This note presents the key findings of the publication “Business resilience in the pandemic and beyond: Adaptation, innovation, financing and climate action from Eastern Europe to Central Asia,” based on the latest wave of the EBRD-EIB-WBG Enterprise Survey (Enterprise Survey 2019). The report discusses the structural challenges of the private sector in the region and examines how firms adapted to the pandemic crisis, making use of the COVID-19 Follow-up Enterprise Surveys. The resilience of firms to the pandemic and their adaptation capacity are a testament to the importance of productivity gains, innovativeness, managerial quality, global integration and financial lifelines provided by banks or corporate groups. Government support measures played a crucial role by reducing the stress on vulnerable firms and enhancing survival. More structurally, trade integration with developed economies, access to information and know-how through participation in global value chains, the use of foreign licensed technology and modern management practices all contribute to higher rates of innovation. Firms are more likely to invest in a greater number of green measures if they experience fewer financial constraints and have better green management practices. Firms continue to rely largely on bank credit, while many remain either financially autarkic or credit-constrained. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and young firms see access to loans or other finance as a significant problem, particularly young and innovative SMEs.

As well as a terrible cost in human lives, the war in Ukraine will have far-reaching economic consequences across Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Beyond the direct effect of the massive losses in Ukraine and unfolding sanctions in Russia, the global equilibrium is being impacted by the dramatic change in the geopolitical context, concerns for energy and food security, and as a persistent energy shock that has revealed underlying structural vulnerabilities. Disruptions to trade and financial flows, and tourism and remittances, as well as persistent uncertainty, add to pre-existing vulnerabilities, testing economic and business resilience once again. Against this backdrop, a structural understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of businesses across the region, the challenges they face and their ability to adapt in the face of dramatic shocks is crucial.

The war started as the region’s businesses were recovering from the pandemic. Business resilience in the pandemic and beyond asks how firms in the region were able to survive the sharp downturn, how prepared they are to face future challenges, such as digitalisation, shifting global value chains and global warming, and whether gaps in access to finance are likely to impair short-term resilience and long-term prospects. It points to the relevance of structural features as a driver for regional growth and firms’ resilience and adaptation.

Business resilience in the pandemic and beyond is a joint report from the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), with contributions from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). It uses a unique firm-level dataset, the latest wave of the EBRD-EIB-WBG Enterprise Survey (Enterprise Survey 2019), which collected data on more than 28 000 registered firms from 2018 to 2020. The survey was completed just before the onset of the pandemic, providing a structural snapshot of firms in the region. The report also uses the first round of the COVID-19 Follow-up Enterprise Surveys of more than 16 000 firms, which the World Bank carried out to examine how firms adapted to the crisis.

During the first wave of the pandemic, firms on average lost 25% of revenue and shed 11% of their workers. Strong government intervention such as job retention programmes, grants, debt moratoriums, guarantees, tax breaks and interest rate subsidies softened the pandemic’s blow. Only 4% of firms filed for bankruptcy or closed permanently.

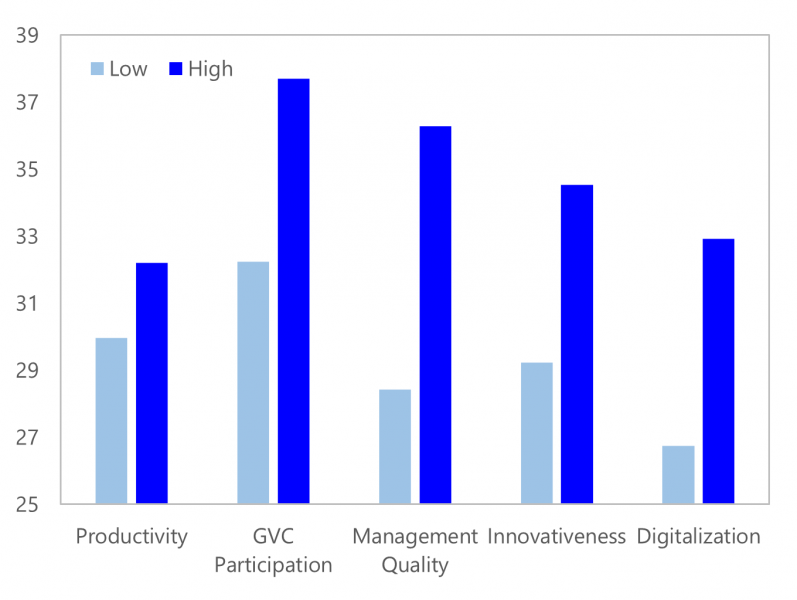

Figure 1: The effect of firm characteristics on adaptation success during the pandemic

Source: Authors’ calculations based on COV-ES.

Note: The chart plots the average predicted probability of firms’ adaptation during the pandemic, in per cent, based on separate logit regressions on relevant firm characteristics pre-COVID-19. Adaptation is measured as the simple average across firms’ responses to questions about starting or increasing business activity online, delivery of goods and services, increasing use of remote working, adjustment in production or services, and access to policy support.

Economic success in this region has been linked to firms’ integration in global value chains. This integration has led to more innovation, with evidence of causality through better management and transfer of technologies. Global value chain participation also influences firms’ capacity to adapt to shocks. In this context, the European Union has served as a growth catalyst, a trade facilitator and a driver of innovation.

Most firms in Eastern Europe and Central Asia are actively involved in trade. This increases productivity, innovation and growth. Trade varies across the different regions, however, with a higher number of firms exporting goods in Central and Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans than in lower- and upper-middle-income countries, while the Eastern Neighbourhood and Central Asia lag behind.

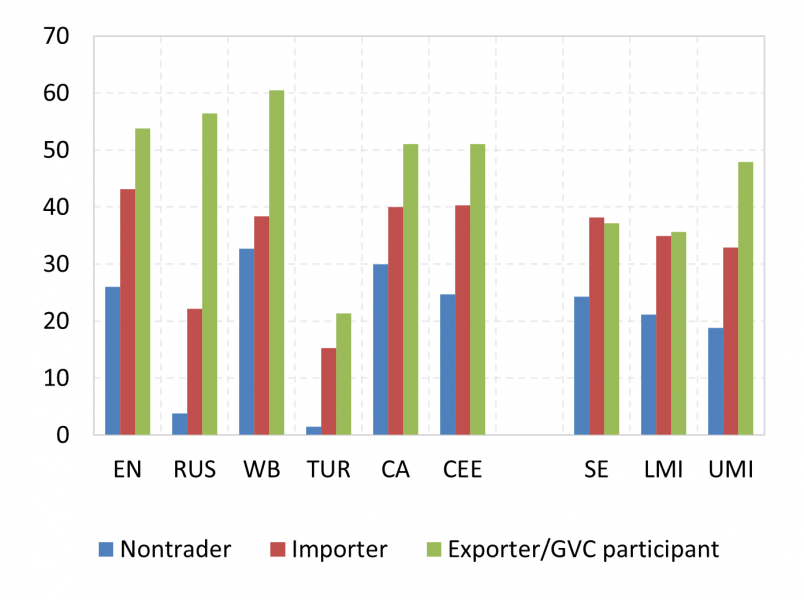

Figure 2: Innovative firms, by trading profile (% of firms)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the EBRD-EIB-WBG Enterprise Survey.

The sub-regions of Eastern Europe and Central Asia are still lagging behind in green management practices, specifically in setting targets for energy use and emissions. Despite a shift away from coal and oil towards nuclear power and renewables, the region is still highly reliant on fossil fuels. In 2018, these generated three-quarters of its electricity. Several countries continue to provide generous subsidies that lower the price of gas and other fossil fuels, slowing down the motivation to cut emissions.

Measurable and realistic environmental objectives would help firms improve their environmental performance.

Figure 3: The average quality of management differs across sub-regions of Eastern Europe and Central Asia

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the EBRD-EIB-WBG Enterprise Survey.

The financial systems in Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans have held up well so far. Firms continue to rely largely on bank credit for external finance. Capital markets are underdeveloped, and the availability of venture capital, private equity and leasing is very limited. Many firms continue to perceive a lack of access to finance as an obstacle and remain either financially autarkic or credit-constrained.

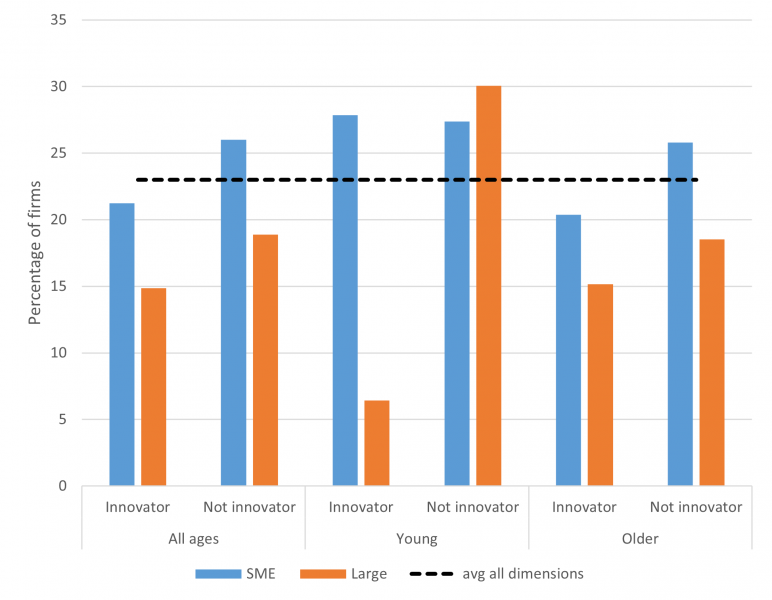

Figure 4: Credit constraints: breakdown by innovators, firms’ age and size

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the EBRD-EIB-WBG Enterprise Survey.

The structural drivers and constraints on private sector transformation in Eastern Europe and Central Asia provide valuable insights to inform policy development as the region adapts to the new shock and geopolitical context emerging from the war in Ukraine.

The COVID-19 outbreak put businesses in Eastern Europe and Central Asia through a severe test. Their resilience has been enhanced by effective policy support. Firm performance before the pandemic, as well as financial links to a parent company or to the financial sector, have also enhanced resilience. Supporting innovation, digitalisation and firms’ integration into global markets can help business resilience and adaptation to the new economic environment.

Heightened geopolitical risks and uncertainty have now increased the risk of a retrenchment of cross border flows and trade. It is therefore becoming imperative to reflect on the cost that de-globalisation might have on the region, even beyond the direct disruption of trade. Access to information and know-how through participation in global value chains, foreign licensed technology and modern management practices are among the most important ingredients for boosting innovation and competitiveness. Investment in digital infrastructure and in workers’ skills should be prioritised. The pandemic has had a highly uneven impact across sectors. The new shock is affecting businesses through sharp rises in production costs and disruptions to critical inputs. Policies can help by ensuring that sufficient liquidity remains available to affected firms. They can also support severely impacted viable firms with temporary schemes and adequate safeguards. Support for intensive training programmes to improve the management of SMEs and enhance incentives to reskill the workforce can be considered, particularly in less well-connected areas where there is a need to attract innovative firms. This could help to rebalance discrepancies in economic development and social cohesion within the region and to improve resilience and adaptability to present and future shocks.

For the transition to sustainable growth and a green economy to be a success, the private sector needs to apply its ingenuity, investment and entrepreneurship to the endeavour. The transition to a low-carbon future requires private enterprises to improve their green management by, for example, investing to enhance their energy efficiency and/or reduce their negative environmental impact, thus underscoring the importance of supporting green investment. Supporting energy efficiency could also contribute to reaching the twin goals of greening the system and energy security in the current geopolitical context. On the other hand, policymakers need to provide a business environment that is conducive to green investment and nudges all businesses to improve their management practices and, more broadly, their corporate responsibility on environmental, social and governance matters. This is a crucial point in time as the energy shock and energy security might lead to a reversal of the trend towards decarbonisation. Providing a clear path and aligning incentives towards the green transition remains key.

Continued development of the financial sector will be essential, not only to support firms during crises, but also to relieve credit constraints that limit firms’ growth during normal times. Improvements in collateral frameworks can help to tackle inefficiencies in the allocation of credit, reduce risks and increase the accessibility of credit. Targeted financial and advisory support can reduce constraints and increase firms’ investment opportunities, particularly for SMEs, young and innovative firms. This would increase firms’ resilience to shocks and contribute to mitigating currently heightened risks. Further diversification in terms of financial instruments and products is warranted. For example, the deployment of guarantee schemes can boost banks’ risk-taking appetite, while their effectiveness can be enhanced via better risk assessment and screening capabilities. Moreover, financial literacy as well as improvements in audit and accounting standards, in conjunction with a genuine reform agenda, would reduce information asymmetry, thus increasing firms’ capacity, appetite and confidence in engaging with the banking sector.

Non-traders: firms with neither exporter nor importer activity. Global value chain participants: firms engaged in both importer and exporter activity.