Disclaimer2

We see the Recovery Fund as a gamechanger for Europe and the euro. But many investors are not yet convinced. We set out some of the pushback we have gotten, and explain why we still think the scepticism is overdone.

We have argued that the EU Recovery Fund is a potential game changer for the periphery, and thus for the overall stability of the euro area. But that is not to say that the Recovery Fund will necessarily deliver as intended; financial and economic stability is always a work in progress. In this note, we share some of the more sceptical questions and reactions we have heard from investors, as well as possible responses. Notable doubts include:

Not everyone is convinced that the fund is a game changer for the periphery countries and for European stability more generally. In this note, we comment on some of the more sceptical reactions we have heard from investors.

It is true that the Recovery Fund does not mutualize past debt and, for now, proposes only modest forms of common EU taxation to service debt. Worse, the Recovery Fund is in principle a one-time response to a once-in-a-lifetime shock, limited in scope, purpose, and duration – i.e., not a permanent instrument of common fiscal policy. As such, comparisons to Alexander Hamilton’s 1790 reforms to assume state debts and establish a US federal budget and debt market seem hyperbolic.

But all reforms since the inception of the EU have taken place incrementally. The Recovery Fund is a very large step in the direction of establishing a union level fiscal policy, and even if it does not achieve Hamiltonian perfection, it is of signal importance. Four observations in this regard:

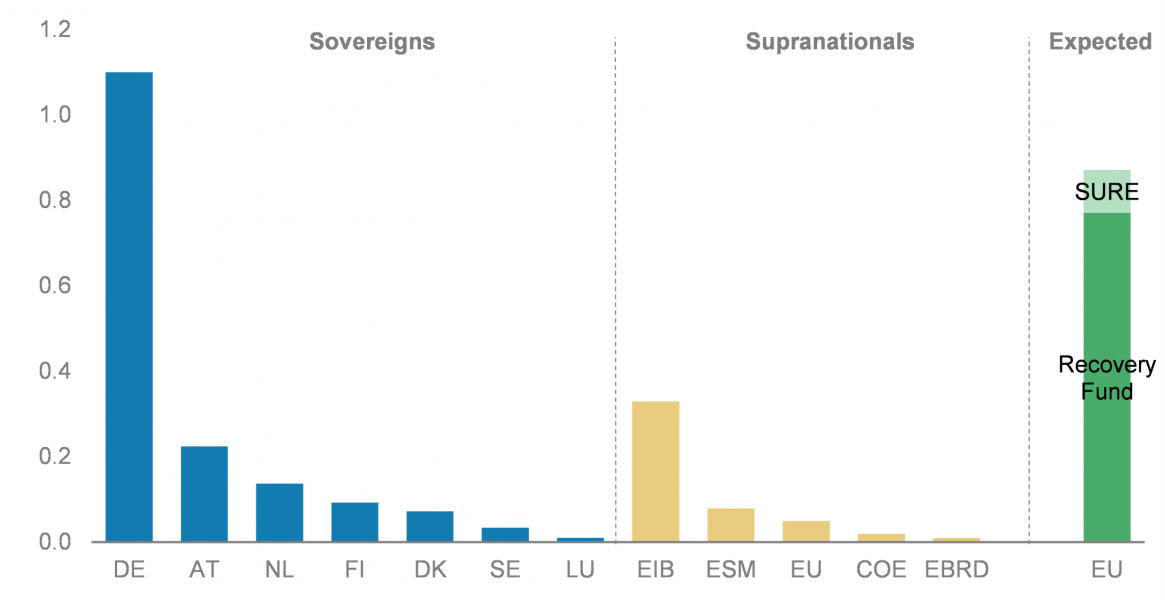

Highly rated sovereign bonds in Europe

Note: Includes outstanding issuance by European sovereigns and supranationals that are rated AAA by at least one agency, or AA+ by at least two agencies. Agencies considered are S&P, Fitch and Moody’s. Source: Bloomberg, Morgan Stanley Research

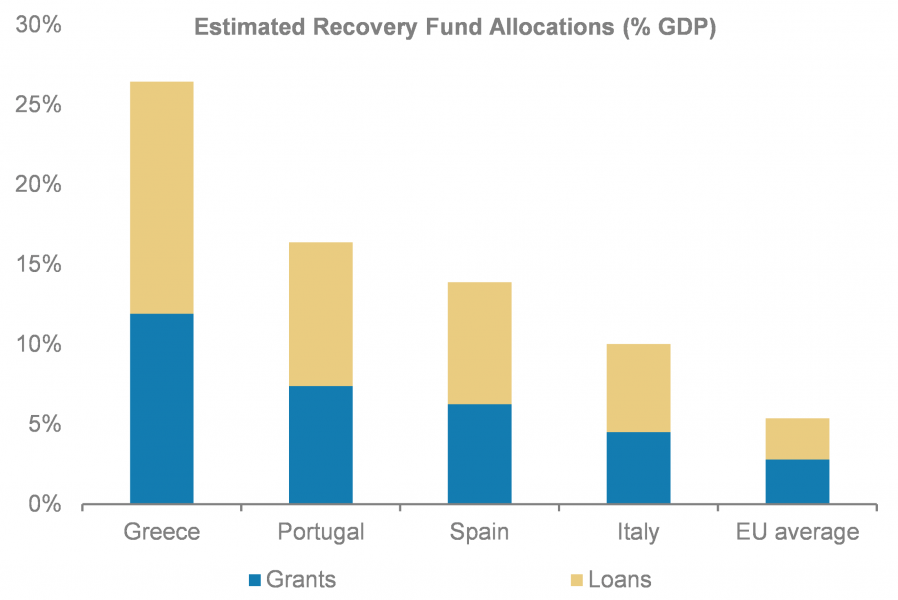

Periphery allocations as share of GDP

Source: European Commission, Morgan Stanley Research

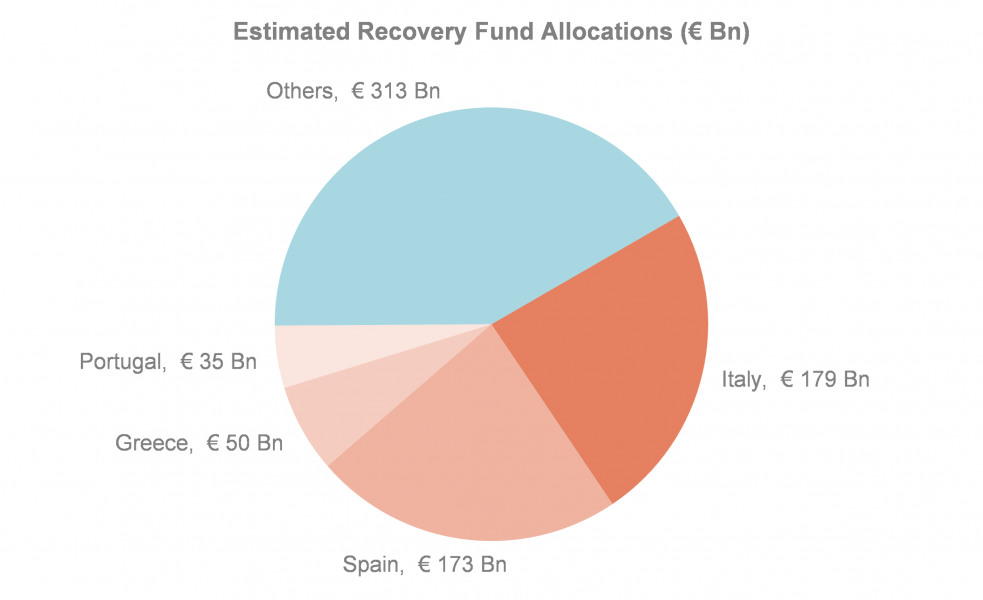

Periphery allocations as share of total funds

Source: European Commission, Morgan Stanley Research

The Recovery Fund effectively targets the hardest hit countries in Europe’s southern periphery – Greece, Italy, Spain, and Portugal. Relative to the size of those economies, the amounts being made available in grants and lowinterest/long-term loans are substantial. Fiscal stimulus ranging from over 2% to around 7% of GDP per year for four years is assuredly a big deal for the growth and sustainability prospects of those countries.

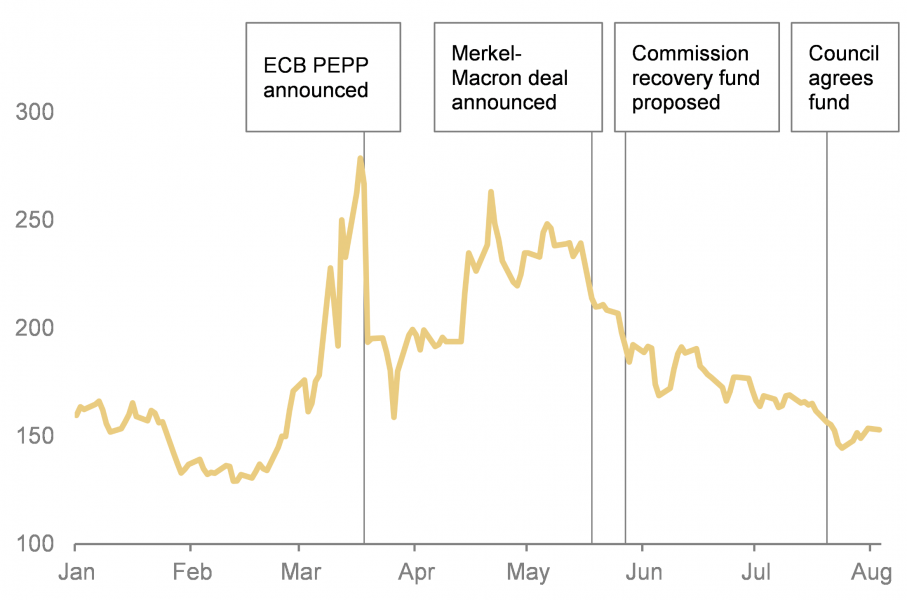

Markets certainly have taken note of the Recovery Fund. Ever since the word got out of the core political compromise underlying it – the Merkel-Macron proposal in mid-May – risk spreads on periphery debt have fallen back substantially; Italy’s spread has fallen by over 100 bps since that time, and is now below the level at end-2019.

Italy 10Y yield spread vs Germany

Source: Bloomberg, Morgan Stanley Research

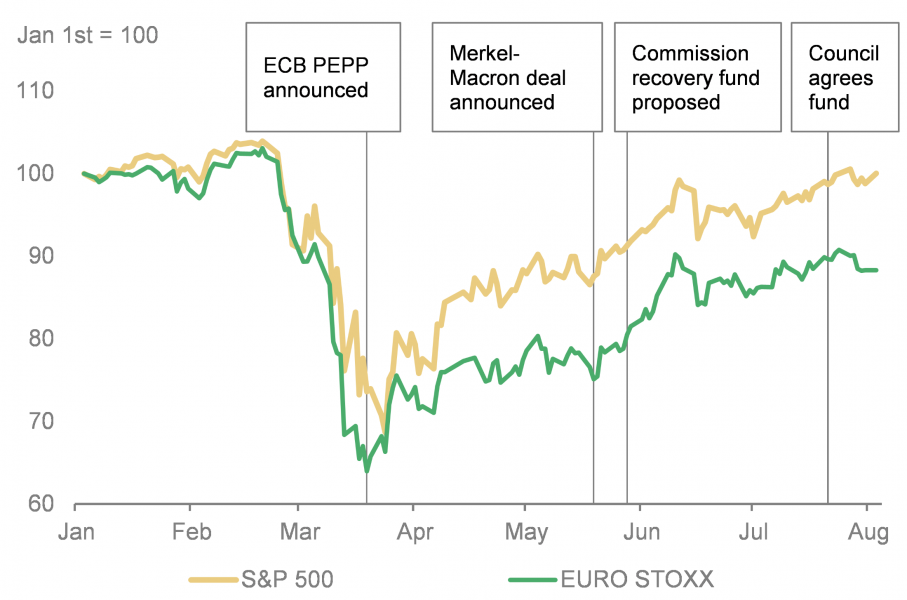

That said, the sceptics might still ask why all this has not translated into broader strength in euro assets? Fair enough. Although the euro has appreciated, the performance of Eurostoxx pretty much tracks the S&P500. However, as the Nobel-prize winning economist Robert Shiller has argued, it may take time for the market to absorb new information and for a new narrative to take hold, especially in the context of a pandemic.

European and US stock market performance YTD

Source: Bloomberg, Morgan Stanley Research

The EU Council did introduce political oversight and review of countries’ spending plans, which is understandable given the unprecedented scale of cross-border transfers. But formal rules were also put in place to avoid undue delays. Two points:

The Recovery Fund will only start operating in 2021, and while 70 percent of the funds are expected to be committed during 2021-22, actual disbursements will be made later, likely peaking during 2022-23. So, it is certainly correct to say that the main impact of the Recovery Fund will not be felt for some time. On the other hand:

That said, we do agree that more thought needs to go into Recovery Fund spending. As we have argued elsewhere, in the time horizon of the Recovery Fund (2022-24), it would make more sense to target spending to unconstrained sectors (e.g., green and digital, where supply can readily respond to demand) than to constrained sectors (e.g., tourism and transportation, where public spending is unlikely to provoke strong supply and demand responses).

In targeting the hardest hit economies, the Recovery Fund also happens to be targeting the most fiscally constrained ones – Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain. For sure the grants element of the Recovery Fund is additional spending because it does not add to national governments’ debt and does not have to be paid back. However, there is no way of proving a counterfactual.

The reality is that there are no fiscal adjustment paths agreed or even specified by either the Commission or any member state with and without the Recovery Fund to assess the additionality argument. The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) has been rightly suspended to allow governments to respond to the crisis as needed. The SGP will be reinstated at some stage but not necessarily in its pre-crisis form. Indeed, a review of SGP was already under way before the crisis hit.

Ultimately, the growth path out of the crisis will be a more important determinant of debt sustainability than any fiscal adjustment path. In that sense, the Recovery Fund, with its focus on spending in the hardest hit countries for the next few years, can provide additional spending and a transition to the post crisis SGP.

This is a sophisticated political economy critique. But whether it is a priori correct is not obvious. Without taking too pointed a stand, we would note the following:

We acknowledge the contribution of Camille White to this report.

This article is based on research published for Morgan Stanley Research on August 6, 2020. It is not an offer to buy or sell any security/instruments or to participate in a trading strategy. For important current disclosures that pertain to Morgan Stanley, please refer to Morgan Stanley’s disclosure website: https://www.morganstanley.com/eqr/disclosures/webapp/generalresearch . Copyright 2020 Morgan Stanley.