This Policy Brief is based on ECB Occasional Paper Series No 334. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Central Bank (ECB).

We examined the net-zero commitments made by Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs). In recent years, large banks have significantly increased their ambition and now disclose more details regarding their net-zero targets. There is also growing convergence, with the vast majority of G-SIBs now being part of net-zero alliances. Despite this progress, some practices should be further improved. The paper gives an overview about disclosure practices with regards to their net-zero commitments. It identifies and discusses a number of observations, such as the significant differences in sectoral targets used despite many banks sharing the same goal, the widespread use of caveats, the missing clarity regarding exposures to carbon-intensive sectors, the lack of clarity of “green financing” goals, and the reliance on carbon offsets by some institutions. The identified issues may impact banks’ reputation and litigation risk and risk management. The paper explains how the introduction of comparable international rules on climate disclosure and the introduction of transition plans, as envisaged and partly already in place in the European Union, could help mitigate these risks.

We examined the net-zero commitments of global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) contained in their publicly available disclosures as of late 2022. 25 of these 30 G-SIBs have made public net-zero commitments. Recently, large banks have significantly increased their stated ambitions and disclosed further details regarding their net-zero targets. There is also growing convergence on the use of net-zero commitments, with, for example, the vast majority of G-SIBs forming part of the Net-Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA). Despite this progress, however, some of the information available in G-SIBs’ disclosures still raise questions at this stage with respect to the consistency with these net-zero commitments. Specific problematic practices include from our supervisory perspective limited information sharing, tentative or merely aspirational language and commitments to unclear goals such as “carbon neutrality”.

While banks widely use the tool of portfolio alignment to illustrate their net-zero convergence, we have observed several areas for improvement relating to the choice of underlying scenarios and pathways and the use of this tool. Banks often select scenarios or pathways that do not reflect their portfolio allocation or geographical exposures. Banks sometimes also use outdated scenarios or benchmarks, or use their own methodologies without providing evidence for their scientific credibility. It is noted, however, that some banks have already announced the use of net-zero scenarios going forward, especially as data gaps are remediated and more granular scenarios become available.

Some gaps also arise with regard to financial institutions’ exposures to certain sectors, as the portfolio coverage of metrics and targets does not systematically allow conclusions to be drawn on the bank’s alignment with the net-zero trajectory. Banks often report their exposure to certain high-emitting sectors but do not cover the rest of their balance sheet, making net-zero assessments difficult. Targets sometimes only cover a narrow selection of sectors or a limited range of activities or subsectors. While many banks have developed and implemented exclusion policies, on closer inspection it is often unclear how such policies contribute to net-zero alignment.

Target-setting could be improved substantially, as the targets are not sufficiently comparable, and the methodological description of the targets is often very vague. We found that while banks have made significant progress in setting and disclosing targets, they have very divergent approaches regarding the selection of base years and interim targets. It is noted that this may currently be due to data gaps and ongoing methodology development. The unclear use of carbon offsets and credits is a further point we noticed, as well as the focus on specific portfolios in the balance sheet and the non-inclusion of facilitated operations in target-setting. It is very complex to assess sustainable finance targets in the absence of a common taxonomy of sustainable activities or a clear and internationally accepted definition of transition finance. In addition, sustainable finance targets rarely cover a significant part of the portfolio to credibly contribute to the bank’s net-zero strategy.

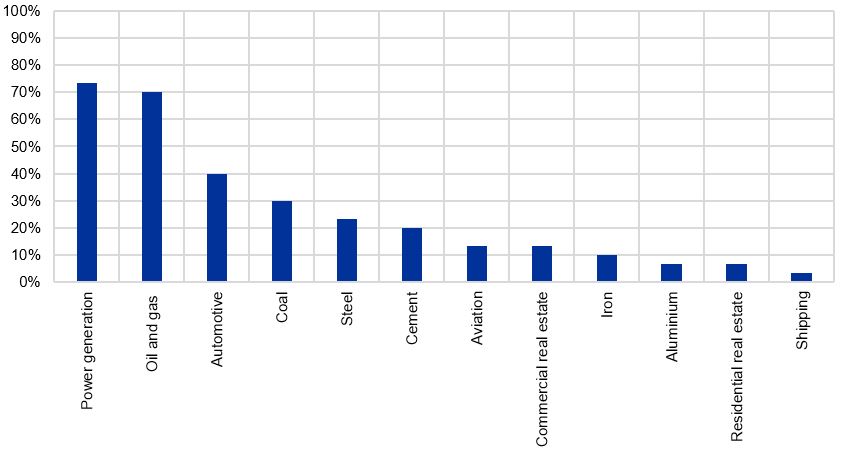

Chart 1: Percentage of G-SIBs with targets per sector

Note: The categories “oil and gas” and “coal” include banks that disclosed targets for energy or fossil fuels.

The highlighted areas for improvement are relevant for supervisors from a prudential perspective. Incomplete or simply poor net-zero commitments could result in litigation and reputation risk in view of recent legal cases, and as such they need to be designed with care and based on facts. Furthermore, these issues can arise from inadequate or malfunctioning internal governance and risk management of net-zero commitments, which, as outlined in the ECB’s guide on climate-related and environmental risks, fall within the mandate of prudential supervisors. As such, we find that it is of a paramount importance to further improve public disclosures.

We conclude by highlighting the need to improve overall comparability and reliability by defining a common minimum framework, further supporting existing market standards. This is already the case in some jurisdictions, such as the European Union, where the disclosure requirements of the Capital Requirements Regulation and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive and the transition plan obligation of the Capital Requirements Directive constitute a common baseline for private initiatives like the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials. These existing frameworks could be further leveraged on. At international level, the combination of interoperable global regulation and privately led initiatives could help establish comparable disclosure requirements, covering both the net-zero transition and associated risks.

On disclosures, the global financial and prudential1 frameworks could be more stringent as regards the choice of metrics and targets and could better reference alignment metrics as well as absolute targets in terms of financed emissions and sustainable finance goals. To this end, they should ensure interoperability with significant privately led initiatives. These targets should cover a material part of the bank’s balance sheet and facilitated operations, while relying on credible, scientifically grounded and regularly updated net-zero scenarios. Banks should disclose how they are actively steering their business and lending portfolios to achieve their net-zero targets.

The integration of a comprehensive transition planning framework into global banks’ risk management processes can help them understand the impact of their strategic actions and risk management tools to achieve net-zero goals, thereby allowing better disclosures. Transition plans ensure that targets and milestones set across different time intervals can be comprehensively embedded in the bank’s day-to-day business monitoring. Banks will also be better equipped to disclose how they live up to their net-zero commitments.

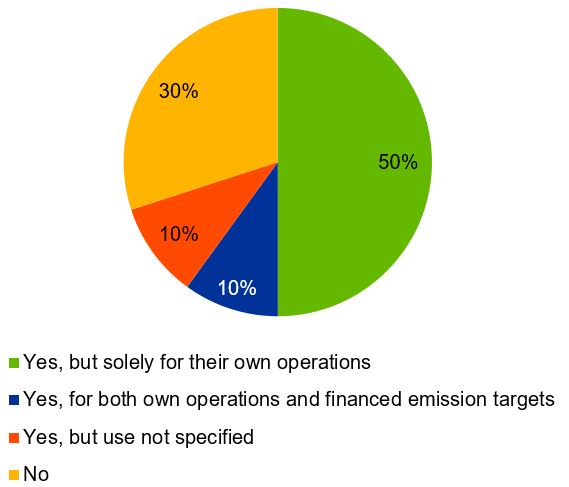

Chart 2: Use of carbon credits/offsets by institutions

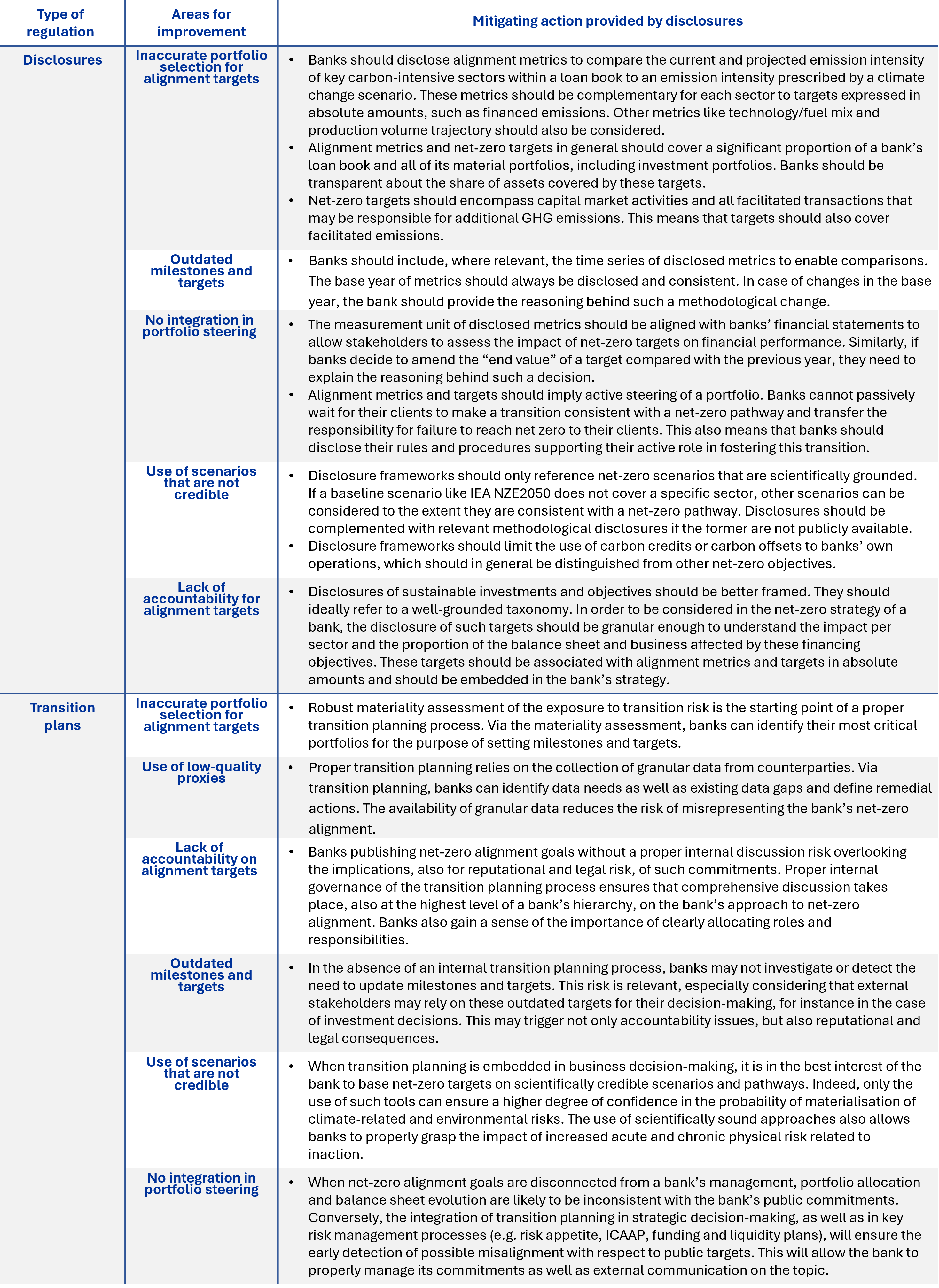

Table 1: Overview of recommendations to address the areas for improvement identified in the paper

Via ISSB standards and the Basel Committee Pillar 3 framework respectively.