This policy note is based on the keynote speech given at the joint Banco de España, Irving Fisher Committee on Central Bank Statistics and European Central Bank conference “External statistics after the pandemic: addressing novel analytical challenges” in Madrid on 12 February 2024. Further details on the conference are available here.

This note provides an analysis of euro area international financial flows against the backdrop of tightening monetary policy and heightened geopolitical tensions. Following a multi-year peak in 2021, there was a significant reversal in euro area international financial flows in 2022, marking the largest contraction since the global financial crisis, while in 2023 financial flows started to pick up again. These fluctuations were largely driven by developments in portfolio investment and foreign direct investment. The analysis of these components of the financial account has become increasingly complex in recent years, in particular owing to the expansion of international financial intermediation chains, which often involve non-bank entities located in international financial centres, including in some euro area countries. This note shows how new breakdowns of the euro area balance of payments and international investment position statistics facilitate an enhanced, albeit still imperfect, analysis of risk exposures and interconnectedness. It also outlines some areas with potential for further enhancing the statistical information available for such analysis and for improving the underlying statistical infrastructure.

As a long-standing user of external statistics, both in academia and as a central banker, I am very pleased to see that since the last conference on External Statistics held in Lisbon in February 2020, just before the onset of the pandemic, the richness and availability of external statistics – in particular for the euro area – has been further enhanced.1 This is of particularly high value for the analysis we do regularly at the ECB. At the same time, there are still significant measurement shortfalls in external statistics and many analytical hurdles to overcome, including specific challenges for the euro area.

My analysis focuses on euro area financial flows, in the current context of the monetary policy tightening cycle and elevated geopolitical tensions. In addition, I outline some areas where I see potential for further enhancing the statistical information available for such analysis and for improving the underlying statistical infrastructure.

The euro area is highly financially integrated, both internally and externally: an accurate measurement of financial linkages is key for our understanding of euro area exposures to external shocks and the international transmission of the ECB’s policies. The analysis of euro area cross-border financial linkages has become increasingly complex in recent years, in particular owing to the expansion of international financial intermediation chains, which often involve non-bank entities located in international financial centres, including in some euro area countries.2 At the same time, the ECB – together with the euro area national central banks – has developed new breakdowns of the euro area balance of payments and international investment position (b.o.p./i.i.p.) statistics that facilitate an enhanced, albeit still imperfect, analysis of risk exposures and interconnectedness.3

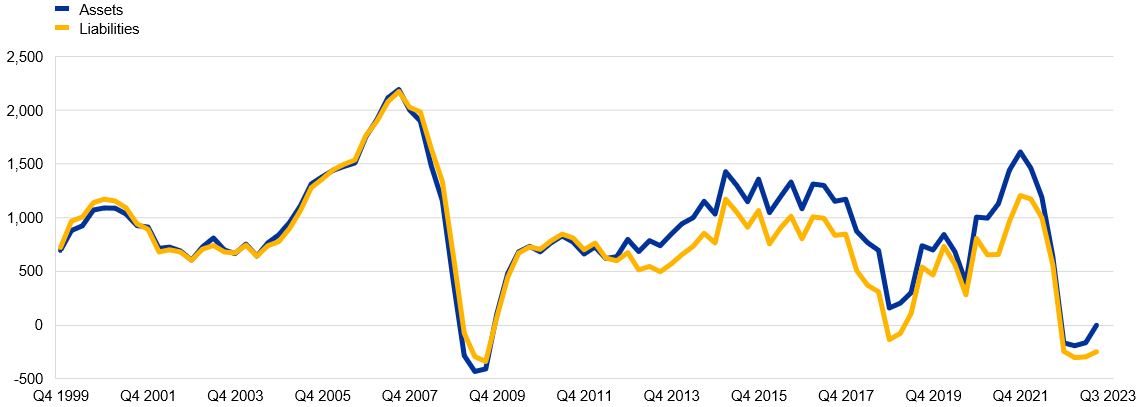

Euro area international financial flows sharply reversed in 2022 – from a multi-year peak observed in 2021 – into the largest retrenchment since the global financial crisis (Chart 1).4 The retrenchment affected both foreign assets and foreign liabilities, in line with their strong co-movement observed over the past decades. More recently, in 2023, euro area financial flows started to pick up again.

Chart 1: Euro area financial account

(four-quarter moving sums, EUR billions)

Source: ECB.

Notes: A positive (negative) number indicates cross-border net purchases (sales). Net financial derivatives are reported under assets. The latest observation is for the third quarter of 2023.

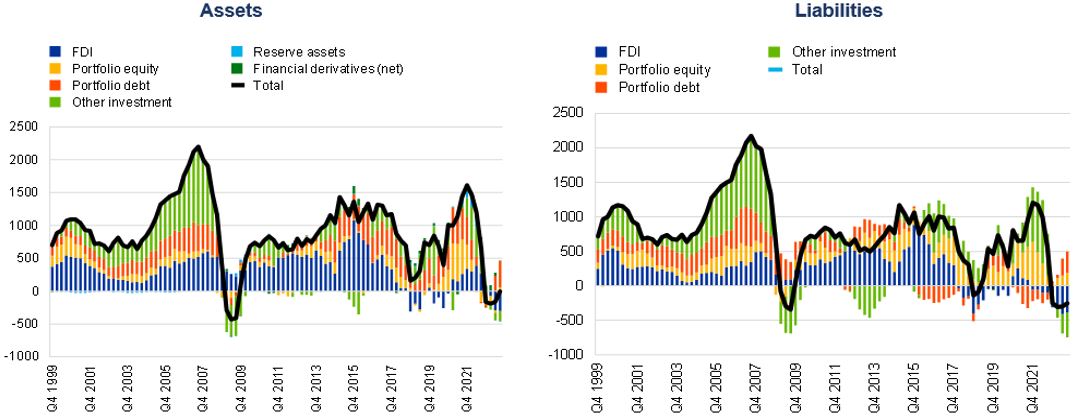

The swings in euro area international financial flows over the past few years were to a great extent driven by foreign portfolio investment and foreign direct investment (Chart 2).5 Accordingly, my analysis focuses on these two components of the financial account that – due to the intricacies of euro area financial intermediation – require a particularly careful analysis. To this end, I use the available detailed official statistics, but also draw on insights from research studies.

Chart 2: Euro area financial account

(four-quarter moving sums, EUR billions)

Source: ECB.

Notes: For assets, a positive (negative) number indicates net purchases (sales) of non-euro area instruments by euro area investors. For liabilities, a positive (negative) number indicates net purchases (sales) of euro area instruments by non-euro area investors. The latest observation is for the third quarter of 2023.

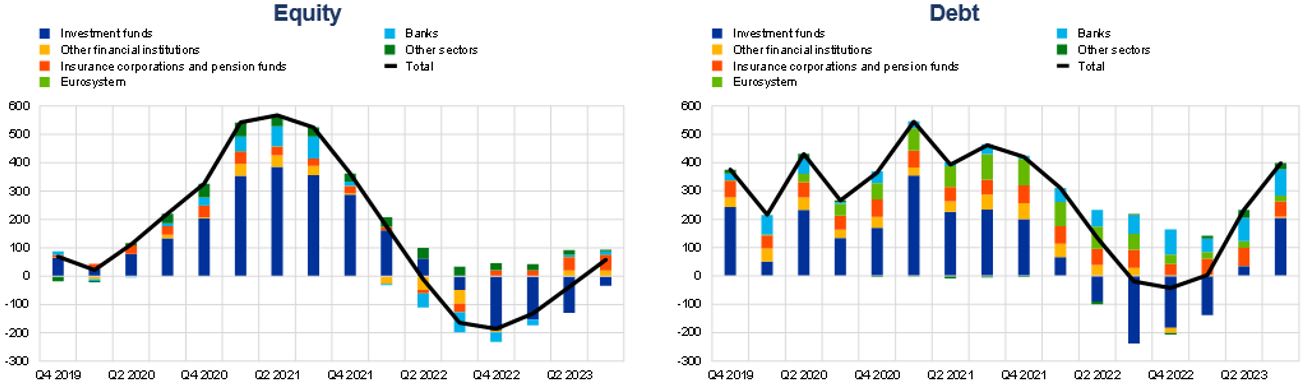

I start by examining detailed information at the euro area (resident) sectoral level to better understand the factors driving aggregate foreign portfolio investment flows. Focusing on the non-bank financial intermediaries sector provides valuable insights.

At a structural level, the sectoral breakdown reveals the predominance of the investment funds sector (including money market funds) as holders of portfolio investment securities issued by non-euro area residents. It accounts for 64% of total equity and debt holdings in the third quarter of 2023. It follows that an analysis of the cross-border investment patterns by investment funds is crucial, not only for assessing the exposures of the investment fund sector, but also for understanding those of the underlying investors. Insurance companies, pension funds and households are significant holders of euro area investment fund shares, while foreign investors residing outside the euro area are also major investors in euro area funds.6 Recent research shows that euro area investment funds are a source of portfolio diversification for the underlying euro area investors, in particular towards extra-euro area assets.7 For foreign investors, euro area investment funds not only provide exposure to euro area assets but also constitute intermediation vehicles for global portfolio investment.

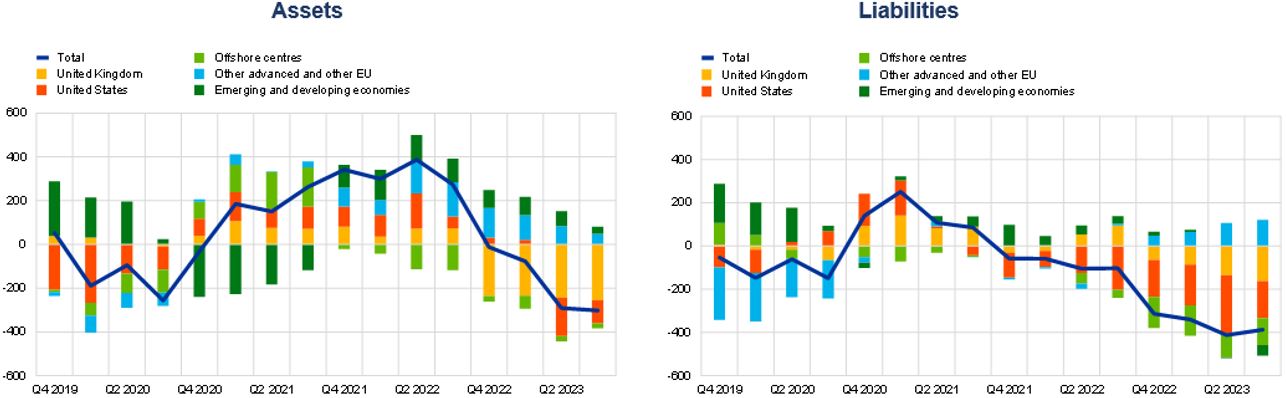

Investment funds account for a significant proportion of the fluctuations in international portfolio investment flows (Chart 3). This is consistent with a procyclical demand for investment fund shares, with the underlying investors strongly affected by shifts in global sentiment. This helps to explain the 2022 retrenchment, given the low risk appetite prevailing in global financial markets following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The data also confirm that insurance corporations and pension funds tend to be more stable investors, at least in relation to their direct holdings.8

Chart 3: Euro area portfolio investment assets by resident sector

(transactions; four-quarter moving sums, EUR billions)

Source: ECB.

Notes: For assets, a positive (negative) number indicates net purchases (sales) of non-euro area instruments by euro area investors. For liabilities, a positive (negative) number indicates net purchases (sales) of euro area instruments by non-euro area investors. The latest observation is for the third quarter of 2023.

While a structural analysis of the drivers of euro area portfolio flows is beyond the scope of this note, I would like to highlight that – apart from the geopolitical factors weighing on investor sentiment – the monetary policy tightening of the ECB may also have contributed to the retrenchment in portfolio flows. In fact, the shifts in investment patterns observed in 2022 marked an end to a protracted phase of large-scale portfolio rebalancing towards extra-euro area securities, which had started in 2014 when the ECB introduced negative interest rates and launched its asset purchase programmes.9 More recently, the net purchases of foreign securities by euro area investors rebounded amid the global shift in the interest rate environment, with higher interest rates especially prompting a step-up in international bond purchases.

On the liability side of euro area portfolio investment, investment funds played a similarly large role in the drying-up of foreign net purchases of euro area equities in 2022. The combination of the sizeable euro area investment fund industry and the strong extra-euro area investor base – especially for those funds based in Ireland and Luxembourg – amplifies euro area financial flows, particularly during times of sharp shifts in risk sentiment (Chart 4). At the same time, since the amplification in part reflects the pass-through holdings of external investors in external assets, the impact on euro area financial dynamics is overstated by focusing on un-adjusted measures.10

Chart 4: Euro area portfolio investment liabilities by resident sector

(transactions; four-quarter moving sums, EUR billions)

Source: ECB.

Notes: For liabilities, a positive (negative) number indicates net purchases (sales) of euro area instruments by non-euro area investors. Investment funds include money market funds. Other sectors include the Eurosystem, households and non-profit institutions serving households, insurance corporations and pension funds. The latest observation is for the third quarter of 2023.

Higher euro area interest rates and the ending of net asset purchases by the Eurosystem have visibly boosted the appetite of foreign investors for euro area debt securities since 2022 (Chart 4). This is a reversal of the pattern during the years 2014-2019 when foreign investors were large net sellers of euro area debt securities, especially sovereign bonds. That is, monetary policy clearly plays a significant role in determining net foreign debt inflows, via both the level of interest rates and balance sheet policies. In an environment of rising interest rates, foreign investors have turned into net buyers of euro area debt securities, especially sovereign bonds and bank bonds.

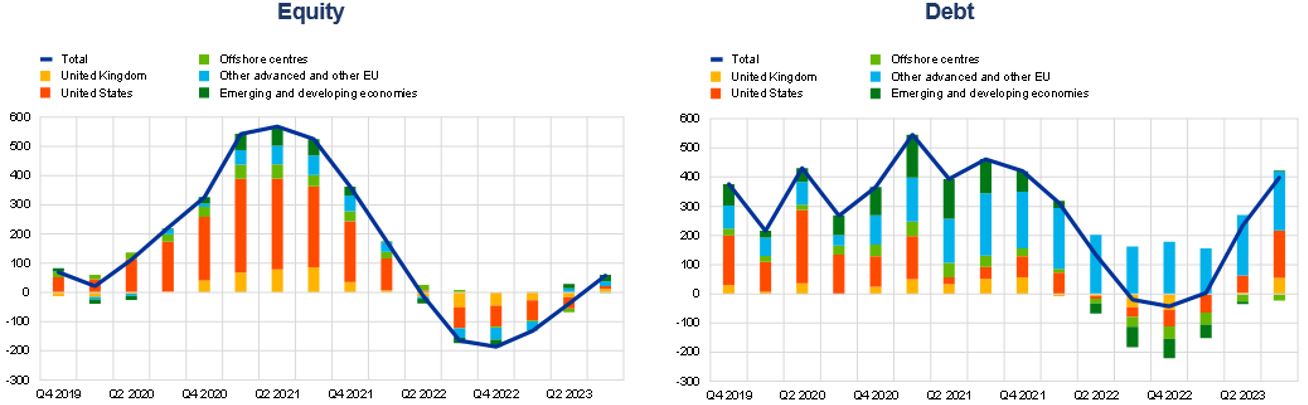

The new counterpart breakdowns available in the euro area b.o.p./i.i.p. allow for a better coverage of the geography of international financial flows, vis-à-vis both advanced economies and emerging market economies.11 These data reveal that in 2022 euro area investors reduced their exposures to equity securities in a broad-based fashion across geographic counterparts (Chart 5).12 The retrenchment was particularly pronounced vis-à-vis the United States and the United Kingdom.

Chart 5: Euro area portfolio investment assets by counterpart location

(transactions; four-quarter moving sums, EUR billions)

Source: ECB.

Notes: For assets, a positive (negative) number indicates net purchases (sales) of non-euro area instruments by euro area investors. “Other advanced and other EU” include Australia, Canada, Japan, Norway, South Korea and Switzerland as well as the non-euro area EU Member States and those EU institutions and bodies that are considered for statistical purposes as being outside the euro area, such as the European Commission and the European Investment Bank. “Emerging and developing economies” include all countries and country groups not shown in the chart, as well as unallocated transactions. The latest observation is for the third quarter of 2023.

For debt securities, the picture is more nuanced: during the retrenchment in 2022, euro area investors on balance sold a significant amount of securities issued by US and UK residents, while net purchases continued vis-à-vis other advanced economies and the non-euro area EU (Chart 5). The strong net sales of debt issued by emerging market economies and offshore financial centres were particularly striking, especially given their relatively small weight in the euro area portfolio. Among emerging market economies, these net sales were driven by disinvestments of securities issued in China, Mexico and Russia.13 While euro area net purchases of debt securities recovered strongly vis-à-vis most regions in 2023, the sentiment towards emerging economies and offshore financial centres remained muted.

While at first sight emerging economies and offshore financial centres may appear as rather unrelated investment destinations, these are in fact closely linked, since the debt securities issued in offshore financial centres are to a significant extent issued by subsidiaries of corporations based in emerging markets, particularly in China. Recent research finds that euro area and US investment in emerging market corporate bonds is substantially larger when investment in issuance by offshore subsidiaries of emerging market corporations is taken into account.14 For the euro area, estimates show that the “nationality-based” holdings of corporate debt securities of the BRICS countries are around six times higher.15 This example highlights the difficulty in tracing ultimate exposures across the financial intermediation chains. At the same time, it shows how ambitious research involving the careful merging of various datasets may provide complementary information to the public, which could lay the ground for future enhancements to official statistics.

While information on the geography of euro area portfolio investment assets has become increasingly rich, it is notoriously difficult to obtain a full grasp of the foreign holders of euro area securities.16 This relates to the phenomenon of globally missing assets, as the portfolio investment liabilities that are reported globally consistently exceed reported assets.17 This gap, in turn, can be linked to a significant degree to equity securities issued in the United States, Ireland and Luxembourg.18 There is a range of conjectures on the origins of the globally missing assets. A primary explanation relates to the non-reporting of assets held in custody abroad (so-called third party holdings), in particular by investors with no statistical reporting obligation such as households or non-financial corporations.19 Within the euro area, such third-party holdings are already reported by custodians as part of the securities holdings statistics, which increases the coverage of intra-euro area portfolio investment holdings. However, security holdings that are held in custody outside the euro area can at best be estimated.20 In closing this significant data gap, I see room for international initiatives to promote a comprehensive and granular reporting of third-party holdings (for instance in the context of the IMF’s Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey) by those countries with a strong custody industry.21

Taking a longer-term perspective, euro area foreign direct investment (FDI) flows were remarkably stable for decades, even during crisis times, before entering a phase of exceptionally large, positive flows from about 2015 (as shown in Chart 2). This was followed by a period of high volatility and – more recently – a strong retrenchment phase.22

As I have noted on previous occasions, the developments in FDI over the past decade have been very much driven by euro area financial centres due to the presence of multinational enterprises (MNEs) in these economies.23 MNEs tend to have complex organisational structures which frequently involve numerous legal entities, including special-purpose entities (SPEs), across various countries.24

While the interpretation of euro area headline FDI figures has not become easier over the years, more detailed sectoral and geographic breakdowns facilitate the analysis of FDI. Moreover, our understanding of euro area FDI is set to improve further in the near future, with the publication of a separate breakdown for SPEs in euro area b.o.p./i.i.p. statistics.

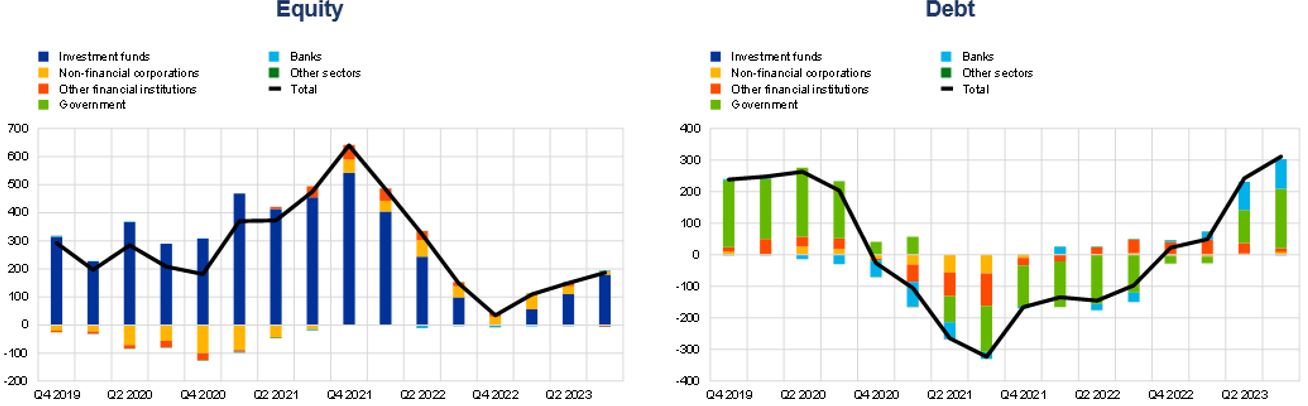

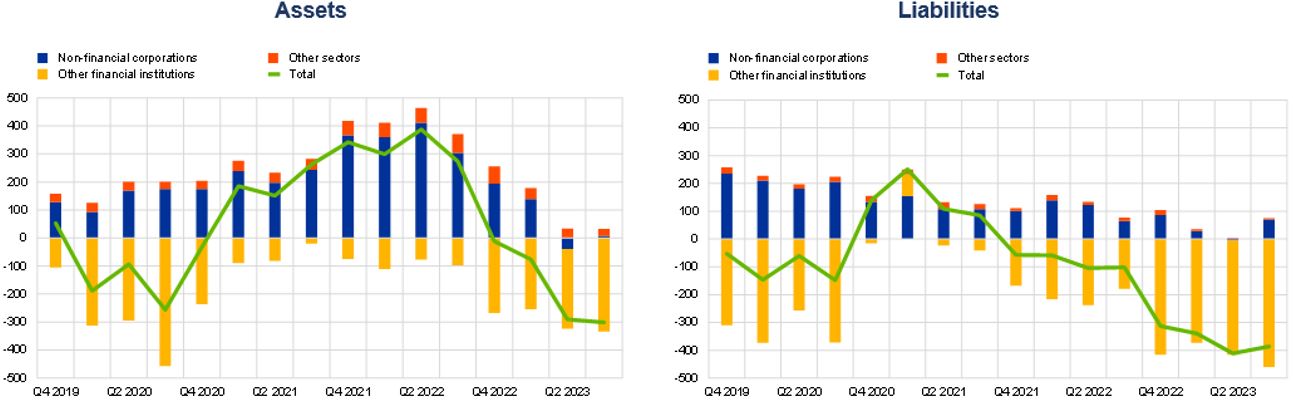

Taking a sectoral view of the retrenchment observed in euro area FDI since 2022 reveals the important role of the other financial institutions (OFI) category, which also includes SPEs and holding companies (Chart 6).25 The strong positive correlation between gross FDI asset and liability transactions related to OFIs suggests that these “financialised” flows often “pass through” the euro area without being absorbed in the domestic economy. Preliminary data suggest that SPEs represent around 30 per cent of euro area FDI asset and liability positions and 55 per cent of FDI assets and liability positions in the OFI sector. More insights on the role of SPEs in euro area cross-border statistics will become available with the publication of the b.o.p./i.i.p. dataset for SPEs this spring.

Chart 6: Euro area foreign direct investment by resident sector

(transactions; four-quarter moving sums, EUR billions)

Source: ECB.

Notes: For assets, a positive (negative) number indicates net purchases (sales) of non-euro area instruments by euro area investors. For liabilities, a positive (negative) number indicates net purchases (sales) of euro area instruments by non-euro area investors. “Other sectors” include all institutional sectors not shown in the chart. The latest observation is for the third quarter of 2023.

In contrast to OFI-related FDI flows, the FDI flows of the non-financial corporate sector are mainly driven by the euro area countries outside the group of financial centres and hence tend to be more closely related to developments in the real economy. Accordingly, while there was no large-scale retrenchment, the recent slowdown in this sector’s FDI transactions appears to be consistent with lower global and euro area growth momentum and might also provide tentative signs of companies pulling back from overseas direct investment amid heightened geopolitical risks.26

The geographic breakdown of FDI flows brings additional insights (Chart 7). The recent retrenchment occurred vis-à-vis counterparts in the United States, United Kingdom and in offshore financial centres, which suggests a close relation to MNE operations, particularly in combination with the sectoral evidence presented before. Having said this, euro area FDI asset flows to other destinations have proven to be more resilient in recent years, albeit on a much smaller scale.

Chart 7: Euro area foreign direct investment by counterpart location

(transactions; four-quarter moving sums, EUR billions)

Source: ECB.

Notes: For assets, a positive (negative) number indicates net purchases (sales) of non-euro area instruments by euro area investors. For liabilities, a positive (negative) number indicates net purchases (sales) of euro area instruments by non-euro area investors. “Other advanced and other EU” include Australia, Canada, Japan, Norway, South Korea and Switzerland as well as the non-euro area EU Member States and those EU institutions and bodies that are considered for statistical purposes as being outside the euro area, such as the European Commission and the European Investment Bank. “Emerging and developing economies” include all countries and country groups not shown in the chart, as well as unallocated transactions. The latest observation is for the third quarter of 2023.

Similarly to portfolio investment, even these more detailed FDI data remain insufficient to fully look through the often complex cross-border chains to identify the ultimate investor countries and ultimate host economies involved in FDI relationships. This is a notoriously difficult task, not only due to the complex ownership structures of MNEs, but also because it requires very comprehensive information. Sharing data among national statisticians across borders could be helpful (as further elaborated on below). Nonetheless, some research-based advancements in identifying the ultimate countries involved in an FDI relationship provide useful insights.27 Data on inward FDI on an ultimate basis reveal, for example, a much larger role of the United States as an investor in the EU compared to the official (immediate counterparty basis) data.28

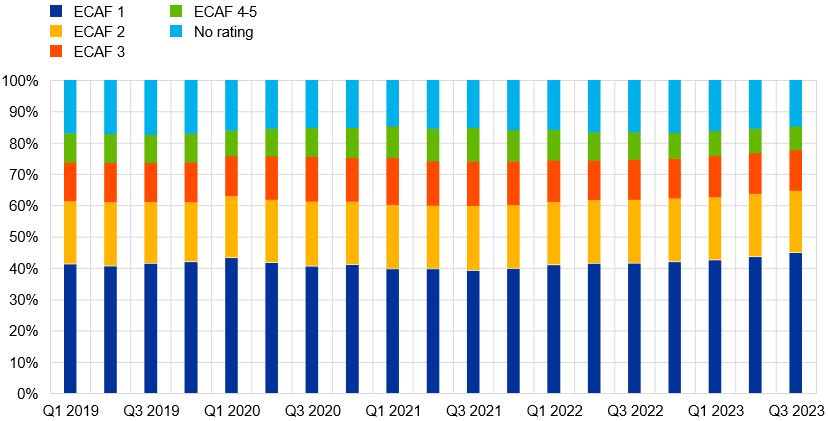

Combining b.o.p./i.i.p. statistics with security-level data such as the European System of Central Banks’ (ESCB) Securities Holdings Statistics allows for a granular analysis along various dimensions, such as currency, issuing entity and security characteristics, including the rating.29 For the latter, experimental ECB data on euro area portfolio investment assets show an increase in the share of high-rated debt securities since 2021, in line with a preference for safer assets during times of elevated risk aversion (Chart 8).30

Chart 8: Euro area portfolio investment debt asset position by rating category

(percentage shares of outstanding amounts)

Source: ECB.

Notes: Experimental data following Rodríguez Caloca, A., Radke, T. and Schmitz, M. (2021). The ratings categories are drawn from the Eurosystem Credit Assessment Framework (ECAF). The ECAF provides a harmonised rating scale of five credit quality steps. The first step includes securities rated from AAA to AA-, the second from A+ to A-, the third from BBB+ to BBB-. In addition, the fourth category includes all rated securities with a rating below credit quality step three and the fifth category reflects those securities without a rating. The latest observation is for the third quarter of 2023.

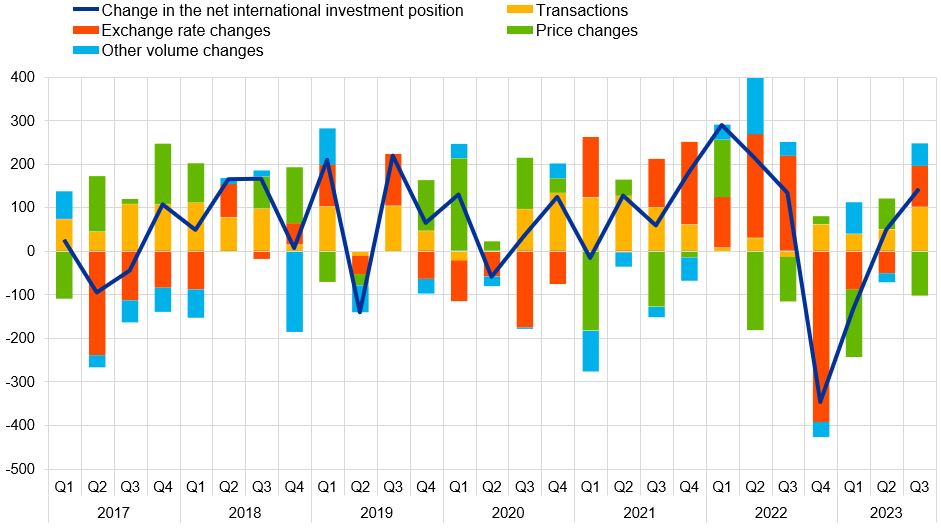

In addition, and this also stressed in the ongoing update of the balance of payment manual, it is very useful to have a fully integrated view of the international investment position, showing how the transmission of financial shocks propagates through the valuation channel arising from exchange rates and other asset price movements to an economy’s external balance sheet.31 Unlike when I started doing research on this topic, nowadays such data are readily available in the official statistics of many economies, including for the euro area, with a considerable degree of detail, and show, for example, the importance of exchange rate-induced valuation effects (Chart 9).

Chart 9: Changes in the net international investment position of the euro area

(outstanding amounts; EUR billions)

Source: ECB.

Notes: The latest observation is for the third quarter of 2023.

To enhance the analysis of globalisation-related phenomena, and in particular to isolate the impact of MNEs, I support the plans of the ESCB to establish new data on foreign-controlled non-financial corporations in the balance of payments and the financial sector accounts. It would also be essential for such data to be available for the non-financial accounts, in order to observe the impact of MNEs on production and capital formation patterns. In this context, I would like to stress once more that it is analytically very useful to have fully consistent data on external accounts and domestic sectoral accounts, as is the case for the euro area datasets on b.o.p. and quarterly sector accounts. This supports the analysis of interconnectedness and helps to identify domestic sector imbalances that ultimately drive external imbalances.32

More generally, in terms of statistical infrastructure, I would like to highlight again that further efforts are needed to improve the analytical value of macroeconomics statistics. In my view, to keep official statistics fit for policy analysis, these need to enable a fast response to crises and keep pace with the rapidly evolving global activities of MNEs and financial intermediaries. For example, I am very much in favour of the development and use of experimental statistics to boost statistical agility. In this context, the pandemic has shown the usefulness of “non-standard” higher-frequency data sources, for instance to enhance our understanding of labour market dynamics.

Another improvement that is worth considering is facilitating the safe exchange of confidential statistical information for well-justified statistical purposes across borders, especially within the ESCB/European Statistical System (ESS). This can be achieved by a sound and supportive legal basis, coupled with robust and safe information technology systems supporting the exchange of data. This would minimise the risks of unlawful disclosures, while maximising the benefits of synergies through collaboration between statistical authorities.33

As I have advocated before, there is a strong case for exploring avenues to collect data on internationally active, large MNEs in a centralised way, at the EU rather than national level. This could eliminate information gaps and overlaps across countries and ensure a more timely, complete and consistent cross-country recording of the activities of MNEs. A coordinated approach across the EU could be a win-win situation, as it would reduce the statistical reporting burden of MNEs by removing the need to complete questionnaires from 27 Member States in more than 20 languages. This streamlined process would not only benefit the MNEs themselves but also the statistical authorities responsible for collecting and analysing the data. It would improve timeliness, enhance the accuracy of reporting and ultimately contribute to a more efficient and effective system of data management. This is already being pursued by the ESCB in relation to the banking industry through standardising area-wide data reporting by banks.34

In this note I have focused on euro area financial flows in the current context of the monetary policy tightening cycle and geopolitical tensions. I have stressed the usefulness of available data for the regular analysis we do at the ECB, but I have also highlighted the areas where measurement issues still hamper our full understanding of portfolio investment and foreign direct investment exposures.

Further efforts are needed to improve the analytical value of external statistics and this can be achieved by enhancing the underlying statistical infrastructure.

See Lane, P.R. (2020), “The analytical contribution of external statistics: addressing the challenges”, keynote speech at the Joint European Central Bank, Irving Fisher Committee and Banco de Portugal conference on “Bridging measurement challenges and analytical needs of external statistics: evolution or revolution?”, 17 February.

See Lane, P.R. and Milesi-Ferretti, G.M. (2018), “The External Wealth of Nations Revisited: International Financial Integration in the Aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis,” IMF Economic Review, Vol. 66, No 1, International Monetary Fund, pp. 189-222.

The new data reported in accordance with the amended ECB External Statistics Guideline ECB/2018/19 include additional breakdowns by resident sector, counterpart country and foreign direct investment debt instruments. The new series is currently available for the euro area aggregates as of the first quarter of 2019 and data for earlier periods will be made available in the course of 2024. Additional information on the euro area balance of payments and international investment position statistics can be found on the ECB’s website.

See Emter, L., Schiavone, M. and Schmitz, M. (2023), “The great retrenchment in euro area external financial flows in 2022 – insights from more granular balance of payments statistics”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 4, ECB.

Transactions in the category “other investment” also reversed from high positive values in 2022 – in particular on the liability side – mainly owing to a decline in the deposits of non-euro area residents held with the Eurosystem.

See Carvalho, D. (2022), “The portfolio holdings of euro area investors: Looking through investment funds,” Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 120, pp. 102-519 and Beck, R., Coppola, A., Lewis, A., Maggiori, M., Schmitz, M. and Schreger, J. (2023), “The Geography of Capital Allocation in the Euro Area”, working paper available at SSRN.

See Carvalho, D. and Schmitz, M. (2023), “Shifts in the portfolio holdings of euro area investors in the midst of COVID-19: looking through investment funds”, Review of International Economics. Vol. 31, Issue 5, pp. 1641-1687 and Beck, R., Coppola, A., Lewis, A., Maggiori, M., Schmitz, M. and Schreger, J. (2023), op. cit.

See Timmer, Y. (2018), “Cyclical investment behaviour across financial institutions”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 129, No 2, pp. 268-286.

The ECB’s asset purchase programme was initiated in mid-2014, while its pandemic emergency purchase programme was launched in March 2020. Net asset purchases under both programmes were discontinued in 2022. See Cœuré, B. (2017), “The international dimension of the ECB’s asset purchase programme”, speech given at the Foreign Exchange Contact Group meeting, 11 July; Lane, P.R. (2019), “The international transmission of monetary policy”, keynote speech at the CEPR International Macroeconomics and Finance Programme Meeting, 14 November; and Bergant, K., Fidora, M. and Schmitz, M. (2020), “International capital flows at the security level: evidence from the ECB’s Asset Purchase Programme”, Working Paper Series, No 2388, ECB, Frankfurt am Main.

See Beck, R., Coppola, A., Lewis, A., Maggiori, M., Schmitz, M. and Schreger, J. (2023), op. cit.

The list of counterpart countries now includes for instance all G-20 and EU countries outside the euro area. In particular, information became available for a number of additional advanced economies (Australia, Norway and South Korea) and emerging market economies (Argentina, Indonesia, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and Türkiye).

On the determinants of the geography of the equity holdings of euro area investors, see Lane, P.R. and Milesi-Ferretti, G.M. (2007), “The International Equity Holdings of Euro Area Investors,” in The External Dimension of the Euro Area (Di Mauro, F. and Anderton, R. eds), Cambridge University Press.

For details on how euro area investment in Russia evolved following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, see Emter, L., Fidora, M., Pastoris, F. and Schmitz, M. (2022), “Euro area linkages with Russia: latest insights from the balance of payments”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 7, ECB.

See Bertaut, C. C., Bressler, B. and Curcuru, S. (2019), “Globalization and the Geography of Capital Flows,” FEDS Notes, Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Coppola, A., Maggiori, M., Neiman, B. and Schreger, J. (2021), “Redrawing the Map of Global Capital Flows: The Role of Cross-Border Financing and Tax Havens”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 136(3), pp.1499-1556 and Beck, R., Coppola, A., Lewis, A., Maggiori, M., Schmitz, M. and Schreger, J. (2023), op. cit.

The BRICS countries are Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

The ECB provides estimates for euro area portfolio investment liability positions by counterparty. However, these are subject to uncertainty as securities are regularly traded in secondary markets and held via custodians and other financial intermediaries.

See Milesi-Ferretti, G.M. (2023), “Many Creditors, One Large Debtor: Understanding The Buildup of Global Stock Imbalances after the Global Financial Crisis,” IMF Economic Review.

See Milesi-Ferretti, G.M. (2024), “Missing assets: Exploring the source of data gaps in global cross-border holdings of portfolio equity”, mimeo, Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy, The Brookings Institution, and Beck, R., Coppola, A., Lewis, A., Maggiori, M., Schmitz, M. and Schreger, J. (2023), op. cit.

See Zucman, G. (2013), “The missing wealth of nations: Are Europe and the US net debtors or net creditors?”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(3), 1321-1364.

See Bui Quang, P. and Gervais, E. (2019), “How to identify “hidden securities assets” in the Balance of Payments: methods of Bank of France”, BIS IFC Bulletin, No 49.

See Diz Dias, J. et al. (2024), “Where are the hidden securities in external statistics?”, mimeo, ECB.

Foreign direct investment-related flows were traditionally considered to be the least volatile category of international capital flows. See, for example, Eichengreen, B., Gupta, P. and Masetti, O. (2018), “Are Capital Flows Fickle? Increasingly? And Does the Answer Still Depend on Type?”, Asian Economic Papers, Vol. 17(1), pp. 22-41. However, in recent years the strong role of multinational enterprises has been accompanied by increased volatility, especially for small open economies. See, for example, Di Nino, V., Habib, M. and Schmitz, M. (2020), “Multinational enterprises, financial centres and their implications for external imbalances: a euro area perspective”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 2, ECB.

Euro area financial centres commonly include Belgium, Cyprus, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta and the Netherlands.

SPEs located in euro area financial centres typically hold equities, manage debt issuance and allocate funding across parent and subsidiaries.

See Emter, L., Schiavone, M. and Schmitz, M. (2023), op. cit.

See Attinasi, M.G., Ioannou, D., Lebastard, L. and Morris, R. (2023), “Global production and supply chain risks: insights from a survey of leading companies”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 7, ECB.

See Brew, K. et al. (2023), “Experimental Ultimate Host Economy Statistics for U.S. Direct Investment Abroad”, BEA Working Paper Series, WP 2023-9; Figueira, C. (2023), “Where is the real impact of Foreign Direct Investment? – The case of the Portuguese outward foreign direct investment”, mimeo, Banco de Portugal; and Gómez-Llabrés, C., Pastoris, F. and Schmitz, M. (2023), “Who stands behind European FDI investors? A novel characterisation of pass-through within the EU”, BIS IFC Bulletin, No 58.

See Eurostat (2023), US remains top EU foreign ultimate investment partner, 13 May.

See Rodríguez Caloca, A., Radke, T. and Schmitz, M. (2021), “The more the merrier: enhancing traditional cross-portfolio investment statistics using security-by-security information”, BIS IFC Bulletin, No 55.

Further developments of approaches combining micro and macro data, for example to measure euro area portfolio investment holdings of sustainable debt securities, will be very much welcome (see “Experimental indicators on sustainable finance” on the ECB’s website). More broadly, the data needs in macroeconomic statistics to cover climate change and sustainable finance have become very apparent in recent years. These include, for instance, the recommendations of the third data gaps initiative regarding climate change and FDI statistics presenting the associated carbon footprints as well as physical and transition risks. Official statistics in this field are needed to assess the social and economic impact of climate change and monitor the financial vulnerabilities stemming from physical and transitional risks.

See Lane, P.R. and Milesi-Ferretti, G.M. (2007), “A Global Perspective on External Positions”, in Clarida, R. H. (ed.), G7 Current Account Imbalances: Sustainability and Adjustment, National Bureau of Economic Research, pp. 67-102.

See Allen, C. (2019), “Revisiting External Imbalances: Insights from Sectoral Accounts”, Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 96, pp. 67-101.

See Committee on Monetary, Financial and Balance of Payments Statistics (2023), Opinion on the Exchange of Confidential Statistical Information (ECI) on European Statistics for statistical purposes between the ESS and the ESCB, 12 June.

See “Making banks’ data reporting more efficient” on the ECB’s website.