Central banks are increasingly concerned about rising inflation expectations among consumers, but not all consumers are alike: there is a wide spread of different inflation expectations across households. In a recent paper, I show that heterogeneity in the information and subjective models of the economy that underlie these expectations influences how shocks affect the aggregate economy. Applying this to inflation in the UK, I find that features of information and subjective models imply high inflation can become entrenched in household expectations. However, this is only a risk among a certain subset of households, with particular beliefs about the economy.

As inflation rises in many economies around the world, policymakers have become concerned that inflation expectations might become ‘de-anchored’ from inflation targets: “as risks are growing that current high inflation is becoming entrenched in expectations, the urgency for monetary policy to take action to protect price stability has increased in recent weeks” (Schnabel, 2022). Typically, this is seen as a problem because high expected inflation among households may trigger a wage-price spiral, making it harder to bring inflation back under control.

However, while discussions of expectations frequently focus on the average expected inflation across households,1 there is also a great deal of disagreement between households about the likely path of inflation. In February 2022, 31% of households in the Bank of England’s Inflation Attitudes Survey expected inflation below 3% over the next year, while a further 29% expected inflation above 7%.

In Macaulay (2022), I show that this disagreement can influence the transmission of shocks to the macroeconomy, depending on the reasons behind the disagreement. The key to this is that forming an expectation involves taking some information, and passing that through a model to map from the information to the variable being forecasted. A professional forecaster might run recent data releases through a statistical model to forecast inflation; but equally, the same two components are present if a household uses a rule of thumb to take things they observe today, and project them into beliefs about the future. When we see households reporting different inflation expectations from one another, that could therefore be because they have different information, or they could be using different models, or it could be both.2

Disagreement will affect the transmission of macroeconomic shocks if the information and models people use are correlated with each other. Intuitively, a shock will have a larger effect if the people who get the most information about it are also the people whose models say that shock is important for the variables that matter to them – because in that case, the information is concentrated among those who will react most strongly to it. I refer to this as the narrative heterogeneity channel of shock transmission, following the broad definition of narratives in Gibbons and Prusak (2020).

I examine this effect in the UK by using unique features of the Bank of England Inflation Attitudes Survey to measure household information about inflation, and their subjective models of how inflation affects the strength of the economy.

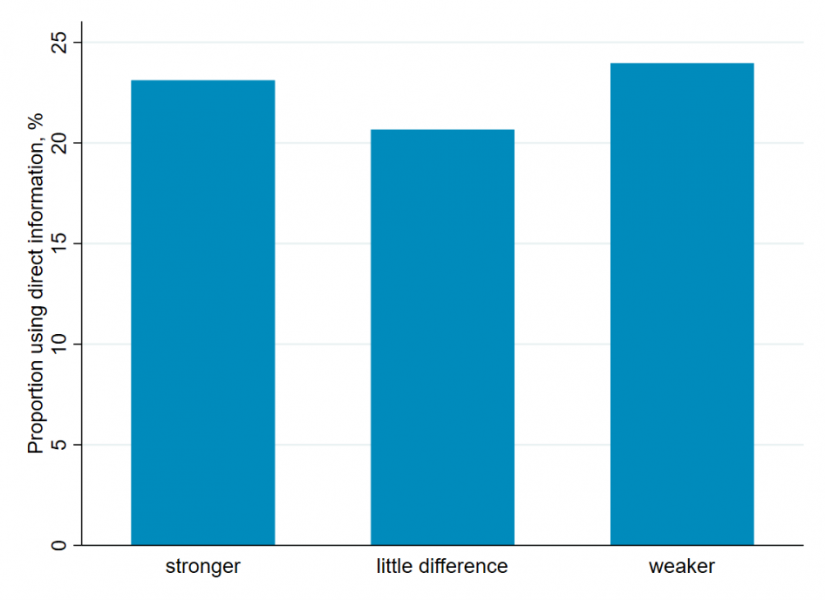

Figure 1 shows the proportions of households who report using direct information about inflation when forming their expectations, split by their beliefs about how higher inflation would affect the strength of the UK economy. Households who believe inflation makes little difference to the UK economy are systematically less likely to make use of information about inflation than either those who believe it has positive or negative effects.3

Figure 1: Proportions of households reporting using direct information about inflation in forming inflation expectations, split by responses to: “If prices started to rise faster than they are now, do you think Britain’s economy would end up stronger, or weaker, or would it make little difference?”

Note: proportions are computed using survey weights provided in the Inflation Attitudes Survey. Source: Bank of England.

This is precisely what would be expected from households making choices about their acquisition of information. For households who believe inflation makes little difference to the economy, there is little perceived value in being well-informed about inflation developments, which explains why they more often choose not to process such information.

Since the majority of households are split between believing inflation makes the economy weaker, and believing it makes little difference, on average information about inflation is concentrated among those with models in which inflation negatively affects the UK economy. This suggests that the narrative heterogeneity channel will cause inflation to have a more negative effect on aggregate demand than if there was no such heterogeneity.

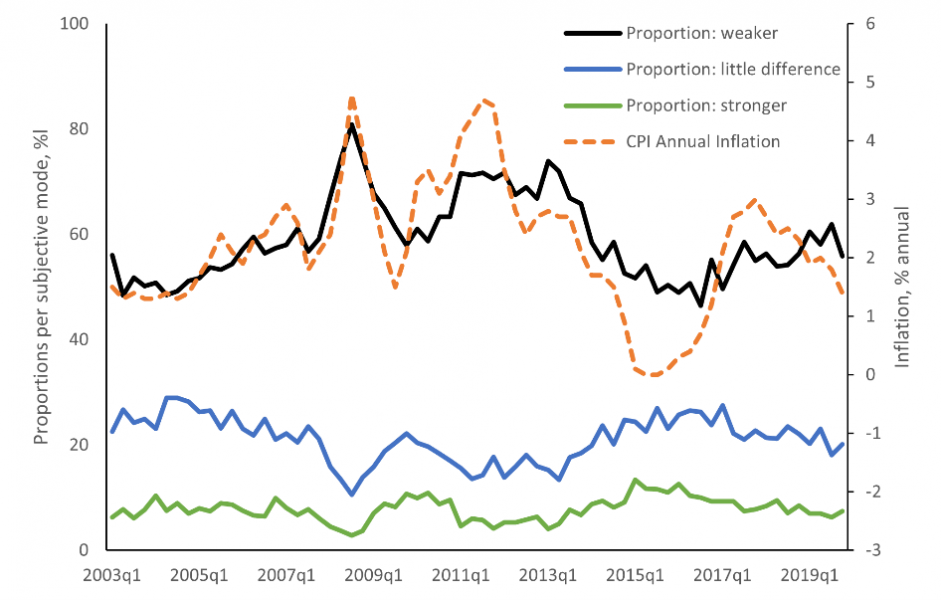

However, this distribution is not static. Figure 2 shows the proportions of households reporting each subjective model over time (left axis), alongside the rate of annual CPI inflation (right axis). Clearly, when inflation has recently been high, more households believe inflation weakens the economy.

Figure 2: Proportions of households giving each response to the question: “If prices started to rise faster than they are now, do you think Britain’s economy would end up stronger, or weaker, or would it make little difference?”

Note: answer “don’t know” omitted from graph. Proportions are computed using survey weights provided in the Inflation Attitudes Survey. Source: Bank of England, ONS.

Indeed, the same pattern is true across households within the same point in time. On average, households who believe inflation weakens the economy perceive that inflation over the last year has been 70 basis points higher than those reporting positive models of inflation interviewed in the same quarter. Information that inflation is currently high is therefore associated with more negative subjective models of inflation’s effects on the economy.

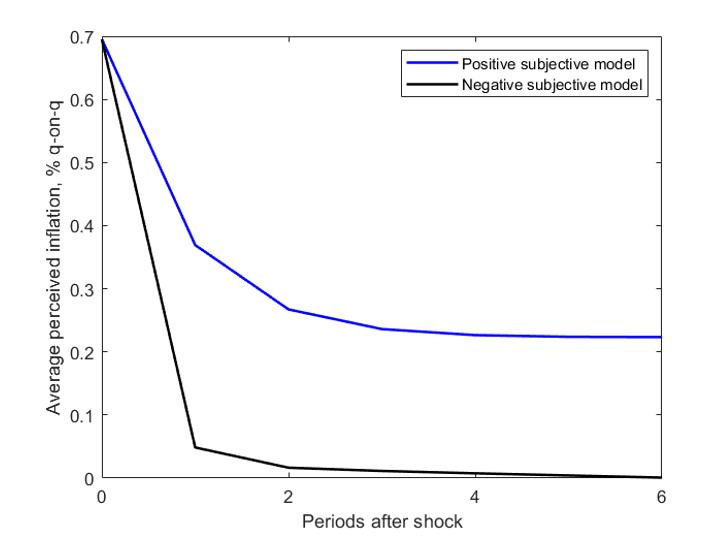

To analyse the consequences of these patterns, I build a model to replicate the results above, then use that to simulate the effects of a one-off spike in inflation. The key features of the model are that households choose how much information to acquire about inflation based on their subjective models (to match Figure 1), and that if a household believes inflation is currently high, they update their subjective models to be more negative about the consequences of inflation (to match Figure 2).

Figure 3 shows the average perceived inflation after the simulated shock, for two groups of households. The black line shows households who initially believe inflation makes the economy weaker. When they observe the information that inflation has gone up, they update those subjective models to be even more negative. But since they now think inflation is even more damaging, information on inflation is even more valuable, so they pay even more attention to that information. When the shock dies away, these households therefore observe that very precisely – so their perceptions of inflation fall quickly back to target.

Figure 3: Simulated average perceived current inflation for two household groups after a one-off inflation shock.

Note: simulations are from the model in Macaulay (2022), calibrated to the UK 2001-2019. Details of the model and simulation can be found in Macaulay (2022). The shock increases inflation by one percentage point in period 0, then inflation returns immediately to target in period 1 and remains there.

The blue line shows households who initially believe inflation makes the economy stronger, for whom the results are very different. As with the negative households, their perceptions rise initially, and that pushes them to be more negative about the consequences of inflation. However, since they started out believing inflation was positive for the economy, this pushes them towards thinking that, on balance, inflation doesn’t matter. They therefore stop acquiring information about inflation. As a consequence, when inflation falls after the shock, they don’t observe it, as they are no longer paying attention to inflation. So they’ll keep on perceiving – and expecting – high inflation, long after the shock has disappeared.

This analysis suggests that policymakers are right to worry about recent high levels of inflation becoming entrenched in expectations. The interaction of the information and subjective models that go into forming expectations means there is a risk of such de-anchoring. However, that risk is concentrated among a certain group of households, who currently believe inflation is good for the economy. They should be the focus of de-anchoring worries, because if their expectations rise too much, they’ll stop paying attention, and it will be extremely hard to bring their expectations back down.

That insight matters for two reasons. First, it tells us whose expectations to track most closely. But second, it implies that if high inflation does become entrenched in the expectations of that group, that will affect the way the economy reacts to shocks going forward. The selective ‘baking in’ of high expected inflation leads a group of previously well-informed people who believed inflation makes the economy stronger to become uninformed. Information therefore becomes even more concentrated among those with negative models of the effects of inflation, meaning that aggregate consumption will react even more negatively to inflation shocks in the future, through the narrative heterogeneity channel.

At the time of writing, however, that cat is not yet out of the bag. In the Inflation Attitudes Survey, average one-year inflation expectations rose by 1.9 percentage points between August 2021 and February 2022. Among the people who say inflation makes the economy stronger, however, expectations rose by less than 1 percentage point.4 It is not too late, therefore, to keep inflation expectations anchored and avoid the consequences analysed above.

Beutel, J. and Weber, M. (2021) “Beliefs and Portfolios: Causal Evidence“, Working Paper.

Gibbons, R. and Prusak, L. (2020) “Knowledge, Stories, and Culture in Organizations”, AEA Papers and Proceedings, 110:187-92.

Macaulay, A. (2022) “Heterogeneous information, subjective model beliefs, and the time-varying transmission of shocks”, CESifo Working Paper, no. 9733.

Macaulay, A. and Moberly, J. (2022) “Heterogeneity in imperfect inflation expectations: theory and evidence from a novel survey”, Department of Economics Discussion Paper Series, University of Oxford.

Schnabel, I. (2022) “The globalisation of inflation”, speech at a conference organised by the O sterreichische Vereinigung fu r Finanzanalyse und Asset Management, 11 May 2022.

For example, Schnabel (2022) cites the median household inflation expectation from the ECB Survey of Consumer Expectations in her discussion.

Recent evidence suggests that there is indeed substantial heterogeneity across households in both of these components of expectations (Beutel and Weber, 2021; Macaulay and Moberly, 2022).

Regressions in Macaulay (2022) confirm this difference remains statistically significant at the 1% level when controlling for time fixed-effects and household characteristics.

These figures are calculated as weighted means of survey responses using the survey weights provided in the Inflation Attitudes Survey.