This article was authored by Richard Portes (London Business School and ESRB Advisory Scientific Committee) and Steffen Kern (Chief Economist, ESMA), both Co-Chairs of the ESRB Non-Bank Expert Group and the ESRB Crypto-Asset Task Force, and by Antoine Bouveret (ESMA), and Dorota Okseniuk (ESRB Secretariat). The article reflects the views of the authors, which may not reflect the positions of the organisations with which they are affiliated.

Abstract

Non-bank financial intermediation is playing a growing role in providing credit to the real economy and the financial sector, and 2023 saw the market return to its growth trajectory. Market-based sources of financing are urgently needed in Europe, but this trend can bring risks to financial stability especially when non-bank entities use leverage, are exposed to liquidity mismatches or are highly interconnected with the rest of the financial system. This paper reviews structural features and risks to the EU financial system, such as the international dimension of the money market fund sector, as well as recent developments related to private finance and crypto assets. As current discussions on the Savings and Investments Union and the macroprudential approach for non-banks progress, a system-level view of non-bank finance in the EU points to the potential but also to the diversity and complexity of the markets and institutions.

Non-bank finance will be high on the EU agenda as the Parliament and the Commission start their new term.

Brussels is taking a fresh look at how to boost Europe’s capital markets, an objective given high priority by the April 2024 European Council. Market-based finance in Europe is widely considered to fall far short of its potential in terms of efficiency and its contribution to economic growth.

In parallel, the EU Commission has launched a review of the Union’s macroprudential policies1 and the framework for non-bank financial institutions2 in particular. Important questions are on the table about how non-bank finance in Europe can be made even more resilient and crisis-proof and how supervisory authorities can be better equipped for their work.

Both projects, the Savings and Investments Union and the Macroprudential Review, are closely interrelated: Since financial stability is a prerequisite for sustainable development of the financial system, macroprudential policies should be designed to support the plan for better capital markets. And as capital markets grow, so do financial risks, and the macroprudential framework must be fit to address them.

But how are EU non-bank financial markets and institutions doing currently? And in which areas are the risks rising3? The European Systemic Risk Board’s EU Non-bank Financial Intermediation Risk Monitor assesses the questions on an annual basis, and the 20244 edition highlights the growth dynamics and key areas of risks.

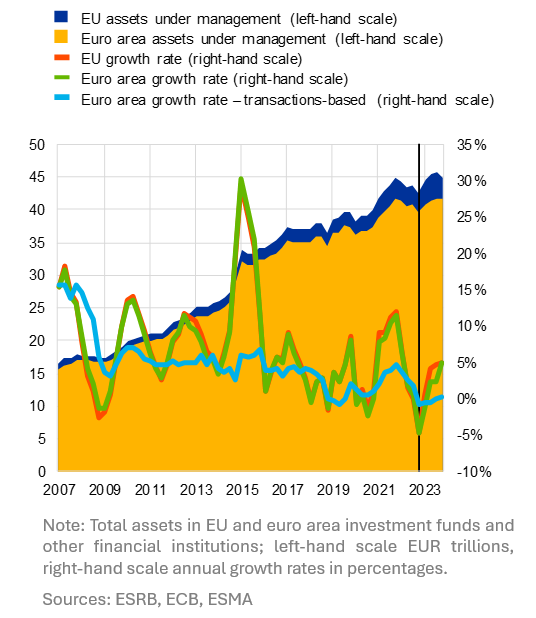

After contracting in the previous year, 2023 saw the return of non-bank financial activities to their long-running growth trajectory. The size of the market increased in the first half of 2023, mainly reflecting positive valuation effects. Total assets of EU investment funds and other financial intermediaries (OFIs) increased to €44.8 trillion at the end of 2023 compared with €42.7 trillion at the end of 2022, reaching again their end-2021 level. Overall, assets of investment funds and OFIs accounted for 41% of European financial sector assets at the end of 2023.

Investment funds and OFIs remained an important source of funding to the EU corporate sector. Financing obtained through debt securities issuance grew markedly in 2023, to €36 billion from €19 billion the year before. Credit through debt securities rebounded to 21% of total credit to corporates. Credit provided by funds and OFIs in the form of loans or debt securities also increased to 21%.5 Both market-based and non-bank credit have roughly doubled since the Global Financial Crisis.

Figure 1. The size of the monitoring universe expanded in 2023

As non-bank activity regains growth momentum, risks have remained high and are rising in some areas.

Cyclically, the rapid transition from low interest rates and muted growth prospects at the current juncture are testing the resilience of markets, just as they test the resilience of banks. Investment funds and OFIs have so far managed the transition to higher rates, but the effect of tighter financing conditions has not yet fully materialised. Downside valuation risks remain high with stretched valuations in some market segments. The outlook for the commercial real estate market is particularly challenging, and political uncertainty is a growing source of risk.

Structurally, risks can be amplified by vulnerabilities of non-bank financial intermediaries. Liquidity mismatch, use of leverage, and interconnectedness can contribute to systemic risk, amplifying and spreading shocks throughout the financial system. These vulnerabilities apply not only to investment funds and other intermediaries, but also to crypto-assets and their associated intermediaries.

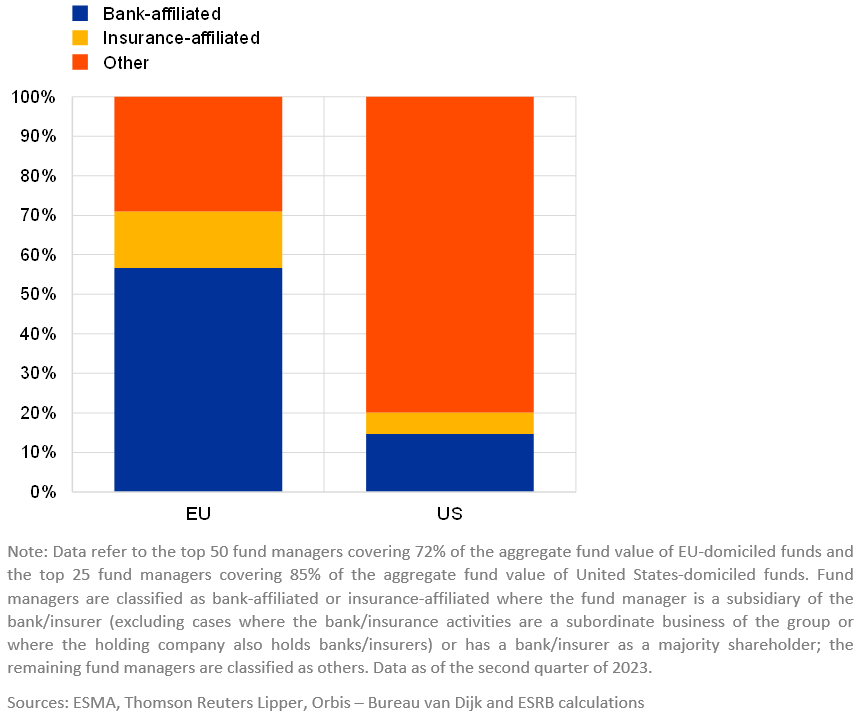

Linkages among financial institutions can facilitate provision of credit to the real economy and risk sharing. But those interconnections, together with illiquidity and leverage, can also be a core weakness in non-bank finance and can transmit or amplify shocks through the system. One such connection is bank ownership of asset management companies. This link is particularly strong in the EU, where close to 60% of fund assets are managed by companies owned by banks. Contrast this with the US, where 80% of asset managers are free-standing.

Figure 2. Affiliation of largest asset managers in the EU and the US

In times of stress, these dependencies can incentivise owning banks to step-in and support affiliated funds. And vice-versa – financial stress for banks can impact their affiliated funds. Evidence of this effect comes from large outflows from funds affiliated with Credit Suisse when the bank went downhill in March 2023. And even beyond turmoil, such affiliations can affect the behaviour of funds and influence their portfolio decisions and their investor base, as our analysis suggests. Insurance companies tend to invest more in insurance-affiliated funds compared with independent or bank-affiliated ones. At the same time, funds with bank-affiliated managers display the highest share of households as investors, which could reflect banks’ well-established distribution networks.

Private finance has more than tripled in the last ten years, not just globally, but also in the EU. European assets under management were estimated at €2.4 trillion and represented around 23% of the global total as of 2022. The growth can be attributed to favourable regulatory frameworks, sustained institutional demand, and search for yield. Key players are private equity and private loan funds authorised as EU Alternative Investment Funds, with exposures in mainly unlisted equity, real estate, and direct loans.

Private finance plays an important role in the economy by providing alternative or complementary financing to companies or investment projects with high financing needs that might not meet the criteria or “risk appetite” for financing from other sources. But it could also contribute to over-indebtedness and financial imbalances. As this financing channel expands, it is important to understand and monitor the specific risks that come with the individual business models.

The risks that the ESRB will have on its watchlist going forward include high credit risk and leverage across complex layers of exposure; bespoke valuation practices and the associated valuation risks; procyclicality from leverage pressures; and macroprudential policy leakage, as potentially weaker borrowers and loan structures prevail in private finance transactions, including lower underwriting standards, weaker covenants and aggressive repayment assumptions. Interlinkages in the private finance space should also be monitored, as institutional investors are typically the main investors in private assets (other investment funds, pension funds, insurance companies and OFIs). In addition, banks play a significant role in private finance, primarily through the provision of leverage. To allow for a comprehensive risk monitoring and assessment, it is important to enable adequate information, including on the volume and quality of lending by non-banks, as well as more detailed data on interconnections between private finance and other parts of the financial system.

Money market fund (MMF) regulation has been strengthened in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis. In the EU this has been achieved through the Money Market Fund Regulation of 2017. Our work at the ESRB and ESMA6 has subsequently identified a number of remaining weaknesses that emerged in the March 2020 dash-for-cash, which led to the ESRB’s 2021 recommendation on reforming MMFs7.

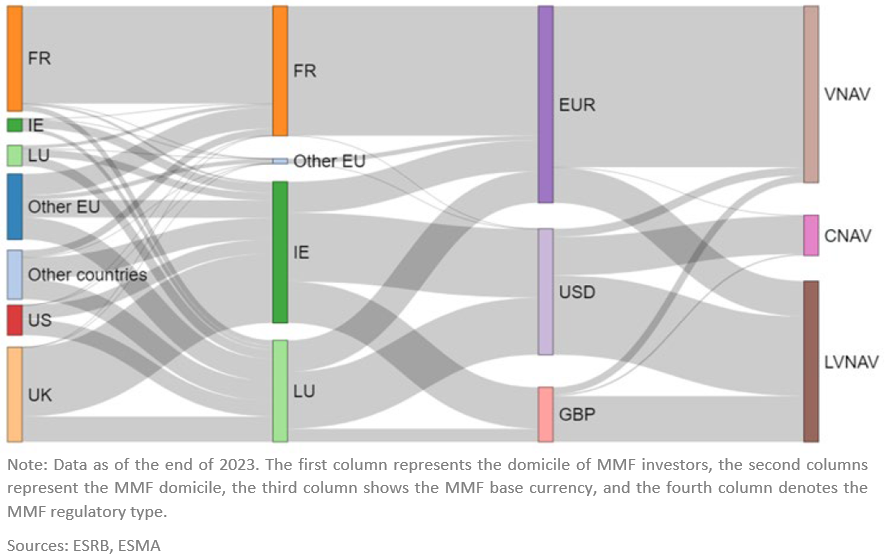

In addition to these weaknesses, our latest analysis of cross-border interconnections corroborates our 2021 call for further MMF reform: More than half of the investor base of EU MMFs is made up of non-EU investors, who mainly invest in MMFs denominated in non-EU currencies, and where the MMF itself is mainly of the type with higher susceptibility to liquidity issues. The latter are so-called Low-Volatility Net Asset Value funds, which have in that context gained most attention for the vulnerabilities that their design entails, as they offer a stable price to investors while investing in assets whose liquidity is limited, especially during stress periods.

Figure 3. MMF investors by country, region, currency and regulatory type

So far, the systemic importance of crypto-asset markets has seemed limited8. Overall market size was comparatively small, and the connections into the traditional system of finance were negligible.

The immense volatility of the crypto market notwithstanding, this assessment holds but requires monitoring. In terms of size, global crypto markets have recovered from the trough of the “crypto winter” of 2022 and are now back close to their previous peak at EUR 2.2tn in value outstanding. In addition, connections to traditional finance are growing since the US SEC’s decision in January 2024 to register crypto asset referenced Exchange Traded Products (ETPs). These are typically issued by large asset managers. Not yet a trend in Europe, the emergence of crypto ETPs has attracted sizeable inflows in the US in past months.

As volumes and linkages expand, it is key to monitor closely the various risks specific to this market9. Thus, stablecoins are a highly concentrated market and can act as a risk transmission channel to traditional finance. Also, we point to the growth of crypto derivatives, such as futures, options and “perpetual futures”, which can involve high leverage and whose trading volumes sometimes exceed spot volumes.

As policy discussions on the Savings and Investments Union and the NBFI macroprudential approach are progressing, a system-level view of non-bank finance in the EU points to the potential but also to the complexity of the market:

A wide range of external developments, including crypto assets, Artificial Intelligence, and also political and geopolitical events, posing new risks to be assessed and monitored. The EU urgently needs larger, more diverse and dynamic capital markets. Capital markets growing in size and complexity will need close risk monitoring, deeper economic analysis of new developments, and a robust macroprudential policy framework, even more so than today.

European Commission, “Targeted consultation document assessing the adequacy of macroprudential policies for non-bank financial intermediation (NBFI)”, Brussels, 22 May 2024.

Non-bank financial institutions include investment funds, money market funds and other financial intermediaries, such as securitisation vehicles or non-bank credit grantors.

ESMA provides a semi-annual monitoring of trends, risks and vulnerabilities in market and non-bank financing (ESMA Reports on Trends, Risks and Vulnerabilities), and in-depth analyses of key market issues (ESMA Risk Analysis).

European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB), “EU Non-bank Financial Intermediation Risk Monitor 2024”, No. 9, June 2024.

Market-based credit reflects the share of market-based debt finance (debt securities and non-retained securitised loans) relative to the total external debt of corporates, irrespective of which sector provided the credit. Non-bank credit reflects the relative share of investment funds and OFIs in providing debt financing to corporates compared with credit provided by all financial institutions (the non-bank financial sector and banks), irrespective of whether that financing is provided in the form of loans or debt securities.

ESMA, “ESMA opinion on the review of the Money Market Fund Regulation”.

ESRB, “Crypto-assets and decentralised finance: Systemic implications and policy options”, ESRB Task Force on Crypto-Assets and Decentralised Finance, May 2023

For a summary of risks see ESRB (2023)