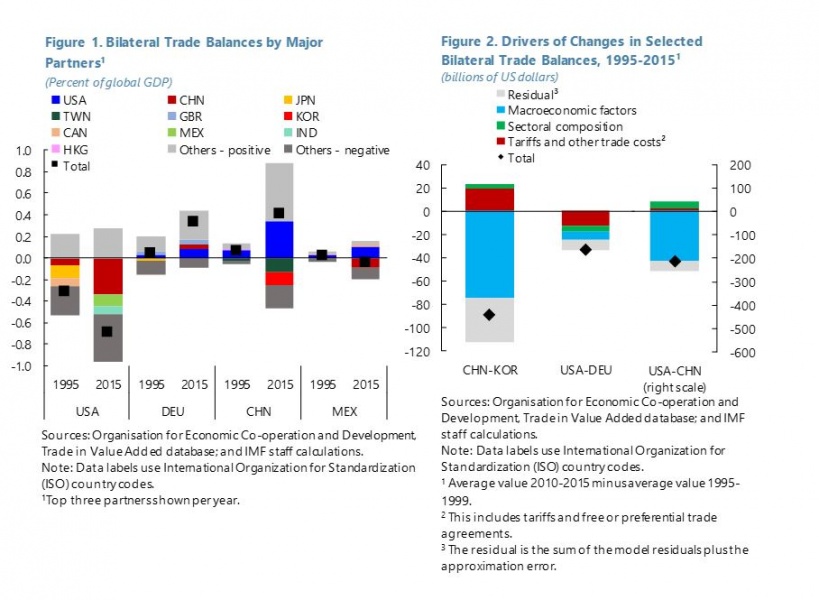

Bilateral trade balances (the difference between the values of exports and imports between two countries) have come under increased scrutiny recently. Some policymakers are concerned that their large and rising size may be the result of asymmetric obstacles to trade that distort the international trade system. But is the focus on bilateral balances the right one?

In a new study (IMF, 2019), we take a closer look at this issue and attempt to answer three questions:

• What are the main drivers of bilateral trade balances?

• What is the link between aggregate and bilateral trade balances?

• When bilateral tariffs are raised to reduce a specific bilateral trade balance, what are the effects on the countries involved and their spillover effects on third countries?

Economic forces, not tariffs, drive changes in trade balances

To examine the drivers of bilateral trade balances, we use the standard model of the trade literature, the gravity model, which explains bilateral exports. Results can also be used to explain imports and thus the bilateral trade balances. The gravity model is a useful tool because it distinguishes between three types of determinants of bilateral exports: 2

• Macroeconomic factors: Bilateral exports increase with gross output of the exporter and gross spending of the importer, scaled by world output;

• Trade costs: They can be natural (e.g., geographic proximity, common language) or trade-policy related (e.g., tariffs, free trade agreements); both bilateral and average trade costs of the importer and exporter matter; and

• Sectoral composition of supply and demand: bilateral trade increases if the sectoral structures are complementary (e.g., if the structure of exporter’s supply matches the structure of the importer’s demand). This partly captures trade that arises from the international division of production.

Our analysis shows that the evolution of bilateral trade balances over the past two decades was, to a significant extent, driven by changes in macroeconomic conditions in both trading partners. Macroeconomic factors refer to the relative movement of aggregate supply and demand in both trading partners, which also determine aggregate trade balances. Focusing for example on the U.S.-China pair (Figure 2), macroeconomic factors accounted for about 95 percent of the change in their bilateral trade balance. This reflected that:

• Aggregate supply in China was growing faster than aggregate demand; that is, a growing imbalance between supply and demand in China; and

• To a lesser extent, the fact that demand was growing faster than supply in the United States.

In contrast changes in bilateral tariffs played a smaller role over the period of analysis. This in part reflects the fact that tariffs were already low in the mid-1990s in many countries and that subsequent tariff reductions were reciprocal, with offsetting effects on bilateral trade balances.3

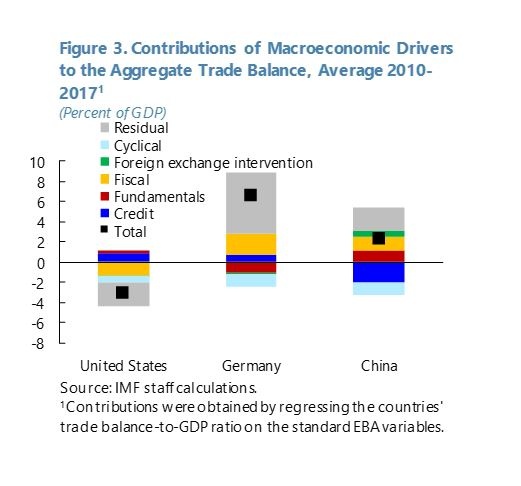

A closer look at macroeconomic factors

From a policy perspective, it is important to take a closer look at the drivers (and possible macroeconomic distortions) underlying the macroeconomic imbalance between supply and demand in each country—also reflected in their aggregate trade balance. Drivers include fundamental factors, such as demographics and the level of economic and institutional development; macroeconomic policies, in particular fiscal policy and credit cycles; and—in some cases—exchange rate policies and domestic supply-side policies (for instance, widespread subsidies to exports or to production that affect all trading partners in the same way).4 Figure 3 shows for selected large economies the contribution of some of these factors to the aggregate trade balance over 2010-17. We focus here on two examples, highlighting the role of fiscal policy in the United States and supply-side policies in China.

In the United States, the credit boom leading up to the 2008-09 global financial crisis had been an important driver of the trade deficit as it had boosted demand beyond production. While, with the crisis, financial excesses were corrected, this was offset by strongly expansionary fiscal policy following the crisis. Going forward, there is concern that the recent U.S. fiscal stimulus will lead to a further deterioration of its trade deficit. Indeed, it is boosting the economy’s demand, when demand is already strong and is likely to increase imports from all trade partners.

In China, the conventional macroeconomic factors that are at play in other economies also operate. For example, a credit boom has helped reduce the trade surplus in recent years by increasing overall demand in the economy. But China is also being discussed as one example of a country where what we call supply-side policies may have played an important role. One factor we highlight is the potential role of widespread government subsidies, in particular to state-owned enterprises. These subsidies can artificially make firms more competitive. This, in turn, can result in larger exports and trade surpluses with all partners.

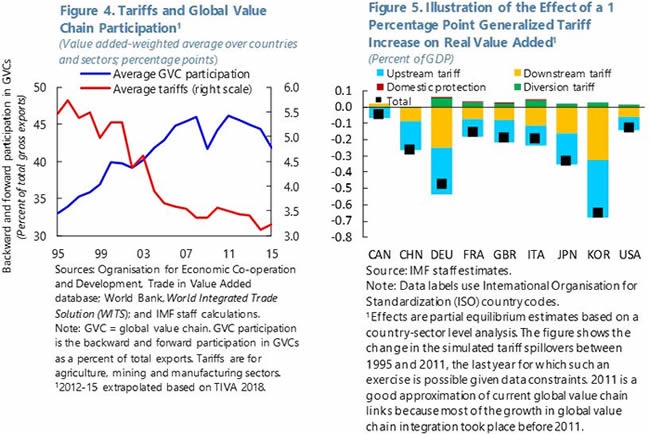

Tariffs are costly for economic activity

The analysis so far has found that the direct impact of tariffs on bilateral trade balances was small over the period of analysis. But this does not mean that tariffs do not hurt countries. Over the longer term, large and sustained declines in tariffs have shaped the international division of labor, as firms have adjusted domestic and international investment and production structures, including by organizing themselves into global value chains. The reduction in tariffs and transportation and communication costs since the mid-1990s has gone hand in hand with a significant increase in global value chain participation which—loosely speaking—is the share of exports that crosses at least two borders (Figure 4).

Increased global integration of production through global value chains creates scope for specialization and productivity improvements; but its flipside is the increased risk of international spillovers, including from increases in tariffs. A significant increase in tariffs would have ripple effects through the global value chains, amplifying the detrimental impacts on output, employment and productivity for the countries directly affected and for others upstream and downstream in the global value chain. The intuition is very simple: as firms use intermediate inputs from other sectors and countries, tariffs imposed in those sectors and countries can affect their cost of production. A tariff on imported inputs directly increases the cost of production and makes a firm less productive. To the extent that costs are passed on, such an upstream effect can also be indirect through other countries and sectors. What holds for tariffs upstream also applies to tariffs down the value chain. A firm selling intermediate goods to a country that imposes a new tariff can be affected through reduced demand from customers.

Simulations (based on country-sector estimations) illustrate that the output cost of a generalized 1 percentage point increase in manufacturing tariffs would be larger today than it would have been in the mid-1990s, particularly so for countries highly integrated in manufacturing supply chains (e.g., Korea and Germany) (Figure 5).5

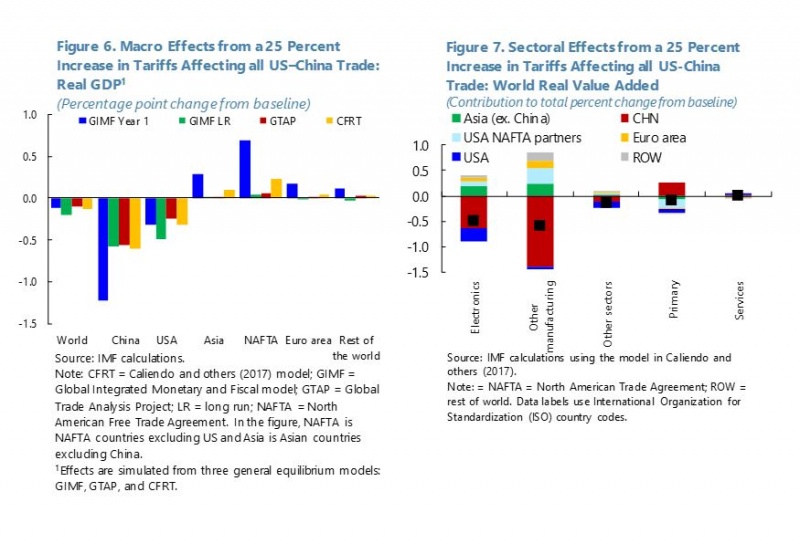

Escalation of U.S.-China trade tensions

We conclude our study by examining the effects of a potential escalation of the bilateral tariff tensions between the United States and China by assuming an illustrative increase of bilateral tariffs on all traded goods by 25 percentage points. 6 Simulations using general equilibrium models suggest three main takeaways:

• First, higher bilateral tariffs are costly for the global economy and for the economies involved, with China and the United States suffering the most (Figure 6). This results from a decrease in their external demand and a decline in returns to capital induced by tariff distortions.

• Second, bilateral tariffs do not help reduce the aggregate trade balances of the two countries, because of trade diversion. Unless macroeconomic conditions change (that is, unless the country as a whole spends less or produces more), a U.S. tariff on imports from China will just shift U.S. demand to other trade partners. Therefore, the reduction in the U.S.-China trade balance will likely be offset by changes in the U.S. bilateral trade balances with other trade partners. Mexico and Canada are set to benefit the most from trade diversion, reflecting their close proximity to and strong trade relations with the United States; east Asia would also benefit to some extent. Bilateral tariffs are thus not only costly for the countries involved but they are also likely to be ineffective in addressing external imbalances.

• Finally, higher bilateral tariffs would lead to significant sectoral reallocations as GVCs are repositioned (Figure 7). In particular, over the long term, there would be sizable shifts in manufacturing capacity away from China (and the United States) toward Mexico, Canada and east Asia. These sectoral shifts would imply sizable job losses in specific sectors, especially in the United States (agriculture, transport equipment) and China (electronics, the “other manufacturing” sector).

Conclusion

Two main policy conclusions emerge from our analysis. First, the discussion of external imbalances is rightly focused on aggregate trade balances and current accounts—as well as the macroeconomic policies and distortions driving them. Unless macroeconomic conditions change, using bilateral tariffs to target a specific bilateral trade balance is likely to lead to compensating adjustments in other bilateral trade balances due to trade diversion, leaving the aggregate trade balance broadly unchanged. Second, further multilateral reductions of tariffs and non-tariff barriers would benefit the global economy, by boosting trade and leading to further gains in output, employment and productivity. But while our findings suggest lower barriers to trade would benefit macroeconomic outcomes, there are valid concerns about the distributional effects of trade. It is therefore important to have policies in place to ensure that the benefits from trade are widely shared and that those affected are adequately protected.

International Monetary Fund, 2019. “The Drivers of Bilateral Trade and The Spillovers from Tariffs” in World Economic Outlook, Chapter 4. April 2019.

The gravity model is estimated at the sector level, with 63 countries and 34 sectors over 1995-2015.

See IMF (2019).