The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the ECB or De Nederlandsche Bank.

Over the last two decades, central banks have expanded their monetary policy toolkits, while concurrently credit intermediation via non-bank financial institutions has been on the rise. In this column, we link these two themes and provide empirical evidence on the differential responses of banks and non-banks to different types of monetary policy. We show that standard policy rate changes trigger similar adjustments in the balance sheet size for banks as for investment funds (which is the non-bank sector we focus on in the current study). Non-standard monetary policy triggers stronger adjustments in investment funds than in banks. This highlights that the relative importance of different types of financial intermediaries may also affect the relative effectiveness of different types of monetary policy.

There have been two fundamental shifts in the monetary policy environment of major advanced economies. The first is a significant broadening of the instruments by which central banks have steered their monetary policy stance over the past decade and a half. After previously relying on short-term policy rates as their main lever, the toolkit has become multidimensional. For instance, in many economies central banks now also deploy asset purchases, which differ from policy rates in their transmission to financing conditions and the broader economy.

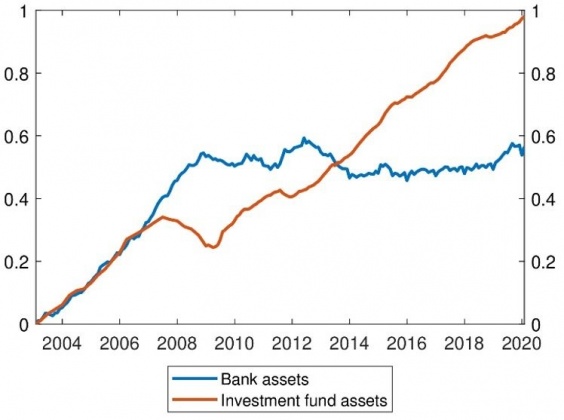

The second fundamental shift consists in the rise of non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs or ‘non-banks’, for short). Whereas banks have traditionally provided the bulk of credit to the real economy, other types of intermediaries, such as investment funds, have acquired an increasingly relevant role in this arena (see Figure 1). As these NBFIs differ from banks in their business models, balance sheet structures, and regulatory constraints, also the latter shift may significantly alter monetary policy transmission.

Figure 1: Balance sheet size of banks and investment funds

Note: Both series normalized to 1 in January 2003 and plotted in log-levels.

In a recent paper, we link these two themes by providing empirical evidence on the differential responses of banks and non-banks to different types of monetary policy (Holm-Hadulla, Mazelis and Rast, 2023). To this end, we set up a standard empirical macro model of the euro area economy and augment it with measures of financial sector balance sheet size. Among non-banks, we focus on investment funds as the type of NBFIs that exhibited the most dynamic growth over recent decades in the euro area (Cappiello et al., 2021). We estimate the model via local projections, using high-frequency information to identify policy shocks, and distinguish between two types of monetary policy: conventional short-term interest rate changes and ‘non-standard’ measures that primarily intervene on longer-term interest rates.

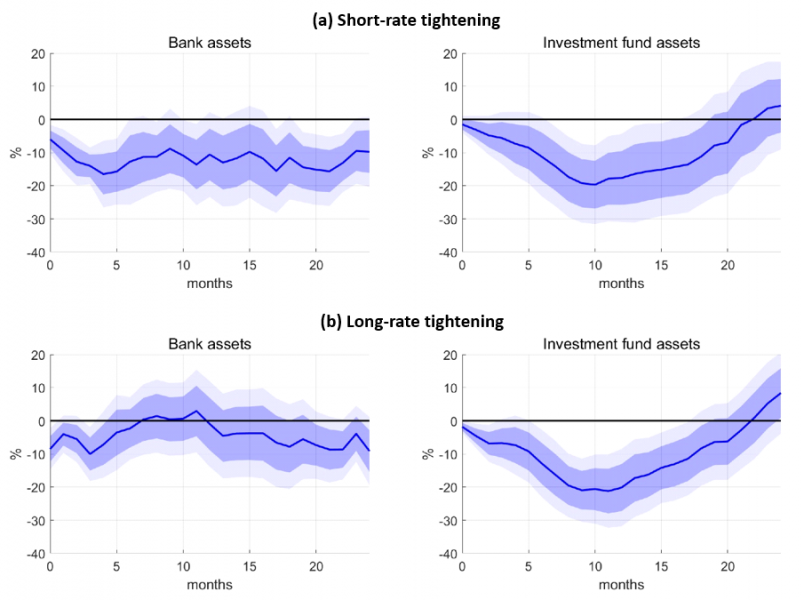

Our results document that banks and investment funds respond differently to monetary policy. After a short-rate tightening shock, bank and investment fund balance sheets both exhibit a significant contraction (Figure 2a). The initial response of banks is slightly stronger and more persistent. But the response of investment funds, while initially more sluggish, then reaches a deeper trough, before returning to baseline towards the end of the IRF horizon. Normalized by its peak impact on the 1-year OIS rate, a 1pp short-rate tightening shock causes a 7.8% maximum contraction in bank assets. The investment fund response reaches a trough of 9.2% below baseline.

After a long-rate tightening, the responses between bank and investment fund balance sheets differ more markedly (Figure 2b). Bank assets initially decline, by a maximum of 4.4%, but the effect quickly fades out. Investment funds instead display a stronger and more persistent response, which is similar to that following a short-rate shock: their balance sheets gradually contract, to a trough of 9.3% after one year, and then revert back to baseline.

Figure 2: Response of bank and investment fund balance sheets

Note: IRFs are normalized to a 1 percentage point monetary policy tightening shock. The dark (light) blue areas correspond to the 68% (90%) confidence interval based on Newey-West standard errors.

These findings suggest that, also amidst the increased role of NBFIs, conventional central bank policy-rate changes remain effective in transmitting to the key sectors that supply credit to the real economy. Moreover, the ongoing shift towards NBFIs may have broadened the transmission of monetary policy, as non-standard measures intervening at longer yield curve segments seem to exert stronger balance sheet adjustments in key constituents of the non-bank sector. As such, the expansion of central bank toolkits and the increasing relevance of NBFI, as the two macro trends motivating our paper, emerge as important complements.

Cappiello, L., F. Holm-Hadulla, A. Maddaloni, S. Mayordomo, R. Unger, L. Arts, N. Meme, I. Asimakopoulos, P. Migiakis, C. Behrens, et al. (2021): “Non-bank financial intermediation in the euro area: implications for monetary policy transmission and key vulnerabilities,” Occasional Paper Series 270, European Central Bank.

Holm-Hadulla, F., F. Mazelis, and S. Rast (2023): “Bank and non-bank balance sheet responses to monetary policy shocks,” Economics Letters, 222.

Ramey, V. (2016): “Chapter 2 – Macroeconomic Shocks and Their Propagation,” Elsevier, vol.2 of Handbook of Macroeconomics, 71-162.