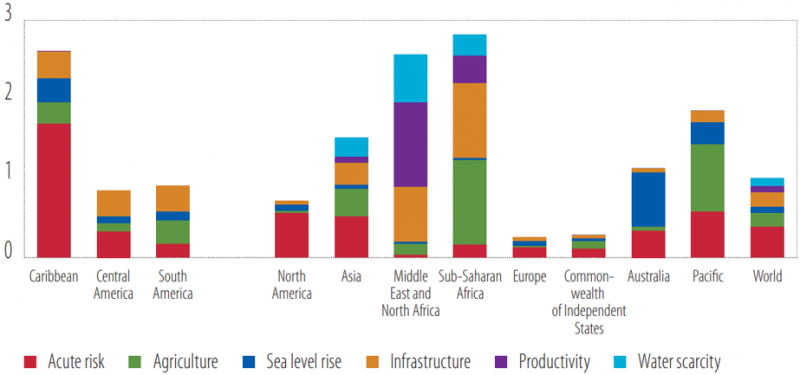

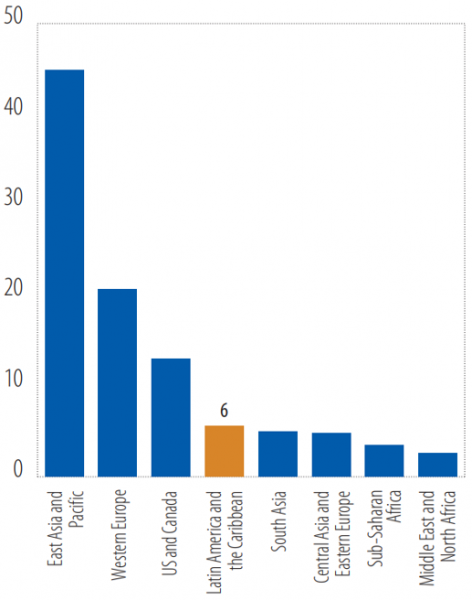

Figure 1: Economic impact of physical risk in the world, by component (world average = 1)

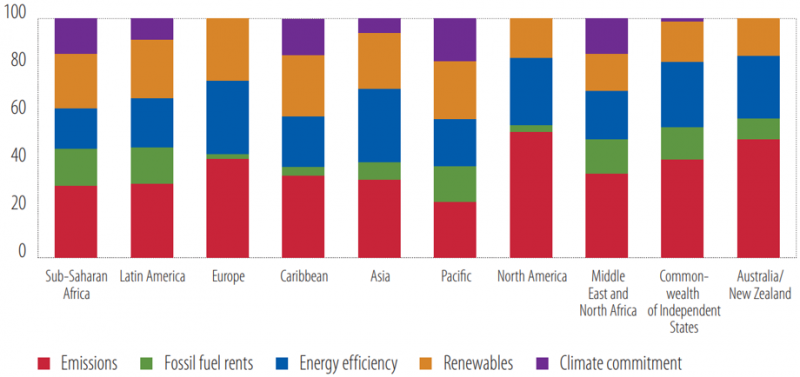

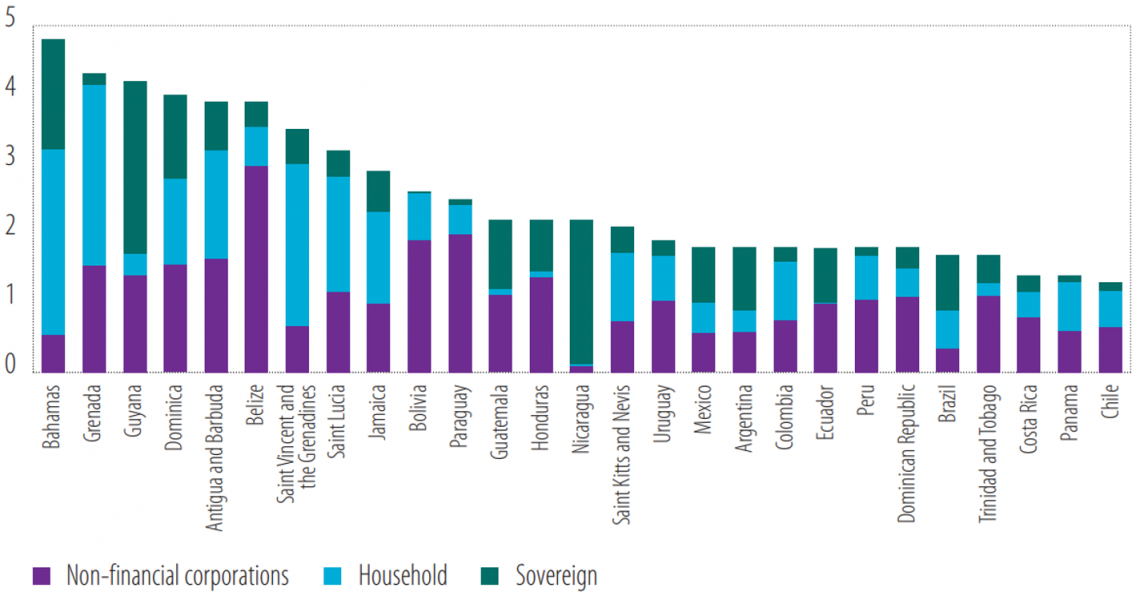

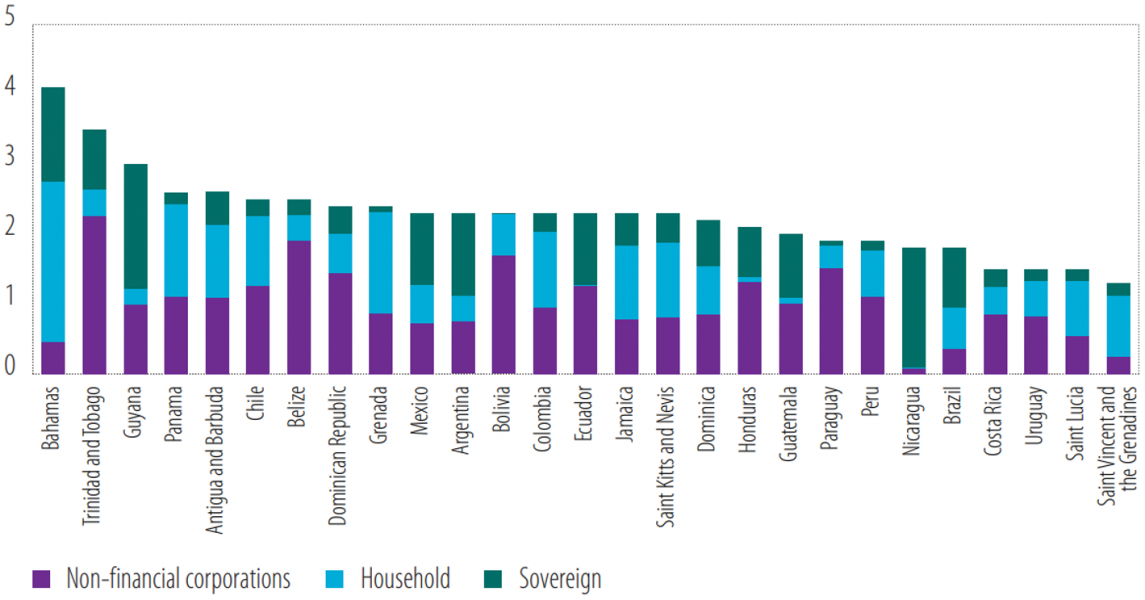

Figure 2: Contribution of the main components to the overall transition risk score (% of total)

Defined as the sum of the damage deriving from natural disasters, production losses in agriculture, the impact of sea level rise, the impact on infrastructure, the impact of heat on labour productivity and the effects of water scarcity.

Defined as the changes to our systems needed to transition towards a lower-carbon economy and measured by scores for countries’: level of emissions; exposure of the economy to fossil fuels; energy efficiency; deployment of renewable energy; country preparedness.