Despite political ambitions and economic arguments, cross-border consolidation in the European banking sector has remained limited. Moreover, it is unlikely that Europe will witness a strong increase in such consolidation in the near future. In this paper I provide five arguments why this is the case. The strong home bias in services provision is a structural feature that may be hard to change. A strong focus on capitalisation and enhanced risk management, in particular after the coronavirus crisis, will lower the appetite for international consolidation. Regulatory divergence and lack of regulatory level playing field are major barriers too. Moreover, banks are more likely to focus on improving their position and performance on their domestic markets. Finally, cross-border consolidation may not be a priority in a sector strongly focused on innovation and digitalisation.

It seemed to be written in the stars. A turbulent decade after the financial crisis, many still expect a strong wave of cross-border consolidation in the European financial sector. Above all, European policymakers have been dreaming of a giant step forward in the financial integration of Europe through the completion of the European Banking Union and the creation of a European Capital Markets Union. Both ambitious integration projects are built upon the idea that banks and other financial institutions consider the European market as their home market, in particular inside the euro area. Hence, cross-border consolidation would be an obvious part of any European-wide strategy. The development of truly integrated cross-border financial service providers would obviously strengthen the perspective of an integrated European financial environment, a cornerstone of full-fledged political integration in Europe. Moreover, it would strengthen European financial institutions in the global economy by sheltering them from increasing import competition caused by the international expansion of global financial conglomerates, mainly coming from the US and China. Additionally, a broader European base would enhance European financial institutions’ growth prospects outside the European borders.

Apart from geopolitical aspirations, cross-border consolidation in the European financial sector makes economic sense too. Through consolidation, financial institutions may benefit from economies of scale. In particular, in a period of low profitability among European banks, any strategy that contributes to reducing banks’ cost-income ratios is welcome. At first glance, there seems to be an enormous scope for scale effects given the fragmentation of the European financial sector, without jeopardising the free and fair competition in the market. Moreover, at the current stage of the European business cycle one observes a growing appetite for mergers and acquisitions throughout the economy. Consolidation would definitely not be a feature unique to the financial sector. Finally, financial institutions would be able to geographically diversify their activities, making them less sensitive to country-specific shocks like the ones Europe suffered from during the global financial crisis and the European sovereign debt crisis. Hence, not only would banks benefit, but general macroeconomic stability would be improved too.

Despite these advantages, the expected trend in cross-border consolidation in the European financial sector has yet to materialize. In this contribution I put forward five arguments why this has been the case and why it remains unlikely in the near term. I illustrate these arguments with some empirical evidence. Together these arguments aim to provide insights into why cross-border consolidation in European banking remains limited today and will most likely remain so in the near future.

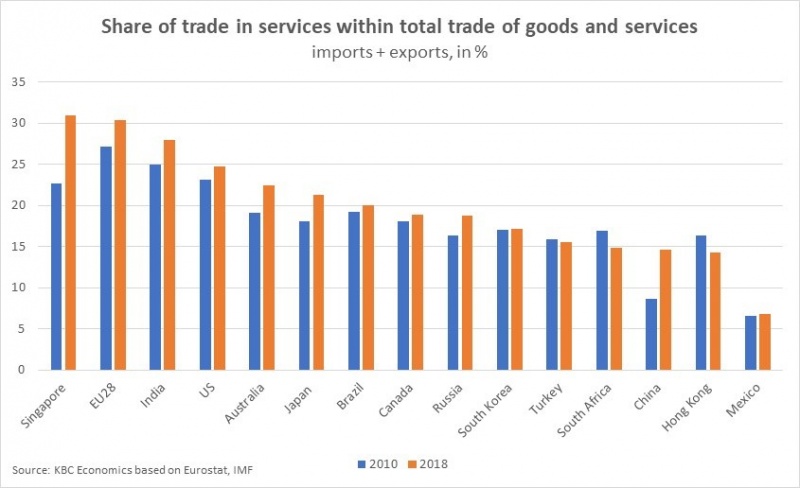

Zooming out from the financial sector, and broadening our perspective to cross-border services activities, one can notice in Figure 1 that the share of services within total trade of goods and services is hardly growing and remains very limited. For the EU28, this share reached approximately 30% in 2018. With that percentage, the EU is among the most internationally oriented services providers in the world. Hence, the lack of international provision of services is not a distinctive feature of the financial sector, but rather a common feature across services activities.

Figure 1.

Despite many international and European initiatives to open up services to international trade, there remains a strong home bias in services provision. Many reasons have been put forward in the literature, including the limited tradability of services, the need for face-to-face contact, and regulatory barriers to trade. In particular for the European financial sector one should acknowledge the complexity of regulations (see further) and the market-specific nature of various financial products. These features raise barriers to the internationalisation of financial services. Hence, they limit the growth prospects for providing financial services beyond the home market(s) as well as the attractiveness of cross-border mergers and acquisitions.

In general, consolidation starts at the moment firms can afford such operations. Macroeconomically speaking, the number and value of mergers and acquisitions go up after several consecutive years of economic growth and often near the peak of a business cycle. As noted before, one doesn’t currently notice much appetite for cross-border consolidation in the European financial sector. This is not due to the macroeconomic environment, which is relatively favourable despite the recent global growth slowdown. It is rather European banks’ low profitability in combination with a priority focus on sufficient capitalisation and enhanced risk management.

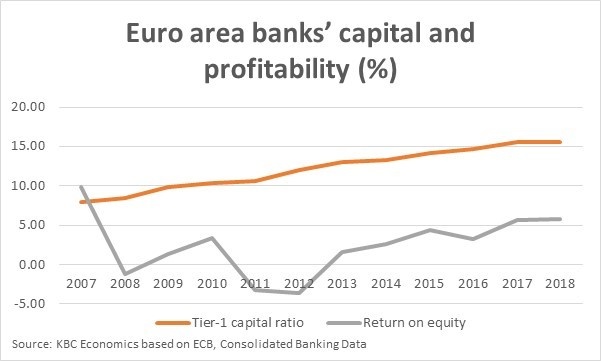

The average return on equity for European banks equalled only 5.76% in 2018 (see Figure 2). Despite the gradual rise in average profitability in recent years, the current level is still far below the pre-crisis profitability achieved by European banks. Though low profitability could be an argument for more consolidation, that does not seem to be the case in Europe today despite many calls by regulators. The latter could be explained by the strong focus on banks’ capital bases as buffers for adverse shocks. The average Tier-1 capital ratios in Europe continued to rise to 15.57% in 2018. Clearly, banks prefer to strengthen their balance sheets rather than to engage in international expansion. Bank supervisors emphasize the need for further capitalisation too. This strategic reaction makes sense but points to a contradiction. Although more consolidation would boost the sector’s profitability and contribute to financial stability, the strong regulatory focus on financial stability risks makes consolidation far less attractive.

Figure 2.

Obviously, not all European banks suffer from low profitability or capitalisation issues. One could argue that the profitability differences across Europe are fertile soil for consolidation as more profitable banks could acquire less profitable banks, allowing the new entities to benefit from economies of scale. But even the more profitable banks in Europe may be worried about putting their current profitability at risk by geographical expansion. In general, banks have invested in enhanced risk management. Their general risk appetite is substantially lower than before the financial crisis. Hence, acquiring other banks may increase their exposure to, inter alia, historical credit risks. This risk may be higher in case of foreign acquisitions, as banks are more familiar with the economic and company-specific situation in their home market(s).

The advantages of scale effects and synergies are often limited by international regulatory divergences, even within the euro area, that cause substantial costs to banks. In practice, banks, even systemic banks supervised by the ECB, have to listen to many masters. National regulators differ from each other in their way of working as well as their approach to banking supervision, not least due to cultural and linguistic differences. Consequently, there isn’t much scope for synergies in risk management activities. As long as banking regulations as well as other regulations (consumer protection, fiscal rules, etc.) are not fully harmonised across Europe, or alternatively, as long as banking regulations in particular remain the joint responsibility of European and national regulators, international regulatory differences will remain an important barrier to cross-border consolidation in European banking.

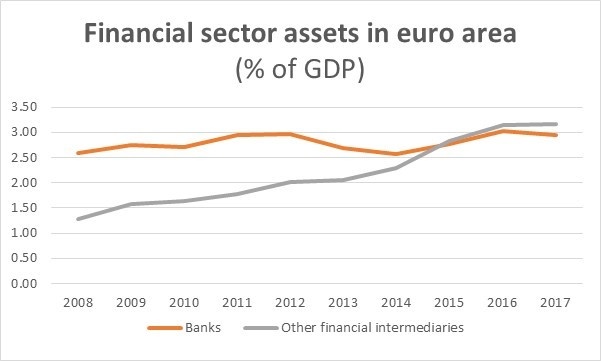

Apart from regulatory differences, incumbent European banks are also confronted with the absence of a level regulatory playing field. Many new financial services, originating from the ongoing intensive innovation wave in the financial sector, benefit from no or limited regulation. Often, FinTechs escape from traditional banking supervision as current regulation is not yet focused on innovative products and services. This creates a discrimination between incumbent and new players. Given the fast rise of alternative financial intermediaries (see Figure 3), this trend has a major impact on dynamics in the European financial sector. In practice, it limits the prospects for cross-European banking consolidation, as the acquisition of foreign banks becomes less attractive in a market environment with intense competition caused by less regulated new players.

Figure 3.

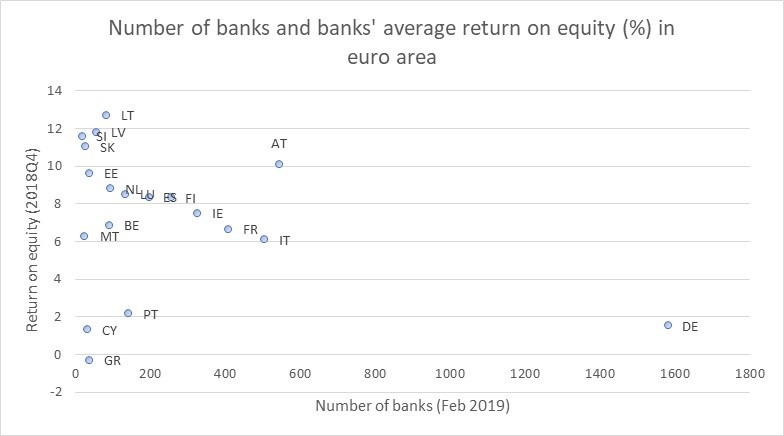

Another reason why European banks are not intensively looking for international expansion opportunities is the prevalence of many potential opportunities at home. Many European domestic markets are still very fragmented, despite previous consolidation, which is closely related to low average profitability (see Figure 4). From a financial stability perspective as well as from a market-logic perspective, domestic consolidation makes a lot of sense and is unlikely to jeopardise the level of competition in the domestic market. Domestic consolidation is much more likely to lead to synergies and is operationally easier to achieve, also for smaller banks.

Figure 4.

In practice, we notice that a substantial part of the recent consolidation in the European financial sector was the result of such domestic consolidation. Some larger operations took place in reaction to the actual or potential collapse of particular banks, often in close cooperation with the regulators. At best, these operations involve foreign banks that are already active in the market. As such, it seems that a domestic ‘clean-up’ of the financial sector is a necessary step before cross-border consolidation will start. Cross-border consolidation becomes a more attractive strategy once banks have a sufficiently strong domestic base in combination with a lowered financial stability risk in the home market. This holds in particular for European countries with a very fragmented banking landscape and numerous banks facing major financial challenges. Italy and Germany are clear examples.

I already pointed to substantial differences in profitability across European banks. Currently, the most profitable banks in Europe don’t engage very actively in cross-border consolidation. At best they consolidate within their current home market(s). Such strategy contributes to further consolidation, but it is far from what policymakers have in mind when dreaming about a substantial wave of cross-border consolidation in the European banking sector.

While merger and acquisition strategies are not overly ambitious at this moment, other strategies stand out. Successful European banks currently rather focus on alternative strategies, including product and service diversification, innovation, digitalisation, ‘beyond banking’ strategies, artificial intelligence and big data analysis, or a combination of these. Investing in such strategies seems to provide a higher return than traditional acquisitions. Although any strategy could combine various approaches, including geographical expansion plans, the latter are likely to complicate the rolling-out of innovative business processes.

Though the prospects for cross-border consolidation in the European banking sector appear to be rather limited in the near future, it cannot be excluded that such consolidation will eventually take place. The most likely scenario would be a merger between two major European banks that triggers a wave of consolidation throughout the entire sector. Such a merger itself could be the result of political aspirations or global ambitions of the banks involved. More generally, one cannot exclude the possibility that some banks start the consolidation train and then other banks jump on just to avoid missing the train. However, the economic rationale for such operations is limited, and therefore the return is likely to be low. The match between partner-banks may appear to be much weaker than expected. Banking history is full of such examples. Unfortunately, we all know the saying… L’histoire se répète…