The opinions expressed in this column are our own and not necessarily those of Banca d’Italia or the Eurosystem.

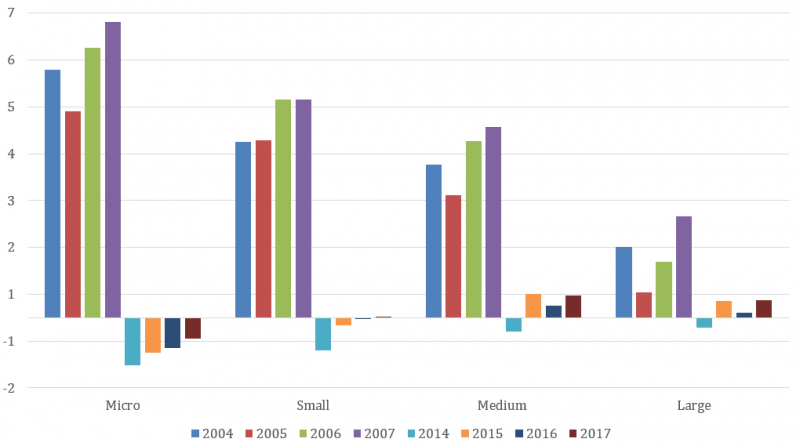

(as a percentage of firms’ total assets)

In accordance with Commission Recommendation 2003/361/EC, SMEs employ fewer than 250 persons and have either an annual turnover or annual balance sheet total not exceeding EUR 50 million and EUR 43 million respectively. In particular, micro-firms and small businesses employ, respectively, fewer than 10 and 50 persons and have either an annual turnover or annual balance sheet total not exceeding EUR 2 and EUR 10 million. In our sample, their weight in terms of granted loans during the period 2014-2017 was 21 per cent for micro-firms, 20 for small ones, 22 for medium-sized ones and 37 for large companies.

The analysis is based on around 730,000 matched bank-firm data per year referred to 255,000 non-financial Italian limited companies and over 800 financial intermediaries (of which near 500 banks accounting for nearly 90 per cent of total credit). For the sake of simplicity in the following we use the term ‘bank’ to indicate a financial intermediary, either bank or other financial companies. Outstanding loan amounts are drawn from the Italian Central Credit Register, which is managed by the Bank of Italy; annual non-financial firms’ balance sheet and income statement data are taken from the Cerved database; Bank of Italy‘s supervisory reports are also used to include information on banks’ annual balance sheets and income statements at the individual level.