This Policy Brief is based on the publication “Corporate bond markets in Europe – a structural perspective” by Heike Mai, Deutsche Bank Research, October 2024.

Abstract

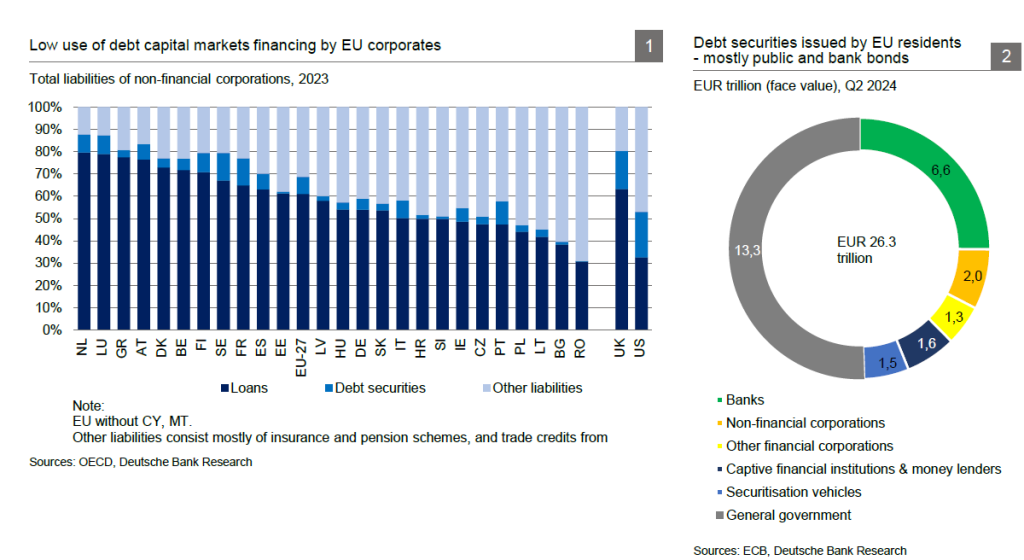

The European economy is facing huge investment needs in order to foster innovation and to strengthen competitiveness. Markets could provide more funding, as a comparison with the US shows. Debt securities issued by non-financial corporations in the EU amount to EUR 2 trillion, of which EUR 1.7 tr is in the euro area, but there are pronounced differences between countries. One-third of the outstanding corporate debt is held domestically, while almost half is held by investors from the euro area excluding the home market. Investment funds, insurance companies and pension funds are the most important investor groups. Boosting the European bond market through deeper integration continues to rank high on the political agenda. Current initiatives also aim at enlarging the investor base by facilitating markets-based products for private households.

The European economy is facing huge investment needs in order to foster innovation and to strengthen competitiveness, thus lifting economic growth. Banks are the dominant provider of credit to companies in Europe, yet loans will hardly satisfy the needs, not least due to overall limited capacity of banks’ balance sheets. Securitisation can help but it remains significantly subdued. Similarly, other markets could provide more funding, however, they are also only a fraction of the size in the US – be it venture capital, equity or bonds. Concluding our mini-series on European capital markets, in this note we will shed light on the role of debt securities.

Thus, taking stock – where do European bond markets stand today, from a structural perspective? We will look at both the issuer and investor sides, at interest rate and maturity features. Because fragmentation continues to be high and national market structures differ substantially, our analysis will cover the aggregate EU as well as the individual country level, with a particular focus on Germany and also including the UK and US as a reference (where possible).

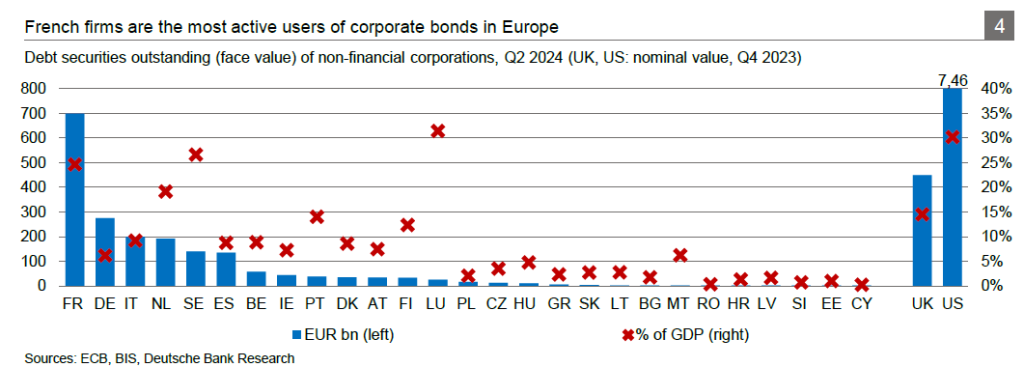

Debt securities issued by non-financial corporations in the EU amount to EUR 2 trillion (Q2 2024)1 but this is just 8% of the total EUR 26.3 trillion outstanding. The public sector (50%) and the banking sector (25%) account for the lion’s share, other financial firms for 5%. Another 12% stem from financial vehicles2. Across all issuers, France (EUR 5.6 tr), the UK (EUR 5.3 tr), and Germany (EUR 4.3 tr) have the largest markets in Europe. Considering the size of the German economy, its bond market is surprisingly small, though – it makes up 16% of the EU total, compared to a GDP proportion of 24%.

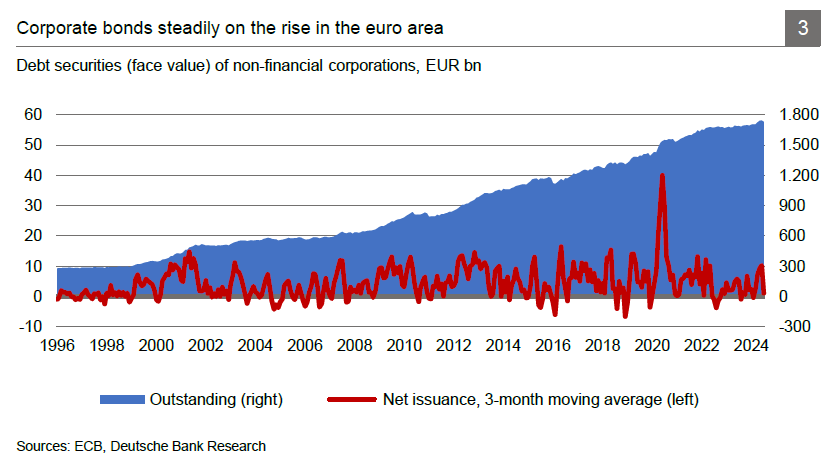

Non-financial firms3 are in focus when it comes to the transformation of the European economy and how to make it more competitive. This is true for both non-financial corporations (NFCs) as well as unincorporated businesses and self-employed – but data on the funding structures of the latter is relatively scarce. “Corporate bonds” in the narrow sense are issued by NFCs and typically refer only to paper with maturities longer than one year. Commercial paper have shorter maturities. All in all, of the EUR 2 tr in corporate debt securities in the EU, EUR 1.7 tr is in the euro area. Here, market growth accelerated with the onset of the financial crisis. It has averaged 6.8% p.a. since then and also significantly outpaced inflation4. Net issuance increased from an annual average of EUR 39 bn in 1998-2007 to EUR 66 bn in 2014-23.

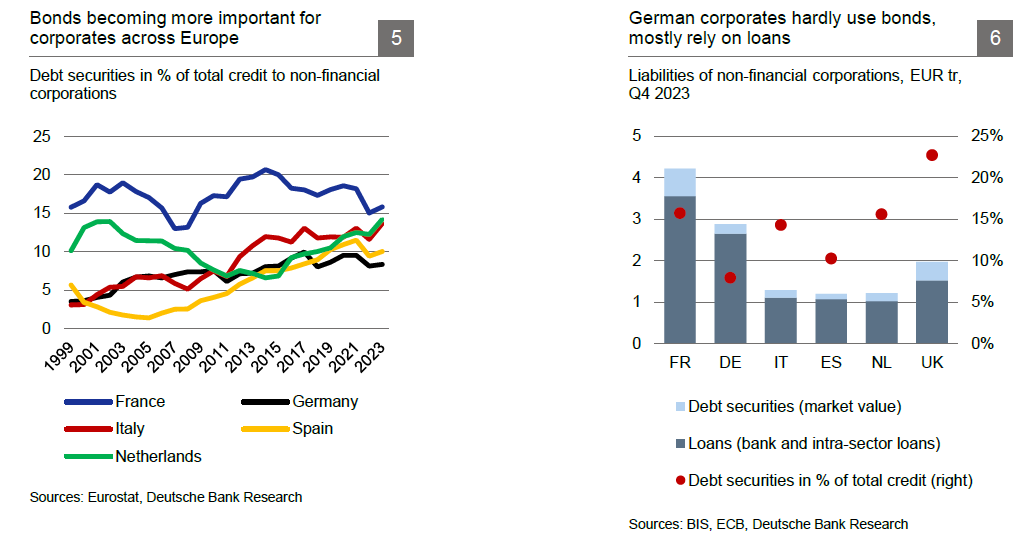

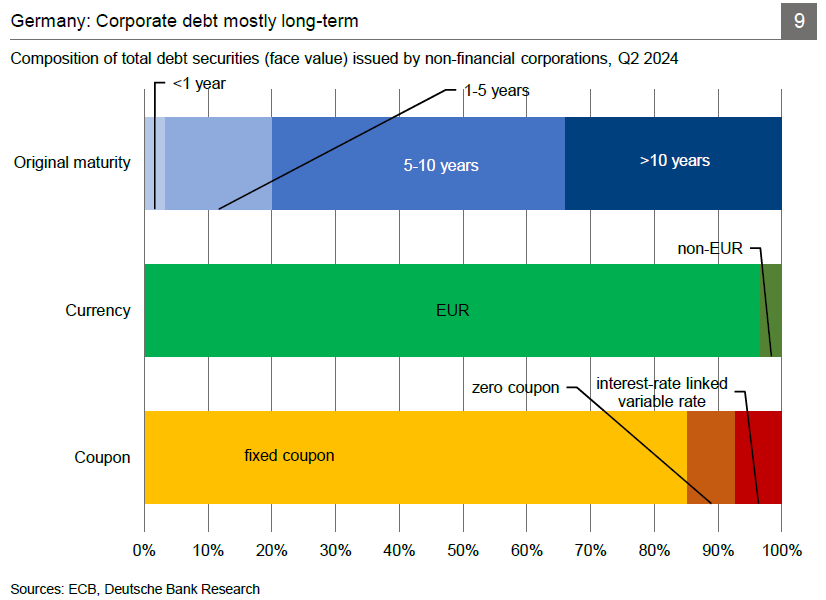

Within Europe, there are pronounced differences between countries. French companies are the most active issuers, their outstanding volume of debt securities is by far the highest (EUR 689 bn – which is more than the figure in the next three largest EU states combined). Together with Sweden and the offshore hub Luxembourg, France is also the only country where corporate debt as a share of national GDP (25%) is comparable to the US (around 30%, and EUR 7,465 bn in absolute terms). Corporate bonds play an important role in the Netherlands (19% of GDP) and the UK (14%), too. In Italy, Spain and many other Western European economies, they amount to about 9-14% of GDP. Germany, however, is a clear laggard (6%, EUR 275 bn) and its market a minnow compared to the country’s economic size. In Central and Eastern Europe, where GDP levels tend to be lower and national currencies are more prevalent, corporates so far make very little use of debt capital markets.

There is no single reason for the varying use of bonds, and the differing funding structures in general, across Europe. Long-standing traditions and preference for established instruments may play a large role, coupled with diverging national tax regimes and regulations. Yet a clear pattern does not seem to exist.

As regards the choice between bonds or bank loans, debt securities play only a minor role today, despite an upward trend in most countries. In Italy and Spain, the share of bonds in total credit outstanding at NFCs has increased to 14% and 10%, respectively, over the past 20 years. Partly, this may have been driven by the bank credit crunch following the European debt crisis, which forced greater orientation towards the capital market. In Germany, the bond share went up from 5% to 8%. French and Dutch firms are leaders in this respect, with debt securities accounting for 16% of total credit raised. But even this means a profound dominance of loans (from banks or trade payables).

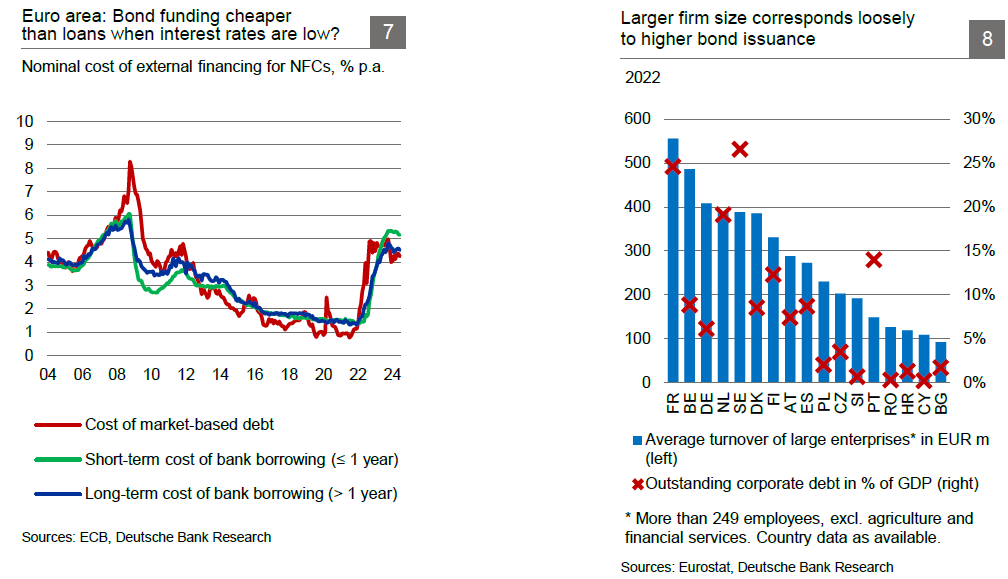

The cost of different instruments is an important criterion when deciding about the funding mix. Overall, the cost of credit will depend to a large extent on a firm’s credit worthiness. And generally, it has been extraordinarily (and increasingly) low over the past decade, at least before the inflation shock of 2022 which triggered a surge in central bank and market interest rates. In the euro area, interest rates on both corporate debt and corporate loans fell from about 4-6% before the financial crisis to just 1-2% in 2016-21, providing for a substantial benefit to all businesses. Remarkably though, throughout almost the entire decade starting in 2013, interest due on bonds was less than interest due on bank loans. Most of the time, the difference was not huge yet sizeable, amounting to a few tenths of a percentage point. Of course, this can have a significant cumulative impact in the long run. Hence, it may have been one of the decisive drivers of the general upward trend in the use of corporate bonds across the monetary union in recent years. Now that interest rates are back at their pre-financial crisis level (but starting to decline again), it is an open question whether this rate differential will continue to exist, and what the implications for the bond-loan mix might be.

Total corporate indebtedness may have a mixed impact on the use of bonds as a source of funding. On the one hand, less indebted firms may be in a better position to place bonds in the market, because they are seen as less risky. On the other hand, companies with high but stable debt levels, a long history of bond issuance and a strong track record in repayments & rollovers may be regarded as credible borrowers and experienced in managing their stock of debt, which increases investor confidence.

Firm size may also influence the likelihood of going to the debt capital market. Larger firms, i.e. those with a high turnover, may be more interested in larger financing rounds and in a diversified funding base as well as find it easier to generate sufficient investor demand for their paper. Admittedly, the empirical evidence is not overwhelming. Firms with at least 250 employees in France, the Netherlands or Sweden are indeed particularly large and also have lots of bonds outstanding, while such companies on average have a relatively low turnover in many Central and Eastern European countries – where bond markets tend to be very small, too. However, Germany and Belgium, e.g., have quite large firms which still make only limited use of debt capital.

On a side note: firm size may also partly explain the slightly lower market interest rates than aggregate bank lending rates shown above: indeed, rates on larger loans (EUR > 1 m) tend to be somewhat lower than those for smaller credit. The former is typically used by larger firms, which also have bond issuance as an alternative option and, on average, may be seen as more robust and resilient to shocks than SMEs which usually rely on bank funding. The rate differential between large bank loans and corporate bonds is likely to be smaller than for all loans combined.

In Germany, there is not just one reason for the low volume of corporate bonds in – low both in relation to GDP and to firms’ total external liabilities. Easy access to bank loans is probably one. Besides, loans could be less expensive, especially if documentation and reporting obligations are taken into account. This may not be much extra work for publicly traded corporations, but in Germany, many mid-cap and large-cap companies (“Mittelstand”) are family-owned and would face additional costs. There are 1,125 large companies (annual turnover of EUR 500 m or more) in the country, of which only 10% are currently rated by an agency, and the share is likely to be even lower for smaller companies.5 The fixed cost, especially of the first issuance, may constitute a considerable hurdle. On top of this, private owners are often reluctant to provide the necessary degree of transparency.6 Last but not least, bond issuance usually requires a minimum volume in the range of several hundred million euros – more than what most Mittelstand firms need in a single funding transaction.7

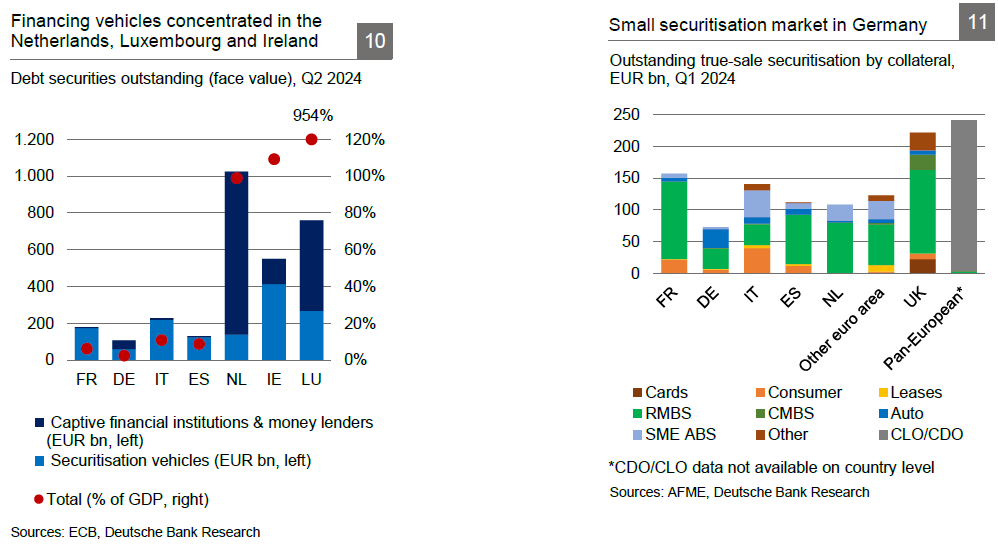

Of the EUR 275 bn of debt securities outstanding by German NFCs, almost all is denominated in EUR (97%), as funding needs in other currencies are probably covered via affiliates in other countries. Most debt has a fixed coupon (85%); variable interest rates account for only 7%. Firms typically issue longer-term bonds – nearly half of all debt securities have an original maturity of between 5 and 10 years, and another third of over 10 years. Short-term financing needs are usually covered via bank loans rather than through the capital market, as was again the case in recent moments of turmoil during the onset of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 and the energy crisis in 2022. Hence, short-term debt securities like commercial paper constitute a relatively small segment of the market (3%) – and indeed have even shrunk over the past couple of years, in absolute numbers.

By contrast, corporates in France use the market also for short-term credit, 7% of their debt is issued with maturities below 1 year. Such paper might meet local investor demand, as money market funds (MMFs) have long played an important role in the French financial market. They are less common in other European countries, except for the financial hubs Ireland and Luxembourg. In addition, French companies raise more funds denominated in foreign currencies within the local market (15% of total debt outstanding), which places them second only to the Netherlands (27%) among the larger economies.

However, the official statistics – which are based on legal-entity reporting – may underestimate bond issuance in large countries to some extent, especially for non-financial companies (and banks). These sometimes have financial subsidiaries in countries with a more favourable regulatory or tax framework, where actual issuance takes place before such funds are channelled back towards the parent in the home country. For instance, corporate bonds outstanding in Germany, France or Spain may not reflect the full debt outstanding of German, French or Spanish corporations. The opposite may be true for Luxembourg, Ireland and the Netherlands, where domestic firms may only account for part of the total stock of bonds issued in these countries. Admittedly, it is impossible to precisely adjust for these bonds issued by financial vehicles abroad which are controlled by the headquarter in a different country.8

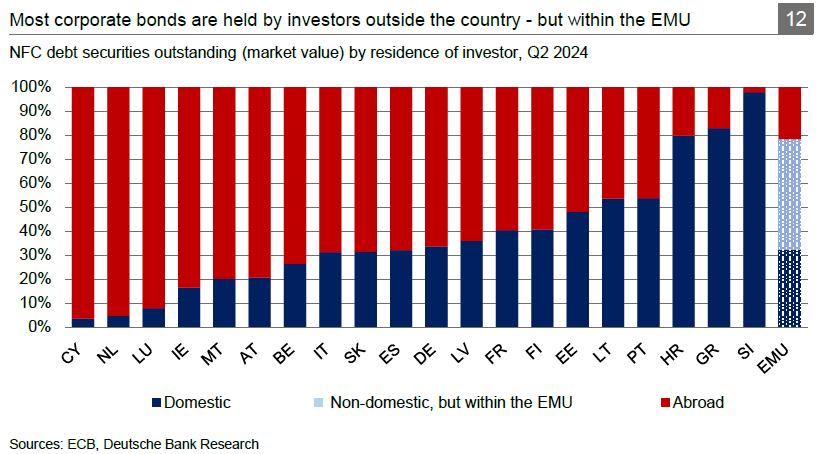

In total, such financing vehicles have issued debt of EUR 3.1 tr in the EU, with the (relatively heterogeneous and opaque) market consisting of two segments – i) securitisation SPVs which fund their asset purchases through bond issuance, and ii) “captive financial institutions and money lenders” (CFIs), which also include trusts, shell and holding companies, special purpose entities or conduits owned by foreign parent firms. Almost all financing vehicles are located in only a few euro-area countries: Luxembourg, Ireland and the Netherlands. These “offshore” financial centres account for three quarters of the EU market. Outstanding volumes in these countries equal or even amount to a multiple of the national GDP, while such bonds are of minor importance in France, Germany, Italy or Spain (3-11% of GDP).

A significant share of the capital raised by financing vehicles will ultimately serve corporate funding needs, of local operations as well as of non-resident parent entities. Securitisation vehicles hold EUR 429 bn of loans to euro-area corporates on their balance sheets, which – among other assets – are refinanced by EUR 1.5 tr in debt securities.9 Volumes are the highest in Ireland and Luxembourg, in nominal and also percentage terms, and make up almost half of the EU total. Often, the SPVs are not domiciled in the country of collateral.10 Similarly, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Ireland combined constitute over 90% of the CFI sub-market volume of EUR 1.6 tr.

Turning to the other side of the equation, it is similarly relevant who buys corporate debt securities issued in Europe.11 In the large national markets, roughly 30-40% is held by investors in the same country. In the offshore financial centres (Ireland, Luxembourg and – to a lesser degree – the Netherlands), resident investors own less than 20% of the local issuance. Countries with a small corporate bond market (in absolute terms) tend to attract somewhat fewer foreign investors and depend more on domestic investors. The large majority of the funds invested in euro-area corporate debt comes from within the monetary union, only about one-fifth from the outside – mostly the US.

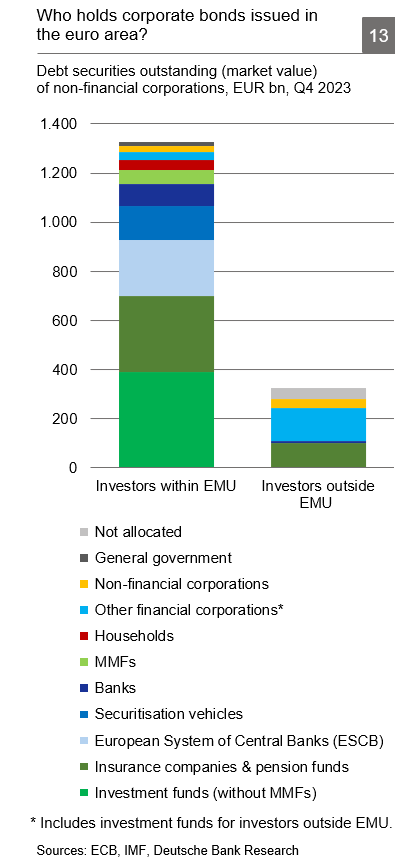

Investment funds are the most important investors in euro-area corporate bonds. They hold over one-quarter of the outstanding amount and most of them reside in the EMU. Insurance companies and pension funds account for another quarter of demand. The former are more important than the latter, though, which probably reflects the weak state of market-based pension systems in Europe. Thus, over half of all corporate bonds are in the hands of financial intermediaries on behalf of institutional or retail clients. Remarkably, securitisation vehicles not only act as issuers of bonds, but likewise hold 8% of the outstanding corporate debt, while banks have a share of only 6%. Other investor groups, incl. companies themselves, households (direct holdings) and MMFs, play only minor roles and are almost all based in the EMU.

Remarkably, the single largest bond investor is the Eurosystem. The ECB and the national central banks together hold EUR 217 bn12 or 13% of the EUR 1.7 tr of corporate bonds issued in the euro area. This is all the more striking given that the ECB has significantly tightened monetary policy over the past two and a half years, including ending its net asset purchases and reinvestments. Since mid-2022, the ECB has shrunk its corporate bond portfolio by EUR 13 bn, or roughly 6%. Since the beginning of 2025, maturing debt securities from the Pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) are no longer reinvested, as has been the case for other programmes. Now, the ECB will accelerate the de-investment process, resulting in a corporate portfolio reduction by 10% (ca. EUR 20 bn) envisaged until mid-2025.13

Debt securities as a source of corporate funding only play a minor role in Europe, despite an upward trend in the past decade, not least due to often slightly lower financing cost than for bank loans. On top of that, the use of bonds differs considerably between countries. Long-standing traditions, a preference for established instruments, tax rules and regulation or the availability of loans all may play a role. In addition, there tends to be more bond issuance in countries where firms on average are larger. At the same time, though, there is visible integration of European capital markets to some extent. On the issuer side, e.g., the securitisation also of corporate loans is concentrated in three hubs – Luxembourg, Ireland and the Netherlands. On the buyer side, almost half of the outstanding corporate debt is held by investors from the euro area excluding the home market, while only one-third is held domestically. Of course, large asset managers and insurance companies operate on a European or even global scale and they are the most important investors in corporate bonds.

A look at corporate funding in the US clearly shows that in Europe, there would be room for much more debt to be raised in the market. Yet the US is a fully integrated financial market. Strengthening integration also in Europe therefore promises deeper and more liquid markets, better conditions and more efficient capital allocation. Especially smaller issuers with a strong national focus could benefit from a larger non-domestic investor base in a market with fewer legal frictions. Also, capital pools could be scaled up by more market-based savings and pension products.

This vision has long been pursued by the EU and continues to rank high on the political agenda. The recent “Draghi Report”, requested by the European Commission, reiterated the critical importance to “build a genuine Capital Markets Union (CMU) supported by a stronger pension” in order to unlock the private capital needed to finance Europe’s strategic goals.15 This echoes the “Letta Report”, commissioned by the European Council, which also stressed the importance of a single financial market and called for a savings and investment union.16 The CMU, proposed as early as in 2014, particularly aims at harmonising and boosting corporate funding opportunities in EU financial markets.17 Currently, there is a discussion about greater harmonisation of national insolvency laws for non-banks which would especially foster bond market integration.[4] CMU-related initiatives also look to strengthen the investor side. Again, the aim is to attract more funds for the European economy via capital markets, e.g. through a Pan-European Pension Product for retail investors.18

Debt securities outstanding are measured at face value unless indicated otherwise.

For more details, see below.

This excludes non-bank financial corporations which comprise a wide array of enterprises like insurance firms, financial infrastructure providers or brokers. They have outstanding debt securities of EUR 1.3 tr.

The impact of EMU enlargement since 2008 has been negligible.

Mohr, Benjamin (2024), Die Rolle von Ratings in der neuen Ära der Bankenregulierung, Finanz-Briefing, Creditreform Rating, August 27.

See Schildbach, Jan (2024), European stock markets – hidden champion Germany, Deutsche Bank Research, Focus Germany, July 22.

German Council of Economic Experts (2023), Taking advantage of capital markets in Germany and the EU, in: Annual Report 23-24, Chapter 3, November 8.

McGuire, Patrick, Goetz von Peter and Sonya Zhu (2024), International finance through the lense of BIS statistics: residence vs nationality, BIS Quarterly Review, March.

Securitisation removes credit risk from bank balance sheets. In a true-sale transaction, loans are sold to a separate entity which issues bonds to investors. In a synthetic transaction, the assets remain on the bank’s balance sheet and only their inherent credit risk is passed on to a vehicle which again may issue bonds to investors. For more details, please see Walther, Ursula (2024), European securitisation market – ready for a comeback? Deutsche Bank Research, Focus Germany, August 19.

Underlying true-sale securitisation is less concentrated and more evenly distributed across Europe, as data on the country of collateral shows.

This section is based on market value unless indicated otherwise.

Book value.

See https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/implement/app/html/index.en.html#cspp and https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/implement/pepp/html/index.en.html.

Draghi, Mario (2024), The future of European competitiveness – A competitiveness strategy for Europe, September 9.

Letta, Enrico (2024), Much more than a market, April 18.

See Hallak, Issam (2024), Capital markets union: Overview and state of play, Briefing, European Parliamentary Research Service, February 8.

European Commission (2022), Proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council harmonising certain aspects of insolvency law, December 7.

For more information, please see https://finance.ec.europa.eu/capital-markets-union-and-financial-markets/capital-markets-union/capital-markets-union-2020-action-plan/action-9-supporting-people-their-retirement_en.