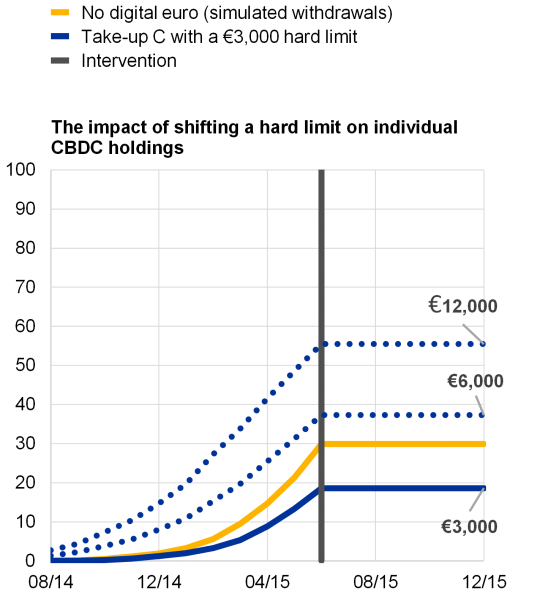

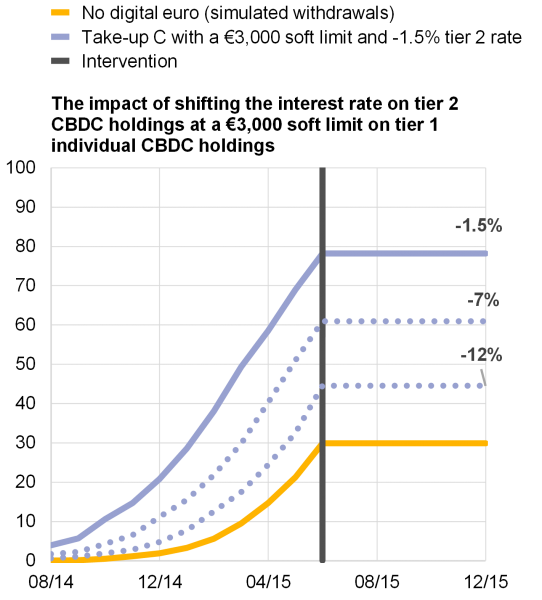

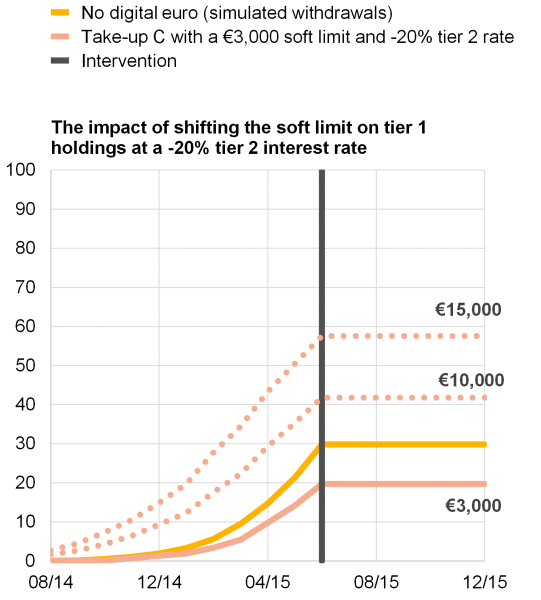

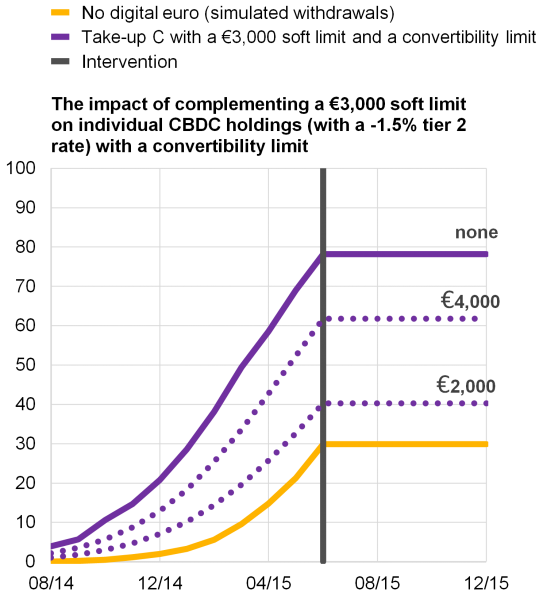

If adequately calibrated, CBDC usage limits and remuneration can neutralize any effect the presence of a digital euro could possibly have on the scale and speed of bank runs. If demand were unconstrained, a digital euro would lead to an increase in the scale and speed of a (simulated) system-wide bank run. However, and depending on their calibration, there are different types of usage limits that could permit a digital euro not to amplify the scale and speed of simulated economy-wide bank runs (Chart 4). When compared to a scenario without a digital euro, the increased scale of bank runs is reflected by a larger share of deposit withdrawals, while the increased speed of bank runs is reflected by the shorter time it takes to reach a certain amount of deposit withdrawals. The potential costs to society of this increased scale and speed of simulated bank runs would need to be weighted with potential benefits that are not considered in the analysis but some of which the paper cites.

Chart 4

Simulated cumulative deposit withdrawals in Greece under illustrative digital euro take-up scenario C: Hard vs soft limits on individual digital euro holdings

| a) Hard limit on individual CBDC holdings | b) Soft limit on individual CBDC holdings (I) |

| (Aug 2014 – Dec 2015, percentages of deposits in Aug 2014) | (Aug 2014 – Dec 2015, percentages of deposits in Aug 2014) |

|

|

| c) A soft limit on individual CBDC holdings (II) | d) A soft limit on individual CBDC holdings (III) |

| (Aug 2014 – Dec 2015, percentages of deposits in Aug 2014) | (Aug 2014 – Dec 2015, percentages of deposits in Aug 2014) |

|

|

Source: Own calculations from simulation using BSI data

The study is complemented with a theoretical model for bank run analysis which concludes that introducing a CBDC induces efficiency gains but may also increase the probability of cyclical deposit withdrawals.11 Due to the superiority of CBDC as a storage technology – which in the model is captured by the empirically-relevant assumption that cash holdings are subject to storage costs – any replacement of cash with CBDC implies that individuals need less resources to satisfy their demand for central bank money as a safe store of value. Consequently, such substitution allows for an increase in deposit holdings (i.e., structural bank intermediation). According to this model, the scale of a bank run only depends on depositors’ beliefs of what other depositors will do and is independent from the introduction and availability of a CBDC. Nonetheless, it shows that under certain conditions the introduction of a CBDC increases the probability of state-dependent conversions of deposits into central bank money.

A digital euro would offer several economic benefits but, depending on its design, it could also affect financial stability and monetary policy transmission through changes in the demand for bank deposits. Due to the presence of certain imperfections, constraints and bank-level specificities, a digital euro could possibly alter bank intermediation capacity and such impact could vary across credit institutions. Such impact is found to be potentially larger in stressed times. However, by adequately calibrating CBDC usage limits and remuneration any effects induced by a digital euro on bank intermediation can be managed, even in the event of an economy-wide bank run.

Adalid, R., Assenmacher, K., Álvarez-Blazquez, A., Burlon, L., Dimou, M., López-Quiles, C., Martín, N., Meller, B., Muñoz, M. A., Radulova, P., Rodriguez d’Acri, C., Shakir, T., Silova, G., Soons, O., and A. Ventula, (2022). “Central Bank Digital Currency and Bank Intermediation: Exploring Different Approaches for Assessing the Effects of a Digital Euro on Euro Area Banks,” ECB Occasional Paper Series 293.

Brunnermeier, M. K. and D. Niepelt, (2019). “On the equivalence of private and public money”, Journal of Monetary Economics, 106, pp.27-41.

Burlon, L., Montes-Galdón, C., Muñoz, M. A. and F. Smets, (2022). “The optimal quantity of CBDC in a bank-based economy”, ECB Working Paper Series, forthcoming.

Diamond, D. W., and P. H. Dybvig, (1983). “Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and Liquidity“, Journal of Political Economy, 91(3), 401-419.

European Central Bank (2020), Report on a digital euro, Frankfurt am Main.

Muñoz, M. A. and Soons, O. (2022), “In search of safety: cash, insured deposits, or central bank digital currency?”, ECB Working Paper Series, forthcoming.

Panetta, F. (2021c). “The present and future of money in the digital age”, lecture given at Federcasse, 10 December.

This Policy Note provides a summary of Adalid et al. (2022) and is published simultaneously by Central Banking. It should not be reported as representing the views of the European Central Bank (ECB) or the Eurosystem. Gabriela Silova worked on this paper while employed by the ECB and has in the meantime left the ECB and joined Morgan Stanley. Morgan Stanley disclaimer: “This paper was written in Gabriela Silova’s individual capacity and is not related to her role at Morgan Stanley. The analysis, content and conclusions set forth in this paper are those of the authors alone and not of Morgan Stanley or any of its affiliate companies. The authors alone are responsible for the content.” Carolina López-Quiles worked on this paper while employed by the ECB and has in the meantime left the ECB and joined the IMF. IMF disclaimer: “The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Monetary Fund, its Management, or its Executive Directors.”

To construct the scenarios, we make illustrative assumptions about different use purposes (e.g. retail payments, storage of value) and different demand intensities across sectors and money instruments (e.g. deposits and banknotes). For details, see Adalid et al. (2022). For the “capped” scenario (Take-up C), it is assumed that all residents exhaust a €3,000 limit on their individual holdings whereas non-residents visiting the euro area can hold digital euro exclusively for retail payment purposes. The aggregate figure for this scenario should be understood as an upper bound, as in practice there is a sizeable proportion of euro area citizens that do not hold €3,000 in bank deposits or cash. Adalid et al. (2022) also consider alternative limits (e.g. €5,000 and €10,000).

See, for example, the equivalence result in Brunnermeier and Niepelt (2019).

A bank’s reaction to CBDC demand is simulated using a constrained optimisation model in which a bank is expected to minimise its funding costs, subject to a liquidity constraint, a collateral constraint, a bank specific and system-wide reserve constraints. In the simulation, banks will resort to the cheapest funding option unless they are faced with a constraint. For details, see Adalid et al. (2022).

It is assumed that a bank wants to hold a voluntary buffer above its regulatory requirement (LCR and NSRF) which is at least as high as half of its current liquidity buffer.

A 3-factor Fama-French model is fitted to individual euro area banks’ stock market returns at a daily frequency to identify potentially abnormal returns around events related to the digital euro, or digital currencies more in general. Returns are classified as abnormal to the extent that they deviate from the returns explained by the regularities captured by Fama-French factors. See Adalid et al (2022), and Burlon, Montes-Galdón, Muñoz and Smets (2022) for further details.

See ECB (2020).

Using transaction level data and controlling for potentially confounding factors such as loan demand. See Burlon, Montes-Galdón, Muñoz and Smets (2022) for further details.

See Panetta (2021).

See Adalid, Ramón, et al. “Central bank digital currency and bank intermediation.” ECB Occasional Paper 2022/293 (2022) for further details on the assumptions and specification of the model.

See Muñoz and Soons (2022) for a detailed description of the model and its findings. The set-up is based on the Diamond and Dybvig (1983) framework.