This article was originally published as a box in the 2025 Euro Area Report (European Commission).

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic and energy crisis heightened risks of income divergences in the euro area. However, real GDP per capita convergence remained resilient, with most Member States recovering pre-pandemic income levels by 2022. Unlike the global financial crisis, recent shocks were exogenous and mitigated by swift national and EU policy responses, including fiscal support and the RRF. These measures helped preserve employment and economic stability, ensuring continued convergence despite temporary disruptions.

The pandemic and the energy crisis heightened risks of income divergences in the euro area and, more generally, in the EU. These shocks led to disruptions that could threaten to widen the gap between the more advanced, resilient, and diversified economies, and those that are more heavily reliant on specific sectors or external energy supplies.

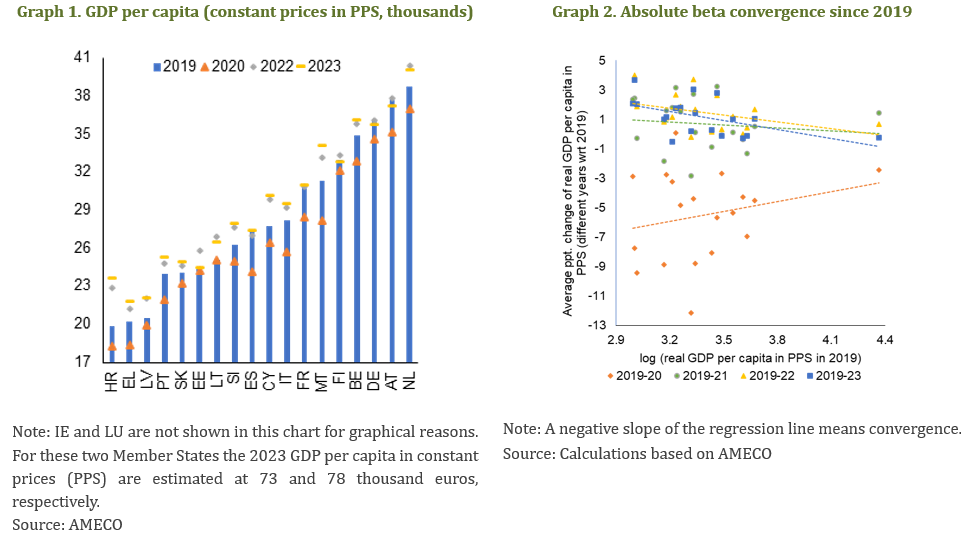

Four years after the onset of the pandemic and two years following the energy shock, convergence in real GDP per capita among euro area Member States does not appear to have been significantly affected. All Member States experienced large losses in income at the start of the pandemic, with losses in real GDP per capita in 2020 ranging from less than 2½% in Latvia, Estonia, and Luxembourg to over 9½% in Greece, Spain, and Malta. However, by the end of 2022, most Member States had recovered their 2019 income levels (Graph 1). Absolute beta convergence estimates1, measured against 2019 income levels, confirm temporary disruptions in 2020 (as shown by the upward sloping curve in Graph 2) but convergence resumed on the back of the 2021-22 recovery. The ensuing energy shock did not lead to further divergences. Convergence in 2023 was driven by faster growth in the south and in some eastern countries associated with negative growth per capita in Germany, Finland, Austria, and Luxembourg.

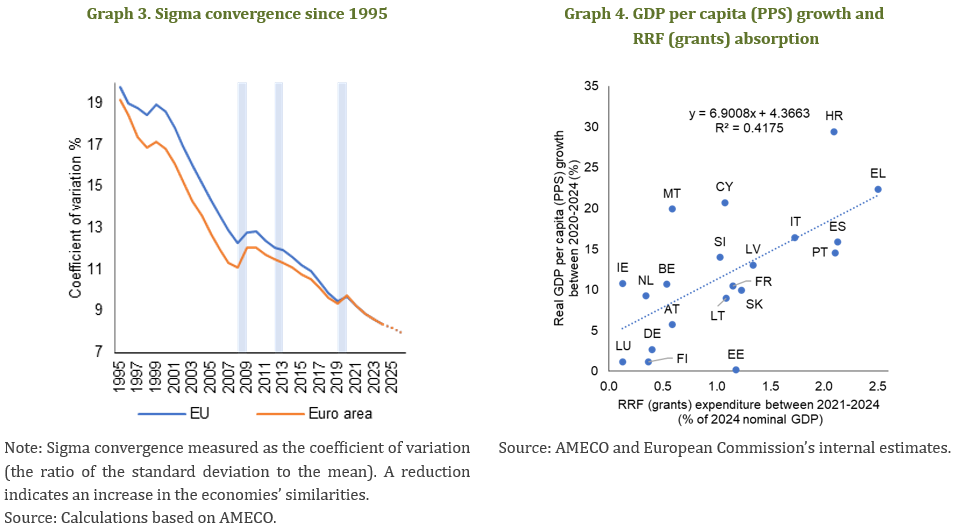

Recent shocks had a more transient impact on convergence compared to the lasting disruptions during the global financial crisis (GFC). The GFC significantly undermined the Member States resilience and economic activity in the euro area as a whole. It took about seven years to return to pre-2008 levels. The temporary nature of the more recent shocks is well evidenced by the dynamics of sigma convergence2 or the coefficient of variation of real GDP per capita (Graph 3). During the GFC, the coefficient saw a large increase between 2008 and 2010 that took around 8 years to unwind. By contrast, during the pandemic in 2020 the increase was relatively small, and it returned to pre-crises levels in 2021, declining further in 2022 and 2023, despite the energy shock3.

The milder impact of recent crises on income convergence in the euro area, compared to previous shocks, was due to the very different nature of the shocks and the different policy responses. The global financial crisis, which emerged in 2008, originated from macro-financial imbalances that had built up for years in several large economies. This led to a prolonged period of adjustment for both the private sector and governments, which was further complicated by weaknesses in the financial systems. By contrast, the COVID-19 and the energy shock were major exogenous shocks, mitigated by national and EU policies. Governments responded to the pandemic and the subsequent energy shock with a range of policy measures cushioning the economic blow and facilitating a swift recovery. The fiscal situation at the beginning of 2020 was much stronger in most Member States than it had been in 2008, creating space for effective policy action. Fiscal policies played a crucial role, with high public spending to support businesses, protect jobs, and sustain household incomes. In the Union, Next Generation EU provided significant financial resources for Member States to invest in their economies. The RRF aimed by design at supporting economic convergence; it proved useful and adaptable to the challenges of the subsequent disruption of energy markets (Graph 4). The SURE instrument also supported relevant institutional changes in several Member States in support of short-time work schemes and similar measures, which helped to keep people in jobs, avoiding unemployment, income losses and long-term scaring4. Finally, several monetary policy measures avoided financial fragmentation and quickly adapted to face the new challenges generated by the inflation spike.

Absolute beta convergence implies that lower-income countries or regions grow faster than richer ones. It is measured by the slope of a regression line between the initial income level and subsequent growth rate. A negative slope indicates convergence, with a steeper slope suggesting a faster convergence rate, as economies with lower initial incomes grow more rapidly than those with higher starting points.

Sigma convergence refers to a reduction in the dispersion of income levels across regions, countries, or groups over time. When measured as the coefficient of variation, sigma convergence indicates a decrease in the relative spread of GDP per capita. In this context, sigma convergence occurs if the coefficient of variation decreases over time, suggesting that the disparities or variations between countries are shrinking, which indicates convergence toward a more homogeneous level.

Beta coefficient estimates based on the 1995-2023 show a relatively mild impact observed after the pandemic and energy shock. This contrasts the steep decline during the three years after the GFC. See Licchetta M. and Mattozzi G. (2023), Convergence in GDP per Capita in the Euro Area and the EU at the Time of COVID-19. Intereconomics (Vol. 58, Issue 1, pp. 43–51)

The SURE instrument is estimated to have supported 31.5 million people and over 2.5 million firms in 2020. See European Commission (2023), European Commission. (2023c). SURE after its sunset: final bi-annual report. COM(2023) 291 final, June 2023.