Introduction

Following the financial crisis of 2008, there has been a wave of regulatory reforms aiming to address the weaknesses in the financial system.1 A lot has been achieved since then. Basel III has updated its Basel II standards in two major waves of reviews. In the first wave, regulation has incorporated a systemic perspective to capital, adding liquidity, leverage and interest rate risks requirements to the mix2, while in the second wave it revised its current approach to risk management in the areas of credit risk, market risk, Counterparty Credit Risk, Credit Valuation Adjustments (CVA) and operational risk.3

All these initiatives were necessary to reduce the risks in the system and the regulation became more robust, broader in scope, and more forward-looking. It became more robust because of initiatives to improve the quantity and quality of capital, revisions to credit and counterparty risk, market risk, CVA and operational risk management to improve risk sensitivity, as well as the setting up of a backstop measure to undue variability of prudential outcomes in the form of a revised output floor. The regulation also expanded its scope of risks coverage, now encompassing areas such as leverage and liquidity, in addition to risk-based capital. Finally, the regulation became more forward-looking, taking into account aspects such as systemic risk, countercyclical buffers and other macroprudential measures and finally resolution regimes.

Financial regulation however also became more complex. Trying to reflect a quite exhaustive set of risks and keeping risk sensitivity as a very desirable target line led us to design lengthy pieces of regulation. Until now we were asking ourselves the question: Did we get it right ? Will it be enough? It may be time to step back and ask ourselves the questions: Do we have a fitted suite of tools and ability to do a smart supervision ? Is it proportionate?

To build appropriate safeguards, we need to reject complexity. Complexity comes with more abstruse rules and less capability to supervise their implementation. Complexity leads to more data, but also less ability to process and interpret it. As a result regulation seems to be in a perpetual catch-up game with the banks and their business models.

A good part of the complexity comes from the continuous adaptation of the banking sector once rules are implemented. Not only banking activities and innovation are part of the financial industry developments, but, as soon as a rule, simple or complex, becomes a binding financial regulation, it will cause changes in financial institutions’ risk management that will make it less binding and less effective.4 For example, as a response to the new regulatory context after the crisis, banks adapted their business strategies and balance sheet structures to comply with the new rules while focusing on recovering profitability.5

At the same time, while simple rules may seem appealing, they are not the solution, as they risk to water down institutions’ capacity to absorb losses or face liquidity shocks. One way of simplifying the rules without undermining the fundamental prudential safeguards is to continuously monitor the balance among ruling, disclosing and supervising. The revision of this balance led to create more conservative buffers while at the same time improving public disclosure (to counteract the reduced sensitivity to risk), narrowing the range of modelling choices, and further harmonising supervisory practices with respect to model approvals.

Striking the right balance between simplicity and complexity is key. In suing the approaches and allocating roles to rules, disclosure, and supervision, a good deal of the solution is to foresee the incorporation of proportionality.

Beyond the long standing legal requirement that regulatory powers should be proportionate to their goals, proportionality in modern prudential banking frameworks is the principle of tailoring regulatory requirements to different groups of banks. The discussion about applying a proportional approach to banking regulation is not new. Several jurisdictions outside the EU have implemented specific regulatory standards for smaller and less complex banks.6 Since the introduction of risk-based supervision, the principle of proportionality has played an established role in the EU day-to-day bank supervision too.7 The main goal of a proportionality regime is to tackle the complexity of rules.

One approach is to have a one-size fits-all rule, when the rules are the same for all the banks. This approach was taken in Basel I, which, historically, has been designed having in mind the traditional model of banking, whereby the bank serves as the intermediary between depositors and borrowers. This baseline business model is the cornerstone of the definition of credit institutions according to the Capital Requirements Regulation in Europe8. However, this definition has evolved to include more complex activities and interactions with the financial markets, hedge funds, insurance sector, etc. These changes in the range of services provided were facilitated by the wave of accelerated financial innovation, which has allowed banks to follow different approaches to fund their balance sheets and to take on different type of risks.9

These new complexities were reflected in Basel II and III, which follow a risk-based approach, whereby each banks needs to comply to a tailored set of rules based on its specific balance sheet and risks. This includes risk specific thresholds, waivers etc. As a result, a specific concept of bank business model – defined as the mix and share of risks taken by a bank – is incorporated into the regulation, through the means of activity or threshold based requirements. This approach has also been extended to the supervision on a day-to day basis.10

Treating each bank as a unique business model may be feasible for a supervisor who is in close contact with the institution in the context of its supervision activity, but is not practical when conducting an analysis at a European level and assessing the impact of European regulation. In this case, a peer group for comparison brings a more efficient way of understanding the data.

Therefore, a middle ground between the one-size-fits all and unique business models needs to be found – a proportionate approach, which identifies groups of banks to which different rules may apply. The key feature of such a proportionality regime is the criteria used to identify the banks to which a proportional framework is applied. The criteria for identification/ segmentation vary widely across jurisdictions, although a bank’s size plays a major role. In addition to size, the bank’s business model and business activities are critical considerations when applying a proportional regulatory treatment.

There are several proportionate approaches based on the criteria used to identify the groups of banks to which different rules apply.

One approach is the tiered banking sector. This approach groups banks in tiers depending on their size and systemic nature. In the USA for example, the regulatory agencies are taking a tiered approach to banking supervision and regulation. Institutions are broadly categorized based on their size (assets held), complexity and “level of risk they pose to the overall financial system” which dictates the level of regulation and oversight for each tier.

The tiered approach aims to reduce the regulatory burden on smaller and less complex banks. Over the past seven years, regulators have published multiple rules and regulations for the banking industry. Staying abreast of these rules and complying with them can be a significant financial burden to banks, particularly smaller ones.11

On the other hand, the fact that regulation is increasingly geared to size imposes a progressive growth tax on banks and affect almost every operational and strategic decision that banks make going forward. In contradiction with the free movement of capital and single market objective for Europe it tends to freeze market shares and capital allocation by region. If regulation continues to escalate in this regard, banks will have to weigh the financial benefits of growth against the cost and limitation of regulation.

In addition, size-related thresholds alone do not capture the full extent of banks’ business models and related risks.12 Small institutions typically run less diversified business models and are therefore more exposed to adverse developments in specific regions or economic sectors. In the recent past for example, there were crisis as a consequence of simultaneous failure of several small and medium-sized institutions running similar business models, which are jointly exposed to the same type of shock.

Another proportionate regime could be based on a business model classification. A business model classification groups banks according to a set of information such as balance sheet structure, customer base, branch network etc. Each group of business models should be exposed to roughly similar risks.

The identification of business models emerges as an important task for regulators and supervisors as opposed to a tiered approach for three reasons:13

However, despite the requirement for EU supervisors to assess the business models of the supervised banks, there are no common business model definitions and categories across the EU for regulatory purposes. Business model analysis (BMA) within the current supervisory review and evaluation of banks, because of its focus on the identification of each bank’s business and strategic risks and the assessment of the institution’s business model viability, does not provide a classification of banks by business model that is readily available and easily usable for analysis of trends and risks at macro level and regulatory impact assessment.

The academic literature also attempted to classify banks by business model. The studies in the area of business model classification focus on quantitative approaches, based on clustering methodologies applied to the financial accounts of banks. This approach is rigorous because it reflects the balance sheet structure of the banks. However, missing any qualitative assessment, it allows only three to five very broad categories of universal, retail and wholesale banks to be distinguished, without further granularity with respect to specialised business models such as mortgage banks or public development banks. Moreover, the existing studies use data at consolidated level, which means that data for many individual institutions within the same banking group, which probably follow different business models, is aggregated and disregarded. The application of such a classification for policy purposes is limited by lack of granularity and lack of identification of specialised business models.

Until today, there is no common and objective approach to business model classification. Agreeing on such a classification would be the first step to creating a proportionate approach taking into account various business models in the EU. EBA has done a first step in this direction by conducting a survey of EU business models, but more work is required to agree on a common approach that is consistent across time and regularly updated given the changing landscape of the EU banking sector.16

Diversity in business models presents many potential advantages for the financial sector and the economy as a whole. To indicate a few, it may lead to reduced vulnerability to crisis due to diversification of risks across the financial sector. Additionally, it also means more choice for customers as a more refined range of financial products are available. However, diverse business models can also create more challenges for regulators and supervisors, as they generally entail -different degrees of riskiness and/or may lead to different responses to regulation. This has been observed during the 2008 financial crisis, where certain specific business models were more vulnerable to the shocks of the crisis, such as reduction in wholesale funding or high losses on loans backed by real estate.17 Hence monitoring different business models is important.

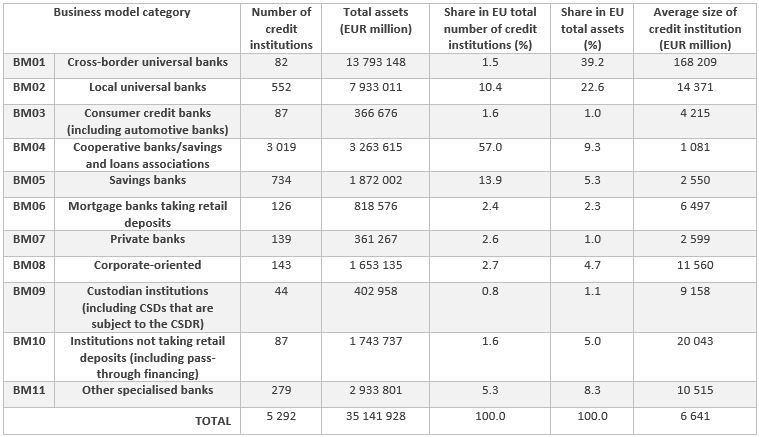

In 2016, the EBA conducted a survey of all the institutions at solo level in the EU, to get a snapshot of the landscape of business models in the EU banking sector.18 The results showed that the credit institutions in the EU represent a heterogeneous group with various business model categories. Referring to the 11 business model categories described in Table 1 below, 57 % are classified as cooperative banks and savings and loans associations. The next biggest categories in terms of number are savings banks (14 % of credit institutions) and local universal banks (10 %).

Table 1. Bank business models in the EU (as of December 2015)

Note: The data for banks in the table is presented at solo level.

Source: Cernov and Urbano (2018), Identification of EU Bank Business Models: A Novel Approach to Classifying Banks in the EU Regulatory Framework, EU Staff Papers No. 2.

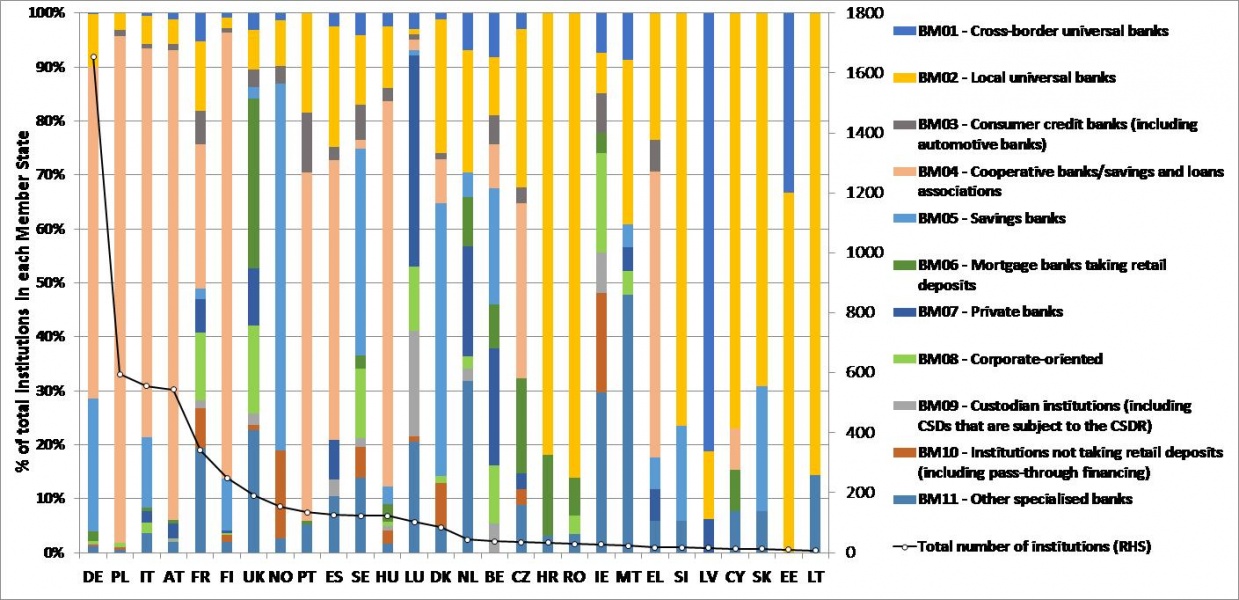

The distributions of the number of institutions per business model varies from country to country. Based on the dominant type of institutions, four major groups of countries are distinguished. Countries in the first group, comprising Germany, Greece, Spain, Italy, Hungary, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Finland, have more than 50 % of their institutions assigned to the business model cooperative banks and savings and loans associations. The second group of countries – Estonia, Croatia, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovenia and Slovakia – are dominated by local universal banks or cross-border universal banks (more than 50 % of institutions). The third group of countries – Denmark and Norway – have a majority of institutions (more than 50 %) assigned to savings banks. Lastly, Belgium, Czech Republic, Ireland, France, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Sweden and United Kingdom have more diversity in the institutions’ business models without any specific business model outnumbering the others.

Figure 1. Number of financial institutions in the EU by business model

Note: The data for banks in the table is presented at solo level.The primary axis shows the percentage of each business model in total number of institutions in each country. The secondary axis shows the total number of institutions in each country. Notations: RHS – right-hand side axis.

Source: Cernov and Urbano (2018), Identification of EU Bank Business Models: A Novel Approach to Classifying Banks in the EU Regulatory Framework, EU Staff Papers No. 2.

Finally, in the context of business models it is worth mentioning the upsurge of “fintech”. Based on the EBA”s observations, published in a recent report that assesses the impact of “fintech” on incumbent credit institutions” business models, incumbents are categorised into (i) proactive/front-runners, (ii) reactive and (iii) passive in terms of the level of adoption of innovative technologies and overall engagement with “fintech”. Potential risks may arise both for incumbents not able to react adequately and timely, remaining passive observers, but also for aggressive front-runners that alter their business models without a clear strategic objective in mind, backed by appropriate governance, operational and technical changes.19

The rise of “fintech”, use of apps on smartphones to innovate in financial services such as payments, might shift the nature of risk and require a new arsenal of macroprudential instruments. The business model classification should take into account this new dimension of bank business model and capture it in the regulation of its risks.In this regard, Basel also encouraged extending the scope of macroprudential regulation to include fintech, among other entities.20

Following the financial crisis of 2008, there has been a wave of regulatory reforms aiming to address the weaknesses in the financial system. A lot has been achieved since then. Overall, regulation became more robust, broader in scope, and more forward-looking. Financial regulation however also became more complex.

To build appropriate safeguards for good supervision, we need to reject complexity. However complexity should be reduced without undermining the fundamental prudential safeguards. Usually this means requiring more conservative buffers and capital requirements, to ensure the proper coverage of the risks for all types of banks. Such an approach may lead to less risk sensitivity. Striking the right balance between simplicity and complexity is key, and using business models should certainly be part of the solution.

In this context, the identification of business models emerges as an important task for regulators and supervisors for three reasons:

Until today, there is no common and objective approach to business model classification. Agreeing on such a classification would be the first step to creating a proportionate approach taking into account various business models in the EU. EBA has done a first step in this direction by conducting a survey of EU business models, but more work is required to agree on a common approach that is consistent across time and regularly updated given the changing landscape of the EU banking sector.

Liikanen, Erkki, High-level Expert Group on reforming the structure of the EU banking sector (2012), Final Report, Brussels, 2 October.

Basel (Rev June 2011), Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems; Basel (Oct 2014), Net Stable Funding Ratio; Basel (Jan 2013), Liquidity Coverage Ratio.

Basel (Dec 2017), Basel III: Finalising post-crisis reforms. Basel (Jan 2016), Minimum capital requirements for market risk. A final revised standards for market risk are expected to be published in January 2019.

Speech by Jaime Caruana, General manager, BIS, Promontory Annual Lecture, 4 June 2014. Accessed at: https://www.bis.org/speeches/sp140604.pdf

Ayadi, Rym, Emrah Arbak and Willem Pieter De Groen (2011), Business Models in European Banking: A Pre- and Post-crisis Screening, CEPS Paperbacks.

Basel (Aug 2017), “Proportionality in banking regulation: a cross-country comparison”. Accessed at: https://www.bis.org/fsi/publ/insights1.pdf

See EBA SREP Guidelines https://eba.europa.eu/-/eba-publishes-final-guidance-to-strengthen-the-pillar-2-framework

Regulation (EU) Nº 575/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on prudential requirments for credit institutions and investment firms.

Ayadi, Rym, Emrah Arbak and Willem Pieter De Groen (2011), Business Models in European Banking: A Pre- and Post-crisis Screening, CEPS Paperbacks; Ayadi, Rym, Willem Pieter De Groen, Ibtihel Sassi, Walid Athlouthi, Harol Rey and Olivier Aubry (2016), Banking Business Models Monitor 2015: Europe, HEC Montréal, International Research Centre on Cooperative Finance.

In the USA, the goal of the tiered approach is to provide community banks, which represent over 85% of banks in the US, some regulatory relief.

Cernov and Urbano (2018), Identification of EU Bank Business Models: A Novel Approach to Classifying Banks in the EU Regulatory Framework, EBA Staff Paper No. 2. Accessed at:

https://www.eba.europa.eu/documents/10180/2259345/Identification+of+EU+bank+business+models+-+Marina+Cernov%2C%20Teresa+Urbano+-+June+2018.pdf/8a69aed9-3e58-4f81-bc4c-80a48e4c3779

Mergaerts and Vennet (2015), Business models and bank performance: A long-term perspective. Accessed at: https://www.eba.europa.eu/documents/10180/1018121/Mergaerts%2C%20Vander+Vennet+-+Business+models+and+bank+performance.+A+long+term+perspective+-+Paper.pdf

See more details in Liikanen, Erkki, High-level Expert Group on reforming the structure of the EU banking sector (2012), Final Report, Brussels, 2 October.

Liikanen, Erkki, High-level Expert Group on reforming the structure of the EU banking sector (2012), Final Report, Brussels, 2 October, provides a detailed account of business models that were most affected by the crisis.

EBA (2018), EBA Report on the Impact of Fintech on Incumbent Credit Institutions’ Business Models, accessed at: https://www.eba.europa.eu/documents/10180/2270909/Report+on+the+impact+of+Fintech+on+incumbent+credit+institutions%27%20business+models.pdf.

Cernov and Urbano (2018), Identification of EU Bank Business Models: A Novel Approach to Classifying Banks in the EU Regulatory Framework, EBA Staff Paper No. 2. Accessed at: https://www.eba.europa.eu/documents/10180/2259345/Identification+of+EU+bank+business+models+-+Marina+Cernov% 2C%20Teresa+Urbano+-+June+2018.pdf/8a69aed9-3e58-4f81-bc4c-80a48e4c3779

Cernov and Urbano (2018), Identification of EU Bank Business Models: A Novel Approach to Classifying Banks in the EU Regulatory Framework, EU Staff Papers No. 2.