The views here expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Banca d’Italia. This policy brief is based on “Bank lending in an unprecedented monetary tightening cycle: evidence from the euro area”, Occasional Paper (Questioni di economia e finanza) No. 856, Banca d’Italia.

Abstract

Was the weakness of bank lending to euro area non-financial corporations (NFCs) during the ECB’s 2022-23 unprecedented monetary tightening consistent with historical regularities? To answer this question, we use a medium-scale Bayesian Vector Autoregressive model that includes, in addition to macroeconomic variables, credit demand and supply indicators from the euro-area Bank Lending Survey (BLS). The decline in credit growth in 2022-23 is larger than expected on the basis of historical regularities when the VAR is conditioned only on the actual path of interest rates, real GDP and consumer prices. However, when BLS indicators of credit demand and, in particular, credit supply are added to the set of conditioning variables, the gap between the counterfactual and the actual path of lending reduces significantly. This result underscores the increased importance of the bank lending channel in influencing credit dynamics during the 2022-23 monetary policy tightening cycle.

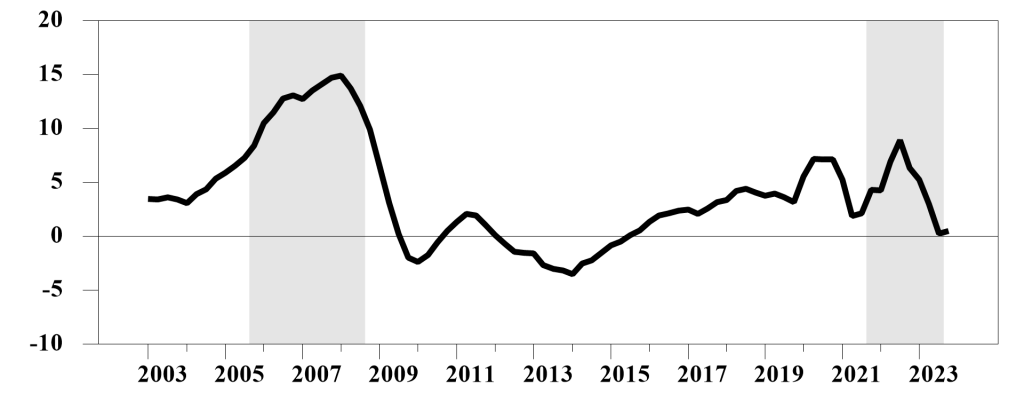

Bank lending to non-financial corporations (NFCs) in the euro area (EA) slowed down markedly during the ECB’s 2022-23 monetary policy tightening cycle. The annual growth rate of loans to NFCs declined from a peak of 8.9 percent in September 2022, reached when firms intensified their recourse to bank lending as a reaction to the adverse energy shock, to 0.5 percent in December 2023 (Figure 1). Since the end of 2023, NFC bank lending in the EA has continued to stagnate. Such a collapse in credit growth is only comparable to that induced by the Global Financial Crisis.

This policy brief uses counterfactual scenarios to show that the decline in the growth rate of loans to NFCs has been steeper than implied by historical regularities, even taking into account the size and the pace of policy rate hikes by the ECB during the 2022-23 monetary tightening cycle.

Figure 1. Annual growth rate of loans to NFCs and monetary tightening cycles

(percentage changes)

Source: ECB.

Notes: The black line plots the y-o-y growth rate of NFCs loans in the EA. The grey shaded areas plot periods of monetary policy tightening, respectively between 2005:Q4 and 2008:Q3 and 2021:Q4 and 2023:Q3

To evaluate whether the recent weakening of NFC loan dynamics aligns with historical patterns, we employ a Bayesian Vector Auto Regression (BVAR) framework, a state-of-the-art methodology also widely used for policy purposes (see for example Lane, 2023; Schnabel, 2023).1

Our BVAR includes macroeconomic, financial, and credit variables. In particular, it incorporates eight endogenous variables: real GDP, HICP (Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices), short and long-term market rates (represented by the € STR and the 10-year IRS, respectively), NFC lending volumes, interest rates on new loans to NFCs, and indicators of credit demand and supply sourced from the euro area BLS. As for credit supply, we include banks’ risk perception, whose sharp increase was a characteristic feature of the last tightening cycle and a key driver of lending rates (Bottero and Conti, 2023). On the demand side, we include firms’ demand for loans to finance fixed investment, which experienced a deep and persistent decline.

We design a series of projection exercises since 2022:Q1 using conditional forecasts. In practice, each exercise consists of three steps. First, we estimate the BVAR coefficients over the sample 2002:Q4-2021:Q4, just prior to the spike in long-term market interest rates driven by the start of the normalisation process of monetary policy and the raising expectations of imminent policy rate hikes.2 Second, we assume that only a subset of the variables included in the BVAR model is known for the full sample until 2023:Q4, while the other variables are only observed until 2021:Q4. Third, we compute conditional forecasts for all unobserved variables over the period 2022:Q1-2023:Q4, based on the estimated coefficients (step 1) and the conditioning set (step 2).

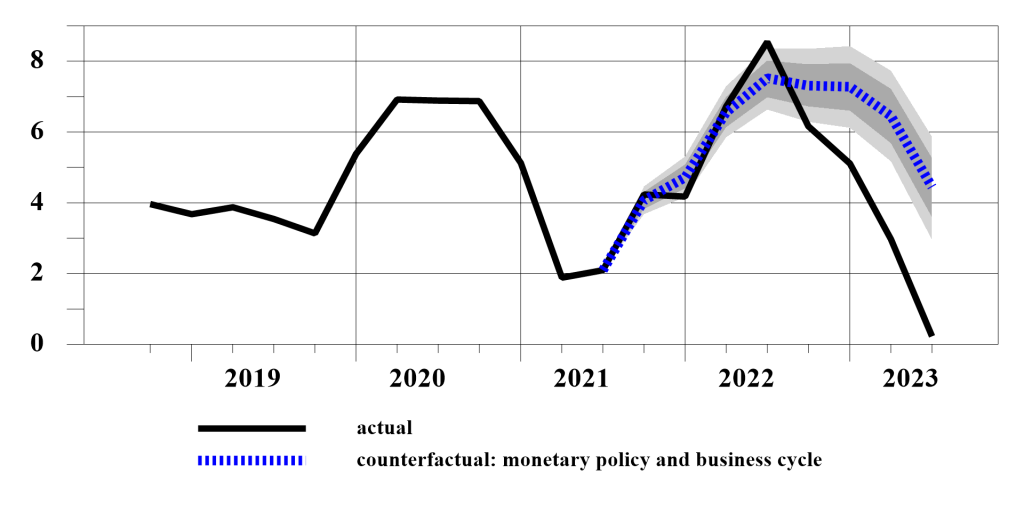

Despite incorporating the actual evolution of interest rates and business cycle variables, the conditional forecasts fail to accurately capture the magnitude and pace of the decline in the annual growth rate of loans to NFCs. In the first exercise, labelled the “baseline” counterfactual, we compute the conditional forecasts including in the conditioning set the observed path of €-STR, 10-year IRS, real GDP and HICP over the period 2022:Q1-2023:Q4 and letting the remaining variables, i.e. lending volumes and rates and BLS credit demand and supply indicators, to evolve endogenously. The counterfactual NFC lending growth tracks the actual dynamics fairly well until the end of 2022:Q2, when firms intensified their recourse to bank lending as a response to the inflation surge triggered by the adverse energy shock (Figure 2). However, the model is unable to replicate the steep decline in loan dynamics which started in the fall of 2022, with a gap between the counterfactual and the actual annual growth rates of about 2.5 percentage points on average until 2023:Q4.

Figure 2. Annual growth rate of loans to NFCs: actual and counterfactual based on monetary policy and business cycle

(percentage changes)

Source: ECB, Eurostat, LSEG and authors’ elaborations.

Notes: the dark (light) grey shaded area is the 68% (90%) credibility interval obtained from the BVAR posterior distribution.

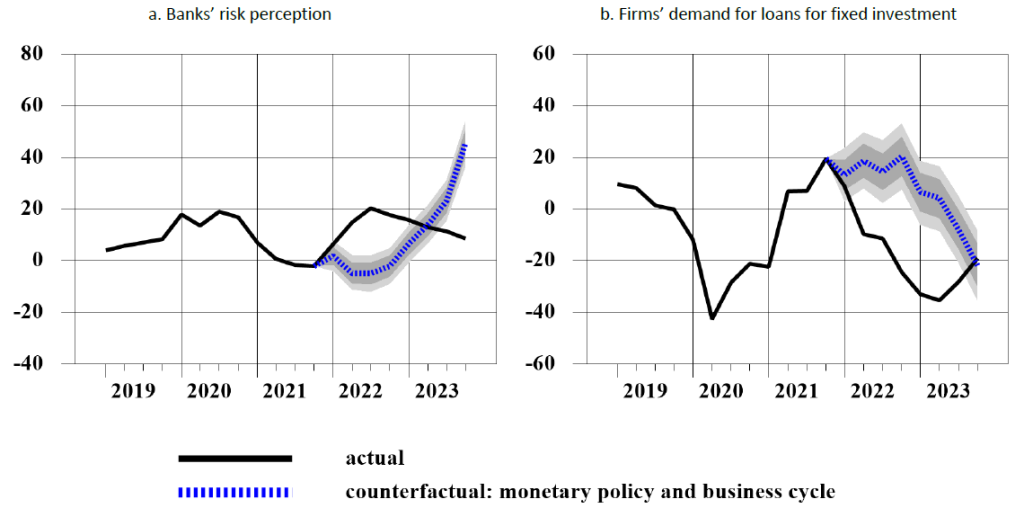

The conditioning set is also inadequate to reproduce banks’ risk perception and firms’ demand for loans for fixed investment. Both the initial rise in risk perception (Figure 3a) and the contraction of firms’ demand for loans to finance fixed investment were faster than implied by historical regularities (Figure 3b), hinting at an amplification of, respectively, the bank lending and interest rate channel.3 The unprecedented scale and speed of the interest rate hikes may explain such an amplification (see also Hernandez de Cos, 2024).

Figure 3. BLS supply and demand indicators: actual and counterfactual based on monetary policy and business cycle

(net percentages)

Source: ECB, Eurostat, LSEG and authors’ elaborations.

Notes: the dark (light) grey shaded area is the 68% (90%) credibility interval obtained from the BVAR posterior distribution.

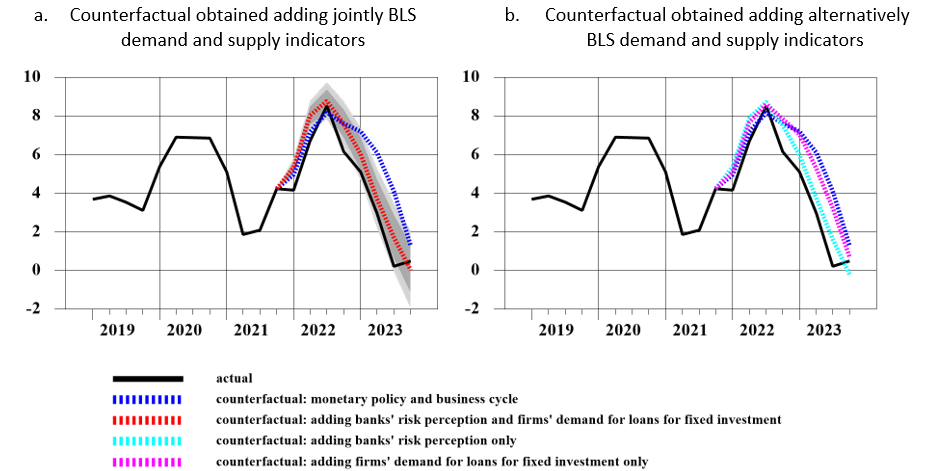

Given the inability of the model to replicate the evolution of the BLS demand and supply indicators, we conduct a second counterfactual scenario, labelled “augmented”, where we expand the previous conditioning set by adding the actual path of banks’ risk perception and firms’ demand for loans to finance fixed investment (observed over the period 2022:Q1-2023:Q4). The counterfactual path of NFC lending growth significantly improves, closely tracking the actual one. This suggests that BLS indicators successfully capture the amplification mechanisms in the bank lending channel and in the interest rate channel during the 2022-23 tightening cycle (Figure 4a).

In a third counterfactual exercise, we add either banks’ risk perception or firms’ loan demand for fixed investment to the “baseline” conditioning set. The results show that banks’ heightened risk perception played a more important role in closing the gap between actual and counterfactual NFC lending growth especially in late 2022, while the contribution from the loan demand factor became increasingly more relevant after 2023:Q3, likely reflecting the usual lags between soft and hard indicators of credit dynamics (Figure 4b).

Figure 4. Annual growth rate of loans to NFCs: actual and counterfactual based on monetary policy, business cycle and BLS demand and supply indicators

(net percentages)

Source: ECB, Eurostat, LSEG and authors’ elaborations.

Notes: the dark (light) grey shaded area is the 68% (90%) credibility interval obtained from the BVAR posterior distribution.

This policy brief provides evidence that during the ECB’s unprecedented monetary policy tightening in 2022-2023 bank lending to NFCs slowed down more than implied by historical regularities. Amplification occurred both via supply (bank lending channel) and demand (interest rate channel).

Our interpretation of the results is the following. While the 2005-08 tightening cycle was mainly driven by a sequence of inflationary demand shocks in a context of robust economic activity and, at least initially, relatively low borrower risk, the 2022-23 tightening was implemented to counter adverse supply shocks which themselves were having severe negative effects on economic growth. The monetary policy tightening amplified the worsening in banks’ risk perception and the reduction of firms’ demand for loans to finance fixed investment that was being driven by the deterioration of the economic outlook caused by the adverse supply shocks.

Given the usual lags with which tighter financing conditions pass-through to the real economy (see, for example, Altavilla et al., 2019), we cannot rule out the possibility that an important part of the effect of the tightening on economic activity and inflation still looms in the pipeline. Moreover, policy rates are expected to remain in restrictive territory even after the ECB starts cutting them (Panetta, 2024) and will continue to affect corporate debt burden and their economic activity. Should this contribute to the persistence of high banks’ risk perception, loans to NFCs could be affected, dampening the expansionary impulse from lower policy rates.

Aastveit, K. A., A. Carriero, T. E. Clark and M. Marcellino (2017). “Have Standard VARS Remained Stable Since the Crisis?”, Journal of Applied Econometrics, vol. 32(5), pp. 931-951.

Altavilla, C., M. Darracq Pariès and G. Nicoletti (2019). “Loan supply, credit markets and the euro area financial crisis”, Journal of Banking and Finance, vol. 109(C).

Auer, S., and A. M. Conti (2024). “Bank lending in an unprecedented monetary tightening cycle: evidence from the euro area”, Banca d’Italia Occasional Paper No. 856.

Bottero, M., and A. M. Conti (2023). “In the thick of it: an interim assessment of monetary policy transmission to credit conditions”, Banca d’Italia Occasional Paper No. 810.

Conti, A. M., A. Nobili and F. M. Signoretti (2023). “Bank capital requirement shocks: A narrative perspective”, European Economic Review, vol. 151.

Hernandez de Cos, P., (2024). “Monetary Policy Transmission and the Banking System”, Speech at the Conference on The ECB and its Watchers, Frankfurt am Main, 20 March.

Huennekes, F., and P. Köhler-Ulbrich (2022). “What information does the euro area bank lending survey provide on future loan developments?”, in ECB Economic Bulletin 8/2022.

Lane, P., (2023). “The banking channel of monetary policy tightening in the euro area”, Speech at the Panel Discussion on Banking Solvency and Monetary Policy, NBER Summer Institute 2023 Macro, Money and Financial Frictions Workshop, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 12 July.

Lane, P., (2024). “The analytics of the monetary policy tightening cycle”, Guest lecture at Stanford Graduate School of Business, Stanford, 2 May.

Panetta, F., (2024). “Monetary policy in a shifting landscape”, Speech at the Inaugural conference of the ChaMP Research Network, Frankfurt am Main, 25 April.

Schnabel, I., (2023). “Disinflation and the Phillips curve”, Speech at the Conference on “Inflation: Drivers and Dynamics 2023”, Frankfurt am Main, 31 August.

This BVAR is a simplified version of the larger model developed by Conti et al. (2023) for the Italian economy, but augmented by the two “soft” BLS indicators. For more details on the specification see Auer and Conti (2024).

In December 2021, the ECB announced its decision to discontinue the net asset purchases under the Pandemic Emergency Purchases Programme (PEPP) at the end of March 2022. The PEPP was very effective in stabilizing financial markets and lowering sovereign bond yields (see, among others, Bernardini and Conti, 2023).

Since 2023:Q2, the realized actual evolution of banks’ risk perception has been somewhat lower than the counterfactual one, likely reflecting the delayed adjustment of the model. Nevertheless, since it is well known that BLS supply indicator lead loan growth by about 4 quarters (Huennekes and Köhler-Ulbrich, 2022), banks’ risk perception likely weakened loan dynamics in 2024.