This policy brief is based on Wessels and Broeders (2022).

In this final section, we develop a set of guidelines that can serve as a basis a central bank’s capital policy. How these guidelines work out in practice depends on the specific mandate and situation of a central bank.

A central bank’s capital policy has a target capital level that may correspond to a lower confidence level than the Basel capital requirements for commercial banks.

A central bank cannot default on its own currency. Therefore, a central bank’s capital is auxiliary in ensuring stand-alone effectiveness, independently of the government. In contrast to the Basel requirements for commercial banks, the central bank’s capital target may cover the same financial risks with a lower level of confidence, e.g. 99% on a one-year horizon.

A central bank’s capital policy is based on an assessment of financial risks, covering both calculable financial risks and latent risks.

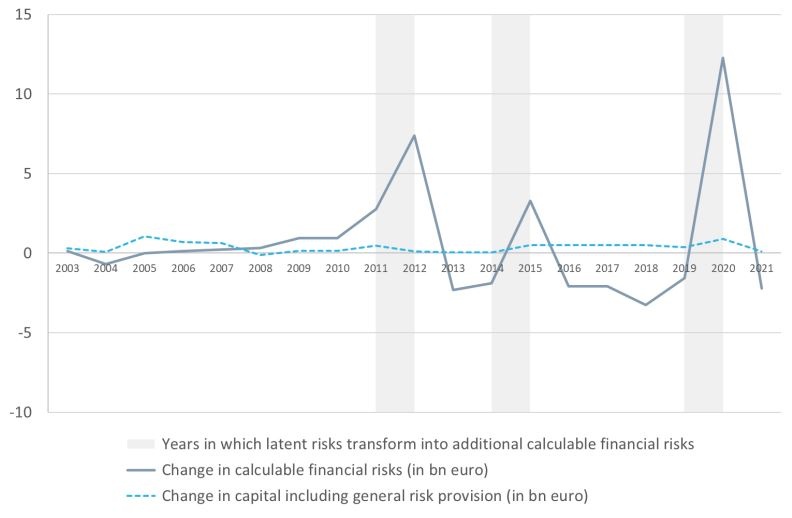

A central bank needs adequate capital in order to absorb the financial risks in a stand-alone capacity. An important difference as compared to commercial banks is that central banks are exposed to latent risks in addition to calculable financial risks. The central bank capital policy should take these latent risks into account. Historical analyses and scenario analyses can give an indication of the order of magnitude of these latent risks.

A central bank’s capital policy has a target capital level that is stable relative to the key macroeconomic variables and sustainable for a long term.

A central bank’s calculable financial risks can be erratic over time due to the transformation of latent risks into calculable risks following monetary policy interventions. Latent risks are likely to be proportional to macro developments such as GDP or the size of the banking sector in the long run.

A central bank’s capital policy focusses on buffers that are directly and unconditionally available to absorb losses.

In addition to shareholder equity, a general risk provision can be part of capital provided it has full loss-absorbing capacity for a broad range of assets and risk types. Revaluation reserves for specific types of assets and guarantees from the government are not equivalent substitutes for shareholder equity and a general risk provision.

A central bank’s capital policy relies on the central bank’s own profitability for capital growth.

The central bank uses its annual profit as the source of capital growth. If the annual profit is insufficient to achieve the capital target, the central bank should be allowed make this up from profits in later years. Capital which is temporarily below its target level is not problematic as long as recovery is feasible in the medium term (five to ten years). Full retention of annual profit should be undisputed if necessary. In extreme circumstances, if the central bank has negative equity for a long time, a recapitalization may be necessary. Excess profits, when the capital target is reached, should be paid out to the shareholder.

A central bank’s capital policy is robust and objective.

As both annual profits and calculable financial risks show erratic behaviour, a central bank’s capital policy should be robust and be able to accommodate a wide range of states of the economy, from good to bad. Defining a capital target and linking it to GDP creates objectivity.

A central bank’s capital policy is simple and transparent.

The capital policy should be made public in a way that can be easily understood by stakeholders and the public. Every year the central bank should explain how capital is growing in relation to the target and the calculable financial risks. The effectiveness of the capital policy could be evaluated and published on a regular basis, for instance every five years.