We study government spending multipliers in a panel of OECD countries. While recent literature has highlighted the differences in government consumption and investment effects, we extend this approach sectorally and report findings that suggest strong heterogeneities across sectors for government spending and output. Differences in price stickiness and sectors’ position in the production network are the main drivers of these heterogeneities.

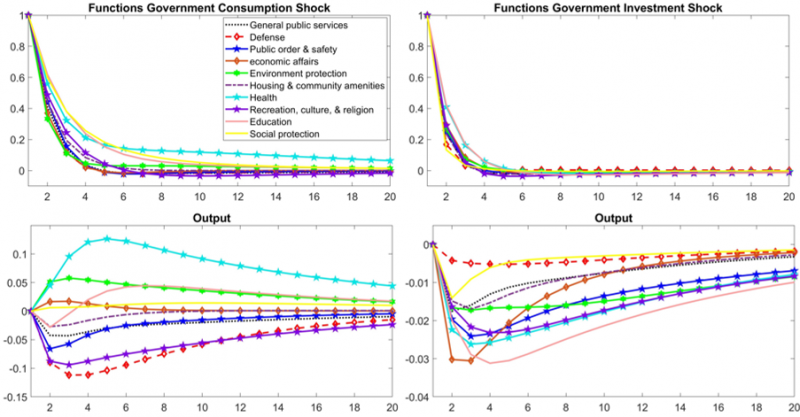

The results from Fig. 3 amplify the heterogeneity of output responses to government consumption and investment shocks. Government consumption spending on functions, such as health and environmental protection6 and education, contributes the most to a positive output multiplier with values of 0.37, 0.31, and 0.14, respectively. Meanwhile, defense, recreation, culture, and religion spending report negative multipliers of −0.69 and −0.54. Moreover, our results show that government investment has a negative multiplier in each reported function.

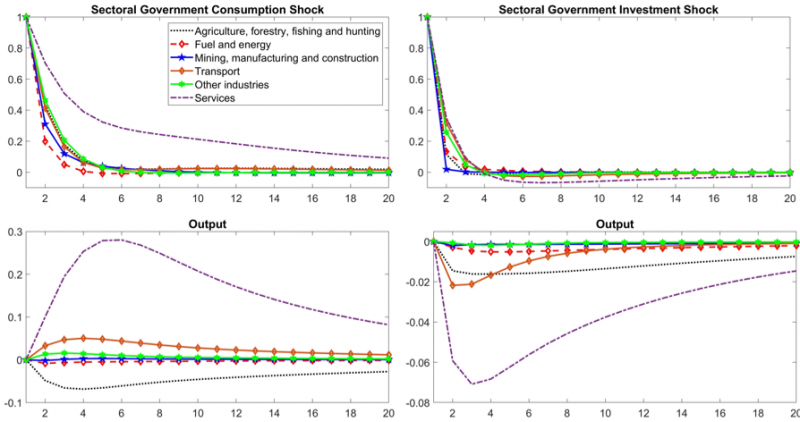

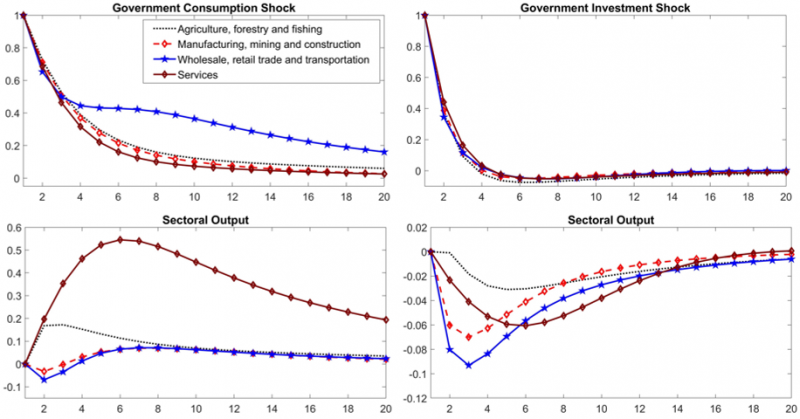

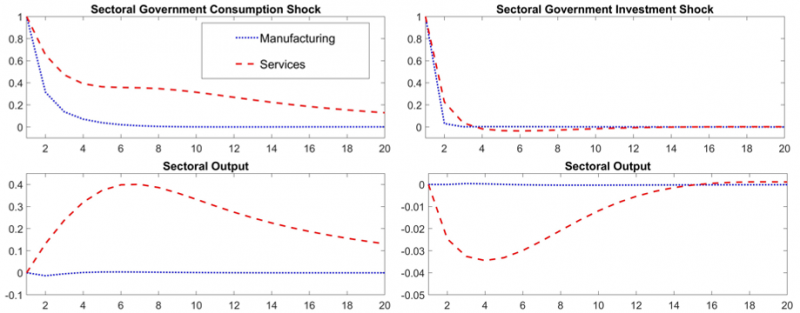

These multipliers are slightly lower than the ones reported for services and manufacturing in Fig. 4, suggesting the possibility of spillovers when looking at the multipliers sectorally to a total government consumption and investment shock. These results are in line with the explanation given by Cox et al. (2020) that reports for the US. The effects of government spending shocks on output are higher in sticky price sectors, such as services, and lower in sectors where firms face more flexible prices, such as manufacturing.9 The results are also in line with Bouakez et al. (2023) since services tend to be more upstream than manufacturing. They do not offer government investment results, which our paper confirms. Our paper contributes to their work by providing evidence for selected OECD countries.

The dataset includes a yearly balanced panel of 18 OECD countries from 1995-2020. We use government spending data at both the sectoral and functional levels. The OECD COFOG and Stats databases provide most of the data, with the exception of sectoral output, which is obtained from the UN database.

Following the important results of Boehm (2020) in distinguishing between government consumption and investment and Ramey (2020) which discusses the macroeconomic consequences of infrastructure investment, in all steps of the analysis we clearly distinguish in our results between government consumption and government spending.

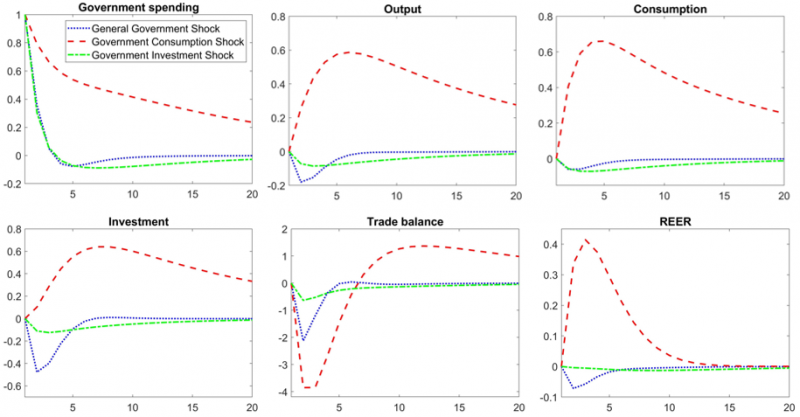

Total government spending multipliers closely track those of government investment spending in line with the work of Antolin-Diaz and Surico (2022), that argue this finding as suggestive evidence that the long-run effects of government spending on output are significantly shaped by public investment.

There are no studies that we are aware of that have looked previously at the impact of government investment on the trade balance and exchange rate highlighting an important contribution of this paper.

The cumulative multiplier shown goes to −0.71.

The literature on the US economy, such as Hasna (2022) and Batini et al. (2022) for the OECD countries, provide evidence that green public investments tend to produce positive output multipliers. Our paper’s results suggest that not considering government consumption spending on what governments define as the environment could lead to bias in public investment green multipliers. Another explanation could be due to different definitions of what constitutes green and non-green used by the other authors.

These results are fairly in line with some of the multipliers reported by Gabriel et al. (2023) on the Eurozone area using sectoral regional data. Nevertheless, they do not distinguish between government investment and government consumption. They report −0.14 for Agriculture after 4 years of impact, 0.69 for services, 0.27 for construction, and 0.66 for the industry.

The evidence presented in Bils and Klenow (2004), Klenow and Kryvtsov (2008) and Nakamura and Steinsson (2008) suggest that manufacturing can be considered a sector where firms face flexible prices while firms in the services sector adjust prices less frequently.

They argue that ‘‘when the government demands more goods from all the industries, sectors located upstream raise their production to meet not only the higher demand from the government, but also the additional demand for intermediate goods from their customer industries. The value added of upstream sectors therefore rises more than that of downstream sectors, ceteris paribus’’.