This policy brief is based on European Economy Discussion Paper 218. This research was funded through an ECFIN Research Project ECFIN_2023_VLVP_0063. The views expressed in this brief are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of the European Commission.

Abstract

Concerns about fiscal sustainability and worsening balance sheet conditions of major banks triggered a doom loop between banks and sovereigns during the 2010-2013 sovereign debt crisis. Despite closer financial integration and additional institutional safeguards, the home bias, i.e. domestic bank holdings of domestic sovereign debt, is still high in most EU countries and raises concerns on the incentive of governments to consolidate debt. We examine the effects of home bias on fiscal sustainability in EU countries. Using an extension of an IMF database on sovereign debt holdings by Asonuma et al. (2015) and a novel methodology, we find that a higher home bias does not necessarily reduce the reaction of governments to public debt. The reason is that a developed banking system allows sovereigns to raise more public debt domestically at acceptable conditions to support economic stabilisation. An increased presence of foreign banks has a benign effect on sustainability by reducing governments’ debt bias, but state-owned banks reduce it. Developing financial markets further through the completion of the Banking and Capital Markets Unions in the EU could help countries in the trade-off between economic stabilisation and debt sustainability, while bringing in more foreign banks might enforce stronger fiscal discipline.

One of the lessons of the 2010-2013 sovereign debt crisis is that banks and governments can be caught in a ‘doom loop’ in which financial instability and fiscal distress reinforce each other. Sovereigns might support the domestic financial sector at a large budgetary cost that undermines fiscal sustainability. As banks keep large amounts of domestic public debt in their portfolios, their exposure to sovereign risk undermines their balances (Broner et al., 2014). Financial stability can be compromised if the value of government securities on banks’ balance sheets falls, exposing banks to a reduction in the value of their assets, triggering collateral risk, capital losses, and counterparty risk. Shortfalls on the balance sheet can potentially destabilise the banking sector as a whole (Brunnermeier et al., 2016). While new institutional safeguards and monetary interventions by the ECB have mitigated these risks, the debate on fiscal policy and financial stability is not closed. Rising debt ratios are casting doubt on the fiscal capacity to provide economic stabilization. High public debt in the EU (and other advanced economies) combined with rising interest rates in an inflationary context, together with 3T spending, and the phasing out of QE poses challenges to fiscal policies and the financial system. A problematic issue is that the financial sector’s home bias, defined as the preference of domestic banks to hold sovereign debt issued by their own government, is still high.

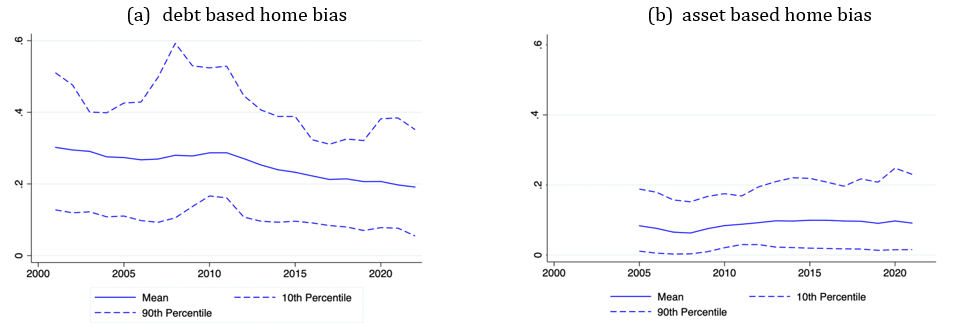

We construct two measures of home bias using IMF sovereign debt holdings data from 2001 to 2023 for all EU Member States using the database on sovereign debt holdings by Asonuma et al. (2015). The first measure – the debt-based home bias – represents the share of domestic public debt held by domestic banks relative to total public debt. This metric captures the extent to which governments rely on domestic banks for financing. The second measure – the asset-based home bias – calculates the proportion of sovereign bonds within total bank assets, reflecting the preference of domestic banks for holding sovereign debt compared to other financial assets.

A plot of the average home bias, and the first and last decile, overall show a modest decline in the debt-based home bias measure over time, while for the asset-based home bias, we observe a moderate increase (Figure 1). Furthermore, the data reveal significant variations in home bias across EU countries. Euro area Member States exhibit a declining debt-based home bias, largely due to European Central Bank interventions, whereas non-euro area countries display stable or increasing levels. The asset-based measure highlights that countries with well-developed financial systems maintain a lower share of sovereign debt within bank assets, except for a few cases where domestic financial conditions create incentives for banks to hold more government bonds. High levels of home bias in EU countries raises concerns on the use of fiscal policy for economic stabilization, while safeguarding financial stability.

Figure 1. Home bias in EU countries (mean and 10/ 90th percentile)

The effects of a higher home bias on fiscal sustainability are not straightforward, however. On the one hand, fiscal discipline might be weakened by a higher home bias. The easy placement of public debt mainly via the domestic banking system might not immediately raise concerns on public debt. In fact, well-developed financial systems allow governments to issue debt on favourable terms, usually with large domestic banks as the major market makers. An economic or financial crisis might eventually trigger a rise in the financing cost for governments, and if fiscal space is tight, might even trigger a sovereign debt crisis (Asonuma et al., 2015). Such a situation could then also require central bank intervention to take on the burden of bailing out banks and governments (Brunnermeier et al., 2016).

On the other hand, increased holdings of domestic sovereign bonds can also act as a disciplinary device if governments fear the consequences of a financial crisis on domestic macroeconomic stability (Coeurdacier and Rey, 2013; Gennaioli et al., 2018). This would be particularly a concern in less developed financial markets (Ebeke and Lu, 2015). Tighter constraints on fiscal policy might result in particular from the presence of foreign banks. As these banks render the banking sector more efficient, access to international markets reduces risk-taking and improves allocation of capital (Sengupta, 2007). If foreign banks transfer significant profits abroad, this can limit tax resources. Foreign banks might also be a more critical partner of the government for marketing public debt. However, foreign entry might could be destabilising for the host country’s banking sector through the transmission of cross-border shocks, and carry a potential fiscal cost. Finally, default on domestic public debt held by foreign banks comes at little political cost to the sovereign (Balteanu and Erce, 2018).

The banking sector in some EU Member states has an important share of state-owned banks. Government participation in the banking system potentially facilitates debt placement by the sovereign and could endanger fiscal sustainability (Becker and Ivashina, 2018). Nevertheless, public banks could impose more discipline if governments are concerned about their financial stability and the effects on their clients.

Empirical evidence on the role of the home bias on fiscal responses is limited. Variations over time and across EU countries provide an opportunity to assess whether the home bias modifies the consolidation response across of governments in different institutional and economic environments. We apply a novel method – smooth transition – on a panel of 27 EU Member States using the extension of the IMF database by Asonuma et al., 2015).

To examine the impact of home bias on fiscal policy, we test a standard fiscal rule à la Ghosh et al. (2013) in which the government sets the primary surplus in response to public debt. We employ a panel smooth transition regression model to capture the potentially non-linear effects of the home bias on this debt response. Unlike traditional linear models, this approach accounts for potential regime changes in fiscal consolidation and output stabilization responses according to the level of the home bias. By applying this methodology, the study identifies thresholds at which the home bias significantly alters fiscal responses by governments.

In addition, we control in the fiscal rule for characteristics of the financial system, in particular on the structure of the financial markets in terms of depth, access and efficiency of financial markets and institutions (using the IMF Financial Development Index), as well as the role of foreign and state-owned banks, using the recent Panizza (2024) database.

Our empirical results reveal that home bias has a substantial impact on fiscal sustainability. Three main findings stand out.

The first finding is that countries with high home bias do not necessarily experience weaker fiscal discipline, but allow automatic stabilizers to operate more freely, and adopt counter-cyclical fiscal policies, relying on financial market access to both manage debt and stabilize output fluctuations. A supplementary analysis testing the response to debt shocks shows that for higher levels of the home bias, short-term fiscal consolidations reverse after a few years. This suggests that while a home bias allows temporary fiscal flexibility, it also contributes to long-term debt accumulation.

The second finding is that euro area and non-euro area countries have a pronounced different fiscal behaviour. In the euro area, under a high home bias, fiscal policy substantially increases the debt sustainability response, while exhibiting more pronounced procyclical patterns and allowing for transitory deviations in spending without a correcting response, which is a typical finding for euro area countries (Larch et al., 2021; Gootjes and De Haan, 2022). By contrast, non-euro area countries tend to prioritize fiscal consolidation, due to limited financial market depth and external borrowing constraints, just as in other emerging markets. Fiscal policy becomes more powerful as a stabilisation tool when financial access to markets improves (Carrière-Swallow and Céspedes, 2013; Eichengreen et al., 2023).

The third finding is that the structure of the financial system matters. More liquid and efficient financial markets would allow governments to tap into bond markets more easily (enabling lower surpluses on average). In addition, the presence of foreign banks appears to support fiscal sustainability by diversifying debt placement. Finally, a higher share of state-owned banks reduces fiscal discipline and increases sovereign risk exposure.

The study provides new insights into the role of home bias in shaping fiscal policy within the EU. While institutional reforms and regulatory measures have reduced the risks associated with sovereign-bank linkages, home bias remains a persistent feature of EU financial systems. The results indicate that home bias can either support fiscal stabilization or create risks of fiscal slippage, depending on the financial structure and economic situation.

The implication for fiscal policy surveillance in the euro area is that greater financial integration in the EU could mitigate risks associated with home bias. Strengthening the Banking and Capital Markets Unions would allow governments to access more diversified financial markets, reducing reliance on domestic banking sectors for debt placement. Countries with high home bias may require stricter debt management frameworks to ensure long-term sustainability, while those with more open financial markets might benefit from greater fiscal flexibility.

Overall, the persistence of home bias underscores the need for continued reforms in the EU’s financial and fiscal architecture. Given historically high debt levels and the evolving economic transition, ensuring that fiscal policies remain sustainable will be crucial in preventing future sovereign-bank crises. The findings contribute to the broader debate on how financial development influences fiscal outcomes, emphasizing the need for policies that balance economic stabilization with responsible debt management.

Asonuma, M. T., Bakhache, M. S. A. and Hesse, M. H. (2015). Is Banks’ Home Bias Good or Bad for Public Debt Sustainability? IMF Working Papers 044/2015. International Monetary Fund.

Balteanu, I., and Erce, A. (2018). Linking bank crises and sovereign defaults: Evidence from emerging markets. IMF Economic Review 66: 617-664.

Broner, F., Erce, A., Martin, A. and Ventura, J. (2014). Sovereign debt markets in turbulent times: Creditor discrimination and crowding-out effects. Journal of Monetary Economics 61: 114-142.

Brunnermeier, M. K., Garicano, L., Lane, P. R., Pagano, M., Reis, R., Santos, T. and Vayanos, D. (2016). The sovereign-bank diabolic loop and ESBies. American Economic Review 106(5): 508-512.

Carrière-Swallow, Y. and Céspedes, L. F. (2013). The impact of uncertainty shocks in emerging economies. Journal of International Economics 90(2): 316-325.

Coeurdacier, N. and Rey, H. (2013). Home bias in open economy financial macroeconomics. Journal of Economic Literature 51(1): 63-115.

Ebeke, C. and Lu, Y. (2015). Emerging market local currency bond yields and foreign holdings–A fortune or misfortune?. Journal of International Money and Finance 59: 203-219.

Eichengreen, B., Hausmann, R. and Panizza, U. (2023). Yet it endures: the persistence of original sin. Open Economies Review 34(1): 1-42.

Gennaioli, N., Martin, A. and Rossi, S. (2018). Banks, government bonds, and default: What do the data say?. Journal of Monetary Economics 98: 98-113.

Ghosh, A. R., Kim, J. I., Mendoza, E. G., Ostry, J. D. and Qureshi, M. S. (2013). Fiscal fatigue, fiscal space and debt sustainability in advanced economies. The Economic Journal 123(566): F4-F30.

Gootjes, B. and de Haan, J. (2022). Procyclicality of fiscal policy in European Union countries. Journal of International Money and Finance 120: 102276.

Larch, M., Orseau, E. and Van Der Wielen, W. (2021). Do EU fiscal rules support or hinder counter-cyclical fiscal policy?. Journal of International Money and Finance 112: 102328.

Panizza, U. (2024). Bank ownership around the world. Journal of Banking and Finance, 166, 107255.

Sengupta, R. (2007). Foreign entry and bank competition. Journal of Financial Economics 84(2): 502-528.