Second, temporary increases in thresholds for low-value asset write-offs and depreciation allowances could mitigate the decline of investment, since they effectively reduce the tax liability of firms. The benefit should be felt across all sectors. However, if the contact-intensive sectors have to alter their business structure in order to survive the pandemic and if this requires investment, then this support should be more advantageous to these sectors. For instance, restaurants may adapt their services away from in-person dining and towards takeaway and delivery of food, or redesign the layout of the premises to maintain distance among customers. Such changes necessitate new investment and could be supported by investment incentives through temporary changes in the tax code. They would help maintain sales and profitability.

Third, direct government subsidies such as furlough schemes curb the massive employment loss due to lockdowns. Many countries have helped the hardest-hit sectors retain their workers by providing income support to employees whose working hours have been curtailed or who have been temporarily laid off (OECD 2020a). The scheme enables firms to maintain the contract with them and to preserve workers’ talent and experience. It also deters the decline of production side of the firms, since firms are able to quickly resume operations when the lockdown is eased.

Fourth, many heavily affected businesses have been experiencing a sharp decline in liquidity. To deal with the liquidity shortage, the most common instrument among developed countries has been loan guarantee schemes, where the government guarantees all or part of the bank loans granted to eligible businesses (OECD 2020b). Other measures have included interest-free loans and cash grants. These measures are typically able to target or prioritize those businesses adversely affected by the pandemic, alleviating cash flow difficulties, enabling firms pay suppliers or creditors and, hence, avoid default or bankruptcy.

Finally, subsidies to consumers for consumption of certain goods and services could help the suppliers of such goods and services. This can target the hardest-hit sectors, for example, some governments provided subsidies for eating out or domestic travel.

In general, the delivery speed of stimulus should be a key consideration. For instance, countries may find it timelier to provide loan guarantees, business grants or wage subsidies rather than tax measures. The effect of the latter is only felt at the end of the tax year. In order to achieve prompt delivery, fiscal aid may be provided broadly across all sectors rather than targeting certain sectors, but then this is subject to taxation of regular profit. This would imply that adversely affected firms are able to keep the full amount of support by documenting the hit to their profits, while the firms whose economic circumstances have been affected the least would return some of the support via the tax system (Mankiw 2020; Marron 2020).

There is, however, potentially an unintended side effect of fiscal stimulus. Higher public debt fuelled by the pandemic may harm business and household confidence, creating uncertainty about how public debt would be repaid. To the extent that firms perceive higher public debt to imply higher corporate taxes in the future, this could negatively affect firms’ performance. Note also that wage subsidy programs implemented in some countries may prove to be an innovative yet extremely costly way of sustaining business activities and employment, accelerating government debt. Besides, this support may simply delay the inevitable re-deployment of labor away from unviable firms and may not bring about a particular benefit to the vulnerable firms.

With other stimulus actions such as monetary policy and foreign exchange intervention, unlike fiscal stimulus, the channels of transmission are not as clear. This is partly because it is difficult to target or prioritize specific sectors or firms that have been bruised by the pandemic. Nevertheless, there is some scope for these measures to alleviate the adverse effect of COVID on these sectors.

During the pandemic period, most economies have experienced exchange rate volatility and often intervened in the foreign exchange market. Vulnerable firms engaged in tourism or international trade may disproportionately benefit from such intervention, mitigating a decline of profits and strengthening ability to meet debt obligations.

Expansionary monetary policy may mitigate the effects of COVID-19 on the hardest-hit sectors if firms in these sectors come under pressure from a tightening of credit conditions. For instance, a fall in interest rates may enable vulnerable sectors to ease liquidity concerns and reduce the probability of default.

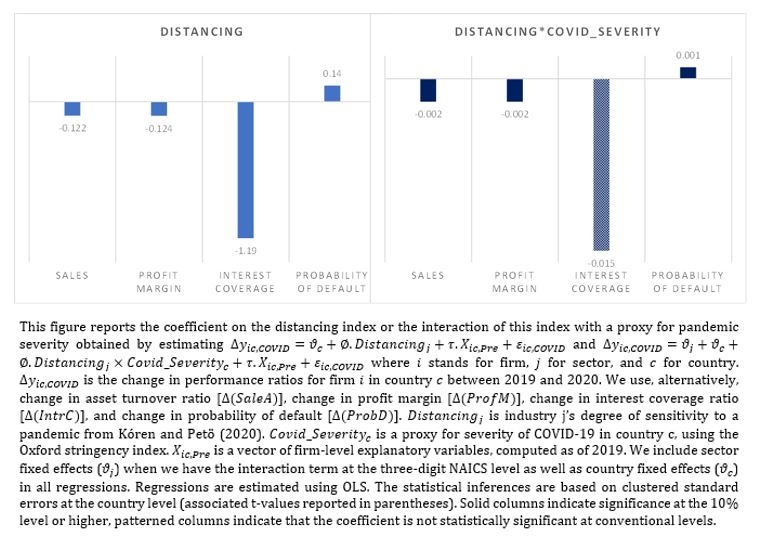

To explore whether policy stimulus packages have given more of a lift to the pandemic-prone sectors, we first confirm that firms in sectors with higher sensitivity to social distancing and lockdown measures performed worse than the others in the same country (Figure 1). This was especially the case when the pandemic hit to their country was more severe (as captured by the stringency of the lockdown measures, which is highly correlated with the reported number of COVID-19 cases and deaths).

Figure 1: Social distancing and firm performance during COVID-19

We then examine whether performance metrics (efficiency, profitability, liquidity, survival) in firms operating in more pandemic-prone sectors have fared better during the first year of the pandemic (2020), if they are located in countries that deployed more comprehensive economic stimulus packages (covering fiscal, monetary and foreign exchange). In other words, if economic policies during the COVID-19 crisis portray an effective action in response to the pandemic, we would expect this to be reflected in relatively better performance by firms that are more pandemic-prone compared to those that are less so. Our main specification, thus, focuses on the cross-sectional differences in firm performance depending on how sensitive to distancing a sector is, controlling for sector and country fixed effects as well as firm observables such as size, age and cash flow.

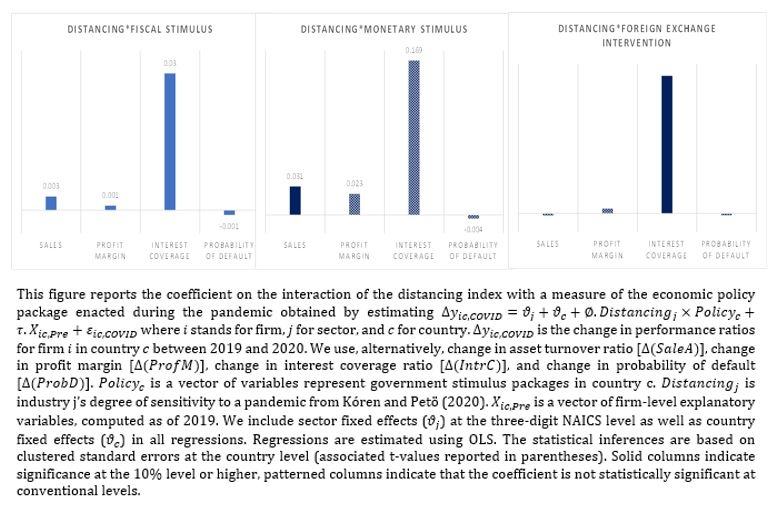

We find a robust positive association of fiscal stimulus with efficiency and profitability (proxied by asset turnover, that is, the change in the sales-to-assets ratio and profit margin, respectively) in pandemic-prone sectors: sales and profitability in firms that are more sensitive to distancing have grown faster when the fiscal stimulus is larger (Figure 2). Furthermore, we observe positive effects of fiscal packages on firm liquidity and survival (as measured by interest coverage ratio and probability of default): interest coverage ratio increased while probability of default decreased disproportionately more in pandemic-prone sectors.

Figure 2: Policy packages, social distancing, and firm performance during COVID-19

Economically, moving from a country at the 10th percentile of the distribution of fiscal stimulus (for example, Sri Lanka) to a country at the 90th percentile (for example, Germany), the change in sales-to-asset ratio of firms in more pandemic-prone sectors is about 2 percent more than their less pandemic-sensitive counterparts from 2019 to 2020. This is consistent with Laeven and Valencia (2013), who report that fiscal policy disproportionately boosted the growth of firms that were more dependent on external financing in the context of the global financial crisis. Aghion et al. (2009) also find that counter-cyclical fiscal policy supported the growth of manufacturing industries across 17 OECD countries over the period 1980–2005.

Additionally, we find that monetary stimulus is marginally associated with an improvement in the sales-to-assets ratio. Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, monetary policy stance in major economies was already accommodative, raising questions about central banks’ ability to confront the next shock (Gagnon and Collins 2019). It appears that further easing has proved to be still effective in improving revenues for firms that were hit hardest by the pandemic. In this respect, the monetary policy transmission mechanism seems to have remained functional during the pandemic, as opposed to the case of the global financial crisis when banks were capital constrained and the lending channel was substantially weakened (Laeven and Valencia 2013).

By contrast, we do not find a robust significant relationship between monetary policy easing and the other firm performance indicators such as liquidity and probability of default. This is in line with the argument that monetary policy may not be particularly well-suited to deal with the implications of COVID-19 because of unsuitability of monetary policy in addressing supply-side shocks and the difficulty to target stimulus to specific sectors that are affected first and foremost by non-pharmaceutical interventions (Chen et al. 2020).

Foreign exchange interventions appear to arrest the decline of interest coverage ratio during the pandemic for the hardest-hit (although this finding is not as robust as those on fiscal and monetary policy measures). One plausible explanation for this finding may be that liquidity in pandemic-prone sectors such as recreation services and tourism is highly responsive to changes in the value of the domestic currency against foreign currencies.

Our findings are robust to a battery of checks, including different strategies to address endogeneity issues and using alternative measures of distancing. We also verify that the results remain broadly the same when we remove certain sectors or industries from the sample. Additional analysis suggests that stimulus packages are generally more effective in larger firms and firms entering the crisis with better liquidity, profitability and capital positions. The latter finding provides some comfort that policy interventions in response to this entirely exogenous shock may not have been distortive.

Our research aims to provide early evidence on the effectiveness of COVID-19 economic policy packages using firm-level data in a large set of countries. Our empirical strategy relies on the varying degree of vulnerability to the pandemic across industries. If policy actions are to be deemed successful, one expectation would be for them to lift pandemic-prone sectors more than others.

There appears to be a robust positive association of fiscal stimulus with growth in the sales-to-assets ratio, profit margin, and interest coverage ratio, and negative association with probability of default in pandemic-prone sectors. Put differently, firms that are more sensitive to distancing have performed better when the fiscal stimulus is larger. There is also some evidence that monetary stimulus has been associated with improved sales and foreign exchange intervention with increased interest coverage ratio for the hardest-hit firms. Overall though, the evidence indicates that fiscal stimulus packages have been more effective than other policies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

An important venue for future research is to expand sample coverage as more data become available and to assess the impact of different policies over longer time horizons. This would shed light on potential side effects and trade-offs that may be associated with widespread economic stimulus.

Aghion, P., D. Hémous, and E. Kharroubi (2014): “Cyclical fiscal policy, credit constraints, and industry growth,” Journal of Monetary Economics 62, 41-58.

Chen, S., D. Igan, N. Pierri, and A.F. Presbitero (2020): “Tracking the Economic Impact of COVID-19 and Mitigation Policies in Europe and the United States,” CEPR Covid Economics 36.

Gagnon, J.E. and C.G. Collins (2019) : « Are Central Banks Out of Ammunition to Fight a Recession? Not Quite,” Peterson Institute for International Economics Policy Brief 19–18.

Igan, D., A. Mirzaei, and T. Moore (2022): “A shot in the arm: stimulus packages and firm performance during COVID-19,” BIS Working Paper No. 1014.

Kóren, M. and R. Petö (2020): “Business disruptions from social distancing,” PLoS ONE 15(9): e0239113.

Laeven, L. and F. Valencia (2013): “The real effects of financial sector interventions during crises,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 45 (1), 147–177.

Makin, A.J. and A. Layton (2021): “The global fiscal response to COVID-19: risks and repercussions,” Economic Analysis and Policy 69, 340-349.

Mankiw, G. (2020): “A Proposal for Social Insurance During the Pandemic,” blog.

Marron, D. (2020): “If We Give Everybody Cash To Boost The Coronavirus Economy, Let’s Tax It,” Tax Policy Center blog.

OECD (2020a): “Supporting people and companies to deal with the COVID-19 virus: Options for an immediate employment and social-policy response,” ELS Policy Brief on the Policy Response to the Covid-19 Crisis.

OECD (2020b): “Tax and fiscal policy in response to the coronavirus crisis: Strengthening confidence and resilience,” ELS Policy Brief on the Policy Response to the Covid-19 Crisis.