This policy brief is based on SSRN paper “The (ir)rationality of firms’ price expectations and the effects on their economic decisions”. The views expressed in this brief are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the positions of Bank of Italy or the Eurosystem.

Abstract

I study how firms form expectations about their own prices and aggregate inflation using data from a rich Italian survey spanning almost twenty years. The empirical analysis reveals systematic deviations from full-information rational expectations (FIRE, hereafter), as firms’ forecasts of their own selling prices are downward biased (i.e. actual price changes tend to be systematically higher than expected ones) and overreact to new information. Similarly, their forecasts of inflation are biased, but they tend to underreact to macroeconomic news. These forecast errors affect firms’ economic decisions, in particular their investment and labour choices, albeit to a limited extent in quantitative terms.

Understanding how firms form expectations about future price developments is crucial for macroeconomic analysis and policymaking (e.g. Coibion, Gorodnichenko and Kumar, 2018). Recent research has highlighted the importance of firms’ expectations for their economic decisions, such as investment and hiring (e.g. Coibion, Gorodnichenko and Ropele, 2020). However, there is limited evidence on how firms form expectations about their own prices, as opposed to aggregate inflation (e.g. Riggi and Tagliabracci, 2022). This policy brief summarises the main empirical findings of a study (Tagliabracci, 2024) that uses data from a unique survey panel of Italian firms to investigate the formation mechanisms of both firm-specific price expectations and aggregate inflation expectations, and to assess the impact of deviations from full-information rational expectations (FIRE) on firms’ economic decisions.

The analysis is based on the Bank of Italy’s Survey on Inflation and Growth Expectations (SIGE), a quarterly survey of Italian firms with at least 50 employees in the manufacturing, services, and construction sectors, whose sample size has increased over time, reaching approximately 1500 businesses in the recent years. The survey collects quantitative information on firms’ past and expected price changes, as well as their expectations about aggregate inflation and their business decisions. The availability of both firm-specific and aggregate price expectations allows for a comparative analysis of their formation mechanisms and tests of rationality by examining the predictability of forecast errors. It also provides an opportunity to examine information rigidities by analysing the relationship between forecast errors and forecast revisions. Finally, the richness of the survey allows us to quantify the impact of forecast errors on firms’ economic decisions through regression analysis that controls for a large number of factors.

Firms’ expectations about their own selling prices deviate from FIRE as forecast errors are predictable due to the presence of a negative bias (i.e. firms systematically underestimate actual price changes) and of a negative correlation between firms’ forecast errors and the corresponding price expectations. Looking at the possible information rigidities (e.g. Coibion and Gorodnichenko, 2015 and Bordalo, Gennaioli, Ma and Shleifer, 2020), firms tend to overreact to news about their own selling prices, suggesting that they may not use their own information optimally. In contrast, firms underreact to macroeconomic news about aggregate inflation, possibly due to inattention to macroeconomic developments.

Firms’ inflation expectations exhibit deviations from the FIRE hypothesis similar to those that characterises firms’ price expectations. Indeed, they also present a downward bias and a negative relationship between forecast errors and the level of expectations. This evidence also holds for the group of firms that receive information about the latest inflation outcome in the survey questionnaire via a randomized control trial (see, for example, Bottone, Tagliabracci and Zevi, 2022). In practice, this suggests that providing information on realised inflation does not mitigate or amplify the existence of this type of inefficiency in their inflation expectations.

Moreover, when it comes to the presence of information rigidities, firms’ inflation expectations are found to underreact to news about aggregate inflation. This is also the case for firms that receive information about the latest inflation data, suggesting that the information rigidities do not depend on the provision of the information about inflation.

Finally, I also test for the existence of the so-called “island channel”, which consists in the use of local information to predict future aggregate developments. This channel turns out not to be quantitatively important, suggesting that firms give very little weight to their specific prices when forming expectations about aggregate inflation.

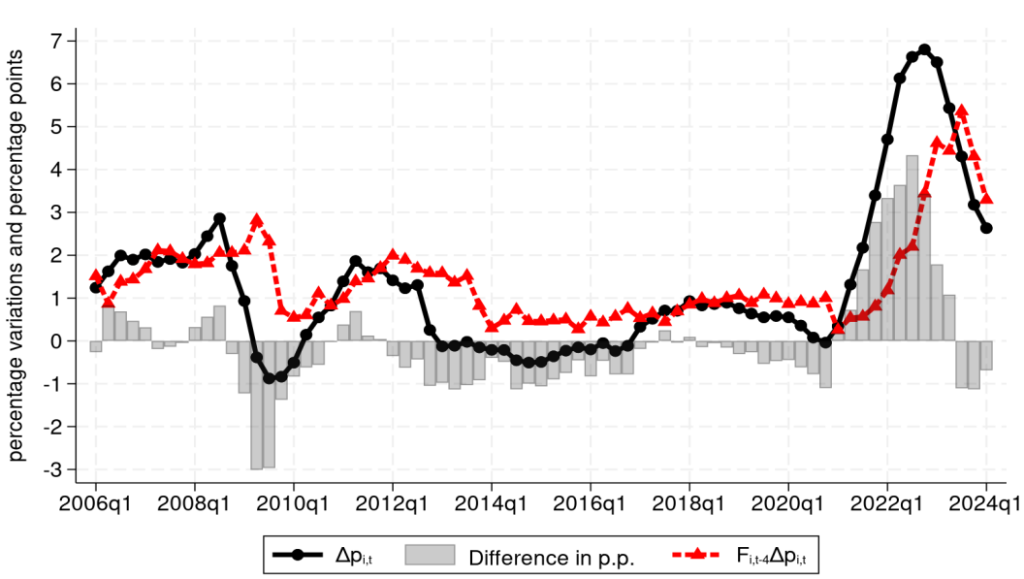

Figure 1. Firms’ expected and actual price changes over time

Note: The black line represents the average price variations of firms’ own prices while the red line corresponds to the expectation of this variation formulated 4 quarters before. The grey bars represent the forecast error in each period.

The richness of the survey allows to study the relationship between managers’ beliefs (and their distortions) and economic decisions by examining how errors in forecasting firm-specific and aggregate variables can affect businesses’ plans and their economic choices (e.g., Ma, Ropele, Sraer and Thesmar, 2020 and Barrero, 2022). While forecast errors on own prices mainly affect labour and investment decisions, they do not have a significant impact on firms’ overall sentiment or perceived conditions about the economy. Errors in forecasting aggregate inflation have a more pervasive effect on firms’ perceptions of economic conditions and may lead to larger effects on decision making. In terms of the sign, firms’ perspective appears to be consistent with a demand-side view of the economy as price changes above expectations are perceived as a positive signal about the state of the economy, leading firms to hire and invest more.

The results highlight the importance of understanding the formation mechanisms underlying firms’ price expectations. The observed deviations from FIRE, such as overreaction to firm-specific news and underreaction to aggregate inflation news, may have implications for the effectiveness of monetary policy and its propagation to the economy, as firms are price and wage setters. Further, exploring how firms weigh the information they gather about aggregate macroeconomic indicators versus the idiosyncratic signals they specifically receive in forming price expectations could provide valuable insights into the heterogeneity of expectations formation and the impact of communication about macroeconomic variables. In addition, assessing the extent to which firms’ expectations influence their pricing strategies and investment decisions would further shed light on the broader economic implications of expectation biases.

Future research should further explore the factors influencing the formation mechanism of firms’ price expectations, particularly in light of the recent rise and subsequent sharp decline in inflation rates observed in many advanced economies. Given that attention to inflation developments is endogenous (see, for example, Weber et al., 2025), understanding how firms learn and adjust their price expectations in different economic environments is crucial for enhancing macroeconomic forecasting and policy-making.

Barrero, J. M. (2022): “The micro and macro of managerial beliefs,” Journal of Financial Economics, 143, 640–667.

Bordalo, P., N. Gennaioli, Y. Ma, and A. Shleifer (2020): “Overreaction in Macroeconomic Expectations,” American Economic Review, 110, 2748–2782.

Bottone, M., A. Tagliabracci and G. Zevi (2022). “Inflation expectations and the ECB’s perceived inflation objective: Novel evidence from firm-level data,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Elsevier, vol. 129(S), pages 15-34.

Coibion, O. and Y. Gorodnichenko (2015): “Information Rigidity and the Expectations Formation Process: A Simple Framework and New Facts,” American Economic Review, 105, 2644–2678.

Coibion, O., Y. Gorodnichenko, and S. Kumar (2018): “How Do Firms Form Their Expectations? New Survey Evidence,” American Economic Review, 108, 2671–2713.

Coibion, O., Y. Gorodnichenko, and T. Ropele (2020): “Inflation Expectations and Firm Decisions: New Causal Evidence,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135, 165–219.

Ma, Y., T. Ropele, D. Sraer, and D. Thesmar (2020): “A Quantitative Analysis of Distortions in Managerial Forecasts,” NBER Working Papers 26830.

Riggi, M. and A. Tagliabracci (2022): “Price rigidities, input costs, and inflation expectations: understanding firms’ pricing decisions from micro data,” Questioni di Economia e Finanza (Occasional Papers) 733, Bank of Italy, Economic Research and International Relations Area.

Tagliabracci, A. (2024): “The (ir)rationality of firms’ price expectations and the effects on their economic decisions”, available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5064016

Weber, M., B. Candia, H. Afrouzi, T. Ropele, R. Lluberas, S. Frache, B. Meyer, S. Kumar, Y. Gorodnichenko, D. Georgarakos, O. Coibion, G. Kenny, and J. Ponce (2025): “Tell Me Something I Don’t Already Know: Learning in Low- and High-Inflation Settings,” Econometrica, 93, 229–264.