This article starts from the premise that some European governments may hit their budget constraints during or in the aftermath of the corona crisis. Calls for debt mutualization among European countries are controversial and may not materialize, or not in substantial size. Thus, alternative sources of finance for European firms need to be mobilized.

The European private household sector has large amounts of financial wealth, much of which is parked in deposits and savings accounts remunerated at negative real interest rates. At the same time, due to the economic lockdown, firms which are in normal times perfectly healthy (and should be perfectly viable after the crisis), suddenly face the threat of bankruptcy.

Channeling household savings to firms in the form of equity has so far faced various obstacles. We argue that these obstacles can be overcome by creating a novel institution, the “European Recapitalization and Development Fund” (ECDF), which enjoys savers’ trust given its pan-European nature, the institutions standing behind it (EIB or ESM), professional and transparent governance, and effective portfolio diversification resulting from the large and pan-European nature of its investment activities.

By focusing on equity capital, the ECDF addresses firms’ solvency problems directly.

By being a direct intermediary between savings capital and investment projects/firms, the ECDF avoids the pitfalls of actual or feared transfers between EU states. The funding question would be brought to the level where it ultimately belongs: to savers and firms, instead of being intermediated by political decision making processes and state budgets. Problems of political economy, moral hazard between states, would thus be eliminated.

Problems of capital misallocation, which might come along with state nationalization, would be minimized to the extent that the ECDF, similarly to sovereign wealth funds in oil-producing countries, would ultimately act in the interest of return for its investors.

The Corona pandemic and induced governmental containment measures are currently triggering a massive recession in most European countries. Governments are facing large expenditure needs to cushion the consequences for firms and employees. The resulting rise in public debt ratios has fueled a debate among EU countries on how to help state finances of countries hitting their budget constraints despite ultra-low policy and market rates. First important steps have been taken, e.g. by the creation of the Corona Response Investment Initiative. A further important avenue pursued is the use of ESM funding, as outlined in the Letter of Eurogroup President Mario Centeno to the President of the European Council following the Eurogroup of 24 March 2020. Nonetheless, there is the perception among many policy makers and observers, particularly among representatives from “Southern” European countries,2 that these tools will not be sufficient for state budgets in these countries to cope with the crisis. Various avenues aiming at enlarging “Southern” countries’ fiscal space are currently being debated. The spectrum ranges from combining ESM-conditional financing with Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) financing by the ECB to joint “corona bonds”. For an instructive overview of the breadth of proposals see Bruegel (2020). At least for the time being, positions between “Southern” and “core” EU countries seem hard to square. As a result, the European Council at its meeting of 26 March 2020 could not find agreement on this matter. It mandated the Eurogroup to come up with proposals to support financing EU countries within two weeks.3

A compromise seems difficult. The countries most hit by the crisis feel that they will soon run out of funds to fight the crisis and the costs of rebuilding the economy afterwards. They furthermore argue that also special loans, such as those by the ESM, would just add to their debt burden, and reject economic conditions attached to such loans as interference with national sovereignty. The “Northern” countries by contrast feel that unconditional loans and any sort of large-scale transfers (direct or indirect through joint loans, which might imply transfers in the future) are not justified, given lack of reforms prior to the crisis, ineffectiveness in crisis containment, and the corona-induced huge burden on their own economic system and agents.

How to square this circle? We believe to solve this gridlock, it is useful to widen the perspective. Let’s first ask what is actually the financing problem (Section 2). Then, we will put forward an alternative source of financing, which may take away some of the financing burden from governments and thus help defuse the situation (Section 3). Section 4 concludes.

To widen our options, let’s ask three questions:

There are many areas in the corona crisis, which require large financing volumes. The most important ones are:

Much of the debate so far focuses on debt instruments including loan guarantees, loan deferrals and moratoriums etc. Equity and other forms of state-contingent forms of finance are far less discussed.

Indeed, to the extent that states need financing, they will borrow in the form of debt. However, interest payments and even payment of the principal might be designed in ways to approximate the properties of equity capital, in the sense of making repayment contingent on economic performance. Various forms of GDP linked bonds would be examples of such hybrid forms of “equity-like” forms of sovereign bonds.

Financing needs of the corporate sector will, if stemming from short-term liquidity needs, take the form of short-term debt or guarantees. Longer-term financing needs may take the form of either debt or equity.

In the end, all financing comes from the private sector through private savings or taxation. Also government debt is financed through private bond holders.4

Channeling financing through the state can in extreme crisis situations have important advantages: (i) it can be activated very fast, (ii) big amounts can be mobilized, due to the oiled and long-established practice of sovereign debt issuance, and, (iii) in the case of some countries, it can be comparatively cheap, due to the preferential status of the state and the liquidity of these debt instruments (e.g. US Treasuries) or due a country’s preferential financing terms resulting from safe haven behavior of private savers (who seek protection in “safe” bonds).

But state intermediation of financing the economy can also have a number of downsides, such as various forms of government inefficiencies which may lead to an inefficient allocation of capital. Populist policies, extreme risk aversion in crisis situations, a mentality of “whatever it costs”, ill-targeted policies out of fear to leave groups behind, and even corruption are among the reasons.

If states engage as equity investors (as those calling for nationalisations in fact propose), these inefficiencies may be exacerbated. Experience with the poor performance of state-owned industries and banking systems in Western European and Latin American countries in the 2nd half of the 20th century seem to confirm this notion. It may furthermore be questioned why the state, with taxpayers’ money, should engage in risky activities like an equity or hedge fund. Such risky behavior should ultimately also be reflected in debt financing costs, unless, through financial repression, risk premiums on sovereign bonds are held artificially low, which ultimately in turn puts savers buying sovereign bonds at a disadvantage.

Maybe more importantly, such state-intermediated financing may imply a sizable increase in governments’ balance sheets, and thus gross debt. For countries which already had high debt ratios before the crisis, this may imply that they hit or exceed their borrowing capacity.

In the euro area, such state-intermediated financing then leads to demands that this budget constraint should be alleviated through European-wide state financing tools, such as through the ESM or through Euro bonds alias Corona bonds.

The obvious alternative is to channel also crisis-induced funding directly from private investors to the private sector recipients needing the funding. Before we describe our proposal, two things are worth recalling: first, the corona crisis has reinforced concerns that financing shortages by weakened European firms may make them an easy prey for foreign buyers; but, second, there are ample private savings available in the EU.

The Corona crisis has crashed firm valuations and boosted corporate bond risk premiums. Stock prices in smaller countries/markets (most European countries fall under this category at a global scale) were hurt even more. Obviously, low valued firms represent attractive prey for international takeovers. If firms are even at the brink of insolvency, takeovers could happen virtually at zero cost. Very similar considerations apply to non-listed mid-cap companies, which make up part of the European corporate sector. Lack of access to the stock and corporate bond markets exacerbate their financing shortage.

While virtually all European governments have taken measures to bridge liquidity shortages during the acute phase of the corona crisis and to stretch the need to repay the debt accumulated over several years, this does not solve the problem of the massive loss of equity. In other words, it does not solve firms‘ solvency problems. Even if they do not become insolvent, the crisis-induced erosion of equity ratios (put differently: the increase in leverage) makes them more fragile for the future. Among other things, this also makes them more vulnerable against foreign takeovers.

This has prompted the European Commission to call for a careful screening of inward FDI in strategically important sectors.5 Others are using this concern about the loss of sovereignty to call for nationalizations of large and strategically important firms, with the aim of protecting their viability and to protect them from foreign takeover.

Obviously, global investors are currently evaluating when the best moment to buy equity positions (portfolio or strategic). The stock market rally in the week ending 26 March 2020 already bore witness to this. In the coming months, both during the crisis and in the post-crisis period, substantial additional financing needs to rebuild weakened EU companies will arise.

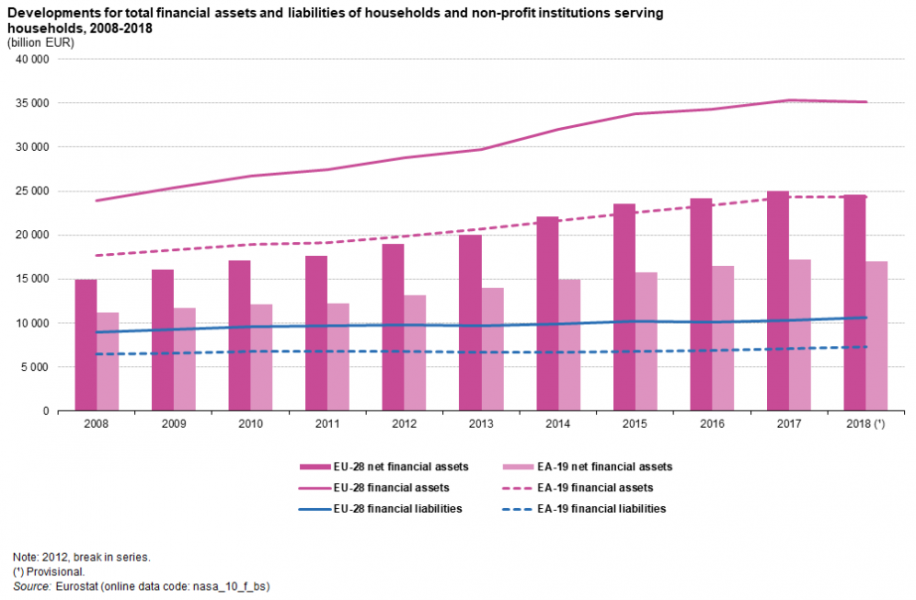

The EU is one of the wealthiest economic regions in the world. Private household financial wealth as at end-2018 amounted to 35 trillion EUR, for the euro area the corresponding figure was around 20 trillion EUR. A substantial part are deposit and savings accounts which have yielded negative real interest for many years. The banks where the savings are deposited face constraints in channeling these savings to companies, given limited risk transformation capacity. This was the case already before the crisis and motivated the initiative to form a European Capital Markets Union, which, however, has so far had limited success.

This European bottleneck in the intermediation of private household savings to the corporate sector, whose business is inherently risky, is being accentuated by the corona crisis and the post-crisis financing needs. Europe needs a quantum leap in post-crisis equity financing.

So if, on the one hand, European firms are undervalued and need equity and, on the other, European savers are suffering from negative real interest rates, why do savers not invest in these firms? What are the current obstacles hampering these two sides from coming together in the common interest? There are likely three reasons. First, behavioural (risk aversion, lack of willingness to invest time, lack of a “stock ownership tradition”), second, lack of knowledge and information (low financial education), and third, lack of trust (distrust in financial industry, GFC experience).

The first two groups of reasons have been the subject of many studies and many initiatives by governments, central banks, financial firms etc. Not much can be expected to be gained on this front in the short run. Thus, it seems most promising to solve the intermediation problem through the creation of a new institution, which aims to mobilize large amounts of equity financing for the European corporate sector quickly. We call this new institution “European Capitalization and Development Fund” (ECDF).

How does the ECDF create trust among investors?

To create trust among investors, the ECDF should be created as a supra-national body. It might be housed and administered by existing EU institutions such as the EIB or the ESM. To benefit from national expertise, it might involve national development banks in the EU member states, who could act as agents at the national level. Actual investment activities might, as usual among central banks and development banks, be mandated to various private sector investment services providers.

To create trust among investors and savers, the ECDF would need to follow transparent and state of the art investment principles, which would include viability evaluations of the firms in which investment is done, requirements on portfolio diversification and avoidance of single large risk positions.

Source of funds: a broad financing base avoiding dominance

Funds could come from institutional investors and retail customers. To alleviate fears of a dominant influence, there could be an upper ceiling on the maximum share which an individual institution or individual can hold in the ECDF.

There could be constraints on non-EU ownership. While not fully in line with the spirit of a pan-European financing vehicle, there might also be upper limits to single European countries’ share in the ECDF (e.g. based on their relative GDP levels), to allay fears of dominance by or a few countries.

To get the ECDF going, an initial capital injection by EU member states, which might or might not reflect a key (e.g. based on GDP) could be foreseen. This injection could in principle also come from only a sub-group of member states.

Forms of finance

Financing by the ECDF should preferably focus on equity, since debt financing is covered by banks and corporate bond markets, as well as by various governmental crisis measures already fully and well underway (such as guarantee schemes, debt service moratoriums etc.).

Both stocks and non-listed equity should be possible. There need to be no limits to the capital share in individual companies held by the ECDF, as long as the size of individual positions is in line with the risk management principles of the ECDF.

There might also be specific specialized branches focusing on large corporations, small-cap financing, or even venture-capital and start-up type financing vehicles.

The ECDF might also finance large-scale European infrastructure projects, which might for instance be initiated in the post-crisis period to stimulate demand and to strengthen the EU’s long-term potential output and growth, such as infrastructure for e-vehicle or H2-vehicle filling stations, smart electric grids, the rapid build-up of 5G, and trans-European networks.

The ECDF’s investment guidelines might reflect sustainable investment principles. This way, Europe’s post-crisis “reconstruction” might be leveraged to facilitate Europe’s transition to a low-carbon, environmentally sustainable economy, which was declared a top priority only a few weeks ahead of the corona outbreak. What before the corona crisis seemed to face unsurmountable financing obstacles, during the post-crisis recovery phase may come to be viewed as a welcome investment opportunity and source of economic stimulus.

This article started from the premise that some European governments may hit their budget constraints during or in the aftermath of the current crisis. Calls for debt mutualization among European countries are controversial and may not materialize, at least not in large volumes. Thus, alternative sources of finance for European firms need to be mobilized.

We argue that the European private household sector has large amounts of financial wealth, most of which is parked in savings accounts remunerated at negative real interest rates. Channeling these savings to firms in the form of equity has so far faced various obstacles. We argue that these obstacles can be overcome by creating a novel institution, the “European Capitalization and Development Fund” (ECDF), which enjoys savers’ trust given its pan-European nature, the institutions standing behind it (EIB or ESM), professional and transparent governance, and the effective portfolio diversification resulting from the large and pan-European nature of its investment activities.

By focusing on equity capital, the proposed ECDF addresses firms’ solvency problems directly.

By being a direct intermediary between savings capital and investment projects/firms, the proposed ECDF would avoid the pitfalls of actual or feared transfers between EU states. The funding question would be brought to the level where it ultimately belongs: to savers and firms, instead of being intermediated by political decision making processes and state budgets. Problems of political economy, moral hazard between states etc. would thus be eliminated.

Problems of capital misallocation, which might come along with state nationalization, would be minimized to the extent that the ECDF, similarly to sovereign wealth funds in oil-producing countries, would ultimately act in the interest of return for its investors.

To be sure, the ECDF would be no panacea and can by no means claim to cover all European post-crisis financing needs. But it may serve as one element in a comprehensive strategy to alleviate demands on public finances during times when they may be close to or at their budget constraint.

The views expressed in this note are the author’s only and do not necessarily reflect official views of the OeNB or the Eurosystem.

See e.g. the letter by 9 EU member states (BE, FR, GR, IE, IT, LUX, PT, SI, ES) to the President of the European Council, dated 25 March 2020, which, among other things demanded: “We need to work on a common debt instrument issued by an EU-Institution to raise funds on the market on the same basis and to the benefits of all MS; … this common debt instrument should have sufficient size and long maturity …to avoid roll-over risks now as in the future.”

See Joint Statement of the Members of the European Council, Brussels, 26 March 2020: “We support the resolute action taken by the European Central Bank to ensure supportive financing conditions in all euro area countries. … We take note of the progress made by the Eurogroup. At this stage, we invite the Eurogroup to present proposals to us within two weeks. These proposals should take into account the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 shock affecting all our countries and our response will be stepped up, as necessary, with further action in an inclusive way, in light of developments, in order to deliver a comprehensive response.”

Even monetary financing by the central bank is paid by private savers through the (future) erosion of the nominal value of savings.

See COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION, Guidance to the Member States concerning foreign direct investment and free movement of capital from third countries, and the protection of Europe’s strategic assets, ahead of the application of Regulation (EU) 2019/452 (FDI Screening Regulation). As EU Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen put it, “If we want Europe to emerge from this crisis as strong as we entered it, then we must take precautionary measures now. As in any crisis, when our industrial and corporate assets can be under stress, we need to protect our security and economic sovereignty.”