Over the last two decades, bank stress tests have progressively become a key tool at the disposal of banking supervisors. Not only policy makers but also the financial industry and academics have increasingly relied upon them. In particular, stress tests gained a lot of attention after the Global Financial Crisis as it became clear that a sound financial system was a necessary condition for a healthy worldwide recovery. Very often criticized, very little is known however about their whole philosophy, their methodology and how insightful they can be in shedding light on the main mechanisms at risk within a banking sector in case of a crisis. This note tries to provide the reader with a better understanding of this prudential tool. Moreover, at a time when fiction seems to meet reality, the recent Covid-19 crisis has not only revealed the importance of these exercises for policy-making and communication, it can also represent a great opportunity to reflect on ways to improve them.

In order to ensure banks’ resilience from macroeconomic and financial shocks, prudential authorities across the globe have been using a range of risk analysis tools, among them the now well-known and highly mediatized bank stress tests. As prudential authorities realized that sufficiently well-capitalized banks were key to ensure that an initial adverse shock hitting the economy or a financial system would not be amplified, stress tests became part of the regulatory framework in 2004 under the Basel II accords. These accords authorised banks to develop their own in-house risk models in order for them to compute their capital requirements. At the same time, however, it also became clear that supervisors needed stress-test tools to check the soundness and the relevance of the different models considered by banks and run their own analysis on the banking sector as a whole. With the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, these exercises became even more useful, notably for evaluating and communicating on banks’ ability to withstand a shock of that scale. As a result, the Basel Committee introduced its Principles for sound stress testing practices and supervision in 2009. At the European level, stress tests have since become a recurrent exercise and are carried out every two years by the European Banking Authority (EBA). However, what are they? What purpose do they serve?

This policy note, which echoes two recent Banque de France’s blog posts on bank stress tests (see blog 1 and blog 2), first explains the underlying philosophy behind these prudential tools and their general methodology (section 1). Moreover, unlike the fictitious scenarios used in standard prudential stress test exercises, the Covid-19 crisis represents an unprecedented adverse scenario. Section 2 draws some first conclusions on the resilience of the banking system, as observed for the time being and discusses the essential role of communication around these stress tests. In the light of this experience, this note concludes on the main lessons that can be drawn and reflects, in particular, on different ways bank stress tests could be improved.

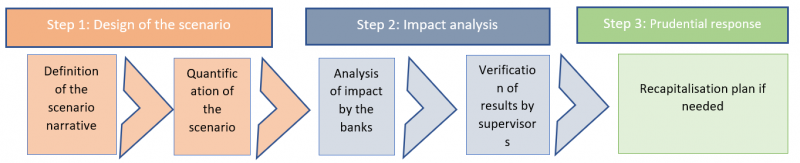

Chart 1: Steps in a bottom-up bank stress-test exercise

1.1. Anticipating adversity and ensuring the sound financing of the real economy by banks

What is the entire process behind each stress test exercise? A stress test consists in simulating the impact of an economic and financial crisis on each of the tested banks and, by extension, on the solidity of the banking system. Since 2009, 6 European stress tests have been carried out, each involving three steps (see Chart 1):

1.2. The capital ratio: the stress-test thermometer

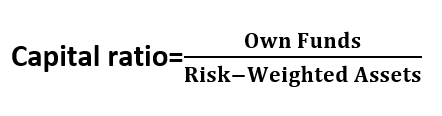

The loss of capital revealed in a stress test is expressed in terms of the decline in the “capital ratio”. A bank’s capital (or solvency) ratio corresponds to the amount of bank’s own funds expressed as a percentage of its risk-weighted assets (RWA), i.e.:

Risk-weighted assets are defined as the sum of each line of a bank’s balance-sheet exposure multiplied by a weight that reflects that exposure’s level of risk. Different exposures are treated differently.5

The capital ratio is thus a useful thermometer to measure bank’s financial soundness. Any deterioration can be the result of (i) a decline in bank’s capital generated by losses and often referred as a numerator effect and/or (ii) a rise in its risk-weighted assets (denominator effect). A bank is deemed fragile if, under the stress test scenario considered, its capital ratio is found to fall below the minimum requirement imposed by the regulation and which is specific to each institution depending on the risks it is exposed to. Chart 2 shows the capital ratios in December 2019 of the 22 largest banking groups in the European Union.

Chart 2: Solvency ratios (%) of the 22 largest banking groups in the EU at end-2019. Available data at end-2019.

Source: SNL.

1.3. Risk analysis conducted by the supervisors

Because of its role in financing the real economy, a bank is exposed to a number of risks for which it needs adequate capital coverage. An adverse scenario can have an impact on various classes of risk. In particular, credit risk corresponds to the actual or potential losses that a bank could incur through its lending activities and that could result from its borrowers’ inability to honour their commitments. Market risk is directly linked to fluctuations in asset prices (government and corporate bonds, equities, derivatives, etc.) while operational risk results, for example, from frauds, natural disasters or cyber-attacks.

The channels whereby these risks are transmitted are complex and differ according to each bank’s business model. Here is a non-exhaustive list of channels typically scrutinized by regulators:

An economic downturn reduces banks’ income by slowing demand for new loans (due to a fall in investment and consumption, for example). It also affects borrowers’ (businesses and households) income levels, which may undermine their ability to reimburse their loans. Default losses on secured loans also tend to increase as prices of the assets pledged as collateral fall sharply (e.g. residential real estate in the United States during the 2008 Great Financial Crisis). These amplified risks of potential non-repayment or of a loss in collateral value translate into a rise in banks’ capital requirements, while the losses incurred reduce their income.

The overall increase in investors’ risk aversion raises banks’ funding costs (cost of debt or capital on the liabilities side). Banks may in turn decide to pass these higher costs on to the interest rates charged to borrowers. This may be the source of extra financial difficulties for businesses, households that need to renew their loans, or that borrow at floating rates, slowing the economic recovery and even amplifying any initial credit risk shock. Conversely, if banks decide not to pass on the rise in their funding costs to their lending rates, their interest margins shrink and so does their income.

Under the coordinated stress-test exercises, prudential authorities determine the way banks consider these transmission channels, to ensure consistent treatment and comparability of results. In practice, banks are notably required to use a static balance sheet approach: in other words, they must assume throughout the entire stress test that they do not optimise their balance sheet in response to the shocks but instead undergo them “passively”.

As the health crisis started to unfold, prudential authorities quickly resorted to stress tests for them to assess to what extent the banks under their supervision would be able to absorb the shocks and ultimately not jeopardize the financing of the real economy.

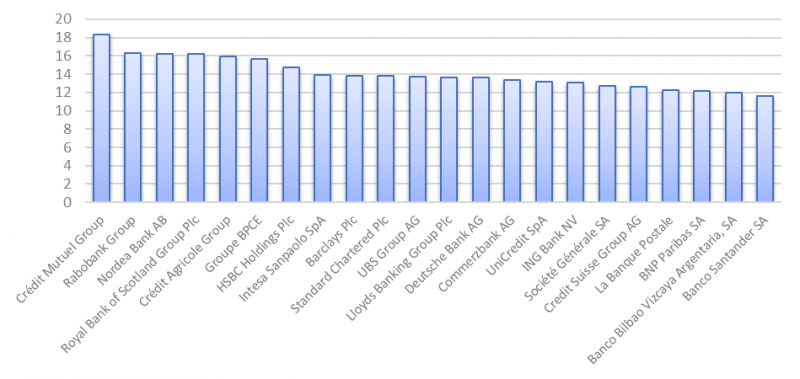

2.1. The impact of the Covid-19 crisis: a more severe forecast than the scenarios tested since 2010

Even if there remains considerable uncertainty surrounding the potential impact of the Covid-19 crisis on banks, the lessons learnt from the stress test exercises can be particularly useful in this context. In practice, since the stress tests started being implemented in 2009, the severity in terms of GDP shock of the scenarios used (measured with respect to the deviation from the forecasts’ central scenario) by the EBA has increased. Nevertheless, the severity of the scenarios used up until the 2018 exercise appears to be weaker than that of the current shock as estimated for France in the Banque de France forecasts dated June 2020 (in terms of deviation from the December 2019 forecasts – Chart 3). The ECB used this shock in terms of deviation from the forecasts (December 2019 vs. June 2020) to conduct a stress test known as “Vulnerability Analysis” in June 2020.

Chart 3: GDP losses considered for all the EBA and the Covid-19 stress-test scenarios and the ones observed during recent crises, (in %)

Note: The figures correspond to the 2-year cumulative difference between the adverse scenario and the baseline scenario. For the Covid-19 crisis, the figures are the differences between the December 2019 and June 2020 Banque de France forecasts. For the Global Financial Crisis, the graph shows the difference for France between the ex-post observed GDP and the European Commission’s spring 2008 GDP forecasts.

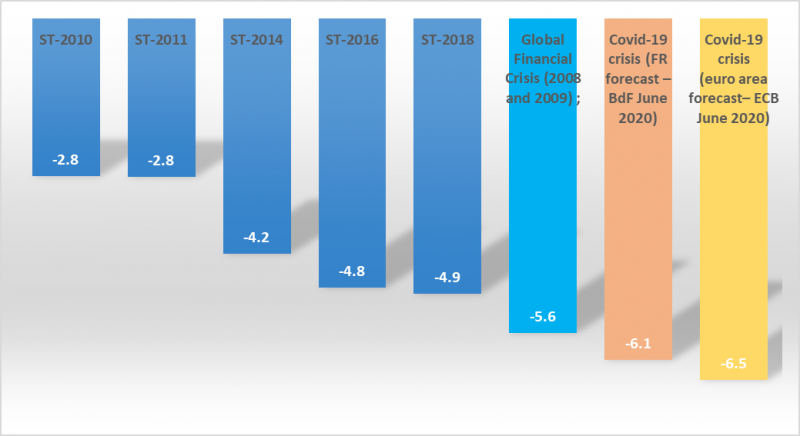

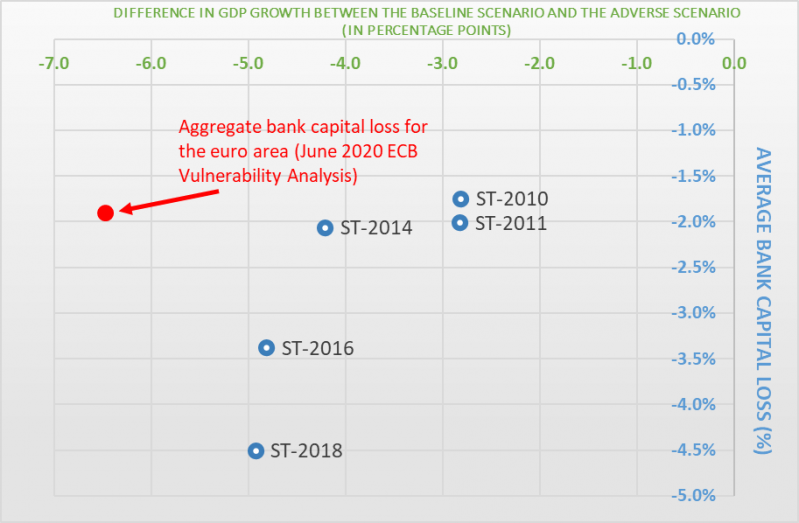

Chart 4 shows a close relationship between, on the one hand, the annual GDP shocks considered in the scenarios of the previous EBA stress tests and, on the other, the estimated capital ratio losses for the French banking system. It should be noted that other assumptions, such as, for example, those concerning the evolution of the interest rates and asset prices (equity shares and real estate), are also key in standard stress test exercises.

Chart 4: GDP losses and bank capital losses for the different stress tests

(France – blue; euro area – red).

Note: the average bank capital loss of French banks and the average GDP (in blue: France, in red – EA) are assessed over a 2-year horizon.

Since 2010, the EBA has always considered worse and worse GDP shocks for their adverse scenarios. Without any surprise, the capital losses estimated for the French banking sector have also been increasing with the different vintages. However, it is important to analyze these projected capital shortfalls with respect to the initial situation of credit institutions’ prudential ratios at the time of each exercise: banks are comparatively much better capitalized at the end of 2019 than in 2010. On average, their capital ratio is around 5% higher in France. In other words, everything else being equal, banks are better able to absorb macroeconomic shocks without jeopardizing their ability to finance the real economy nowadays than 10 years ago.

In June 2020, the ECB/SSM (European Central Bank/ Single Supervisory Mechanism) conducted a stress test exercise, known as the “Vulnerability Analysis” and amply justified by the Covid-19 crisis, for all the EU banks considered as systemically important. This stress test which was not anticipated 6 months before did not disclose results by country. A specificity of this exercise is worth mentioning: it partly takes into account the measures adopted by the different governmental, supervisory authorities and central banks. While standard stress test exercises do not typically model the endogenous policy makers’ reactions, these measures act as shock absorbers in the “Vulnerability Analysis” simulation. Consequently, comparing the results for the Covid-19 crisis with the ones obtained for previous stress-tests, despite the different methodologies, assumptions, samples and initial balance sheets considered, allows us to give an approximate, even though far from perfect, assessment of the expected effects of these support measures. Indeed, Chart 4 suggests that the various support policies should absorb a large fraction of the impact on the European banking system. The depletion in CET1 projected for the “Vulnerability Analysis” is relatively close to the one that had been estimated for the 2010, 2011 and 2014 EBA exercises while the GDP shock considered is twice as large.

Moreover, as in standard EBA stress test exercises and their “static balance sheet” approach, they do not take into account banks’ managerial responses to the crisis.

2.2. A key communication tool, especially in the context of the Covid-19 crisis

Communication around these exercises is essential. It provides investors, but also bank clients, with information on banks’ ability to withstand a major crisis. However, this communication is tricky:

In all cases, communication must be sufficiently transparent to enable everyone to assess the resilience of the banking system while limiting the risk of self-fulfilling prophecies.

In the context of the Covid-19 crisis, the ECB/SSM, the Bank of England, the Bank of Canada and the US Federal Reserve have each communicated on their stress test exercises. The results should be interpreted in the light of the perception of the Covid-19 crisis and the still highly uncertain environment at the time of their publication. In particular, they were conducted before the second wave of lockdowns carried out in many countries in autumn 2020. Unlike the standard exercises involving banks (the so-called “bottom-up” approach), these were entirely conducted by supervisors (a “top-down” exercise). Moreover, they do not simulate a fictitious scenario but rather aim at predicting the impact of the Covid-19 crisis on banks’ health. They are thus more akin to forecasting exercises (i) with a highly uncertain economic recovery scenario and (ii) a methodology that is entirely based on the supervisory authorities’ models and therefore does not involve banks. In these “top-down” exercises, banks’ individual characteristics are less well integrated and further work is needed to possibly calibrate individual requirements in terms of capital strengthening. Only the aggregated results have therefore been published.

At the end of July, the ECB/SSM published the aggregated results for the 86 banks that it supervises and which are based on the analysis of three scenarios: (i) the pre-Covid-19 macroeconomic forecasts made at end-2019, (ii) the central forecasts published by the ECB in June 2020 (which corresponds to the Vulnerability Analysis point in Chart 4) and, finally, (iii) a more adverse scenario involving a deep and lasting recession. Thus, according to the SSM, the EU banking system is expected to experience an aggregate capital ratio loss of 1.9 percentage points in the central scenario (as forecasted) and a more significant impact (of around 5.7 percentage points) in the case of a more severe scenario than the forecasts for 2020.

While stress tests have become a vital risk management tool for prudential policymaking over the last few years, both in the United States and in Europe, the doctrine, the models used and even the lessons to be drawn have not yet been harmonised across jurisdictions and are de facto still the topic of intense debates. They nonetheless remain an extremely useful exercise that provides visibility over the banking system’s ability to withstand adverse shocks and support the economic recovery in less favourable times. It should also be remembered that, at the European level, they are used as benchmark for the calibration of certain bank capital requirements, especially those known as Pillar 2.

More specifically, the 10-year experience of conducting bank stress tests and the recent episode of Covid-19 provides us with several lessons for the future of stress-test exercises.

To sum up, while the importance of bank stress tests has once again been highlighted by the Covid-19 crisis, these exercises are not uncritical and many avenues for improvement could be explored. They nevertheless prove to be useful and complementary tools for individual bank supervision. It also seems necessary to examine these questions at the international level.

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Banque de France nor the Eurosystem.

Typically, the main simulated variables are the growth rate of the gross domestic product (GDP), the unemployment rate, short and long-term interest rates, equity prices and real estate prices.

Under the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), this response is the responsibility of the ECB, working in close collaboration with the national supervisors.