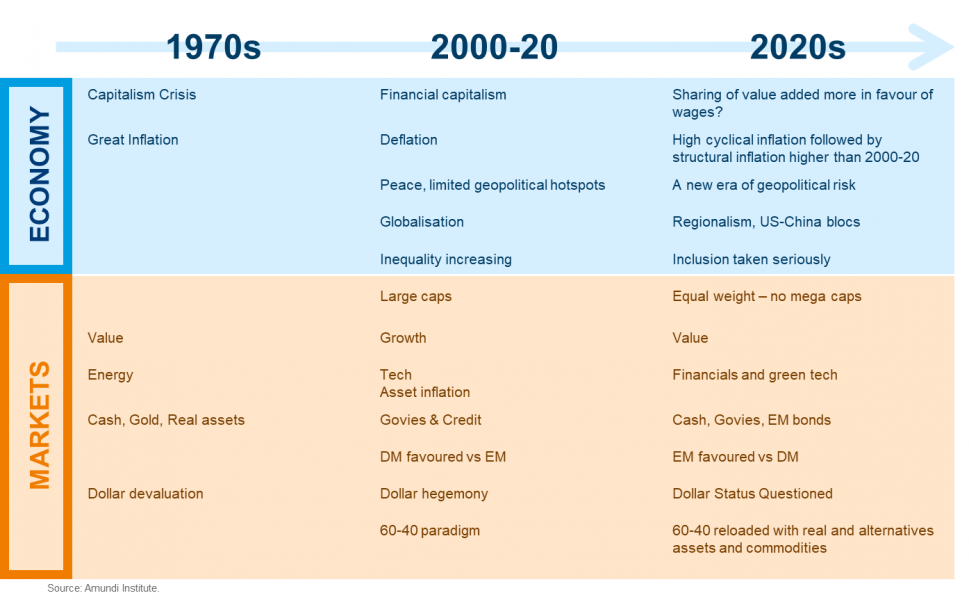

Our view, reinforced by the Covid-19 crisis and the Russia-Ukraine war, that the 2020s bear some similarities with the 1970s has gained traction since 2021, primarily due to high inflation. While the 1970s were followed by structural economic changes that included the triumph of supply-side economics, globalisation and a shift of value-added in favour of capital, there is now a widely shared narrative that incoming transformations will move the opposite way. Despite near-term worries, inflation remains less persistent than during the early 1970s. From a cyclical point of view, it is likely to more easily return to levels closer to targets, especially because monetary policy has been more decisive. Longer term, while arguments in favour of a change in the macroeconomic regime abound, both inflation and growth are likely to be caught in a tug-of-war between opposite forces. There is still uncertainty about the end game, but we expect high volatility in the global cycle, regarding growth and inflation, due to the challenges that lie ahead, such as the energy transition and the road to net zero, and forces in some Developed Economies gaining more strategic independence. The implications for financial markets include changes in correlation dynamics across asset classes (due to expectations of more frequent co-movements of bonds and stocks, lower expected Return on Equity – ROEs), and more regional diversification. Asset class behaviour is likely to be increasingly driven by cyclical swings in growth and inflation dynamics (with a horizon of 1-3 years).

A regime shift vs the past decade, still including some 70s features

Even before the current decade began, and before Covid-19 and the Ukraine war, we believed the 2020s would bear similarities to the 1970s. What happened in recent years has obviously reinforced this conviction. These events began with a sharp surge in inflation, combined with fledgling economic growth (stagflation) starting in 2021. They also extend to some of the certain and presumed causes of this stagflation:

Inflation and monetary policy in the 1970s and their consequences for the real economy

What followed from the early 1970s was a decade of volatile and sometimes very high inflation (with two spikes, in late 1974 and early 1980), which was only tamed by a complete revamp of the monetary policy framework, ultra-high interest rates and a sharp recession (at least in the US). Regarding output, the 1970s also paved the way for a paradigm change for supply-side economics (implemented from the 1980s on, having won the academic debate in the 1970s), deregulation, offshoring, the triumph of so-called “shareholder capitalism”, and several decades of deindustrialisation that deeply disorientated Western lower and middle classes. These changes were accompanied by a shift in the sharing of value-added away from wages and towards capital, both by companies and through housing.

In light of this experience, today’s burning questions are:

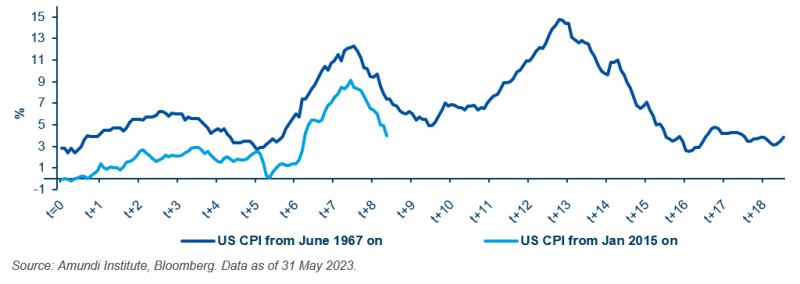

Regarding the short term, there are many differences between today’s inflation and that seen in the 1970s, which lead us to believe price pressures may abate more quickly this time.

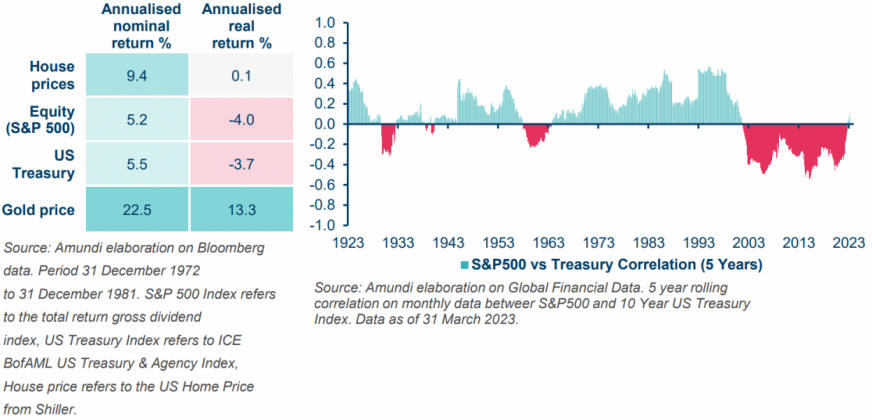

Figure 1: Inflation – 1970s vs early 2020s

Figure 2: Fed’s response to higher inflation

Furthermore, long-term inflation expectations have only slightly moved upwards, signalling that Central Banks’ credibility on inflation is not at risk. Indeed, inflation expectations are a conventional indicator of Central Banks’ reliability, yet are also influenced by the experience of past inflation episodes. In other words, a combination of rational and adaptive expectations. Current economic participants do retain the memory of decades of disinflation. According to basic macroeconomic theory, anchored inflation expectations should help inflation move lower and prevent initial supply shocks from morphing into a prolonged price-wage feedback loop. Little of this existed in the 1970s, as short-term memories were of relatively low inflation and Central Banks had not built specific credibility in this regard (as they tended to pursue and communicate on multiple macroeconomic and financial goals).

Taking these factors into account, a second spike in inflation (similar to that at the end-1970s) is unlikely. At the same time, for Central Banks, bringing inflation back to their targets may not require a deep recession.

Note, though, the caveat here is that the second spike in inflation in the late 1970s was accelerated by a second oil price shock (post-1979 Iranian revolution). Another large geopolitically-driven energy supply shock in the coming quarters or years cannot be ruled out and it is a risk to watch.

Table 1: Differences between the two scenarios

However, even though markets can expect inflation to be less persistent than in the 1970s in terms of magnitude and duration, they must also mind that it could nonetheless trigger more financial, as well as macroeconomic, volatility.

This is largely due to much higher leverage than in the 1970s, be it in public or private (household and corporate) sectors. Firstly, high debt levels mean that governments will be more constrained in how they can respond to economic shocks. Then, debt-related public or private financial accidents cannot be ruled out as a lagged effect of the rise in rates over the past 18 months. Moreover, the valuation of assets has sharply readjusted (in the case of bonds), or may still have to do following the rate hikes (i.e. some illiquid assets). Although the situation appears far less risky than in the pre-Lehman era, we can still see the risk of some shockwaves (through various channels) crossing from asset markets to the general economy. Low market liquidity may amplify them.

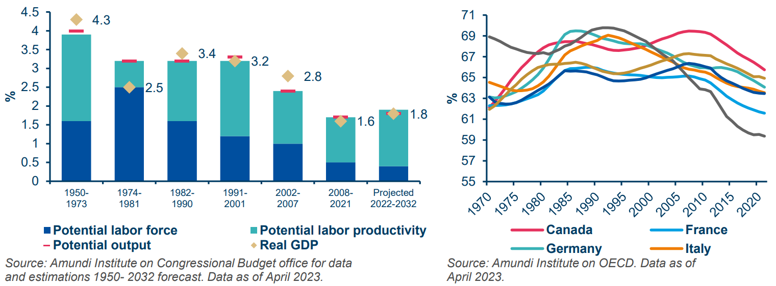

Figure 3: US average real GDP growth and working age population as % of total population, G7 countries

Nonetheless, as of today, the likely features of the new regime are: mildly higher structural inflation (this could mean CBs simply reaching their targets, instead of the frequent 2000-20 undershoots), a slight extension of de-globalisation, growth rates similar to the previous decade, a slightly higher share of the pie directed towards wages at the expense of capital.

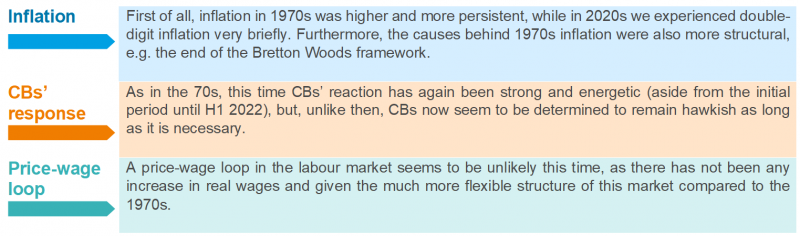

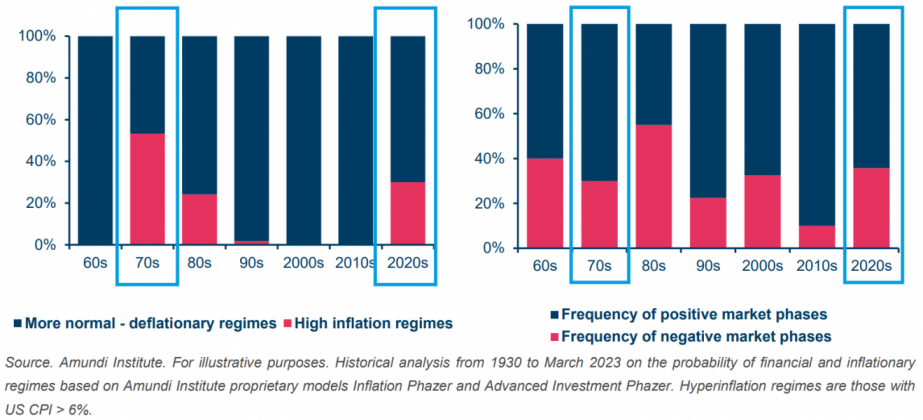

Considering this uncertain environment, financial market adjustments towards a new regime will not be linear. The resurgent inflation episodes of the 1970s and more recently in the early 2020s triggered frequent episodes of negative risk asset performance, as we can see in the chart below.

Therefore, an investment framework able to capture higher volatility in growth and inflation, and an asset allocation able to adapt to different regimes are areas of development needed to assess financial market behaviour.

Figure 4: Frequency of high inflation regimes and Frequency of neg. / pos. regimes for risk assets

Enhanced diversification will be in focus:

A retreat of globalisation or regionalisation, even limited, is likely to lead to less synchronised economic cycles and monetary policies across major economic regions, and thus more value for regional and currency diversification. Moreover, continuing Emerging Markets (EM) growth outperformance, combined with less recycling of EM current surpluses on Developed Markets (DM) (the capital market side of de-globalisation), could lead to EM assets outperforming DM assets.

Due to a possible rebalancing towards wages, margins are likely to represent a smaller share of value added, at least in DM. Therefore, ROEs on DM equities are expected to be lower with an equivalent level of risk. With a longer-term view, and factoring in the consequences of the energy transition (different impacts on growth depending on the countries), real, alternative and EM assets should increasingly be in demand in the search for diversification and higher returns.

Figure 5: Asset class returns in 1972-1981 and Evolution in equity / bond correlation