Looking beyond the short-term economic shock, the Covid-19 pandemic and the exceptional health protection measures introduced to contain the virus raise many questions as to the lasting consequences of the crisis. The issue of zombie firms, which is far from new, has taken on a whole new dimension, as their weight in developed economies has progressively increased since the 1980s. Massive public interventions to tackle the effects of the pandemic, whether by governments – debt moratoriums, cancellations of employer social security contributions, widespread use of short-time working schemes, etc. – or by central banks – increase and prolongation of asset purchases schemes – could result in keeping non-viable companies afloat, raising fears of a zombification of economies.

A zombie firm is generally defined as any firm that is active in the market but with low productivity, high debt and poor profitability. The definition and measurement of the phenomenon are not subject to a widespread consensus. Amongst the existing versions, we would refer in particular to that of the Adalet McGowan et al (2017), who define a zombie firm as one that has existed for more than ten years and whose operating income has not covered debt servicing costs for a period of more than three consecutive years. Avouyi-Dovi et al (2017) use another definition, that proposed by Caballero et al (2008) in their pioneering article on zombie firms in Japan: a zombie firm refers to a company that is fragile but that benefits from particularly favourable financing terms.

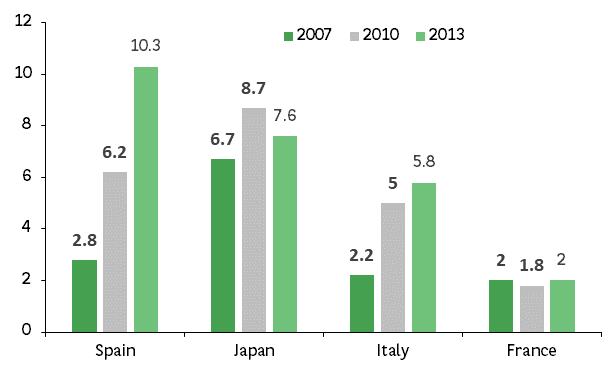

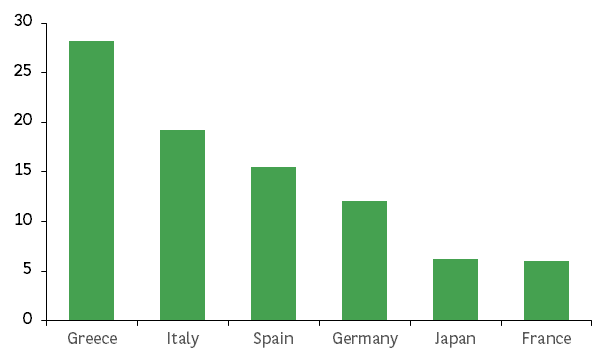

Although there are differences in estimates of their number, the rising trend in the share of zombie firms in advanced economies is widely recognised. This said, as demonstrated by the work of McGowan et al (2017), the picture varies considerably across European countries (see chart 1 and 2). The proportion in Spain (at around 10% in 2013) is significantly higher than in Italy or in France. Greece is the European economy with the greatest share of zombie firms. This hierarchy has been confirmed by the work of Hallak et al (2018).

Chart 1: share of zombie firms (% of total firms)

Source: Adalet McGowan et al (2017), OECD

Chart 2: share of capital sunk in zombie firms in 2013 (%)

Source: Adalet McGowan et al (2017), OECD

The zombification phenomenon has grown in scale since the 2000s, mirroring the earlier pattern in Japan. It should be noted that in the early 1990s Japan suffered a long deflation of real estate and equity prices, which undermined the value of collateral. Numerous analyses of the situation in Japan have highlighted the role of the lack of a rapid restructuring of banks following the bursting of the bubble and the rise in non-performing loans. The authorities’ response was thus too late and too timid. In order to avoid booking losses, Japanese banks continued to lend to unprofitable firms (Caballero et al, 2008). Thus, zombification could result from banks’ difficulties, particularly the most vulnerable ones for which making non-profitable loans remains the most viable solution.

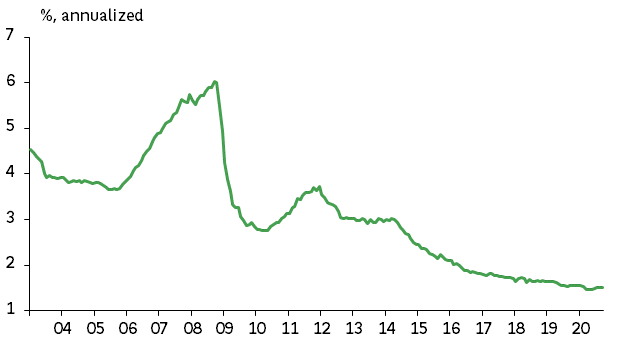

According to some authors, one of the main reasons for the proliferation of zombie firms in Europe, is the rapid and long lasting fall in interest rates since the early 1980s which has reduced financial pressures on all companies. Massive interventions by the European Central Bank (ECB), through cuts in its policy rates and a substantial asset purchasing programme (Quantitative Easing), have fed through into the loans granted to non-financial companies in the Eurozone, whose borrowing costs have fallen in a virtually continuous manner (Chart 3). The fall in interest rates may have thus encouraged increased financial risk-taking by firms that would have behaved differently had rates been higher.

Chart 3: average cost of new loans to NFCs in the Eurozone

Source: European Central Bank

However, the link between low interest rates and zombie firms seems somewhat too reductionist – particularly in the Eurozone – and is not fully established in the literature (Laeven et al, 2020). Furthermore, the weight of zombie firms varies significantly between the countries in the Eurozone, even though member States all share the same monetary policy. Thus it is difficult to blame low interest rates as the only catalyst for zombification.

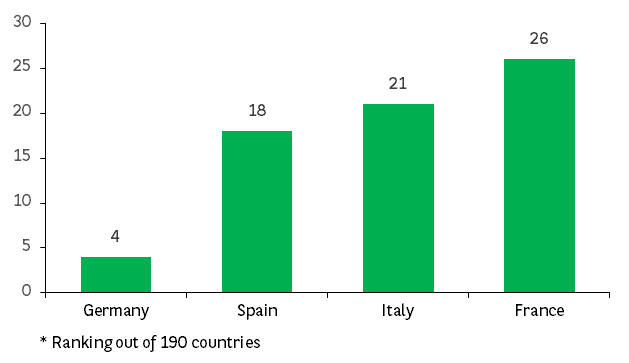

Several studies also stress the importance of the way in which struggling companies are dealt with in different countries. When the restructuring system is efficient, with relatively short and low-cost procedures, the reallocation of bank loans from struggling firms to more productive firms is quicker and the depreciation of assets is more limited. Conversely, when the system is less efficient, the process of “creative destruction” is held back. According to some authors, if “losses” are considered to be significant by banks, it may be in their interest to continue to lend to these vulnerable companies (Andrews and Petroulakis, 2017). This perpetuates the zombification cycle. On this point, and based on World Bank estimates, we can see major differences between European countries, with France and Italy both having long bankruptcy processes (over 18 months on average). Nonetheless, these results vary from one estimate to the next. The OECD, for instance, puts France in a higher position when it comes to bankruptcy procedures.

Chart 4: Efficiency of bankruptcy procedures: World Bank ranking*

Note: The World Bank index combines a number of indicators including the duration and cost of the process, together with qualitative information on the administrative management of these procedures. The higher the position in the rankings, the more efficient the bankruptcy procedure. For a detailed methodology, see https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/methodology/resolving-insolvency

Source: Refinitiv, World Bank.

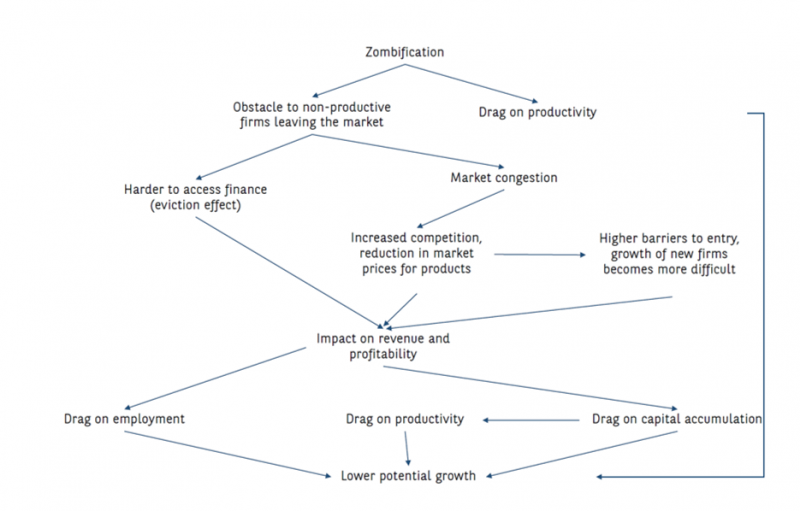

The increase in the number of zombie firms could have contributed to the downward trend in potential growth in OECD countries since the end of the 1990s, through two channels: the slowdown in total factor productivity (TFP) and lower business investment. Before becoming zombies, companies experience a deterioration in profitability, productivity and investment levels. Once they have become zombies, these firms remain less productive and tend to invest less than other companies (Avouyi-Dovi et al, 2017), which slows down productivity gains in the economy.

Maintaining non-viable firms in the market also creates congestion effects in the real economy: an increase in competition, which, without stimulating innovation, puts downward pressure on prices and thus affects profitability at unchanged costs. This also raises barriers to entry for new market entrants. Moreover, inefficient allocation of resources can, by extension, reduce productivity gains, as seen in southern Europe (Gopinath et al, 2017). In parallel, some studies suggest a crowding-out effect regarding the banking system (Andrews and Petroulakis, 2017): supporting zombie firms makes it harder, both directly and indirectly, for viable firms to access credit.

Figure 1: Macroeconomic impact of zombification on potential growth

Source: BNP Paribas

II. Would the COVID19 shock accelerate the zombification process?

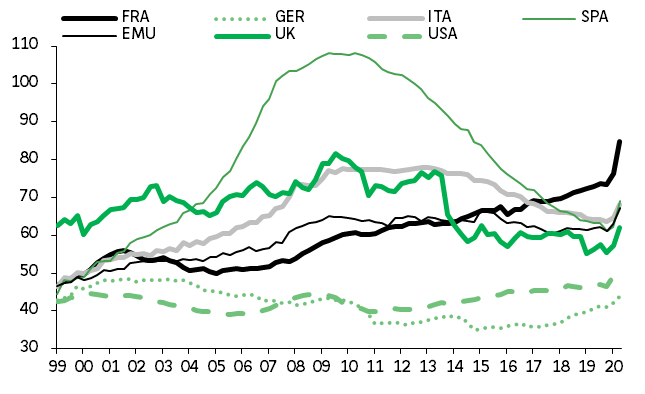

The overall financial position of European non-financial companies (NFCs) had improved since the 2008 crisis, in terms of their level of indebtedness, which has fallen in virtually all European countries (Chart 5). However, the Covid-19 pandemic has hit companies’ balance sheet. In 2020, NFC debt started to rise again, steeply, against the background of the crisis – driven notably by the substantial loan guarantee schemes introduced by governments.

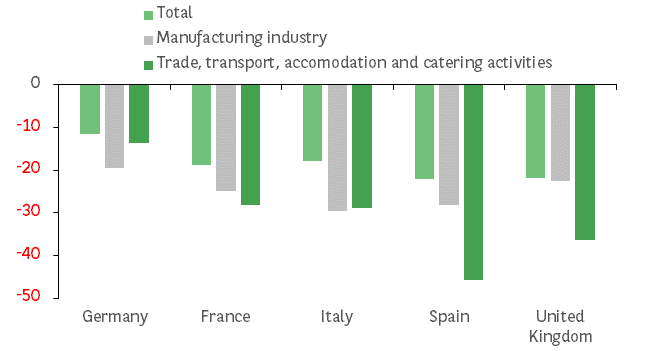

By sector, services have been harder hit by health restrictions than industry, especially in countries where these measures were the most stringent (France and Spain for example). Transport services, retail and hotels and restaurants displayed a particularly sharp fall in their added value during the first half of 2020 (Chart 6).

Firms in these sectors may therefore face a greater lack of liquidity than others, given the rapid drop in their revenues and the limited capacity to adjust their costs in the short term (even though short-time working schemes helped mitigate these costs to some extent). If these same companies faced financial difficulties before the crisis, these liquidity issues could, in the end, increase the risk of defaults.

Chart 5: NFCs debt ratio (% of added value)

Source: BNP Paribas

Chart 6: Change in value added between Q4 2019 and Q2 2020 (in %)

Source: BNP Paribas

Measures introduced by national governments, such as the massive use of short-time working and government-guaranteed lending by banks, seem, however, to have significantly reduced liquidity risks for European companies.

Overall, the exceptional lockdown measures introduced by governments make it difficult at this stage to distinguish between companies suffering only from liquidity problems and those that are insolvent. More precisely, until the economic situation has been fully normalised it will probably be too soon to draw such a distinction and sort the firms worthy of support from the rest.

The Covid-19 crisis raises twin fears: a wave of business failures on the one hand, or an insufficient number on the other. The smaller the wave, the greater the risk of zombification. However, we do not believe that one should worry (or at least not yet) about this political dilemma, which opposes on the one hand massive indiscriminate support that runs the risk of fuelling zombification, and on the other more limited support, allowing creative destruction but at the cost of higher unemployment and the loss of some viable businesses. Faced with the risk of zombification and the benefit of protecting productive and human capital, the latter wins out. The risk of feeding zombification is a lesser evil than that of destroying ‘good’ capital, especially as the former can be managed further down the line whilst the latter has bigger immediate and long-term consequences, which will be harder to reverse.

Without massive fiscal support, the collapse of European economies would have been much worse than it has been. Financially healthy and productive companies could have been forced to the wall by temporary cash flow problems. The social consequences of the crisis, through a steeper increase in unemployment, would have been even longer lasting (particularly if one acknowledges Europe’s imperfect labour mobility between sectors and countries). Concomitantly, the very flexible and accommodating monetary policy from the ECB – and other major central banks – has allowed a widespread decrease in interest rates across a broad spectrum of maturities for all economic agents. In particular, this has facilitated fiscal support. Without it, sovereign spreads (the differences in yields on different countries’ government debt) would have widened, the risk of financial fragmentation would have resurfaced and companies in the more vulnerable nations would have suffered for a long time to come.

Then, once the shock had eased and public support been scaled back, the European economy would have remained in a weakened state with corporate debt remaining high. Long-term unemployment could then have taken hold and business bankruptcies seen significant increases. Although business failures have so far been limited by public measures to support cash flow and temporary amendments to the legal framework for bankruptcy procedures – notably through waiving of the requirement for directors to declare a cessation of payments – this is only delaying the inevitable for a number of companies (De Moura Fernandes, 2020). As we come out of the crisis, attention will turn to borrowing levels at European companies. Already, one can expect a sharp rise in business bankruptcies in Europe in 2021 (Lemerle, 2020): Germany (+12% compared to the 2019 level), France (+25%), Italy (+27%) and Spain (+41%). The increases in company bankruptcies and indebtedness will have fewer macroeconomic consequences in case of efficient debt restructuring or liquidation framework in place (Jordà, 2020). In this area, Europe is relatively well positioned.

If the risk of increased zombification cannot be ruled out following the Covid-19 crisis, what can be done to address it? In the near future, one direct remedy is to strengthen firms’ balance sheets. This must happen through a strengthening of capital via, for example, participating loans – as included in the France Relance programme – or the transformation of government-guaranteed loans into subsidies, a possibility also raised in France. It might also take the form of a restructuring of the debts of companies considered as viable. More broadly, in terms of macroeconomic policy, improvements to recovery and liquidation processes2 also form part of the measures to be taken. In the longer term, policies on competition, innovation, training and professional mobility are also powerful ways to tackle zombification, to the extent that they improve the creative destruction process and an efficient (re)allocation of resources. The outcome is that it is easier for firms to enter and leave the market. Taken together, such policies would boost potential growth in Europe, which represents the best way of holding back zombification.

Andrews, D. and F. Petroulakis (2017), Breaking the shackles: zombie firms, weak banks and depressed restructuring in Europe, BIS background paper, November.

Avouyi-Dovi, S., et al. (2017), Y-a-t-il des entreprises zombies en France?, Bloc-notes Eco, Banque de France, March.

Caballero, R.J., et al. (2008), Zombie lending and depressed restructuring in Japan, American Economic Review.

De Moura Fernandes, B. (2020), Défaillances d’entreprises en Europe: les amendements des procédures juridiques repoussent temporairement l’échéance, Coface, June.

Hallak, I., et al. (2018), Fear the walking dead? Incidence and Effects of Zombie Firms in Europe, European Commission.

Laeven, L. et al. (2020), Zombification in times of pandemic, VoxEU CEPR, October.

Jordà, O. (2020), Zombies at large? Corporate debt overhang and the macroeconomy, Fed San Francisco, December.

Lemerle, M. (2020), Calm before the storm: Covid-19 and the business insolvency time bomb, Allianz Research, July.

McGowan, A., et al. (2017), The walking dead? Zombie firms and productivity performance in OECD countries, OECD working papers.

This policy brief is a summary of longer article written by the BNP Paribas Economics team. The full article can be found here.