Disclaimer1

Behind the recent hawkish pivot by DM central banks stands a recognition that inflation will likely remain elevated as we move through 2022. However, central banks continue to guide that policy stances can be normalized gradually, relying on the inflation process of the past quarter century. Central bankers continue to see price and wage inflation anchored by their medium-term commitment to stabilize inflation close to 2%. This is complemented by their view that secular disinflationary forces linked to the global mobility of goods and labor remain in place.

The initial move higher in inflation last year reflected concentrated pressures in a narrow set of items where supply constraints pushed up prices. As such, the spike did not challenge views on the process determining inflation. However, recent developments show inflation pressures broadening across sectors and countries and hint that a reflationary feedback loop is taking hold between strong growth, building cost pressures, and private sector behavior. Labor markets are tightening rapidly with unemployment rates dropping to levels consistent with estimates of “full employment” across the DM and in many EM economies.

While central banks still trust in the inflation process of the last three decades, recent performance is hard to explain within the framework of standard inflation modeling. At a minimum this should serve as a reminder of our limited ability to anticipate large shifts in inflation performance. Indeed, it took time for both forecasters and markets to recognize the past two significant global inflation regime shifts – upward during the 1960-70s and downward during the 1980-90s. Both episodes also prompted a fundamental reassessment of inflation modeling.

It is against this backdrop that current events should be seen: As a challenge to the prevailing view by central banks and market pricing that the inflation process will produce a return to the low and stable inflation environment of the past quarter century. While recognizing that there is considerable uncertainty in distinguishing signal from noise in current inflation readings, we believe three pillars of standard inflation models are vulnerable to be toppled in the face of the shocks unleashed by the pandemic and its recovery.

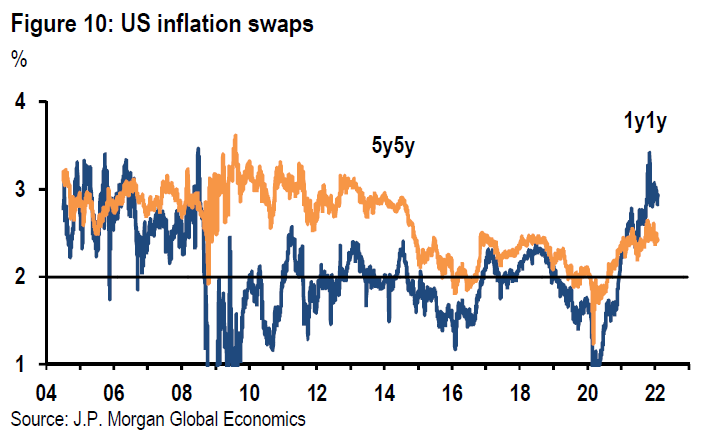

• Shocks may be persistent if core inflation breaches a threshold. Empirical research shows little persistence of inflation shocks, but this hypothesis has not been tested in the face of a large shock. As noted in a recent FRB paper questioning whether inflation expectations play an important role in the inflation process, the likely breaching of inflation thresholds over 2021-22 could change the role past inflation performance plays in future price- and wage-setting behavior. Although medium-term market expectations of inflation have remained anchored, core inflation looks likely to break out of its narrow range in the US and Europe for two full years (Figure 1). Regardless of the source of this move, there is a strong case to be made that decisions on price- and wage-setting will be influenced by a sustained core inflation breakout even if central banks’ medium-term objectives remain credible.

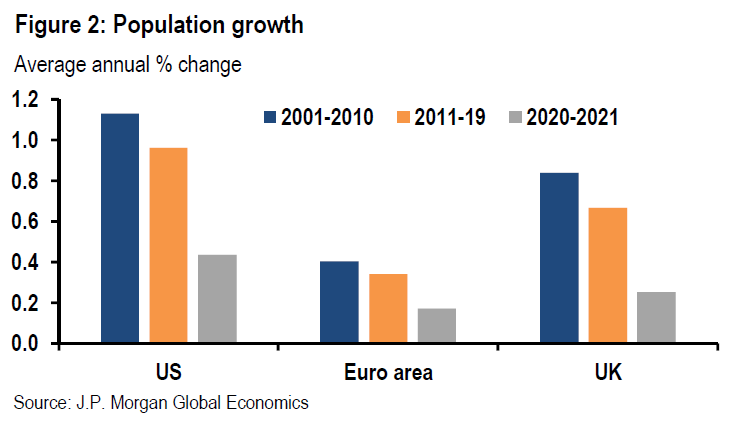

• We’re not in Guangzhou anymore. Although pandemic-related supply constraints should abate, there are good reasons to see a lasting imprint of the pandemic on the mobility of goods and labor globally. Shocks related to the pandemic and the 2018-19 US-China trade war have exposed vulnerabilities of supply chains and an underlying shift is likely taking hold in which a focus on lowering costs is balanced by the need for reliable sources that serve regional demand hubs. In addition, immigration has been a significant source of potential growth for DM economies and has worked as a cyclical cushion aligning labor supply with economic demand (Figure 2). The lingering effects of the pandemic, combined with a shift in US immigration policy and the UK exit from the EU, are likely to produce lasting impediments to the free flow of labor.

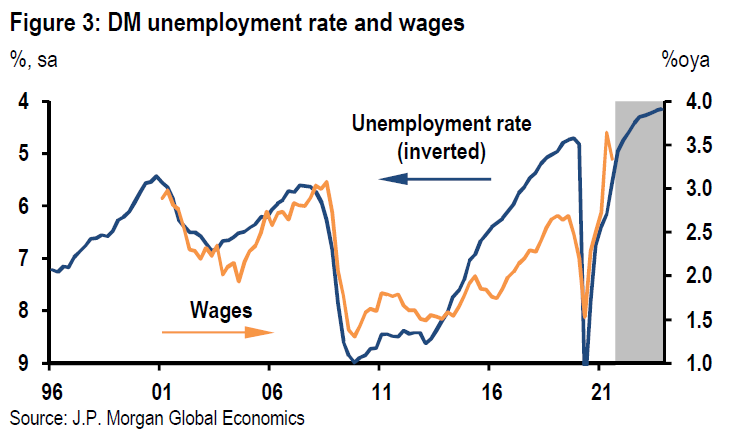

• Extreme labor tightness should steepen wage Phillips curve. At the same time that inflation breaches thresholds of the last three decades, DM unemployment rates are poised to approach 50-year lows this year (Figure 3). Although wage inflation has displayed less sensitivity to labor market conditions over the past decade, the move towards historically tight labor markets could prompt a more significant resurgence in labor bargaining power.

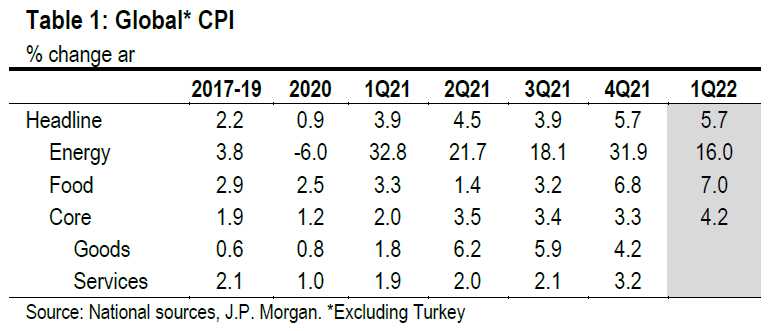

As inflation has moved higher over the past year it has been difficult to identify its underlying trend. Indeed, the jump in CPI inflation to a 4.2%ar during the middle quarters of 2021 largely was attributable to core goods and energy price pressures – components affected by supply constraints and that account for only about one-third of the CPI price basket.

However, in recent months price pressures have broadened dramatically. Over the last two quarters, food and services prices have accelerated sharply, both posting average gains more than twice their pre-crisis paths (Table 1).

We had anticipated pandemic recovery dynamics to extend beyond the narrow set of items directly linked to supply bottlenecks as rising input prices and slower delivery times generate broad-based pressures. In addition, we expected a normalization of service price inflation from levels depressed by 2020 lockdowns. But the intensity of the acceleration in the broader CPI basket in recent months has been surprising. Here a number of developments are worth noting.

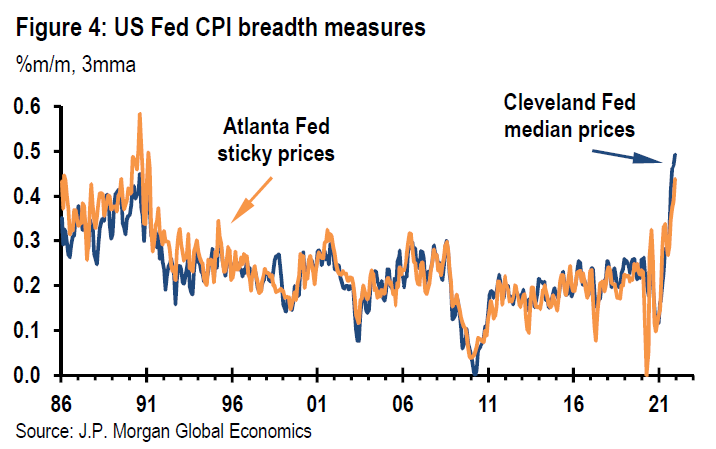

• US measures of CPI breadth have moved up substantially. The Cleveland Fed median CPI and the Atlanta Fed sticky price index have each increased at a 0.5%m/m average pace in the last three months, both posting their fastest increases in three decades (Figure 4).

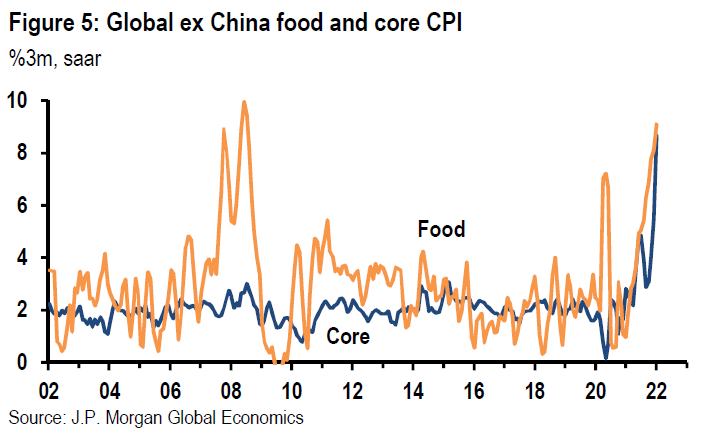

• Food inflation is now approaching its fastest pace of the last quarter century (Figure 5). Food prices tend to move higher when core inflation accelerates but during surges in 2008 and 2010-11, food inflation aligned with commodity price pressures, which affected core inflation to a lesser extent. However, this time appears to be different as food price inflation is far outpacing the pressures evident in agricultural commodity prices.

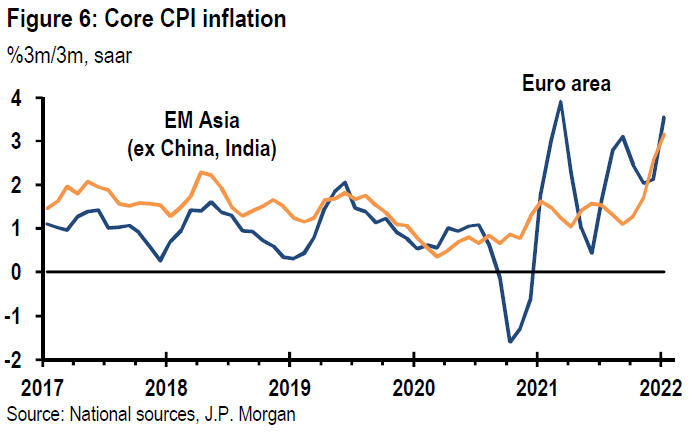

• Through last summer, the acceleration in global inflation was heavily concentrated in the US and high-yield EM economies. However, in recent months inflation pressures have broadened globally with notable accelerations in the Euro area and EM Asia (Figure 6). Among large economies only China and Japan stand out with CPI increases in line with pre-pandemic norms.

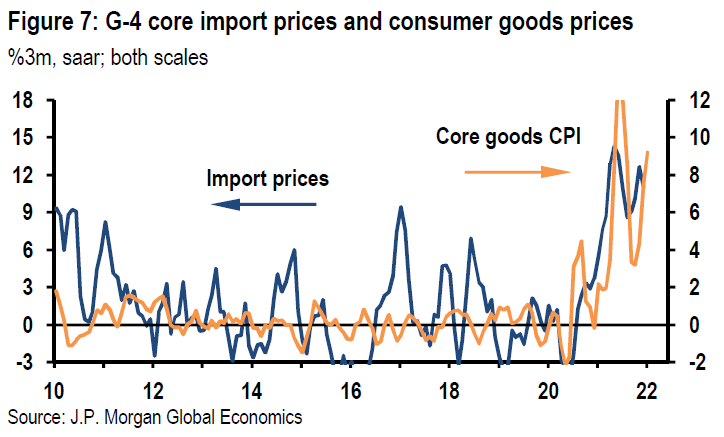

• The acceleration of food and services price inflation is not the only surprise in recent inflation news as core goods price pressures have intensified after showing signs of cooling in 3Q21. For the G-4 economies, both the core goods CPI and non-fuel import prices have increased at a roughly 10%ar in the last three months, highlighting the persistence of intense global pressure on goods prices (Figure 7).

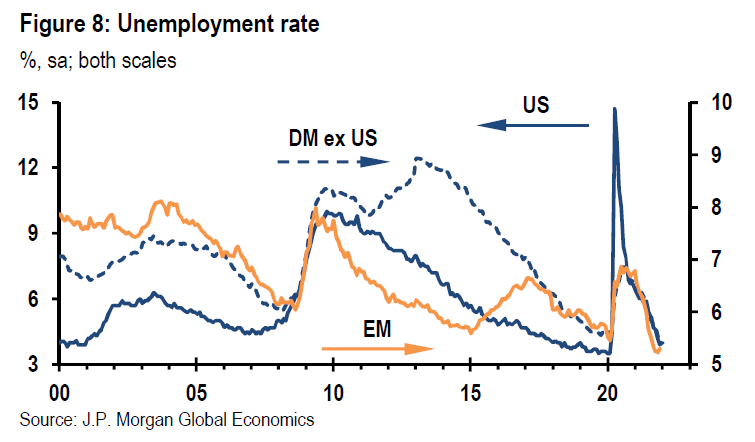

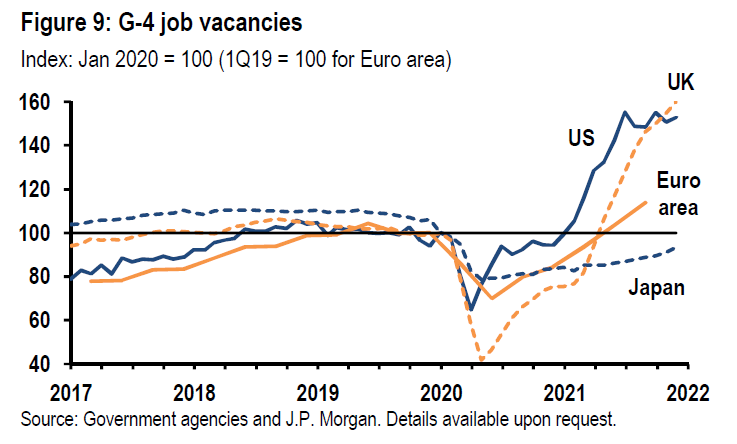

News that inflation pressures are broadening has been accompanied by a rapid tightening in global labor markets. Unemployment rates now stand at or below pre-pandemic levels across most of the globe, an outcome at odds with the still-substantial shortfall of global GDP from its pre-pandemic path (Figure 8). A number of pandemic-related factors contribute to this disconnect: labor force participation has been depressed (US and EM); policies preserved jobs while reducing the workweek (Europe); and a concentrated hit to EM informal sectors likely reduced GDP while not being fully reflected in measured employment.

We expect these drags to fade as the post-pandemic normalization continues but also anticipate that above-potential growth and the likely rotation of growth toward labor-intensive services will promote further labor market tightening.

Labor markets dislocations have certainly contributed to supply pressures that have pushed inflation higher across the globe (Figure 9). However, labor cost pressures are not yet broad-based and the overall acceleration of DM wage inflation over the past year has been far too modest to be a key driver of the recent inflation surge.

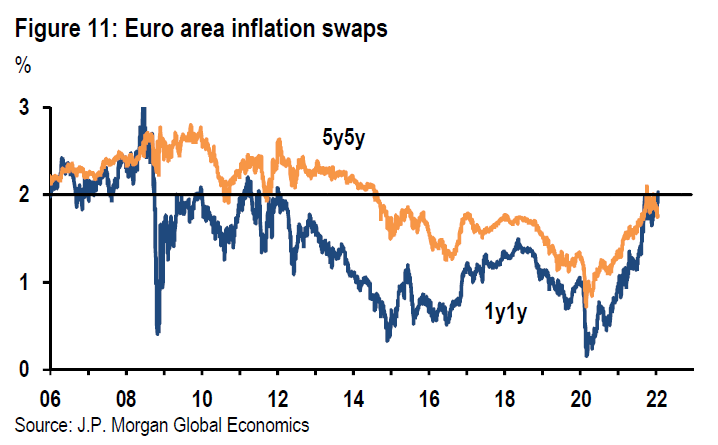

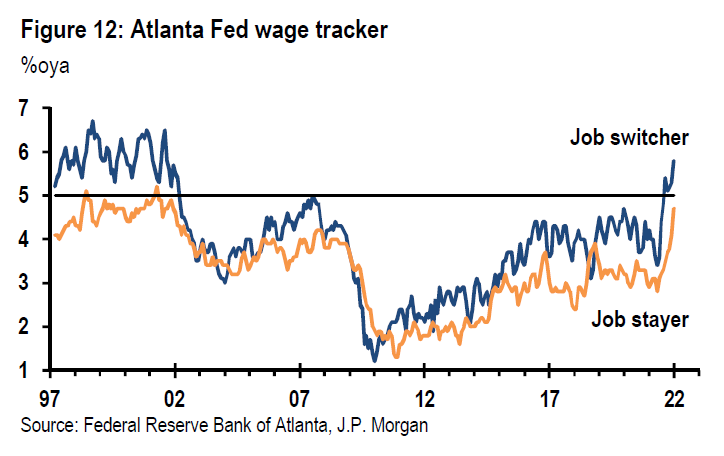

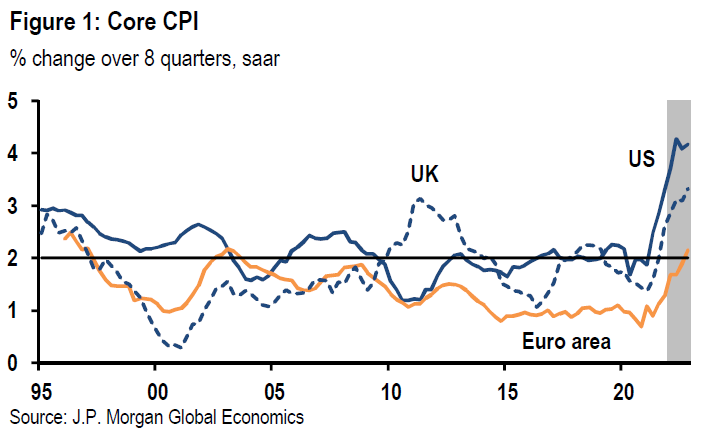

While the latest inflation news raises concerns that the inflation process is shifting, it is far too early to conclude that it has shifted. Looking beyond inflation, two other signals hinting at an underlying change are worth highlighting. The first is the substantial rise in one-year-ahead one-year inflation swaps relative to more medium-term measures of inflation expectations in recent months (Figures 10 and 11). A similar break in the opposite direction occurred after the global financial crisis and was a leading indicator of a broad disinflationary shift. Second, a steepening in the wage Phillips curve is consistent with the shift upward in the Atlanta Fed measure of job switcher wage inflation (relative to job stayers), which is current sitting close to 6%oya (Figure 12).