This policy brief (based on Kruszewski and Szadkowski, 20212) proves, on the basis of theoretical considerations concerning the simplified model of the balance sheet and profit and loss account of the central bank, that the financial result of the central bank and the elements forming it as well as the distribution of profit to the state budget serve to transfer benefits between different sectors of the economy. In this respect, the central bank acts as an intermediary in the flow of these benefits. The directions of the transfers indicated depend on the structure of central bank assets and liabilities.

The central bank (hereinafter CB) is perceived mainly through its functions in the economy. It is less frequently seen as an economic entity whose tasks performed determine both the structure of its balance sheet and financial result.

The CB is the sole issuer of CB money, which can be understood here as the sum of the monetary base, the balance of government accounts and the balances of liquidity-absorbing operations. The CB money so understood is presented in its balance sheet under liabilities.

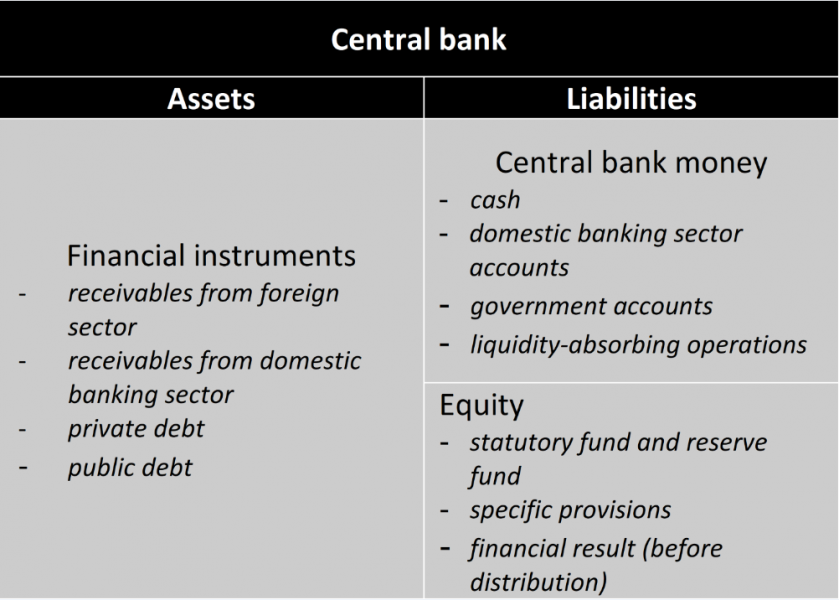

The asset side of the CB includes mainly financial instruments, which are financed by the CB mentioned money issued and its equity. The type and currency of financial instruments held in its portfolio are diversified and depend on the circumstances under which the CB operates. They can comprise either foreign currency or assets denominated in domestic currency, representing receivables from the domestic banking sector, the government and the non-banking private sector3 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Simplified balance sheet of the central bank

Source: own study.

The CB’s assets and liabilities are associated with specific revenue and costs. However, it should be noted that the income and expenses of the CB simultaneously constitute expenses and income of the other sectors of the economy, respectively. From the perspective of the CB, three major categories of income or expenses related to its assets and liabilities can be distinguished. They are interest, differences resulting from a change in the price of assets (price differences), and from changes in foreign exchange rates (foreign exchange differences). For each of the categories of income and expenses a distinction can be made between those paid (realised) and those not paid (unrealised).

Interest income applies to almost every asset of the CB. A similar situation exists with respect to price differences, which are most common with respect to debt securities held by the CB. On the other hand, foreign exchange differences relate to financial instruments denominated in foreign currency.

On the contrary, in the case of CB liabilities which due to their nature generate costs, it should be noted that some important items of liabilities do not result in expenses for the CB. This applies to liabilities due to money in circulation or the bank’s equity.

Moreover, certain expenses relate to resources that do not appear on CB’s balance, e.g. the remuneration of the bank’s employees or expenses incurred in connection with services provided to the bank by external entities (e.g. IT services). While for the CB these costs reduce its financial result, for other sectors (e.g. the non-banking private sector) they represent their revenues.

The CB’s income and expenses constitute its financial result. The method of calculation of the CB’s financial result depends on the accounting policy applied. This policy or, to be more precise, the accounting rules determine such issues as:

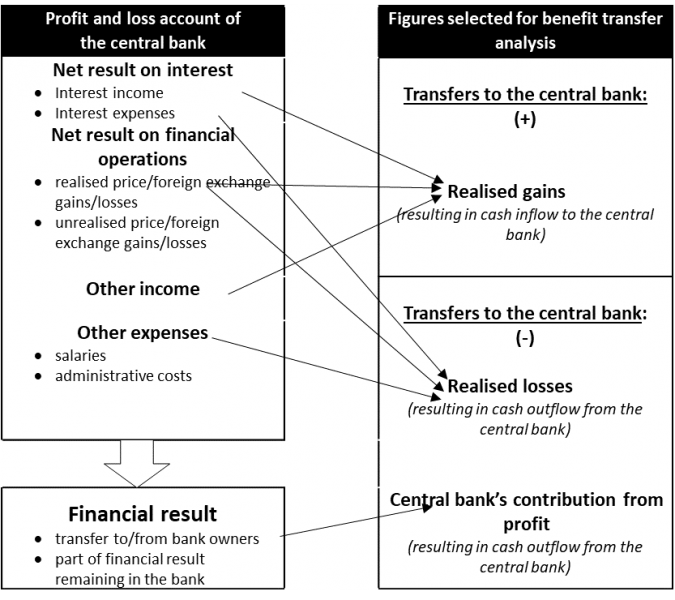

The analysis of income and expenses allows us to outline a simplified profit and loss account of the CB (Figure 2, left-hand panel). However, the CB’s financial result is subject to further distribution. The whole financial result generated by the bank, or a part thereof, can be distributed to recipients (in case of profit) or covered by, for example, the owners of the bank (in case of loss) or may remain in the CB (e.g. as undistributed profit or uncovered loss).

Figure 2. Simplified profit and loss account of the central bank

Source: own study.

With CB’s financial result are associated benefits transfers, which when flow into the bank – increasing its financial result – represent income, while when they flow out of the bank – reducing its financial result – represent expenses. It should be emphasised that benefits are understood very broadly, as gains for specific sectors of the economy. The analysis focuses on benefits considered from the CB’s perspective. Thus, the income of the CB is benefits with the CB acting as their beneficiary. On the other hand, the CB’s costs are benefits for other sectors of the economy. The financial result of the CB, where the profit occurs, is the net benefit of the CB. On the contrary, when the loss occurs, it is the net benefit for other sectors of the economy. Profit transfers from the CB to an eligible recipient (e.g. the government) constitute the benefit of the latter.

Figure 2 (right-hand panel) presents the results of the analysis of the CB’s financial result impact on the direction of the benefits transfer4. Indeed, it should be noted that not all elements included in the CB’s financial result have an impact on the volume of benefit transfers. Thus, if CB income is realised, it implies the transfer of benefits to the CB from other sectors of the economy. On the other hand, if the CB incurs expenditure generating expenses, they trigger an outflow of benefits from the CB and their transfer to other sectors of the economy. On the contrary, if the CB distributes the profit, then the effects of the operation are similar to the operation associated with incurring expenses by the CB.

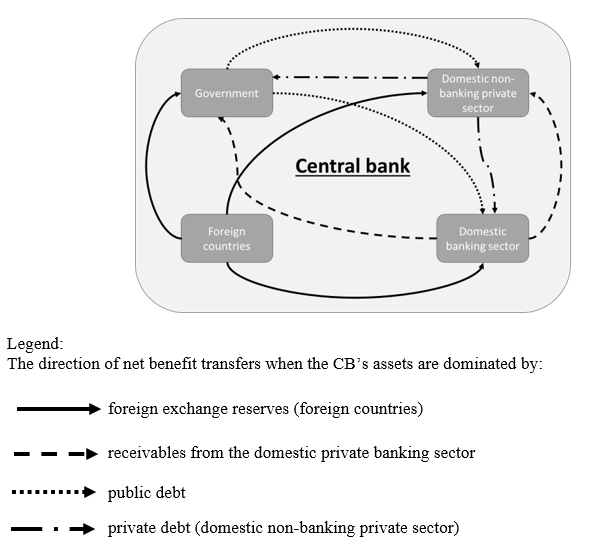

The analysis of the aggregate impact of the structure of CB’s assets on the direction of transfers of benefits in the economy associated with the CB’s financial result (Figure 3) should be preceded by the assumption, that the bank generates the profit which is fully transferred to the state budget and operates in the environment of positive interest rates. In addition, in order to present the directions of transfers more clearly, it should be also assumed, that the CB’s assets are dominated by the particular type of assets. Later some of the assumptions adopted will be loosened.

Figure 3. Final transfer of benefits in the case of central bank’s profits depending on the structure of its assets

Source: own study.

When the CB’s assets are dominated by foreign assets, the transfer of benefits from foreign countries (income on foreign assets) to the domestic banking sector (due to expenses such as interest on bank accounts), the domestic non-banking private sector (refers to the operating costs of CB – e.g. salaries) and the government (profit distribution) will take place.

When the CB’s assets are dominated by domestic assets, the direction of the transfers of benefits will depend on the type of assets held by the CB. If these are assets of the domestic banking sector, the transfer of benefits from this sector occurs (surplus of income over expenses from operations with the banking sector) to the private sector (due to the operating costs of the CB) and the government (profit distribution).

However, if the CB holds securities purchased from the private sector, the transfer of benefits will take place from that sector (the surplus of income on private sector securities over the operating costs of the CB) to the banking sector (this refers to the expenses of the interest on bank accounts) and, as in all previous cases, to the government (profit distribution).

The case of transfers of benefits is worth particular attention when the CB’s assets include public debt. Under such circumstances, the transfer of benefits from the government sector to the domestic banking sector and the non-banking private sector occurs. Indeed, the interest income received by the CB on government bonds will finance its interest expenses on banking sector accounts and its operating costs, i.e. transfers to the private sector. CB’s net profit will be paid to the state budget. However, if CB expenses in the form of interest on domestic bank accounts did not occur and the operating costs of CB were negligible, the transfer of benefits in the form of interest on public debt from the government to the CB would be offset in the form of payment from the CB’s profit to the state budget. This, in turn, could be considered as issuance of interest-free debt by the government.

It should be stressed that in the cases discussed so far, CB only acts as an intermediary in the transfer of benefits between individual sectors of the economy (it is therefore placed at the centre of Figure 3 and is neither a beneficiary nor a provider of net benefits to any sector of the economy).

However, if one of the assumptions made is loosened and the CB is permitted to incur a loss, the situation is more complicated. The CB’s loss means a surplus of its expenses over its income, i.e. transfers of benefits from the CB exceed transfers of benefits to the bank. This means that the CB transfers its net benefits to other sectors of the economy. If recapitalisation is made by the government, the transfer of benefits from this sector to the CB will occur.

The case where the CB becomes an entity transferring its net benefits to other sectors of the economy is not limited to uncovered loss. Such a situation is also possible when the bank uses its capital to finance deficit-generating activities in other areas of its operation. It takes the form of creating new one or using previously established provisions and reserves to cover identified risk, the occurrence of which may result in expenses (e.g. financial risk). This, in turn, means that if the assumptions regarding the payment of all profits to the state budget is loosened in favour of the CB retaining a part of the revenue generated, then the CB can not only transfer its net benefits to other sectors of the economy but it can be also the beneficiary of the net benefits transferred from other sectors. However, it should be indicated that creating provisions or reserve funds in one period and using them in another period practically means the redistribution of benefits between sectors of the economy with the difference that it occurs in different periods.

Finally, it is worth considering the case where another assumption is loosened, i.e. the diversification of CB assets will be permitted, which means that the bank will hold assets both in domestic currency and in foreign currency, without indicating what assets prevail. In such a case, while maintaining the assumption of generating profit and allocating it entirely to payments to, for example, the government, the CB will continue to act as an intermediary in the transfers of benefits. However, it is much more difficult to identify the clear direction of benefit transfers between sectors of the national economy. They can be determined then by the difference between the income on assets and the expenses on the CB’s liabilities towards the relevant sector of the economy.

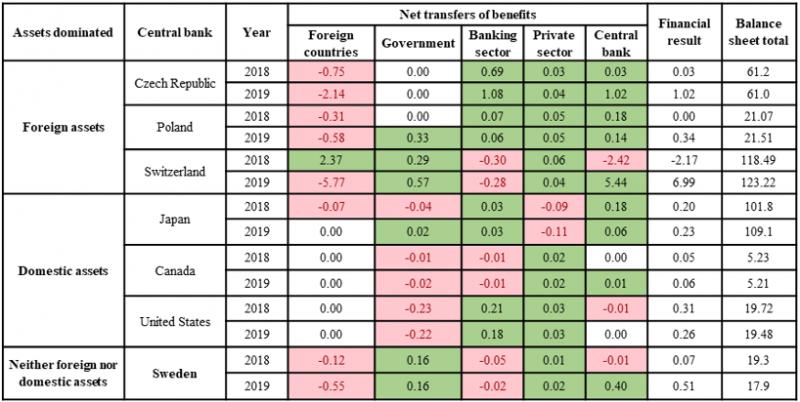

Directions of benefit transfers depending on the structure of the selected CB’s assets were estimated based on the profit and loss account and information concerning the distribution of the financial result provided in the CBs’ reports for two consecutive years (2018-2019; see Table 1). In order to simplify the analysis carried out (bearing in mind the observations made when discussing Figure 2), it was assumed that all income and expenses recognised in the CB’s financial result are realised.

Table 1. Transfers of benefits in selected central banks (in relation to GDP, in %)

Notes:

1) In columns representing transfers of benefits, positive figures represent net transfers to this sector (green shading) while negative figures represent net transfers from this sector to other sectors (red shading).

2) For Switzerland, the result on gold is treated as part of CB transfers.

Source: own study based on the financial statements of central banks, AMECO database (accessed on 6 May 2020) and IMF (International Financial Statistics, accessed on 6 May 2020).

As we can see, if the CB’s assets are dominated by foreign assets, then transfers from foreign countries to sectors of the domestic economy occur5. The beneficiaries of these transfers in addition to the domestic banking sector, the private sector and the government, are CBs themselves (this results from the mentioned possibility for CBs to create provisions and reserve funds).

In the case of CBs where dominate domestic assets the foreign sector plays virtually no significant role in the transfers of benefits6. Moreover, in those banks where Treasury securities dominate in the assets (Fed and Bank of Canada), despite distribution of the CB’s profits to the state budget, the net transfer of benefits from the government sector to other sectors of the domestic economy ultimately occurs: in the case of Canada – to the private sector, and in the case of the United States – to the banking sector.

Kruszewski K., Szadkowski M. (2021). Impact of the central bank’s financial result on the transfers of benefits across sectors of the economy, “NBP Working Papers”, Narodowy Bank Polski, No. 340

[https://www.nbp.pl/publikacje/materialy_i_studia/340_en.pdf].

Polański Z., Szadkowski M. (2020). Seigniorage and central banks’ financial results in times of unconventional monetary policy, “NBP Working Papers”, Narodowy Bank Polski, No. 331

[https://www.nbp.pl/publikacje/materialy_i_studia/331_en.pdf].

The views expressed in this policy brief are the opinions of the authors and should not be interpreted as the position of Narodowy Bank Polski.

Where also all references are included.

In our simplified accounting model except CB we distinguish the following sectors of the economy: the domestic private banking sector, the domestic non-banking private sector, the government and the foreign sector.

In Kruszewski and Szadkowski (2021) we discuss also the impact of those transfers on the volume of CB’s money creation depending on the structure of assets (foreign vs domestic assets).

Except for Switzerland in 2018, when transfers in the opposite direction took place – this resulted from the appreciation of the Swiss franc, resulting in losses from the revaluation of foreign assets.

Apart from the CB of Japan in 2018.