This Policy Brief is based on NBER Working Paper No. 32316. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the Federal Reserve System, or any of their staff.

In recent years, assets of non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs) have grown significantly relative to those of banks. These two sectors are commonly viewed either as operating in parallel, performing different activities, or as substitutes, performing substantially similar activities, with banks inside and NBFIs outside the perimeter of banking regulation. We argue instead that NBFI and bank businesses and risks are so interwoven that they are better described as having transformed over time rather than as having migrated from banks to NBFIs. These transformations are at least in part a response to regulation and are such that banks remain special as both routine and emergency liquidity providers to NBFIs. We support this perspective as follows: (i) The new and enhanced financial accounts data for the United States (“From Whom to Whom”) show that banks and NBFIs finance each other, with NBFIs especially dependent on banks; (ii) Case studies and regulatory data show that banks remain exposed to credit and funding risks, which at first glance seem to have moved to NBFIs, and also to contingent liquidity risk from the provision of credit lines to NBFIs; and (iii) Empirical work confirms bank-NBFI linkages through the correlation of their abnormal equity returns and market-based measures of systemic risk. We discuss some potential regulatory responses, including treating the two sectors holistically; recognizing the implications for risk propagation and amplification; and exploring new ways to internalize the costs of systemic risk.

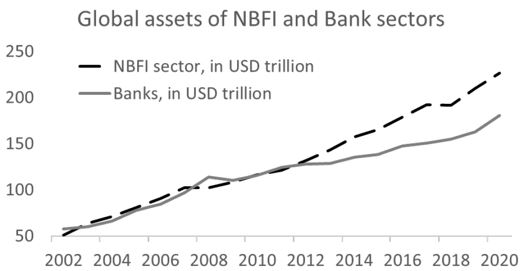

Non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs) have surpassed banks as the largest global financial intermediaries. And yet, most NBFIs continue to be lightly regulated relative to banks for safety and soundness, whether in terms of capital and liquidity requirements, supervisory oversight, or resolution planning. Figure 1 shows, using data from the Financial Stability Board (FSB), that the global financial assets of NBFIs have grown faster than those of banks since 2012, to about $239 trillion and $183 trillion in 2021, respectively. In percentage terms, the share of the NBFI sector has grown from about 44% in 2012 to about 49% as of 2021, while banks’ share has shrunk from about 45% to about 38% over the same time period.

Figure 1: Global Financial Assets of NBFI and Bank Sectors, 2002-2021

Notes: The NBFI sector includes all financial institutions that are not central banks, banks, or public financial institutions. Included are all 19 Euro area countries, Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Cayman Islands, Chile, China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Switzerland, Türkiye, United Kingdom, and the United States. Source: Financial Stability Board [FSB] (2022).

Notes: The NBFI sector includes all financial institutions that are not central banks, banks, or public financial institutions. Included are all 19 Euro area countries, Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Cayman Islands, Chile, China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Switzerland, Türkiye, United Kingdom, and the United States. Source: Financial Stability Board [FSB] (2022).

One justification for the lighter touch of NBFI regulation, despite the sector’s prominence, is the view that banks and NBFIs pursue different or parallel intermediation activities. In particular, banks focus on deposits, loans, and payments, while NBFIs focus on capital markets. In this view, then, banks have to be heavily regulated to protect depositors and the real economy, while NBFIs can be lightly regulated and allowed to fail.

This parallel view of NBFIs and banks has influenced financial regulation in the United States for at least 160 years, with banks being heavily regulated but restricted in the scope of their activities. The National Bank Acts of the 1860s prohibited national banks from many businesses, including trust activities, real estate lending, securities underwriting, and credit guarantees (Calomiris, 2020). The Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 renewed the attempt to exclude commercial banks from underwriting securities. And the Volcker Rule, part of the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 (DFA), severely restricts bank participation in certain investment vehicles, and limits proprietary trading at banks to government securities and corporate loans (Richardson and Tuckman, 2017).

However, the parallel view of NBFI and bank activity, along with the regulatory conclusion that NBFIs should be allowed to fail, does not square easily with the de facto official support of NBFIs, most notably during the GFC but more recently as well. Instances include the Federal Reserve’s interventions in the repo markets in 2019 and through the COVID pandemic and shutdowns; the Bank of England’s support of the gilt market in response to the liquidity problems of UK pension funds in 2022; and European governments’ protection of energy producers and derivatives users, also in 2022. The dissonance of the parallel view with the realities of NBFI rescues is reflected in how the Federal Reserve’s 13(3) powers to lend to NBFIs were changed by the DFA, namely, to raise the procedural hurdles to such lending and to prohibit such lending to individual NBFIs, but, in the final analysis, to leave these broad powers in place.

A key challenge to policy based on the parallel view of the NBFI and bank sectors can be expressed in terms of a corollary of Goodhart’s Law (Goodhart, 1975):

As the banking perimeter is used for “control” (regulatory) purposes, but activity around the perimeter can be “manipulated” (via regulatory arbitrage) by banks and NBFIs, the regulatory perimeter inexorably ceases to be useful for control purposes.

Put differently, the NBFI and bank sectors do not exist in parallel, but are actually substitutes in that business lines and intermediation activities flow over time from banks to NBFIs at least in part because of relatively burdensome bank regulation. Furthermore, in this substitution view, NBFIs take on intermediation roles, in kind and volume, that can be systemically important and can lead to rescues by authorities in times of financial stress.

The substitution view of the NBFI and bank sectors, along with the implication that NBFIs can become systemically important, is very much consistent with the powers given by the DFA both i) to the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) to designate NBFIs as systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) and to regulate them accordingly; and ii) to the United States Treasury and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation to resolve a failing large and complex financial company. Metrick and Tarullo (2022) recommend dealing with the substitution problem through a “congruence principle,” through which similar activities are regulated similarly, whether those activities are pursued within NBFIs or banks.

In a recent paper (Acharya, Cetorelli and Tuckman, 2024), we take a different view of the NBFI and bank sectors, arguing that neither the parallel nor substitution views adequately describe how activities align across these sectors. Instead, we posit that intermediation activities—including the types of claims held by each sector, the manner of their financing, and contingent liquidity arrangements—endogenously transform across sectors so as i) to loosen regulatory constraints and reduce regulatory costs across the financial sector as a whole, along the lines of Goodhart’s Law, and ii) to harness the inherent funding and liquidity advantages of bank deposit franchises (Kashyap, Rajan, and Stein, 2002) and access to safety nets (Gatev and Strahan, 2006), whether explicitly in the form of deposit insurance and central bank lender of last resort (LOLR) financing or implicitly in the form of too-big-to-fail insurance. Our transformation view predicts that the intermediation activities and risks of NBFIs and banks become intricately intertwined, which is a result we demonstrate through a variety of cases and empirical analyses of recent developments. That is, banks and NBFIs do not function in parallel or as substitutes, but instead as complements.

To understand our transformation view of the NBFI and bank sectors concretely, consider three categories of transformations that describe relatively recent trends in financial markets:

(i) Loans and Mortgages: Through recent history, banks held corporate and mortgage loans and bore the associated interest rate and default risks. Over time, however, at least in part due to higher capital requirements and tighter regulations on leveraged lending, large volumes of these loans no longer reside on bank balance sheets. Instead, banks have retained indirect loan exposures through senior loans to private credit companies, collateralized loans to mortgage Real Estate Investment Trusts (mortgage REITs, or mREITs), and the generally more senior claims of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized loan obligations (CLOs). Hence, risks of the underlying loans may seem to have left the banking system, but have actually been transformed into more senior holdings of exposures to NBFIs.

(ii) Activities Using Short-Term Funding: Traditionally, banks participated in various businesses that rely on regular or continuing short-term funding. Examples include the following: securitization, in which the purchases of underlying assets are funded until they are securitized and sold as MBS (mortgage-backed securities), collateralized loan obligation (CLOs), or other ABS (asset-backed securities); financing acquisitions in general, and leveraged buyouts (LBOs) in particular, in which acquisitions are funded in anticipation of bond sales to investors; and mortgage servicing, which requires servicers to fund payments of delinquent amounts to MBS investors until government insurance pays the related claims. These activities used to be dominated by banks, but are now dominated by NBFIs. However, banks provide NBFIs with the short-term funding used to carry out these activities in the forms of direct loans, warehouse financing, credit lines, subscription finance loans,1 and bank-sponsored (or credit-enhanced) commercial paper. While perhaps harder to demonstrate empirically, another example would be proprietary trading, which, while forced out of banks and into entities like hedge funds by the Volcker Rule, continues to rely on bank funding through their prime brokerage businesses. In any case, activities using short-term funding are another category of activities that are better described as having transformed across the bank and NBFI sectors than as having shifted from banks to NBFIs.

(iii) Contingent Funding: While the previous category includes the regular or continuing use of short-term funding, which can take the form of credit lines, this third category includes the provision of unusual or emergency short-term funding, or liquidity insurance, which is most often manifested in the drawing down of bank credit lines in unusually high volumes. Activities in this category are those in which NBFIs have replaced banks in financing or other activities but rely themselves on banks for the necessary contingent funding. In other words, the entirety of these activities is not a shift from banks to NBFIs, but a transformation in which regular or continuing financing shifts to NBFIs while unusual or emergency financing remains with banks. The nature of these transformations is easily explained by the inherent funding and liquidity advantages of banks mentioned above. A relatively unheralded example is the post-GFC mandate to clear most derivatives, like interest rate swaps (IRS), that had previously been bilateral and traded over-the-counter (OTC). This mandate has transformed the counterparty risk that banks faced as derivative counterparties of NBFIs to the liquidity risk banks face in providing credit lines to NBFIs to meet calls for additional initial and variation margin. Note that bank credit lines can also provide liquidity insurance for futures contracts, which have always been cleared, but this is not a recent transformation of market arrangements.

While a definitive conclusion would require significantly more research, we believe that the transformations we document are driven at least in part by regulatory arbitrage and consequently could result in an inefficient allocation of activities and risks in the financial system. By “regulatory arbitrage” we mean the process by which finance professionals optimize their businesses subject to pertinent regulations. For example, the management of a bank sets a framework of internal charges for the use of balance sheet, capital, liquidity, etc., and then bankers at that bank seek out profitable transactions given those internal charges. By this mechanism of Goodhart’s Law, resources across the financial system flow to where they are most profitable relative to regulatory costs and constraints. Explicit attempts to circumvent regulations are in this way not necessary.

Opportunities for regulatory arbitrage exist if regulation and supervision do not perfectly internalize the resulting systemic risks or the costs of scarce public resources. We do not attempt to identify the exact components of the current regulatory regime that present regulatory arbitrage opportunities for transforming NBFI and bank businesses as we describe, but we do believe that such opportunities exist. NBFIs are subject to relatively light regulation, particularly with respect to capital and liquidity, and linkages between NBFIs and banks have evolved over time. Furthermore, while parts of bank regulations do treat bank exposures to NBFIs differently from other exposures, safety and soundness regulation of both banks and NBFIs is quite complex and works in combination with other parts of bank regulation, like anti-money-laundering rules, community reinvestment requirements, and operational risk charges. Finally, the academic literature discussed below has established many specific instances of regulatory arbitrage across NBFIs and banks. In short, it is reasonable to question whether the current regulatory regime, created largely in response to the GFC, correctly internalizes the systemics risks of the ever-transforming NBFI-bank landscape.

Accepting the premise that regulatory arbitrage has indeed driven the growth of NBFIs and the transformation of NBFI-bank linkages, the financial system will be characterized by an inefficient allocation of activities and risks. The post-GFC tightening of bank regulation will likely overstate reductions in systemic risk. NBFIs and banks will jointly take more risk than socially optimal, including NBFIs demanding too much extraordinary liquidity from banks under stress. Authorities will consequently have to intervene more often than optimally to preserve the ecosystem of NBFI-bank intermediation, either by direct rescues of NBFIs or by indirect rescues through the banking system.

With respect to policy implications, possible regulatory responses to our transformation view include measuring, monitoring, and accounting for the linkages between banks and NBFIs; attempting to internalize the systemic risk externalities of these linkages; and predetermining the rules governing future decisions to designate NBFIs as SIFIs and subjecting NBFIs receiving emergency support to additional regulatory oversight.

Acharya, Viral V., Cetorelli, N. and B. Tuckman (2024) “Where Do Banks End and NBFIs Begin?” NBER Working Paper #32316.

Calomiris, C. (2020), “The Evolution of Bank Chartering,” Moments in History, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, December 7.

Gatev, E. and P. Strahan (2006), “Banks’ Advantage in Hedging Liquidity Risk: Theory and Evidence from the Commercial Paper Market,” Journal of Finance, Volume 61, Issue2, Pages 867-892.

Goodhart, Charles (1975), “Problems of Monetary Management: The U.K. Experience,” Papers in Monetary Economics, p. 1-20. Vol. 1. Sydney: Reserve Bank of Australia.

Kashyap, A., R. Rajan, and J. Stein (2002), “Banks as Liquidity Providers: An Explanation for the Coexistence of Lending and Deposit‐taking,” Journal of Finance 57(1) 33.73.

Metrick, A. and D. Tarullo (2022), “Congruent Financial Regulation,” in Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, January.

Richardson, M. and B. Tuckman (2017), “The Volcker Rule and Regulations of Scope,” in Regulating Wall Street: Choice Act vs. Dodd Frank, M. Richardson, K. Schoenholtz, B. Tuckman, and L. White, editors, NYU Stern School of Business.

Subscription finance loans are made by banks to private equity funds and are secured by investor commitments to the fund. Using these loans, funds can invest swiftly as opportunities arise without making irregular capital calls on their investors.