Building back better by going green and digital is the way out of the Covid-19 crisis in Europe. Next Generation EU supports this twin transition. However, these are among the most knowledge-intensive and innovation-driven sectors, which require not only massive investment but also high-quality institutions. Moreover, the twin transition will also require a larger pool of high-skill labour more evenly distributed among member states. Thus, the quality of private and public institutions and labour skills need to be improved and made more even among member states to arrest the tendency of divergence in the European Union.

The Covid-19 crisis is posing the biggest challenge ever to the European Union, both economically and socially. An important characteristic of such big crises is that they tend to accelerate already existing trends in an economy. Moreover, this crisis also made a uniquely positive impact by focusing the minds of political leaders on overcoming the crisis by pushing forward with the key policy priorities laid out by the new European Commission just before the pandemic started. That is, to go green and digital, which requires massive public and private investments. The crisis made it also imperative to arrest the trend of divergence in the Union and to address the major differences among member states regarding their fiscal capacities to undertake the necessary public investment (Buti and Papacostantinou, 2021).

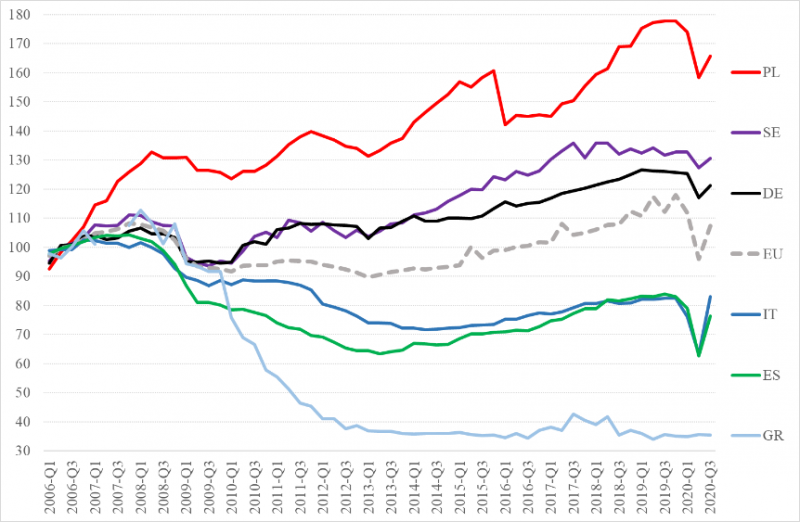

In the aftermath of the 2008-2013 crisis, the Union had one of the longest periods of uninterrupted recovery. Nevertheless, divergence remained a main characteristic of post-crisis development. As recalled in Buti (2020), amongst the large Eurozone members, Germany and Italy are at the two ends of the spectrum: between 2008 and 2021, the gap between the two countries amounted to some 20 points of GDP (+12 for Germany, -8 for Italy). This divergence was most important in investment (Figure 1). Settling on such divergent paths of investment determines the growth potentials of member states to a large extent.

Figure 1. Divergence in investment in the European Union following the 2008-13 crisis.

Sources: The authors’ own calculations based on data from Eurostat.

Notes: Gross fixed capital formation. Quarterly data, volume indices, the average for 2006=100. Seasonally and calendar-adjusted data.

With a major divergence also in the fiscal space of member states, when the Covid-crisis hit the European economy, it was essential to create a joint EU-level facility that provides support where it is most needed and focuses on investment. This way, it can help restore the growth potential and promote the twin transition, while helping to arrest the tendency of divergence within the Union. The Next Generation EU, particularly the Recovery and Resilience Facility, intends to serve all these important goals.

The Recovery and Resilience Programmes will have to devote 37% of the resources to the green transition and 20% to the digital transition. Their implementation will be based on a combination of investment projects and reforms since, to remove growth bottlenecks, it is necessary to provide the necessary resources and review the rules of the game.

If the Next Generation EU is successful in accelerating the shift towards a green and digital economy, this will also entail a major expansion of knowledge-based and innovation-driven sectors and activities. Such activities are highly dependent on institutional quality and human capital, more so than other activities. We turn to these two aspects now.

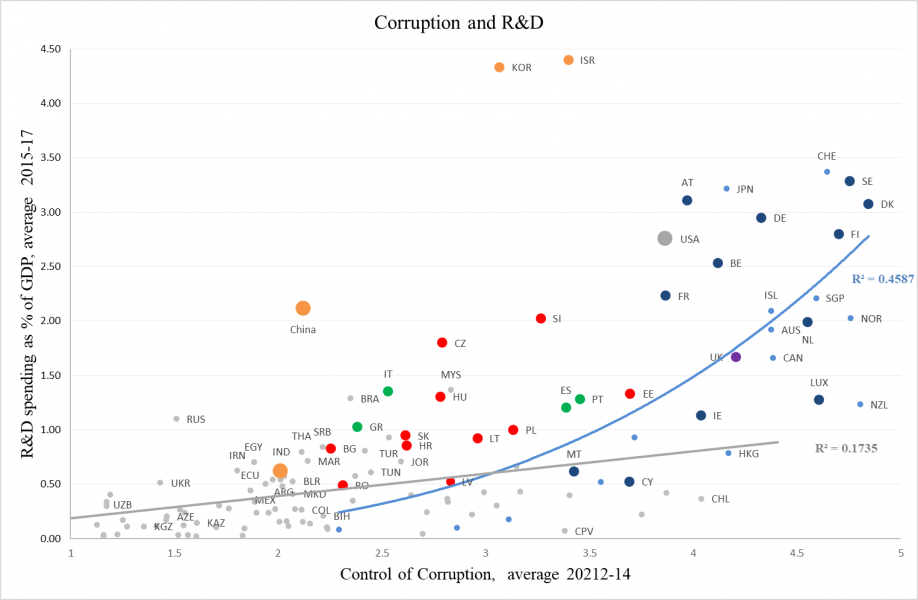

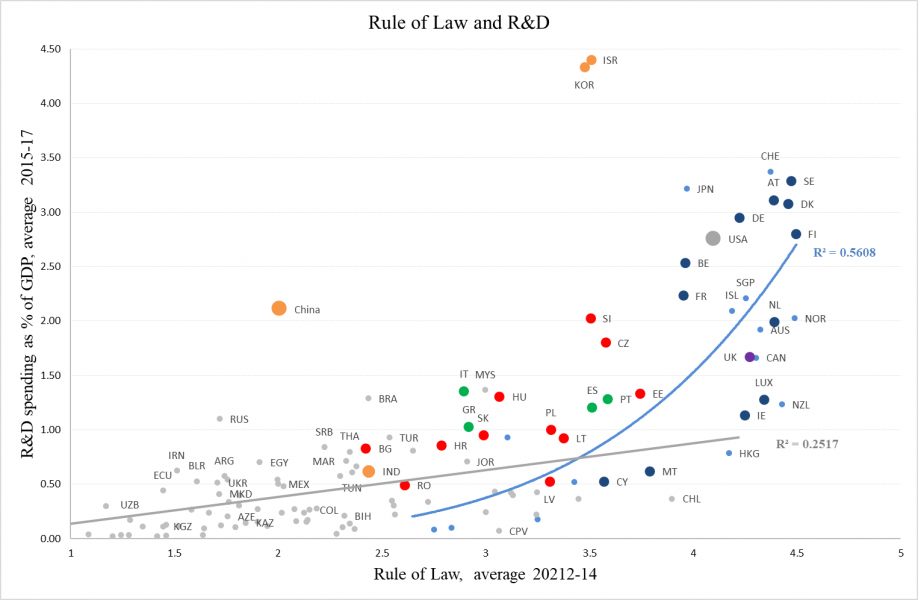

Institutional quality is a major driver of development (North, 1990, Acemoglu et al., 2005). This is particularly true for countries with knowledge-based and innovation-driven economies. In Figure 2, we capture institutional quality by the control of corruption and respect of the rule of law.

Figure 2. Impact of corruption control and rule of law on R&D at different development levels

|

|

Source: Székely, 2020, the author’s own calculations based on data from the World Bank.

Notes: Based on the corresponding WGI sub-indices, both calculated as averages for 2012-14 and increased by 2.5 to make observations non-negative. Trend lines in gray are for the bottom four quintiles of countries by per capita GDP in PPP, averaged for 2015-17, observations in grey. Trend lines in dark blue are for the upper quintile countries, observations in light blue. Observations in dark blue are EU countries. Southern European EU countries are in green, EU11 are in red.

As both charts above suggest, the relationship between institutional quality and R&D intensity is relatively week and seems linear for the bottom for quintiles of countries based on per capita GDP. However, for the highest quintile, for the most developed countries in the world, it becomes much stronger. The figure suggests that the nature of the relationship between the quality of institutions and the relative size of research and development in an economy is turning highly nonlinear as countries move towards a knowledge-based, innovation driven activities. This may well reflect the increasing importance of allocative efficiency as an economy approaches the frontier of economic development (Acemoglu et al., 2006). Many EU countries in Western and Northern Europe belong to this group, and several others in Southern and Central Eastern Europe have or are about to enter the transition towards this phase of development.

These charts show correlation, causality may well run in both directions and there may be common causes driving both factors, quality of institution and innovation. Nevertheless, if one observes a deterioration of institutional quality in a country, as it happened, for example, in the Southern European EU member states in the past decades (Székely and Kuenzel, 2021), it is unlikely that such a country will be able to attract knowledge-based and innovation-driven activities and firms.

In similarly large economic areas as the EU but with lower levels of overall development, such as China, the locational choices of companies for their R&D intensive activities inside the area are also greatly influenced by the quality of institutions (Zhou, 2014). This suggests that is the nature of the activity that requires a location with good institutions, even at a lower level of overall development. The role of differences in institutional quality is also an important factor that drives divergence among the development of regions within countries, even for the most developed countries (Charronet al., 2014).

Success with moving towards a green and digital economy will also critically depend on the availability of high-skilled people who can help companies adopt the new technologies and business models such twin transition requires. There are pronounced differences among EU countries in this regard too, which already influence the location of high value-added economic activities in the EU. This impact is likely to increase further.

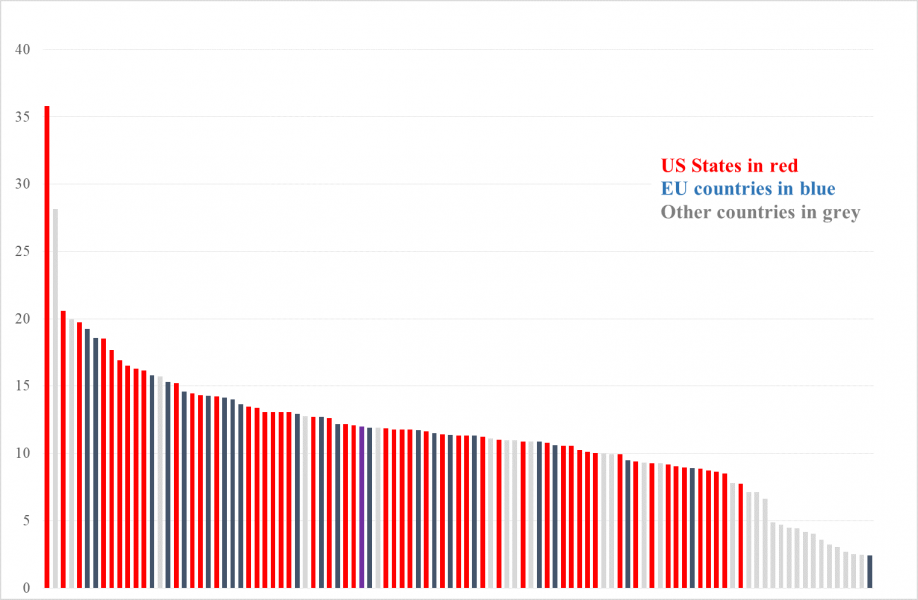

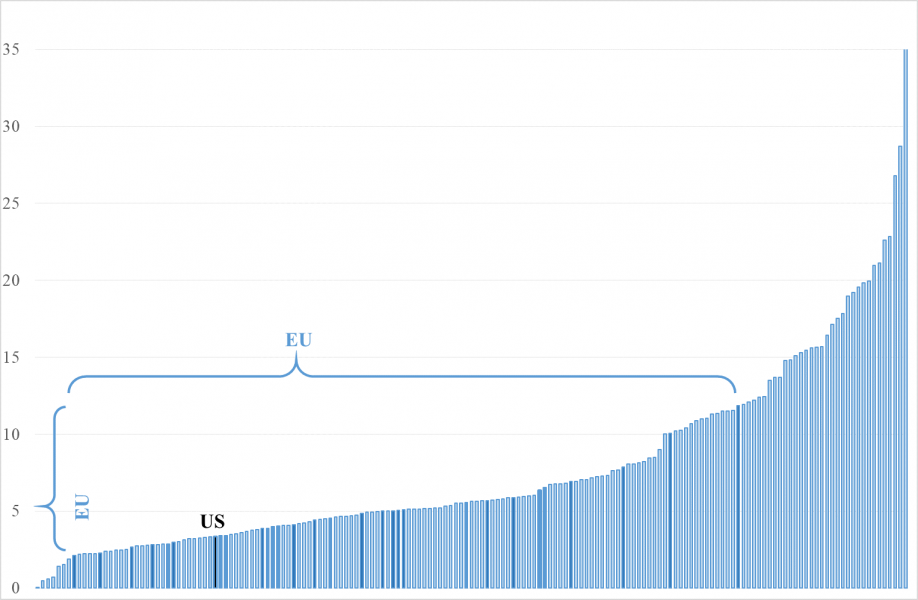

Figure 3. Share of people with at least a master degree in the total population of 25+, 2017.

Sources: World Bank, World Development Indicators and US Census Bureau, American Community Survey (ACS).

Note: Data for US states are centered 5-year averages for 2017 (2015-19). In calculating the ranges for the US and EU shown in the chart, the averages are taken for the top and bottom three countries.

As Figure 3 shows, there is a similar dispersion among US states regarding the share of high-skill people in the total population, albeit perhaps less so at the lower end. With a stronger fiscal capacity at the central level, particularly a federal social security system, the US is perhaps better equipped to deal with the consequences of such dispersion among its member states.

The capacities of EU member states to employ fully their high-skill people also differ significantly (Figure 4). These differences are also very likely to be closely related to institutional weaknesses that tend to keep away firms in knowledge-intensive sectors. Hence, with an increasing demand for high-skill labour stemming from the twin transition, and given the overwhelming need to arrest divergence, reforms that reduce such differences are paramount.

Figure 4. Unemployment rate among people with an advanced degree, 2000-2018 averages.

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators.

Note: The columns for the EU countries are shaded in dark blue, for the US in black.

Accelerating concentration of high value-added activities among and within EU member states, driven by locational choices of firms in dynamic innovative industries also shifts the tax base in a major way. While within countries, national fiscal systems can mitigate the consequences of such trend to some extent, even at the national level a major acceleration of such trend can pose difficult challenges. However, as there is still a very limited fiscal capacity at the European level, mitigating the negative side effects of strengthening divergence would be a much more difficult task for the EU as a whole. As the experience of the EU’s eastern enlargement suggests, the asymmetries of a rapid, market-driven economic integration can pose major policy challenges even in highly successful countries (Buti and Székely, 2019).

With digitalization and a possibly increasing role of teleworking because of the pandemic, mostly high-skill employees will also enjoy more choices regarding where they live. So far, this has been mostly driven by the locational choices of firms (and government institutions). However, these new post-Covid trends can add the locational choices of individuals who are teleworking as a new factor driving agglomeration.

This can further accelerate divergence, possibly more so within countries. The concentration of high-skilled people in the EU is rather high and it has been increasing in the past decades (Székely, 2020). The quality of institutions appears to be a major factor in this regard too, albeit perhaps other aspects of institutional quality, such as the quality of public services, education or health care, play an important role. Therefore, the quality of institutions and the quality of human capital is likely to reinforce each other in the impact on innovation activities, in a vicious or virtuous cycle.

It will be critical for EU member states to improve the overall level of institutional quality and reduce unevenness among countries and regions in this regard. The Recovery and Resilience Facility is designed to give a major impetus to growth-enhancing reforms and improvements in institutional quality. While this is a major step in the right direction, with the twin transition taking off, more may be needed particularly regarding efforts to make institutional quality more even and thus promote convergence among countries and regions, and to reduce path dependence of developments.

The strategy of going green and digital, if successful, will no doubt lift the growth potential of the EU also by increasing the share of knowledge-intensive and innovation-driven sectors and activities. However, on the other hand, this will further strengthen the already strong agglomeration trends in the EU as such sectors and activities tend to be much more concentrated than economic activities in general, among countries, and among regions within countries. Moreover, research suggests that differences in institutional quality among countries and among regions within countries are a major factor driving such agglomeration. This characterizes development globally and the EU is no exception in this regard.

The EU has been very successful in promoting trade and FDI, which are important drivers of development. However, it has been much less successful in accelerating institutional development in its member states in the past decades (Székely and Kuenzel, 2021). Without improvements on this front, promoting green and digital transition will hit a barrier, and may further aggravate potentially harmful divergence within the Union.

Recognizing the importance of institutional quality and the weaknesses of the institutional channel in the EU, the Recovery and Resilience Facility not only supports investment to a significant extent, but puts equal emphasis on promoting critical reforms and, through this, better institutions. Focusing on investment that supports green and digital transition will help accelerate growth by enhancing productivity and environmental sustainability. Flanking reforms can help distribute the benefits of this more equally among countries and regions within the EU, thus enhancing coherence. In turn, faster growth with enhanced coherence will make development socially more sustainable. Good implementation is the key to success in this regard, which, if happens, will make the European project more sustainable, economically, socially, and politically.

Acemoglu, D., Aghion, P. and Zilibotti, F., 2006. Distance to frontier, selection, and economic growth. Journal of the European Economic Association 1: 37–74.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S. and Robinson, J.A. (2005) Institutions as a fundamental cause of growth. In P. Aghion and S.N. Durlauf (eds.), Handbook of Economic Growth, Vol. 1a (pp. 386–454). New York, NY: North-Holland.

Buti, M., 2020. A tale two crises: Lessons from the financial crisis to prevent the Great Fragmentation, VoxEu.org (CEPR), 13 July 2020.

Buti, M. and G. Papacostantinou, 2021. The legacy of the pandemic: how COVID-19 is reshaping economic policy in the EU, (CEPR), Policy Insight, 109, April.

Buti, M. and I.P. Székely, 2019. Trade shocks, growth and resilience: Eastern Europe’s adjustment tale, VoxEu.org (CEPR), 28 June 2019.

Charron, N. Dijkstra, L. and Lapuente, V., 2014. Regional Governance Matters: Quality of Government within European Union Member States, Regional Studies, 48:1, 68-90,

North, D. C., 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Székely, I. P., 2020. The knowledge channel and the EU. University of Colorado, Boulder, CEUCE, May 2020, mimeo.

Székely, I. P. and Kuenzel, R., 2021. Convergence of the EU member states in Central-Eastern and South Eastern Europe: a framework for convergence inside a close regional cooperation. In: Landesmann, M. and Székely, I. P. (eds), 2021. Does EU membership facilitate convergence? The experience of the EU’s eastern enlargement. Volume I, Palgrave-Macmillan, pp. 27-87.

Zhou, Y., 2014. Role of Institutional Quality in Determining the R&D Investment of Chinese Firms. China &World Economy, 22 (4), 60–82.