References

Dagher, J., Dell’Ariccia, M. G., Laeven, M. L., Ratnovski, M. L., & Tong, M. H. (2016). Benefits and costs of bank capital. International Monetary Fund.

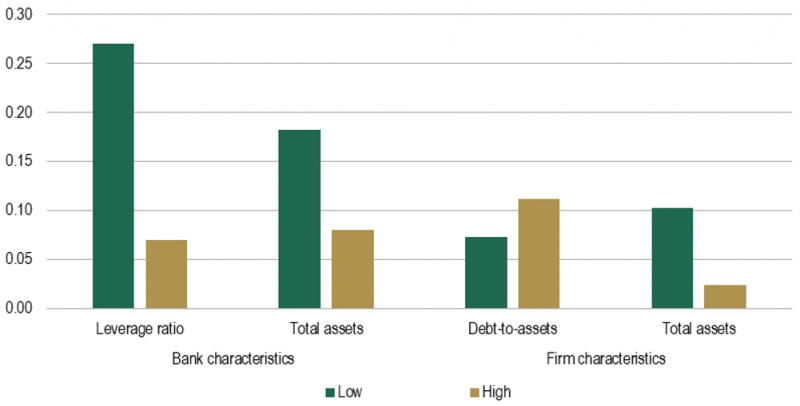

Degryse, H., De Jonghe, O., Jakovljević, S., Mulier, K., & Schepens, G. (2019). Identifying credit supply shocks with bank-firm data: Methods and applications. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 40, 100813.

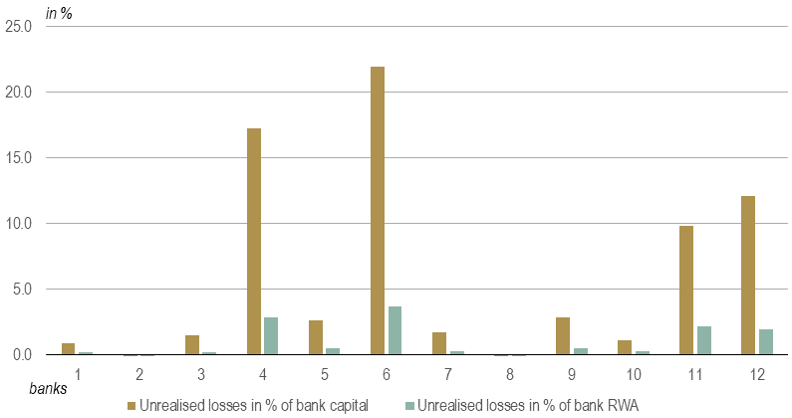

Dursun-de Neef, Ö., Ongena, S., & Schandlbauer, A. (2023). Monetary policy, HTM securities, and uninsured deposit withdrawals. HTM securities, and uninsured deposit withdrawals (April 2, 2023).

Granja, J. (2023). Bank Fragility and Reclassification of Securities into HTM. University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper, (2023-53).

Gropp, R., Mosk, T., Ongena, S., & Wix, C. (2019). Banks response to higher capital requirements: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. The Review of Financial Studies, 32(1), 266-299.

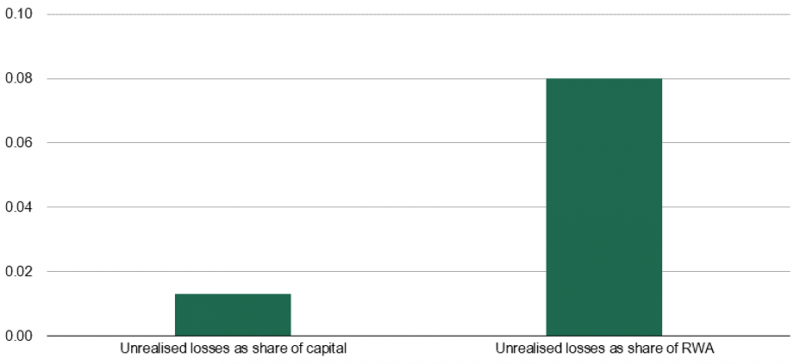

Jiang, E. X., Matvos, G., Piskorski, T., & Seru, A. (2023). Monetary Tightening and US Bank Fragility in 2023: Mark-to-Market Losses and Uninsured Depositor Runs? (No. w31048). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Sivec, V., & Volk, M. (2021). Bank response to policy-related changes in capital requirements. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 80, 868-877.

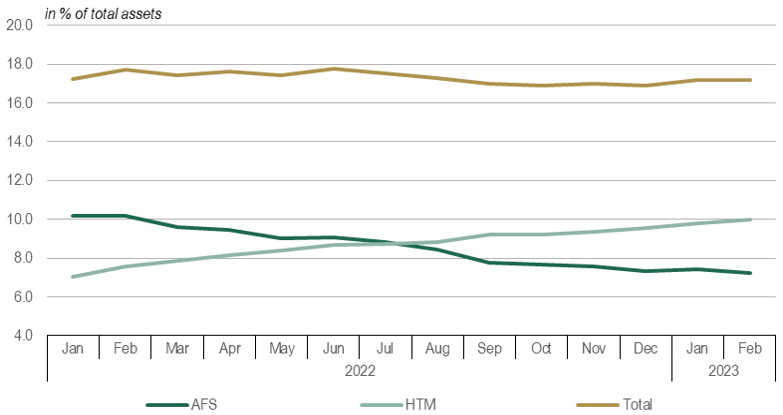

Volk, M. (2023). Is the ECB monetary tightening effective? The role of bank funding and asset structure. SUERF Policy Brief, No 545.