This policy brief is based on the paper: Giannetti, M., M. Jasova, M. Loumioti, C. Mendicino (2023): “Glossy Green” Banks: The Disconnect Between Environmental Disclosures and Lending Activities. Working paper https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4424081. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the European Central Bank.

Using confidential information on banks’ portfolios, inaccessible to market participants, we show that banks that emphasize the environment in their disclosures extend a higher volume of credit to brown borrowers, without charging higher interest rates or shortening debt maturity. These results cannot be attributed to the financing of borrowers’ transition towards greener technologies and are robust to controlling for banks’ climate risk discussions. Examining the mechanisms behind the strategic disclosure choices, we highlight that banks are hesitant to sever ties with existing brown borrowers, especially if they exhibit financial underperformance.

Following the Paris Climate Agreement, banks face increasing pressure by regulators and other stakeholders to channel financing towards environmentally friendly firms with a low carbon footprint. In response to these pressures, banks have started to release a wealth of information regarding the sustainability of their lending policies. However, skepticism has grown louder about whether banks strategically disclose information to burnish their sustainability image, while masking their true sustainability impact. That is, their disclosures and claims could just be “cheap talk”.

Banks have incentives to portray themselves as environmentally-conscious in their external reporting. Prior research documents that sustainability-themed disclosures are associated with greater stock liquidity, higher market valuations, lower cost of capital and increased investments from institutional owners (e.g., Plumlee et al., 2015; Barth et al., 2017; Ioannou and Serafeim, 2019; Bonetti et al., 2023; Gibbons, 2023; Krueger et al., 2023). Indeed, recent evidence shows that most sustainability engagement requests that firms receive from institutional investors concern adoption of sustainability reporting (e.g., Kim et al., 2019; Cohen et al., 2023). With regards to other stakeholders, external reporting has been linked to firms’ capabilities in attracting human capital (e.g., deHaan et al., 2023), with employees being particularly attentive to firms’ sustainability actions (e.g., Colonnelli et al., 2024; Krueger et al., 2024). In addition, over time, sell-side analysts have requested from firms to disclose more sustainability-focused information during earnings conference calls (e.g., Sautner et al., 2023a; Sautner et al., 2023b). Collectively, firms’ reporting practices are pivotal to stakeholder perceptions of firms’ sustainability commitments and agenda. Importantly, prior research has provided ample evidence of a link between transparency and greater engagement in sustainability issues (e.g., Bolton et al., 2021; Downar et al., 2021; Fiechter et al., 2022; Tomar, 2023; Cohen et al., 2023; Dai et al., 2024), as transparency reinforces firms’ commitments, but also firms tend to be more transparent when they make commitments. Last, within our research setting, banks have incentives to augment their sustainability-themed disclosures, because real loan portfolio exposures mostly remain opaque to external stakeholders. We thus focus on how banks communicate the sustainability of their lending policies in their annual reports to investors and other stakeholders.

Our sample contains 1,397 reports (annual, sustainability, nonfinancial, integrated) issued by 101 systemic euro area banks over the 2014-2020 period. We develop a dictionary of environment-related keywords based on sustainability topics included in RepRisk—a database that covers ESG risk incidents— and in SASB Materiality Map. The dictionary includes phrases related to energy use and waste management (e.g., “oil”, “renewables”, “natural gas”, “building certificate”, “fracking”, “waste”), emissions (e.g., “carbon”, “CO2”), biodiversity (e.g., “biodiversity”, “forest”, “coral”) and other activities that are considered as damaging for the environment (e.g., “gmo”, “soy”, “sugar”). A detailed list of the keywords is included in Appendix B of the paper. Using content analysis on banks’ reports, we measure environmental disclosures at the bank-year level as the ratio of total environment-related keywords to the total number of words in these reports.

Consistent with the view that banks have strong incentives to augment sustainability-themed disclosures, we show that high environmental reporters have better ESG rating scores and attract a greater volume of green bond underwriting (i.e., firms commonly select these banks to underwrite their ESG-labeled bonds).

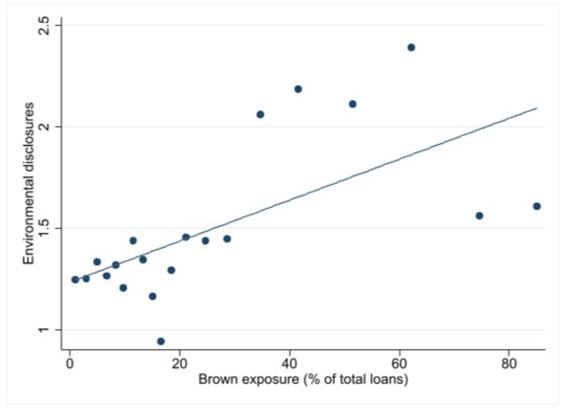

Figure 1

Note: The figure illustrates the relationship between banks’ environmental disclosures and their ex-ante exposure to borrowers in brown industries. It displays a bin scatter plot for the lagged share of the bank’s lending to brown borrowers as a proportion of total credit outstanding (Brown exposure) and the continuous variable of the bank’s environmental exposure. The scatter plots present averages for the data sorted into 20 bins based on exposure to brown firms.

We obtain granular data on sample banks’ loan issuance from Anacredit, a credit repository of the European Central Bank (ECB). We classify borrowers as “green” (i.e., firms whose operations do not adversely impact the environment) and “brown” (i.e., firms with a negative climate footprint) using the emission volume at the borrower’s country-industry-year level. We thus define as green (brown) borrowers whose industry emission levels rank in the bottom (upper) quintile of the variables’ distribution.

As shown in Figure 1, the banks with more extensive environmental disclosures have large exposures to brown industries, which can be potentially indicative of banks’ incentives to communicate about how their lending model is changing towards more green policies. But, do their new loan decisions indeed reflect such a change?

In our empirical analysis, we find that banks that overemphasize the environment in their reports do not lend more to green firms. In fact, these banks are more likely to extend credit to brown firms. This result is robust to defining greenness or brownness using borrower-level annual emissions standardized by total sales (data by Urgentem) or the content in borrowers’ business descriptions. In addition, our findings are not influenced by banks’ climate risk disclosures or forward-looking statements included in the reports.

We also examine whether banks that portray themselves as environmentally conscious are more likely to support brown borrowers in their efforts to transition towards greener business models. We use several proxies to capture whether a firm is in its green transition phase, including borrower’s age, capital expenditures or investments in R&D, or whether the borrower is an Scince Based Target initiative (SBTi) signatory. We fail to find evidence consistent with this argument.

Last, we document that high environmental reporting banks are particularly inclined to continue lending to brown zombie borrowers, i.e., financially underperforming firms with an adverse carbon footprint. This finding is potentially influenced by banks’ incentives to hide their exposure to brown industries by keeping zombie polluters alive. This is because these borrowers will likely default should banks stop channeling loans to them.

Over the past few years, banks have dedicated a substantial portion of their disclosures to amplify their environmental stewardship role. However, do banks “cheap talk”? We address this research question in the context of systemic euro area banks. Using content analysis on banks’ reports and granular detailed data on their lending activities, we show that banks that overemphasize the environment are more likely to lend to brown firms, without being more likely to financially support green borrowers. This result cannot be explained by high environmental reporters lending to brown firms that are in their green transition phase. In addition, we show that these banks continue lending to brown zombie firms, and thus, hide their brown exposures.

Our results have significant policy implications. First, we empirically validate the assessments by the ECB that banks offer inadequate and potentially misleading environmental disclosures (ECB, 2022). Second, the recent adoption of the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) enhanced the investment portfolio transparency of assets managers active in the region. Importantly, the new rules motivated managers to make more environmentally conscious investment choices (Dai et al., 2024). The introduction of similar regulation in the banking sector could potentially yield similar important benefits.

Barth, M., S.F. Cahan, L. Chen, and E.R. Venter. 2019. The economic consequences associated with integrated report quality: Capital market and real effects. Accounting, Organizations and Society 62: 43–64.

Bolton, P., M. Kacperczyk, C. Leuz, G. Ormazabal, S. Reichelstein, and D. Schoenmaker. Mandatory Carbon Disclosures and the Path to Net Zero. Management and Business Review 1 (3), Fall 2021.

Bonetti, P., C.H. Cho, and G. Michelon. 2023. Environmental Disclosure and the Cost of Capital: Evidence from the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster. European Accounting Review, DOI: 10.1080/09638180.2023.2203410.

Cohen, S., I. Kadach, and G. Ormazabal. 2023. Institutional Investors, Climate Disclosure, and Carbon Emissions. Journal of Accounting and Economics 76 (2–3):101640.

Colonnelli, E., T. McQuade, G. Ramos, T. Rauter, and O. Xiong. 2024. Polarizing Corporations: Does Talent Flow to “Good’’ Firms? Working paper.

Dai, J, G. Ormazabal, F. Penalva, and R. A. Raney. 2024. Imposing Sustainability Disclosure on Investors: Does it Lead to Portfolio Decarbonization? Working paper.

deHaan, E., N. Li, and F.S. Zhou. 2023. Financial Reporting and Employee Job Search the rise of disclosure practices that emphasize environmental stewardship. Journal of Accounting Research 61(2): 571–617.

Downar, B., J. Ernstberger, S. Reichelstein, S. Schwenen, and A. Zaklan. 2021. The impact of carbon disclosure mandates on emissions and financial operating performance. Review of Accounting Studies 26: 1137–1175.

European Central Bank, 2022. Supervisory Assessment of Institutions’ Climate-Related and Environmental Risks Disclosures. https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/ecb/pub/pdf/ssm.ECB_Report_on_climate_and_environmental_disclosures_202203~4ae33f2a70.en.pdf.

Fiechter, P., J.M. Hitz, and N. Lehmann. 2022. Real Effects of a Widespread CSR Reporting Mandate: Evidence from the European Union’s CSR Directive. Journal of Accounting Research 60 (4): 1499–1549.

Gibbons, B. 2023. The Financially Material Effects of Mandatory Nonfinancial Disclosure. Journal of Accounting Research, forthcoming.

Ioannou, I., and G. Serafeim. 2019. The Consequences of Mandatory Corporate Sustainability Reporting. Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility: Psychological and Organizational Perspectives, edited by Abagail McWilliams et al. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 452–489.

Kim, I., H. Wan, B. Wang, and T. Yang. 2019. Institutional investors and corporate environmental, social, and governance policies: Evidence from toxics release data. Management Science 65 (10): 4901–4926.

Krueger, P., D. Metzger, and J. Xu. 2024. The Sustainability Wage Gap. Working paper.

Krueger, P., Z. Sautner, D. Y. Tang, and R. Zhong. 2023. The Effects of Mandatory ESG Disclosure around the World. Working paper.

Plumlee, M., D. Brown, R. M. Hayes, and R. S Marshall. 2015. Voluntary Environmental Disclosure Quality and Firm Value: Further Evidence. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 34: 336–361.

Sautner, Z., G. Vilkov, L. Van Lent, and R. Zhang. 2023a. Firm-Level Climate Change Exposure. Journal of Accounting Research 78(3): 1449–1498.

Sautner, Z., G. Vilkov, L. Van Lent, and R. Zhang. 2023b. Climate Value and Values Discovery in Earnings Calls. Working paper.

Tomar, S. 2023. Greenhouse Gas Disclosure and Emissions Benchmarking. Journal of Accounting Research 61(2): 451–492.