This policy brief is based on ECB Working Paper Series, No 3031. This policy brief represents the authors own views and does not necessarily represent the views of either the ECB or the Eurosystem.

Abstract

How does bank transparency influence market efficiency? This paper examines the impact by comparing banks that disclose their supervisory capital requirements with those that remain opaque. Given that these requirements provide critical information to the market, opacity could hinder market efficiency. The findings suggest a transparency premium—banks that disclose their supervisory capital requirements benefit from 11.5% lower funding costs compared to opaque banks. Transparency allows markets to distinguish between safer and riskier banks more effectively. Among transparent banks, the safest experience the most significant benefit, enjoying 31.1% lower funding costs on average. Transparency enhances market discipline by enabling investors and stakeholders to better assess and price risk. This supports the case for greater disclosure in banking regulation, reinforcing market efficiency.

In recent years, there has been a general trend toward increased transparency of banking supervisors. In the European Union for instance, according to the European Capital Requirements Regulation 2 (CRR2), since June 2021, all banks are mandated to disclose their Pillar 2 Requirements (hereafter, P2R). The P2R establishes the minimum capital threshold that Euro- pean banks must maintain to be assessed as solvent by supervisory and regulatory authorities in the European Union. Non-compliance with this requirement may result in supervisory actions, including sanctions and assessments of failure.1 In anticipation of this regulatory change, in January 2020 the euro area Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM henceforth) published, for the first time, bank-specific data on P2Rs following a supervisory transparency initiative and its annual assessments within the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP).

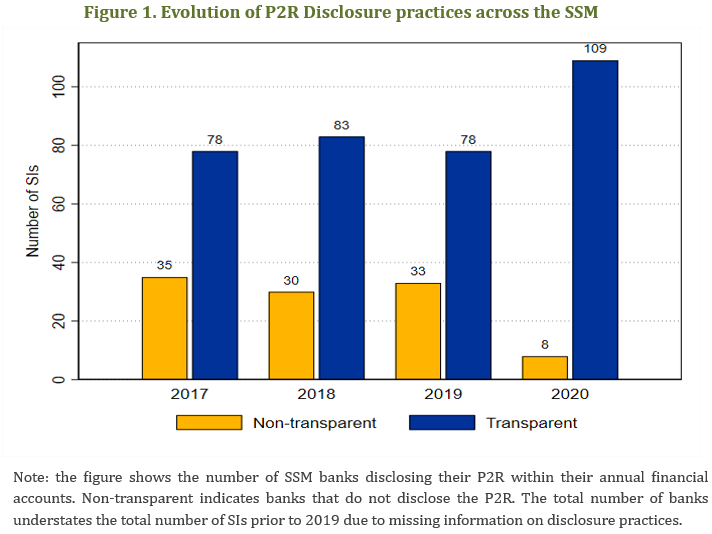

Figure 1 shows the evolution of P2R banks’ disclosure practices from 2017. Until January 2020, only 69% of the 120 Significant Institutions (SIs) supervised by the SSM published their P2R, either due to obligation under the provisions of the EU Market Abuse Regulation (MAR) or on a voluntary basis. Due to the SSM transparency initiative, in 2020 the number of publicly available P2Rs has increased significantly and, at that time, only a small number of banks has not yet disclosed the P2R but for operational reasons. As of January 2024, all banks supervised centrally by the SSM disclose their P2R.2

In a new paper Beyer and Dautović (2025), we inform on whether the SSM transparency initiative is improving market efficiency by steering markets to grant better funding terms to safer and sounder banks.

In theory, disclosure of supervisory requirements can improve market efficiency by reducing asymmetric information and promoting the allocation of resources to the most productive uses, Hirshleifer (1971), Allen and Gale (2000) Leuz and Verrecchia (2000). This is because disclosing information about supervisors’ assessment allows market participants to distinguish banks “in good shape” from banks ‘in bad shape’, and to reward the former according to their performance and risks, exercising ultimately discipline on banks and cushioning their risk-taking incentives, Bischof and Daske (2013), Bischof et al. (2021, 2023), Acharya and Ryan (2016).

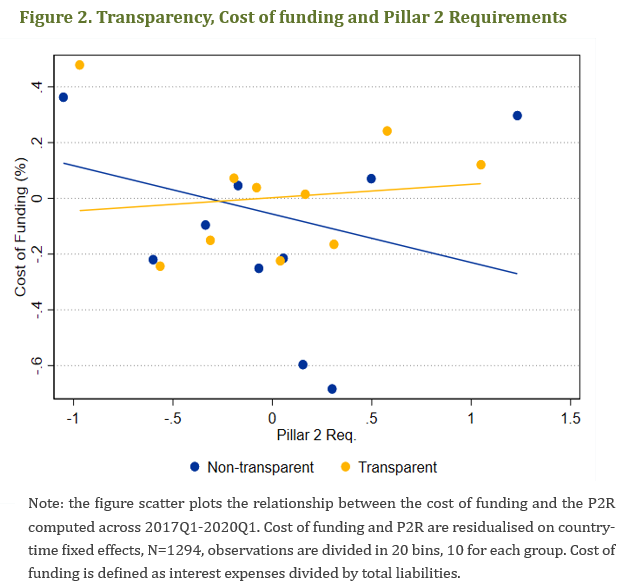

As shown in Figure 2, descriptive evidence points-out to a market failure manifesting itself in distorted pricing mechanisms. In fact, opaque banks that do not disclose their P2R, show a negative relationship between their safety and soundness proxy and the cost of funding. In other terms, in the case of imperfect information it can happen that riskier but opaque banks are rewarded by the market with lower cost of funding, they expend less resources on interest when P2R is not disclosed. This is not the case for transparent banks, which have a clear positive relationship between cost of funding and their P2R safety and soundness supervisory assessment. This market failure can be reconciled to inefficiencies arising from the asymmetric information problem which in turn fosters adverse selection when investors, or creditors, cannot fully assess the risk or quality of a bank’s assets or operations due to insufficient transparency. Our study tests empirically whether this market distortion is associated with the lack of disclosure of supervisory capital requirements.

To find an answer, we compare empirically transparent versus non-transparent banks and estimate the benefit of Pillar 2 disclosure. Our empirical design compares treated and control banks under the common trend assumption, i.e., both groups would have followed similar trends absent the treatment. Although this assumption is not directly testable, we incorporate bank-specific trends into the model as a robustness check. Including trends tied to the policy variable is a standard robustness check for the common trend assumption, Wolfers, J. (2006), Angrist and Pischke (2008).

We leverage on a detailed data collection of banks’ P2R disclosure practices to estimate whether more transparent banks benefit from a funding cost premium, and whether disclosure helps guiding markets toward improved market efficiency by reducing uncertainty on the supervisory assessment of banks. Since banks choose to disclose their P2R they could generate a bias to our estimates driven by self-selection into treatment as, more profitable, or better capitalised banks, that have a better assessment from the supervisor, could have a greater incentive to disclose their capital requirements. We run a series of tests to exclude this possibility.

We estimate that, on average, banks that disclose their supervisory capital requirements (transparent banks) experience an 11.5% reduction in funding costs compared to their opaque counterparts. This suggests that transparency provides a tangible financial benefit by lowering the perceived risk among investors and creditors. However, the effect of transparency is not uniform across all banks, indicating significant heterogeneity in its impact. Transparency enables the market to differentiate between safer and riskier banks more effectively. For instance, among banks that disclose their capital requirements, those in the safest quartile—characterized by a Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) Pillar 2 Requirement (P2R) of less than 1.5% of risk-weighted assets—experience the most pronounced advantage, enjoying a 31.1% reduction in funding costs on average. These estimates reflect the net effect of transparency, isolating its influence after adjusting for other influencing factors such as business model, country risk, or financial situation.

We describe and show how the lack of transparency surrounding P2R disclosures tends to confer an undue advantage to banks assessed by supervisors as having higher risk levels. This suggests that less transparent banks with elevated P2R values may benefit from lower funding costs due to the incomplete information created by opacity. This is a clear case of market failure that can be addressed through regulatory or supervisory intervention and improve the overall allocation of resources.

When P2R is interacted with the transparency indicator, this market inefficiency is canceled- out, resulting in improved funding allocation as transparency mitigates the issue of asymmetric information. For transparent banks, the market more accurately incorporates P2R information into funding costs, indicating that transparency enhances the alignment between funding costs and actual risk profiles. These findings highlight the role of transparency in enhancing market efficiency by reducing the adverse selection problem, as it allows safer banks to benefit from lower borrowing costs while encouraging riskier banks to improve their practices to remain competitive fostering market discipline.

Acharya, V. V., and Ryan, S. G. (2016). Banks’ financial reporting and financial system stability. Journal of Accounting Research, 54(2), 277-340.

Allen, F., and D. Gale (2000). Financial contagion. Journal of Political Economy. 108(1), 1-33.

Angrist, J. D. and Pischke, J.-S. (2008). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press

Beyer A. and Dautović, E., (2025). Bank transparency and market efficiency, ECB Working Paper Series No. 3031

Bischof, J., and Daske, H. (2013). Mandatory disclosure, voluntary disclosure, and stock market liquidity: Evidence from the EU bank stress tests. Journal of Accounting Research, 51(5), 997-1029.

Bischof, J., Laux, C., and Leuz, C. (2021). Accounting for financial stability: Bank disclosure and loss recognition in the financial crisis. Journal of Financial Economics, 141(3), 1188-1217.

Bischof, J., Foos, D., and Riepe, J. (2023). Does greater transparency discipline the loan loss provisioning of privately held banks? European Accounting Review, 1-31.

Hirshleifer, J. (1971). Suppression of inventions. Journal of Political Economy, 79(2), 382-383.

Leuz, C., and Verrecchia, R. E. (2000). The economic consequences of increased disclosure. Journal of accounting research, 91-124.

Wolfers, J. (2006). Did unilateral divorce laws raise divorce rates? a reconciliation and new results. The American Economic Review, 96(5):1802–1820

The P2R is a bank-specific capital requirement which applies in addition to the Pillar 1 capital requirement where this underestimates or does not cover business model and profitability risks, internal governance and risk management issues, capital risk, liquidity, and funding risks. In the euro area, a bank’s P2R is determined as part of the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process by the European Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), and it does not encompass the risk of excessive leverage, which is covered by the leverage ratio Pillar 2 requirement.

See ECB publication of 2024 P2Rs.