We use data on 11,233 firms across 22 emerging markets to analyze how credit constraints and low-quality firm management inhibit corporate investment in green technologies. For identification, we exploit quasi-exogenous variation in local credit conditions and in exposure to weather shocks. Our results suggest that both financial frictions and managerial constraints slow down firm investment in more energy efficient and less polluting technologies. Complementary analysis of data from the European Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (E-PRTR) corroborates some of this evidence by revealing that in areas where banks deleveraged more after the global financial crisis, industrial facilities reduced their carbon emissions by less.

In line with commitments under the Paris Agreement, many countries aim for net zero carbon emissions by 2050. This green transition will require massive corporate investments in cleaner technologies to reduce firms’ carbon footprint. Against this background, large companies like Apple, BP and British Airways have recently committed to climate neutrality. In emerging markets, some firms have started to do the same. Examples include PKN Orlen in Poland and Tesco Hungary. Unfortunately, not all companies, especially smaller ones, are able or willing to invest in cleaner technologies.

In the absence of technologies to remove carbon dioxide from the biosphere, mitigating climate change requires a drastic reduction of carbon emissions (Pacala and Socolow, 2004). This is particularly challenging for less-developed economies, which will be the source of nearly all growth in energy demand and greenhouse gas emissions over the next three decades (Wolfram, Shelef, and Gertler, 2012). It is these poorest parts of the world that are therefore in most urgent need of investments in new technologies to reduce the carbon intensity of industrial production.

In recent work, we explore how organisational constraints can hold back the green transition (De Haas, Martin, Muu ls, and Schweiger, 2021). To do so, we combine granular data on more than 11,000 firms across 22 emerging markets from the EBRD-EIB-WBG Enterprise Survey. We first show that firms differ widely in both their ability to access external funding and in the quality of their green management practices (Martin, Muûls, de Preux, and Wagner 2012). We then explore whether firms with better access to credit and those with stronger green management invest more to reduce their environmental and climate footprint. We also assess to what extent these investments indeed help firms to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

An initial analysis confirms that credit constraints correlate negatively with green investments whereas green management quality correlates positively with such investments. However, correlation does not imply causation and it is clear that past green investments may influence green management practices or credit constraints – rather than the other way around. To establish causality, we take an “instrumental variables” approach in which we use variables that affect credit constraints and green management – but not (directly) green investments or subsequent emissions. We follow two approaches here.

First, we exploit spatial variation in credit constraints across towns and cities. The supply of bank credit tightened significantly in emerging Europe after the global financial crisis, and in particular after the 2011 regulatory stress tests by the European Banking Authority (Gropp, Mosk, Ongena, and Wix, 2019). The deleveraging varied greatly across banks and therefore across localities depending on which banks operate branches where. Using data on the network of bank branches from the EBRD Banking Environment and Performance Survey II combined with bank balance sheet information from Bureau van Dijk’s Orbis, we construct local proxies for credit tightness in the direct vicinity of firms.

Second, we assume that management practices are at least partly determined by knowledge diffusion that varies from area to area. We expect, and indeed find, that managers who themselves experience extreme weather events, or are informed about such events in their region, are more likely to be concerned about climate change and the environment. They will therefore be more amenable to green management practices. Hence, exposure to weather events becomes an exogenous driver we can use to explore the causal effect of management practices on green investments.

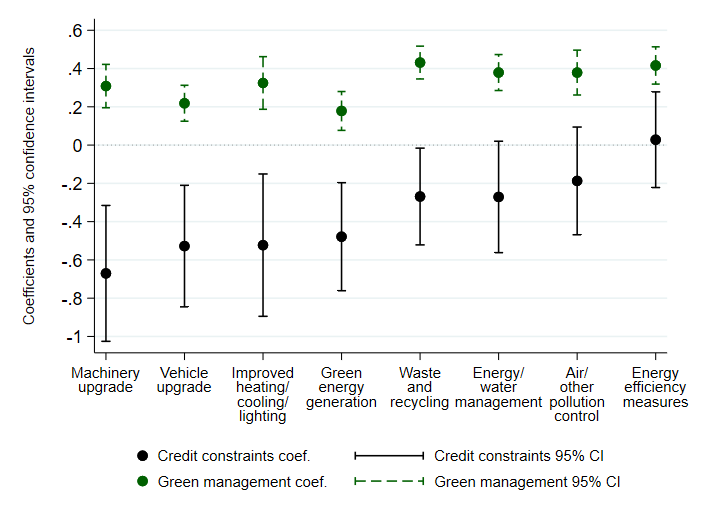

This instrumental variables approach confirms our earlier results: both credit constraints and green management significantly affect the likelihood of green investments (Figure 1). Credit constraints hinder most types of green investment, particularly those that require higher investment amounts, such as machinery and vehicle upgrades; improved heating, cooling or lighting; and green energy generation on site. They do not significantly reduce the likelihood of investing in air and other pollution control or energy efficiency measures, potentially due to the “low-hanging fruit” nature of such investments. Firms with good green management practices, on the other hand, are more likely to invest in all types of green investment, with the effect larger for those more typically thought of as green: waste and recycling; energy or water management; air and other pollution controls; and energy efficiency measures.

Figure 1. Firm-level credit constraints, green management, and green investments

Source: EBRD-EIB-WBG Enterprise Surveys, EBRD Banking Environment and Performance Survey, BvD Orbis, European Severe Weather Database, and authors’ calculations.

Note: This figure summarises the estimates of the relation between, on the one hand, firm-level credit constraints and the quality of green management and, on the other hand, firm-level green investments. Whiskers represent 95 per cent confidence intervals.

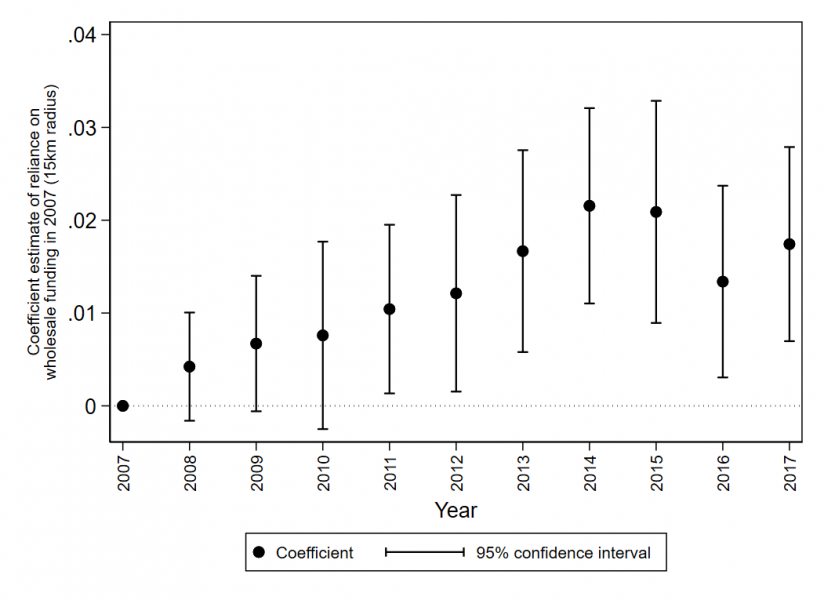

If credit constraints and weak green management prevent firms from undertaking at least some green investment projects, then one might expect that, perhaps with a lag, they can also hamper firms’ ability to reduce their emissions of air pollutants. To investigate this, we use the European Pollutant Release and Transfer Register. The E-PRTR contains data on air pollutant emissions of a large number of Eastern European industrial facilities. Our estimates indicate that although there was an overall reduction in carbon emissions and in air pollutants between 2007 and 2017, this decline was smaller in localities where banks had to deleverage more in the wake of the global financial crisis and where, as a result, firms were more likely to be credit constrained. The effects are increasingly strong from 2011 onwards signalling the potential lag between investment and its effect on emissions (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Local credit shocks and facility-level air pollution (2007-17)

Source: E-PRTR, EBRD Banking Environment and Performance Survey, BvD Orbis and authors’ calculations.

Note: This figure summarises the coefficient estimates of difference-in-difference regression to explain the impact of locality-level credit constraints on total air pollution (log kg) at the level of industrial facilities. Reliance on wholesale funding of all bank branches located in a circle with a 15km radius around the industrial facility, or, in the case of multi-facility firms, the parent company. The dots represent coefficient estimates of an interaction term between the reliance on wholesale funding in 2007 and individual year dummies during 2007-17.

Our results reveal how financial crises can slow down the process of decarbonisation of economic production, and demand caution against excessive optimism about the potential green benefits of the current economic slowdown, which – like any recession – has led to reductions in emissions. Such short-term reductions might come at the cost of longer-term increases in emissions if they are associated with more severe credit-market frictions that delay or prevent green investment. While our analysis lends support to policy measures that ease access to bank credit specifically for green investments, it also suggests that this might just be one element of a broader policy mix to stimulate such investments. Governments and development banks should also consider measures that could strengthen green management practices. This may include requirements to measure and report environmental impacts or credit lines that are contingent on the adoption of better green management practices by firms.

De Haas, R., R. Martin, M. Muûls, and H. Schweiger (2021): “Managerial and Financial Barriers to the Net-Zero Transition”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 15886, CEPR, London, BOFIT Discussion Papers, 6/2021.

Gropp, R., T. Mosk, S. Ongena, and C. Wix (2019): “Banks’ Response to Higher Capital Requirements: Evidence from a Quasi-Natural Experiment”, Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 266-299.

Martin, R., M. Muûls, L. B. de Preux, U. J. Wagner (2012): “Anatomy of a Paradox: Management Practices, Organizational Structure and Energy Efficiency”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, Vol. 63, No. 2, pp. 208-223.

Pacala, S. and R. H. Socolow (2004): “Stabilization Wedges: Solving the Climate Problem for the Next 50 Years with Current Technologies”, Science, Vol. 305, pp. 968-972.

Wolfram, C., O. Shelef, and P. Gertler (2012): “How Will Energy Demand Develop in the Developing World?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 119-138.