Ever since its foundation, the European Union has struggled to develop a collective “European identity”, while being exposed to the challenges of globalisation, financial disturbances, migration, the Brexit, and the corona virus. However, the hitherto unimaginable Russian inroad on neighbouring Ukraine is about to spur a new wave of solidarity. The present analysis underlines the added value of European integration, which is particularly cherished in times of crisis. However, this should not obscure the differences in political history, economic structures, and diverging challenges in the member states. Notwithstanding the Ukraine crisis, the idea of a full-fletched political union is still a long way off, and it is therefore worth aiming for second-best solutions, such as some form of differentiated further integration. The ongoing Conference on the Future of Europe offers an opportunity to evaluate such concepts, including a major revision of the EU’s security strategy.

Since 24 February 2022, when Russian military forces began to attack the independent republic of Ukraine, much of the democratic world closed ranks in support of preserving the statehood of Ukraine. The Russian assault has immediately provoked heavy economic sanctions on the Russian Federation and its governing elites. Within the European Union, the diverging national interests were put aside in favour of joining the widely accepted goal of frustrating the Russian move and bringing the aggression to an early halt. For the EU, this is a new experience which outshines the often niggling controversies among member states in the past decades. The aggression generates another grave episode in a cascade of crises the Community has had to overcome since the beginning of the 21st century. Following the highlights of euro introduction and eastward expansion, the EU had successively to struggle with the global financial crisis (2008/09), the euro crisis (2010-2012), the refugee and migration crisis (2015/16), the steps towards Brexit (2016-2020) and the corona crisis which spread across the world from 2020.1

As a result, an identity crisis has gradually built up in the EU, which shows that the integration structure does not stand on an immovable foundation but must continuously be justified and, if necessary, adapted to new developments. The successive enlargement of the EU from the original Six to up to 28 member states has increased the spectrum of political opinions and the heterogeneity of economic structures such that the overall integration process was on the verge of running aground. A painful consequence was the Brexit referendum and the departure of United Kingdom from the EU by January 2020. As a result, the global importance of the EU as a leading economic bloc and as a political counterweight to American, Russian and Chinese power interests has shrunk. The bloody conflict in Ukraine exemplifies once more, still having in mind the 1990s with the breakup of Yugoslavia, the incapability of the EU to warrant peace on the continent without having to rely on the US military umbrella. How has the EU coped with these crises and what can be expected for the future of the Union?

The global financial crisis of 2008/09 first reached the EU as an external challenge, only to penetrate, from 2010 onwards, into a full-fledged crisis of the euro system. To cope with it, the much-scolded austerity policy with tight fiscal and monetary stances was pursued from 2012 onwards. Proponents have regarded this policy as inevitable, while opponents demeaned it as a faulty “neoliberal” construction with unforeseeable economic and social damages. In fact, an instant fiscal brake was unavoidable for some problem countries in order to preclude the collapse of financial markets and of government activities. This holds in particular for countries with heavy dept service in foreign currency. The rescue packages put together by the Eurogroup (with inputs from the International Monetary Fund) did provide the intended temporary support, although the consequences and successes were quite different in the program countries concerned. In terms of real GDP per capita, Greece, Spain and Ireland were hardest hit in the short term: in 2019 (i.e. before the onset of the COVID-19 crisis), real GDP per capita in Greece was still 21% below the pre-crises level of 2007 and it has dropped further during the pandemic.

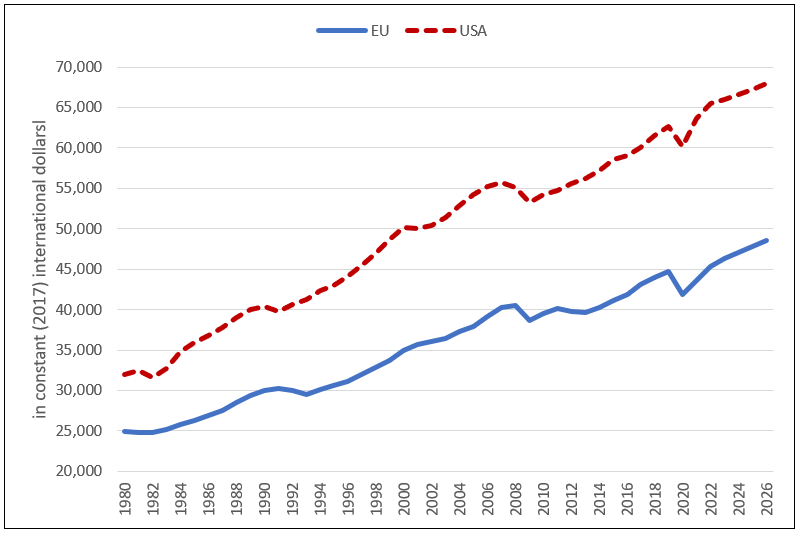

Apart from the adverse income effects of fiscal austerity, the euro crisis has precipitated important impulses to the European integration process. To provide financial assistance for structural reform programmes, the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) was established in 2010, followed by the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) in 2012. To complement the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and the internal market, important steps were taken to establish a banking union (for the supervision and resolution of commercial banks) and a capital markets union (to create a single market for financial capital), both still remaining incomplete. A decisive element of rescuing the euro system from continuous disturbances was the expansionary policy of the European Central Bank (ECB), most effectively communicated by president Mario Draghi’s statement on 26 June 2012 to provide liquidity “whatever it takes”, ensued by the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) programme. However, the EU has failed to achieve one of its major overall goals, envisaged at the turn of the century in the Lisbon Agenda: to put the EU on a path to become, within a decade, “the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world” (European Council, 2000). The main focus was on closing the gap vis-a -vis the USA with respect to the level of real GDP per capita, a goal the EU has evidently failed: When measured in purchasing power parities, average real incomes in 2000 were 43% higher in the US than in the EU, in 2010 the gap was still 37% and in 2020 again 44% (Figure 1). As a consequence, adjustments were made in 2010 when the Europe 2020 Strategy redefined the overall goal as achieving a “smart, sustainable and inclusive growth”, thereby extending the spectrum of targets from per capita income to total welfare, where the EU was seen be much better off.

Figure 1: Real GDP per capita (purchasing power parities in constant international dollars)

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook database, October 2021.

Have more than half-a-century of integration efforts resulted in a forged collective European identity? The rapid expansion of the EU beyond the original Six and the associated economic advantages experienced in all member states seem to provide a clear affirmative answer. But this is contrasted by the inevitable increase in the heterogeneity of the Union, and all the integration benefits cannot disguise the considerable headwinds the EU has to tackle with especially in crisis times.

The concept of “European identity” appears officially for the first time in the documents prepared for the Copenhagen summit in December 1973, which emphasised the “common heritage” of the then nine member states (see, e.g., CVCE, 2013). At that time, collective European identity was viewed as compatible with preserving the rich variety of national cultures and was later on expressed by the EU’s motto “United in diversity” (introduced in 2000). The precarious relationship between diversity and unity has not remained unchanged over time. The need for Union-wide activities tends to increase in turbulent times such as the euro crisis and the corona pandemic. This would also have been the case during the migration wave of 2015 but was brushed aside by short-sighted national interests. Over the years it has become evident that solutions to migration and asylum issues require coordinated efforts on EU level. Actual steps have remained scarce and have mostly occurred at the intergovernmental level rather than through Treaty changes.

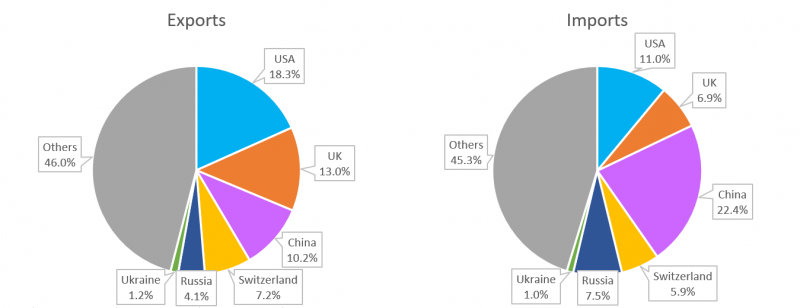

However, European identity is currently receiving a strong boost from the Russian raid on Ukraine. The economic sanctions against the elites around the Putin regime have been unanimously supported by all EU states, although Russia is also quite an important trading partner of the EU: it is fifth-largest in merchandise exports (mostly machinery, vehicles and chemicals) and third-largest in merchandise imports (mostly oil and gas and other raw materials). The Ukraine is associated to the EU through a concessionary agreement which came into force in September 2017. The EU’s trade volume with the Ukraine amounts to some 1.1% of total trade (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Merchandise Trade of EU27 in 2021 (excluding intra-EU trade), top 5 partners and Ukraine (in %)

Source: Based on Eurostat (2022), Russia-EU – international trade in goods statistics, February. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?oldid=317232#Recent_developments

As an immediate consequence of the Russian aggression, the cornered Ukraine government has hastily applied for EU membership under a “new special procedure” to shorten lengthy negotiations. In parallel actions, such applications have also arrived from Georgia and Moldavia. Within the EU, discussions have started on how to strengthen the Union’s military defence. Even in the non-aligned countries Finland and Sweden and in neutral Austria closer links with NATO are being explored. The Temporary Protection Directive (2001/55/EC), originally introduced to manage the Kosovo crisis, will for the first time ever be invoked and entitle displaced Ukrainians to move freely within the EU for at least one year (later extendable) including the possibilities to work, to attend schools and to obtain social benefits.

Today, the European identity, even if still unfinished, is to be seen as the antithesis to the ideas of the radical right-wing populists in Europe and their repudiation of further EU integration. Their understanding of collective identity building is virtually confined to national components as the emotional basis of society. These groups have received increasing public support through their aggressive canvassing against possible threats from massive immigration. According to their view, immigrants not only carry with them extrinsic cultural and religious influences, they also potentially endanger incomes and jobs of indigenous people. Only the nation state would be able to effectively counteract such developments, while an asylum-friendly EU would just provide a stage for fruitless debates on the distribution and integration of refugees.

As an immediate consequence of the migration wave, the range of political goals in the EU narrowed dramatically, to focus chiefly on foreign infiltration. The related conspiracy myths spread faster and more persistently than the less sensational facts of everyday life. Europe was caught unprepared by immigration pressures and had no structures ready to deal with them. The hastily taken defensive measures against the migration pressure (such as “closing the Balkan route”) overwhelmed the asylum systems of the landing states, which failed to effectively control irregular migration. In all countries affected, the political spectrum has since consistently moved from the centre to the right, to a pronounced stance against immigration in general, but also against the refugees under human rights protection. A meaningful solution would require the effective securing of the EU’s external borders, but this is not foreseeable given the divergent interests of the member states. Therefore, countries have attempted to solve their problems individually by (re-)establishing national borders and erecting fences, even against the rules of the internal market. In the meantime, the corona crisis has temporarily pushed the refugee problem out of the media headlines. The Russian war in Ukraine has brought about a temporary hype towards assisting displaced persons from a neighbouring country with a similar culture.

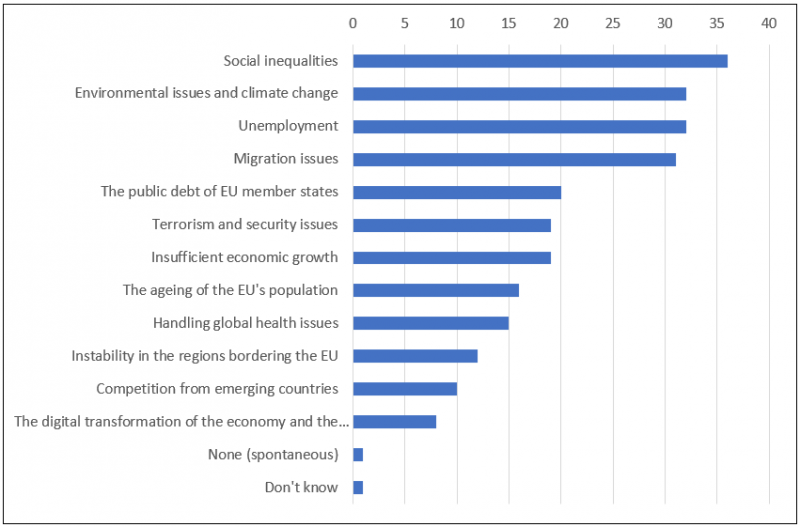

Between 2015 and 2019, Eurobarometer surveys often identified the wave of migration as the most important problem facing the EU. During the pandemic, immigration was replaced by fears about health and the economic situation, and has lately given way to social inequalities, environmental issues and unemployment (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Main challenges for the EU

Question QA16: Which of the following do you think are the main challenges for the EU? (Max. 3 answers)

Source: Special Eurobarometer 517, September/October 2021. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/7fc24136-8569-11ec-8c40-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

Although views with pronounced nationalist tendencies are gaining strength, in opinion polls economic integration is still seen as a clear advantage. However, significant design flaws in the constitution of the Union as well as gaps in substantive positions make it difficult for an overarching European idea to emerge. One prominent example for diverging interests of the member states has for many years been the futile attempt to remedy the glaring deficiency in the EU’s social policy. While social issues have traditionally been a competency of the member states, they were incorporated into the primary body of EU law by the Treaty of Amsterdam (Article 151 TFEU) and made more concrete in November 2017 by the “European Pillar of Social Rights”. The corresponding action plan was publicised by the European Commission (2021). Unwarranted little attention has also been placed on the climate change and on defence.

One of the frequently cited shortcomings of the EU’s constitutional design has been the democratic deficit of its representative institutions which manifests itself in the lack of pan-European political parties. Community issues are thus presented, discussed and assessed from a predominantly national perspective. The further development of the EU as a community is hindered by the principle of unanimity in the Council, which gives each member state the right of veto on important materials. The founding treaty of the European Economic Community had provided for the termination of this rule by 1966 and replacing it by a qualified majority, but this change failed due to a French veto. Today – in view of the now greatly enlarged number of member states – it would be even more appropriate to restrict unanimity to a few fundamental issues and replace it by qualified majority in purely operational and financing questions. The opaque jungle of competencies between the member states and the EU level as well as the blurred division of tasks at EU level between legislative and executive powers may also be qualified as a serious system deficiency.

The perceived overregulation by “Brussels” is also often lamented, although the responsibility for ever more Community rules rests predominantly with activities of pressure groups in the member states. From the point of view of right-wing populists, the EU is considered a “project of the elites” which provides little say for “the people”. Another flaw may be perceived in the virtual neglect of universal citizenship in the EU. Although the idea is rooted in the Enlightenment of the 18th century, which is regarded as an important intellectual basis for European integration and its value system, Union citizenship has not yet caught on. It was introduced in the Maastricht Treaty of 1992 to complement (not to replace) national citizenship, but has so far hardly had any effect on identity formation.

The project of the economic and political integration of Europe has long been criticized by left-wing commentators as being deficient with respect to social and environmental standards. Some of them oppose further globalization which they deem responsible for depriving the already poor (Sen, 2002), others relate economic integration to a policy of realising neoliberal ideas. Currently, however, the European integration project is more fundamentally questioned by right-wing nationalists, as many of them vilify the established institutions of representative democracy. They reject the EU in its current form because it competes with national sovereignty and identity. From this controversy it can be learned that the EU was by no means founded on the basis of common liberal values but rather on past experiences that a lack of cooperation and open dialogue may lead to destructive wars (Bet-El, 2018).

In the political reality of Europe, populism is understood as a movement against the ruling groups, irrespective of their democratic legitimisation. Populism can appear as an ideology (political model), as a style (type of political discourse) or as a strategy (mobilisation and organisation), and there are hardly any restrictions regarding political party directions (Gidron and Bonikowski, 2013). Some of the claims of national populists (fight against capitalism and elites) could also come from parties far left. Left-wing populism often aims at the inclusion of disadvantaged groups, while right-wing populists usually propagate exclusion in order to keep unwanted groups away from the established social system. The electoral successes of the latter can mainly be traced back to fears of a creeping change in the cultural order of values (family structures, religiosity), which in the short to medium term may be reinforced by economic shocks (Rodrik 2019).

It is not uncommon for the intentions pursued by right-wing populists to collide with the democratic rules of the game, which, in the case of the EU, has materialised as a symbiosis of representative democracy and constitutional liberalism (Zakaria, 1997). If populism is just a method of making political content palatable to the electorate, this may not result in a contradiction to liberal democracy. However, right-wing populist and extremist movements often hide their authoritarian core behind the claim to act in the interests of “the people”. Müller (2016) sees right-wing populism not so much as a fight against the elites as against pluralism, which is also a fundamental element of liberal democracy. Taggart (2012) argues that, even if national populist movements question liberal democracy, they should not be demonised. Rather, the problem areas addressed by them should be taken up by liberal-democratic politics with the aim of developing joint solutions, especially in the topical questions of immigration, multiculturalism and European integration.

The Brexit referendum of June 2016 validated, by a thin majority of British voters, the UK’s drop-out from the EU. It was the culminating event of a long-standing struggle with Community institutions, eventually fuelled by internal populist activities in the UK, which took no regard of the adverse economic consequences for both the UK and the remaining EU27. The result of the referendum mirrors the various British aversions against the European continent as well as the British yearning for the rebirth of a long-gone empire.

One of the roots of the Brexit may be traced to Rodrik’s (2011) “globalisation trilemma”, which demonstrates the possible frictions between a fully globalised world (or within the EU a fully integrated country), maintaining national decision making, and preserving democratic rules. Sampson (2017) takes up this idea and interprets Brexit as a democratic reaction to the creeping loss of British sovereignty during the gradually advancing integration into the EU. Conversely, this means for the EU that an ever-deeper integration of the member states could conflict with maintaining the traditional institutions of national representative democracy. For a democratic Europe it follows that either a collective European identity needs to develop and dominate the national identities, or that the supranational component of the EU must gradually be reduced. Otherwise, one should reckon with further exits from the EU.

Empirical studies on the macroeconomic consequences of Brexit show that welfare losses are recorded on both sides of the channel, although the immediate losses are higher in the UK than in the EU27. More serious distortions can be ruled out because adjustments have already occurred in the years since the referendum and the new bilateral trade agreement has cleared the way for mutually beneficial future relations. However, it still remains to be seen whether the British are ready to fully implement the agreement with regard to Northern Ireland. With respect to merchandise trade, the UK is the EU’s second-largest partner in exports and third-largest partner in imports (see Figure 2 above). Since the turn of the century, the trade balance has for many years shown a surplus for the Union. The Russian aggression on Ukraine has subdued the bilateral animosities between UK and EU and both sides have joined forces to sanction the Putin regime.

Some support for European solidarity has developed in the wake of the corona pandemic which needed trans-border cooperation to be curbed. Contemporaneously, rising uncertainty about the medical consequences of a COVID-19 infection as well as the bumpy start of support measures have opened another vantage point for the conspiracy myths of right-wing populists. Mask refusers, lockdown opponents and anti-vaxxers found a way to ally with those who had run into health, psychological or economic troubles as a result of the crisis.

However, without core health competencies, the Union’s role in curtailing the pandemic was rather limited from the outset. When the corona pandemic began to spread, the much-deplored system of internal border controls, which had been established during the migration crisis, was reactivated. Although this did not prevent the spread of the virus altogether, national protective measures could quickly be implemented without lengthy coordination at EU level. When the corona crisis surfaced, the EU was still occupied with resolving previous crises, and a newly installed European Commission was about to implement their plans.

Some aspects of the pandemic are mirroring the earlier crises. The lockdowns and border closings are reminiscent of the refugee crisis, and the enormous state aid reminds us of the euro crisis. In contrast to the financial crisis, when economic imbalances acted as triggers, such imbalances are now a consequence of the pandemic. As compared with the refugee crisis, where migrants could be counted by hard numbers, the creeping collapse of the health system during the pandemic has been much less palpable.

Some of the political and economic rifts which over the years have arisen between EU countries were briefly covered up by the COVID-19 shock. But the chasm loomed again when the emergency measures appeared to end the pandemic. In addition, the corona crisis itself triggered new disputes, concerning the approval and distribution of vaccines and the border closings that were in conflict with the internal market. Such quarrels demonstrated once again the limited perspectives to further deepen integration in Europe.

In order to limit the economic damage caused by the pandemic, enormous financial resources had to be furnished at national and EU level to stimulate growth, to curb unemployment and to mitigate asymmetric distribution effects. In the corporate sector, the main issues were a (partial) compensation of income losses and the possibility of targeted investments in order to eliminate existing structural weaknesses and prevent new ones from arising. Politicians were faced with the challenge of allocating the limited funds on vital and capable projects.

As the pandemic spread, the EU was negotiating the medium-term EU budget. Added to this was the need to provide financial aid at EU level to complement national efforts of preventing the collapse of entire economic sectors. This resulted in a package of two central components, the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) 2021/27 and the temporary recovery instrument “Next Generation EU” (NGEU) with a total volume of 1,824.3 billion euros (at 2018 prices). The EU will refinance the 750 billion euros of the NGEU program in the long term (until 2058) through common debt instruments with joint liability of all member states (“corona bonds”). The projects are defined by the National Recovery and Resilience Plans (NRRPs), which are monitored within the framework of the European Semester based on country-specific recommendations of the Council. This post-crisis rebound will thus again be dominated by the narrow perspectives of the member states, while common goals2 are only taken into account on the financing side. The overarching goal would have better been served if all projects had been selected according to Community criteria by an independent body (reporting to the European Parliament).

In every community, solidarity proves to be a particularly desirable behaviour in crisis times. Many observers rate the solidarity-driven fiscal measures of the EU to stabilise the pandemic-related shortfall in demand and production as a remarkable success. However, criticism has been voiced concerning an inadequate utilisation of the allocation function of fiscal policy. The NRRPs reveal that substitution effects are likely for many national projects which were in preparation beforehand and are now just co-funded by the Union. In addition, there is no clear separation between purely private activities with individual profit expectations and public sector tasks justifying joint public/private financing. With regard to the distribution function of public support, Fuest (2021) points out that the funds from NGEU do not primarily provide compensation for damage from the corona crisis. They rather redistribute from richer to poorer countries (as measured in terms of GDP per capita) and thus only complement the traditional cohesion policy. Despite all the criticism of the complex support programs, it must be recognised that in times of crisis the EU and its decision-making bodies have proven sufficiently flexible to cross previous red lines to optimise welfare in the community.

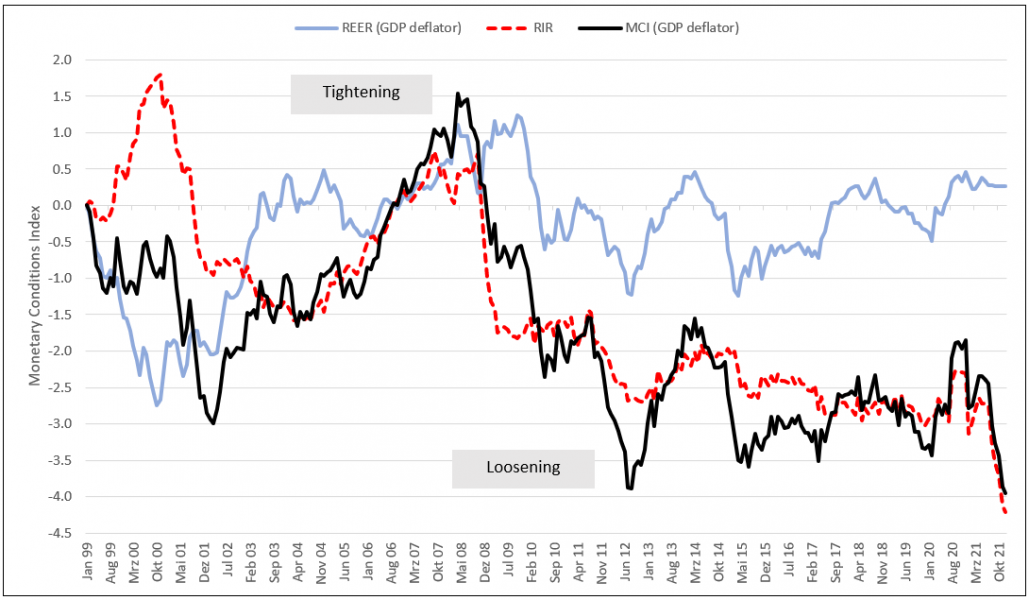

In order to maintain the function of the banks as financial intermediaries and risk carriers during the corona crisis, the ECB has adopted a series of easing measures since spring 2020. As a result, the liquidity in the banking sector has increased massively, so that at the beginning of 2021 it was many times higher than during the euro crisis. Private non-banks reacted by a drastic rise in the savings rate and a slight increase in cash holdings. This is also reflected in the Commission’s Monetary Conditions Index (MCI) which currently matches the extremely loose conditions of mid-2012 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Monetary Conditions Index (MCI)

Source: European Commission, Monetary Conditions Index. https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/indicators-statistics/economic-databases/monetary-conditions-index_en

Note: The Monetary Conditions Index (MCI) is calculated as a linear combination of the short-run interest rate and the exchange rate. REER is the real effective exchange rate of the euro, RIR the real short-term interest rate.

Overall, the expansive monetary measures prevented the other aid policies at European and national level from reaching their funding limits. The tensions in global supply chains, originating from the measures to contain the pandemic and now exacerbated by the sanctions against Russia, are contributing to rising production costs which are prone to trigger an inflationary process. The monetary authorities are well advised to prepare a gradual reduction in excess liquidity. In the medium to long term, the corona crisis will probably also require a reassessment of global value chains to secure “strategic” productions in the EU. By this way, however, neither should national protectionisms be furthered, nor essential productions in developing countries (further) be impeded (e.g. via export subsidies for EU agricultural products).

The COVID-19 measures would have been an excellent opportunity to tackle structural adjustments in the EU budget that have long been overdue and to combine them with reinforcing the principle of subsidiarity. Just as with cohesion policy, a relocation of competences to the national level would also have been possible in the agricultural sector: Pillar 1 of the Common Agricultural Policy (income support and market management) could well be operated exclusively at the national level. As a compensation, Community-relevant issues of climate change, pandemic management and the humane treatment of refugees are anyway due to be ceded to the EU level.

Another problem, already simmering for some time, surfaced during the negotiations to finance adequate measures for alleviating the economic consequences of the corona crisis: the due respect in all member countries for the rule of law. In order to examine allegations of violations of this fundamental EU principle and, if necessary, to take appropriate sanctions, the Commission has initiated proceedings against Poland and Hungary in accordance with Article 7 TEU. Ultimately, a persistent violation of such principles can only be resolved by either having a violating country leave the EU or by creating a second tier of membership where periphery countries hold limited rights and obligations. Regardless of the economic and social differences in individual member states, it would be easier to identify with the Union, if not all of them had to go through each and every integration step. Ohr (2017) emphasises the achievements of European integration so far, in particular the European internal market, but warns about jeopardising the willingness to integrate by overarching demands for an “ever closer union”.

Have the recurring crises strengthened or weakened the European integration process? Is the EU on the way to “differentiated integration” or “differentiated disintegration” (Tekin, 2016), if not to dissolution at all? The crises of the past one and a half decades have underscored the limits of a largely abstract European identity. As the EU has up to now only developed rudimentary Community institutions, the meaning of “Europe” cannot easily be demonstrated to the national populations. Election-dependent national politicians cannot be expected to endanger their own positions, it is thus inconceivable that, without external pressure, in the foreseeable future a constitutionally-adopted decisive strengthening of the EU level will emerge. This is exemplified by the Ukraine crisis which has brought about an astonishing solidarity in favour of sanctioning the Russian assault. In the long run, a further deepening of the EU’s integration goal can only be attained if the democratic legitimacy of EU institutions is strengthened and the separation of political powers is more firmly established. In order to make the voters sufficiently familiar with European issues and viewpoints, political parties are required that are not mainly entangled in national problems but can argue and advertise on a European basis.

In order to maintain the level of integration achieved so far and to liven it up, the principle of subsidiarity laid down in Article 5 (3) TEU should be respected more consistently than hitherto. In return, member states should be urged to show more solidarity with community issues. In the resulting system, pan-European goals would have to be defined at the EU level (top-down), but implementation should occur at the national and regional levels (bottom-up) where the contact with the people concerned and their needs is established and maintained. Evaluation of the results would then again be conducted uniformly at the European level.

The cascade of crises the EU has faced over the past decade and a half has not only unearthed the drawbacks of heterogeneity but also tended to strengthen a sense of togetherness among Europeans. This could be further strengthened, if the questions and concerns raised by the sceptics of European integration were taken up by the current Conference on the Future of the EU which could design a model for the peaceful coexistence of different countries with non-congruent cultures.

Based on a ruling by the German Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht, 2009), the EU is not a federal state, but remains a confederation of sovereign states (Staatenverbund) with some delimited aspects of a federal state. Not only legally, but also politically, the approach of forming a united Europe which is globally represented by one voice has not materialised. In relation to the world, Europe is economically a great power but politically it is still fragmented. In international bodies (United Nations, International Monetary Fund, World Bank, etc.) most often only its larger member states are visible. This weakness has still increased with the UK’s exit from the EU and is only temporarily mitigated through the solidarity with Ukraine.

The EU is a deeply political project with enormous economic potential, but it has not proceeded far beyond its economic beginnings. The successive crises have strengthened the core of the EU, but at the same time they have sharpened the differences between the member states. The ardent supporters of full political integration see this as the optimal long-term goal for the continent. For realists, this objective seems so far away that it is worthwhile to aim for second-best solutions. Some of them, and ways to make them come true, have been discussed here.

European Commission (2012), Public Finances in EMU 2012, European Economy 4/2012, Brussels.

Bet-El, Ilana (2018), “The EU has lost the liberal plot”, Friends of Europe, 3 July.

BVerfG (2009), Judgement of the Second Senate, Bundesverfassungsgericht, 2 BvE 2/08 -, paras. 1-421, 30 June.

CVCE (2013), Declaration on European Identity (Copenhagen, 14 December 1973), CVCE.eu de l’Université du Luxembourg, 18 December.

European Commission (2010), Europe 2020: A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, Communication COM(2010) 2020 final, 3 March.

European Commission (2021), The European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan, Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

European Council (2000), Presidency Conclusions, Lisbon, 23 and 24 March.

Fuest, Clemens (2021), The NGEU Economic Recovery Fund, CESifo Forum, 22(1), January: 3-8.

Gidron, Noam and Bart Bonikowski (2013), Varieties of populism: Literature review and research agenda, Harvard University, Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Working Paper Series 13-0004.

Handler, Heinz (2021), Krisengeprüftes Europa: Wie wir die Solidarität in der EU stärken können, Wiesbaden (Springer Verlag), November. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-658-35240-0.

Müller, Jan-Werner (2016), Was ist Populismus?, Suhrkamp (Berlin).

Ohr, Renate (2017), Solidarität kann man nicht erzwingen, Interview von Bernard Marks, Göttinger Tageblatt, 10 June.

Rodrik, Dani (2011), The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy, New York – London (W.W. Norton).

Rodrik, Dani (2019), What’s driving populism?, Project Syndicate, 9 July.

Sampson, Thomas (2017), Brexit: The Economics of International Disintegration, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(4), 163-184.

Sen, Amartya (2002), How to Judge Globalism, The American Prospect, 5 January.

Taggart, Paul (2012), Populism has the potential to damage European democracy, but demonising populist parties is self-defeating, London School of Economics, LSE Blog, November.

Tekin, Funda (2016), Was folgt aus dem Brexit? Mögliche Szenarien differenzierter (Des-)Integration, Integration, 39(3), 183-197.

Zakaria, Fareed (1997), The rise of illiberal democracy, Foreign Affairs, 76, November/December, 22-43.

For an in-depth analysis, see Handler (2021).

The six pillars of the Recovery and Resilience Facility are: green transition; digital transformation; smart, sustainable and inclusive growth and jobs; social and territorial cohesion; health and resilience; and policies for the next generation, including education and skills.