This article represents the authors‘ personal opinions and does not necessarily reflect the views of the Deutsche Bundesbank or the Eurosystem.

Wealth in addition to income determines to a large degree an individual’s consumption opportunities and economic situation, which should in turn affect their subjective well-being. We analyse empirically the relationship between life satisfaction as an indicator of subjective well-being and households’ wealth. Using micro-data from the German wealth survey (Panel on Household Finances – PHF), we find that (i) individuals’ life satisfaction is statistically significant and positively associated with their households’ wealth holdings, (ii) different components of wealth, as well as debt, have differential effects on life satisfaction, (iii) both wealth levels and wealth holdings relative to other households matter for life satisfaction.

Whether money can buy happiness is a question addressed by several authors in the empirical literature on subjective well-being (see e.g. Kahneman and Deaton 2010). A common finding of most of these studies is that an individual’s financial situation has a positive impact on their subjective well-being (SWB). Classic micro-economic theory can be used to explain this finding: an individual derives utility from consuming goods, which can be purchased using current income, saved or accumulated income (gross wealth), or new debt. Thus, higher levels of income and wealth should – through increased consumption opportunities – lead to higher utility levels. Apart from providing consumption opportunities, wealth has some additional features making it prone to positively influencing SWB: it can be used to smooth consumption over an individual’s life cycle, it provides security against income shocks, it serves as collateral for debt, and it generates income itself. Given these functions of wealth it is not surprising that several recent studies have found a positive relationship between SWB and wealth holdings (for example Hagerty and Veenhoven 2003; Headey and Wooden 2004; Brown and Gray 2016; Office for National Statistics 2015; Foye et al. 2018).

Most existing studies, however, have focused on only one aspect of an individual’s financial situation, i.e. income (Weinzierl, 2005). Relying exclusively on income and ignoring wealth may lead to wrong conclusions regarding the relationship between SWB and an individual’s financial situation (Clark et al., 2008). Moreover, most of the studies, which do include wealth, were limited either to one measure of total net wealth or to a single wealth component such as homeownership or savings (see Jantsch and Veenhoven (2019) for a comprehensive review). Going beyond the classic absolute utility theory that focuses on the levels of income, wealth or consumption, the levels of these measures relative to others also seem to affect SWB (Kuhn et al, 2011; Pollak, 1976).

In our paper Jantsch, Le Blanc, Schmidt (2022), we investigate two important aspects of the link between SWB and wealth: first, we consider wealth and its different components such as real assets, financial assets, secured and unsecured debt, and investigate how these are associated with our measure of SWB, i.e. life satisfaction. Furthermore, we discuss whether the consideration of wealth alters the relationship between SWB and income. Second, we investigate the importance of one’s own wealth relative to the wealth of other households for life satisfaction. Specifically, we analyze whether and how the wealth of an individual’s peer group matters.

We find that (i) individuals’ life satisfaction is statistically significant and positively associated with their households’ wealth holdings, (ii) different components of wealth, as well as debt, have divergent effects on life satisfaction, (iii) both wealth levels and wealth holdings relative to other households matter for life satisfaction.

For our analysis, we use panel micro-data for over 2,000 households from the German Wealth Survey, the Panel on Household Finances, PHF, for 2010 and 2014 (see Altmann et al. 2020 for details). The PHF is one of the few surveys available in Germany that is dedicated to measuring wealth at a very detailed level. It contains a self-reported measure of life satisfaction as an indicator of SWB and has a substantial panel component.

The key question for our analysis is “In general, how satisfied are you currently with your life as a whole?” which respondents answer by ticking one option on a list running from 0 “completely dissatisfied with life” to 10 “completely satisfied with life”.

Simple descriptive analysis shows that the average life satisfaction level is identical in 2010 and 2014, at 7.3. However, while the overall distribution of life satisfaction was very stable across time, there were many transitions at the individual level. About 34% of the respondents in our sample reported a reduction in life satisfaction, 34% an increase, and 32% no change.

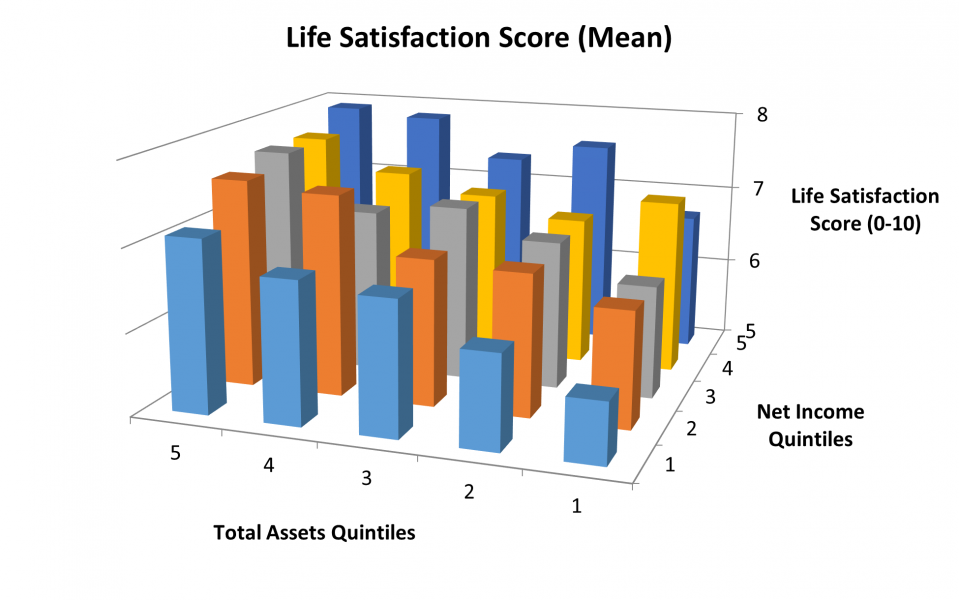

The main interest of our analysis is not how life satisfaction as such changed, but how it varies/changes with wealth and its components. Figure 1 shows the joint distribution of income, wealth and median life satisfaction for the pooled sample. Life satisfaction is lowest for respondents in the lowest quintile of income and wealth. As soon as income is higher, life satisfaction increases regardless of the position in the wealth distribution of the household. Life satisfaction also increases with wealth, but for low levels of income, wealth needs to be at least in the third quintile for an increase of life satisfaction.

Figure 1: Average Life Satisfaction by Net Income and Total Assets

Source/Notes: PHF 2010/11 and PHF 2014 pooled – SUF Files, unweighted, panel households only.

In our paper (Jantsch, Le Blanc, Schmidt, 2022), we conduct more detailed analysis on the effect of the level of wealth and debt on individual’s life satisfaction and find:

In order to account for the fact that an individual’s life satisfaction might be affected by income or wealth in relative rather than in absolute terms, we first need to define the respective reference group of each individual under consideration. We follow Ferrer-i-Carbonell (2005) and calculate reference income, reference wealth, and reference debt of people belonging to the same education level (primary and lower secondary education, upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education, and first and second stage tertiary education), the same age group (

By exploring how the relevant reference group’s wealth is associated with one’s life satisfaction, we find:

Most existing studies look at the link between subjective well-being and income and have neglected wealth and its components, not least because of a lack of suitable data on individuals’ and households’ wealth. The encouraging outcome from our research is that the association between life satisfaction and income is robust to including wealth in the analysis. Our results indicate that wealth is important for life satisfaction; if it was not taken into account, an important explanatory factor for life satisfaction might be neglected. However, our analysis does not allow conclusions to be drawn about the relative importance of income and wealth. The characteristics of income and wealth seem to be too different to compare. Not least because income is a flow and wealth a stock.

Our analysis also shows that the associations between life satisfaction and individual asset components differ. We suppose that it is due to the fact that the different components of total assets have differing characteristics, such as varying degrees of liquidity. In addition, real assets are more visible to others than financial assets, which in turn could affect the evaluation of life satisfaction through status effects. Characteristics of various debt components differ too. We also show that the effects of wealth and debt are more pronounced in poorer regions. We attribute this finding, at least partially, to comparison effects under the assumption that individuals are affected by other individuals in their region. Our results regarding reference wealth support the notion that comparisons with other individuals matter for an individual’s life satisfaction.

Altmann, K., R. Bernard, J. Le Blanc, E. Gabor-Toth, M. Hebbat, L. Kothmayr et al. (2020). ‘The Panel on Household Finances (PHF) – Microdata on household wealth in Germany’, German Economic Review vol. 21(3), pp. 373–400.

Brown, S. and D. Gray (2016). ‘Household finances and well-being in Australia: An empirical analysis of comparison effects’, Journal of Economic Psychology vol. 53, pp. 17–36.

Clark, A.E., P. Frijters and M.A. Shields (2008). ‘Relative Income, Happiness, and Utility: An Explanation for the Easterlin Paradox and Other Puzzles’, Journal of Economic Literature vol. 46(1), pp. 95–144.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2005). ‘Income and Well-Being: An Empirical Analysis of the Comparison Income Effect’, Journal of Public Economics vol. 89(5-6), pp. 997–1019.

Foye, C., Clapham, D., and T. Gabrieli (2018). ‘Home-ownership as a social norm and positional good. Subjective wellbeing evidence from panel data’, Urban Studies 55(6), pp. 1290–1312.

Hagerty, M.R. and R. Veenhoven (2003). ‘Wealth and happiness revisited–growing national income does go with greater happiness’, Social Indicators Research vol. 64(1), pp. 1–27.

Headey, B. and M. Wooden (2004). ‘The Effects of Wealth and Income on Subjective Well-Being and Ill-Being’, Economic Record vol. 80(Special Issue), pp. S24-S33.

Jantsch, A. and R. Veenhoven (2019). ‘Private Wealth and Happiness: A Research Synthesis Using an Online Findings-Archive’, in (G. Brulé and C. Suter, eds.), Wealth(s) and subjective well-being, pp. 17–50, Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Jantsch, A., J. Le Blanc and T. Schmidt (2022). ‘Wealth and subjective well-being in Germany, Deutsche Bundesbank Discussion Paper 11/2022, Frankfurt am Main.

Kahneman, D. and A. Deaton (2010). ‘High Income Improves Evaluation of Life Nut Not Emotional Well-Being’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America vol. 107(38), pp. 16489–16493.

Kuhn, P, Kooreman, P., Soetevent, A. and A. Kapteyn (2011). ‘The effects of lottery prizes on winners and their neighbors: Evidence from the Dutch postcode lottery’, American Economic Review 101(5), 2226–2247.

Office for National Statistics (2015). ‘Relationship between Wealth, Income and Personal Well-being, July 2011 to June 2012’, Wealth in Great Britain Wave 3 – Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk) (last accessed: 16 August 2016).

Pollak, R. (1976). ‘Interdependent Preferences‘, American Economic Review 66(3), 309–320.

Weinzierl, M. (2005). ‘Estimating a relative utility function’.