We first provide an overview of the financial integration and cooperation in the Nordic-Baltic region. At the EU-level, integrating the capital markets in Europe as a whole is a priority. A notable part of this process is the European banking union. We therefore also discuss two issues regarding Sweden’s participation in the banking union. First, the trade-offs of supranational supervision in the Nordic-Baltic region vis-à-vis the EU. Second, the risk faced by those EU-members that are outside of both the banking union and the currency union of becoming marginalised in negotiations at the EU-level versus the risk – if joining only the banking union – of being marginalised in negotiations within the banking union.

“Global banking institutions are global in life, but national in deaths”

Mervyn King2

The limits of monetary policy are sometimes discussed based on the well-known monetary trilemma of an open economy under free capital mobility across borders, see Mundell (1963). The trilemma highlights the difficulty of combining (1) independent monetary policy, (2) free capital mobility, and (3) a fixed exchange rate. Two, but not all three, of the objectives can be achieved at the same time. If monetary policy is independent and, at the same time, capital mobility is free, the exchange rate cannot be fixed.3

A perhaps less known trilemma is that of financial stability policy, which emphasises the limits of national financial policy.4 According to this trilemma (1) national financial policy, (2) cross-border financial integration, and (3) financial stability are incompatible. As is the case with the monetary trilemma, only two of these three objectives can be achieved at the same time. For example, if the objectives are financial integration across borders and a stable financial system, financial policy cannot be national.

The financial trilemma is illustrated in Figure 1. In essence, when financial integration increases in a region, the incentives among national supervisors to act in a way that preserves financial stability in the region as a whole decreases. If the benefits of stability oriented policies spread to the region as a whole, the willingness of national supervisors to bear the cost of these polices decline, see Schoenmaker (2011). Hence, there is a positive externality – that is not fully internalised by national supervisors – of stability oriented policies at the national level.5 To increase financial integration and at the same time maintain financial stability at the regional level, greater cooperation among national supervisors is necessary to internalise the externality. The trilemma is best viewed as an illustrative example of the benefits of supranational supervision. When evaluating these benefits in practice factors that are not included in the trilemma also need to be accounted for.

In this short article, we take the financial trilemma as a starting point to discuss financial integration and cooperation in the Nordic-Baltic region vis-à-vis the EU from a Swedish perspective. The discussion focuses on the potential participation of Sweden in the European banking union, which is an issue that currently is in the public eye. The Swedish government has held a public inquiry to evaluate the effects if Sweden were to join the banking union, see Swedish Government Inquiries (2019). In addition, the Riksbank has recently responded to the inquiry, see Sveriges Riksbank (2020a).

The article proceeds as follows. In the next section, we discuss financial integration and cooperation in the Nordic-Baltic region. The following section briefly reviews the banking union. The final two sections discuss two issues regarding Sweden’s potential participation in the banking union. The first of these two sections discusses the benefits and costs of supranational supervision in the Nordic-Baltic region vis-à-vis the EU, while the second section discusses the risk for EU-members that are outside of both the banking union and the currency union of becoming marginalised in negotiations at the EU-level versus the risk – if joining only the banking union – of being marginalised in negotiations within the banking union.

Figure 1. The financial trilemma

Source: Authors’ illustration.

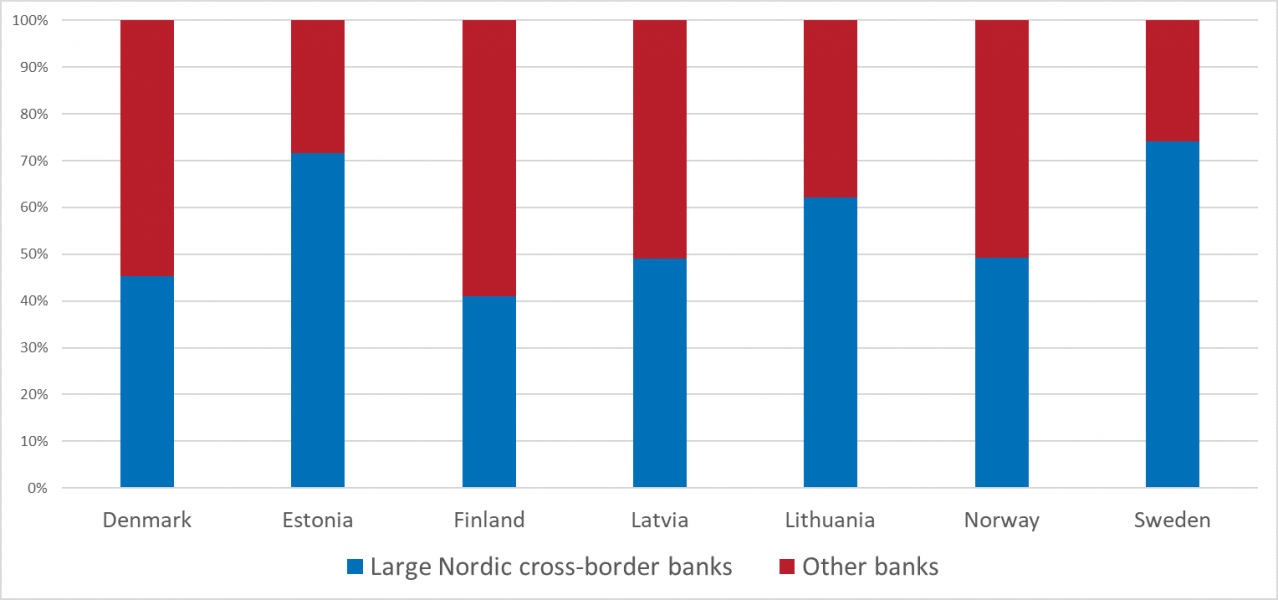

The Nordic-Baltic region has a high degree of financial integration. Figure 2 shows the share of lending of six large regional banks. These banks account for between 40 to 75 percent of the share of lending to the public in the region. The fact that the region has been dominated by a handful of large cross-border banks has created incentives for cooperation between financial stability authorities in the region. This cooperation was strengthened during the global financial crisis that broke out in 2008. Apart from a number of national measures aimed at boosting the functioning of local financial markets, regional cooperation was key to promoting an effective crisis management. For example, in May 2008, the central banks of Denmark, Norway and Sweden entered into swap agreements with the central bank of Iceland. Later in 2008 the Riksbank and Nationalbanken agreed on swap arrangements with the Latvian Central Bank as a bridge to the funding from the IMF. Furthermore, a swap agreement was also concluded between the Riksbank and Eesti Pank in 2009.6 This cooperation laid the foundation for deepened cooperation in the Nordic-Baltic region as the GFC subsided. Several regional groups have been set up for this purpose, not only between central banks but between supervisors, resolution authorities and Ministries of Finance.

Figure 2. Share of lending to the public

Note: Large Nordic cross-border banks include: Danske bank, DNB, Nordea, Handelsbanken, SEB and Swedbank.

Sources: Bank reports and Sveriges Riksbank (2018).

Regional groups of cooperation

An important forum of cooperation in the macroprudential area is the Nordic-Baltic Macroprudential Forum (NBMF). This forum was created in 2011 and brings together central banks and supervisory authorities at senior level in twice-yearly meetings.7 The task of the NBMF is to discuss risks to financial stability in the region and the implementation of macroprudential policies to counter such risks. The Forum also discusses topical issues – with relevance from a macroprudential perspective – that are discussed in other international forums.

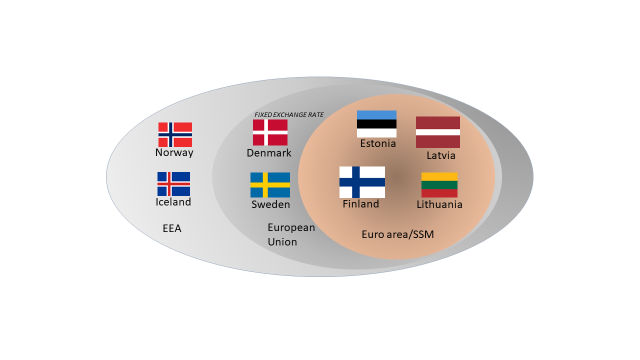

While financial sector integration is strong in the region, the countries are not as homogenous as might be the general perception. As is shown in Figure 3, all countries are members of the EU except Iceland and Norway. Finland and the three Baltic states have adopted the euro and are thus members of the banking union. Denmark is pursuing a fixed exchange rate while Sweden has a floating exchange rate.

Figure 3. Different characteristics of the Nordic-Baltic countries

Source: Authors’ illustration

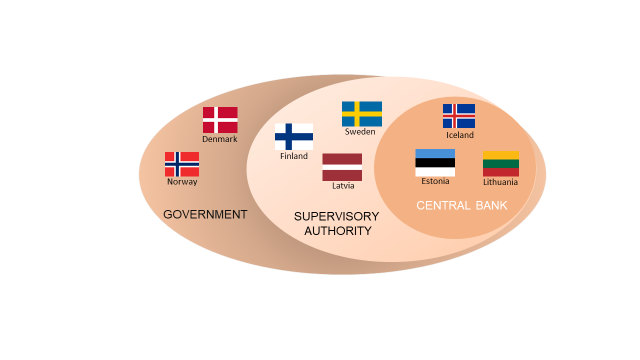

There are also differences between the countries when it comes to whom has been given the role as designated macroprudential authority, see Figure 4. While both Norway and Denmark have put their Ministries of Finance in charge of macroprudential policy, in Finland, Latvia and Sweden, the same role is performed by the supervisory authorities. And finally, in Estonia, Iceland and Lithuania, the central bank is the designated authority.

Figure 4. Designated macroprudential authority in the Nordic-Baltic countries

Source: Authors’ illustration

Prior to the global financial crisis in 2008-2009, the concept of macroprudential policy as such did not exist in the Nordic and the Baltic countries. However, the Baltic countries introduced certain measures prior to the financial crisis to dampen growth in mortgage lending, but the high penetration of foreign branches reduced the effectiveness of these policy measures.8 Setting regulatory standards higher than the regulatory minimum was from time to time seen as threatening the competitiveness of domestic institutions in a number of countries when market shares of foreign branches were growing rapidly. The lack of dedicated measures to safeguard financial stability also sparked a discussion of the possible use of monetary policy to “lean against the wind”.

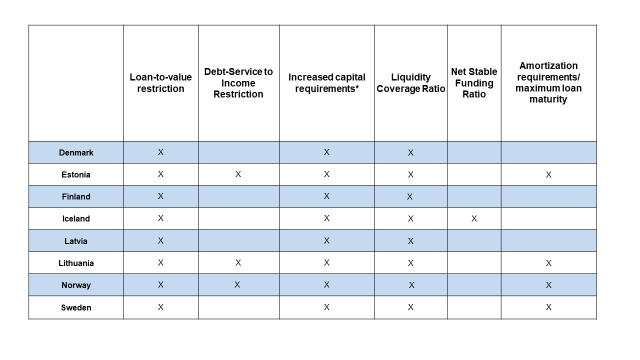

Since the creation of the NBMF in 2011, a number of measures of macroprudential nature have been taken in the region. Table 1 provides an overview of the implementation of macroprudential measures in the Nordic-Baltic countries. The measures focus on capital and liquidity requirements. Borrower-based measures, such as Loan-to-value restrictions, are also implemented across the region. Tools targeting mortgage lending, such as debt-to-income or debt-service-to-income measures, are also prevalent, but to a lesser degree.

Table 1. Overview of the implementation of macroprudential measures in the Nordic-Baltic countries

* Includes Counter-Cyclical Capital Buffer, Systemic Risk Buffer, Capital Conservation Buffer, Additional capital requirements for Systemically Important Institutions, Sector Specific Risk Weight Floor, Risk Weight Floor.

Source: Nordic-Baltic Macroprudential Forum (NBMF), 2019.

Main lessons and challenges

The NBMF has proven to be an important informal forum for discussion of financial stability risks and macroprudential measures. It has enabled central banks and supervisors to meet regularly and discuss issues of mutual interest. It has promoted an increased understanding of cross-border issues and more in-depth analysis of the detailed implementation of the various macroprudential measures. As it provides a regional perspective, it supplements European groups such as the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB).

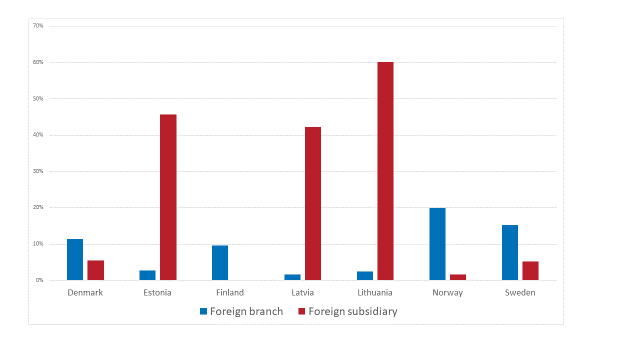

In order for macroprudential policy to be effective in an environment with a high degree of cross-border banking and banks operating in the form of branches, the issue of so called reciprocation of macroprudential policy becomes important. To illustrate, if a country is hosting a number of foreign branches and sees the need to increase capital requirements for a particular exposure, the national designated macroprudential authority does not have jurisdiction over the exposures in the foreign branches. Hence, it can only ask the home supervisor of the branch to reciprocate the measure, i.e., to also increase capital requirement in its own jurisdiction for exposures taken by the branch. In the absence of such reciprocation, the measure can become less effective. Figure 5 shows the relative importance of branches and subsidiaries in the region. In many countries foreign branches are important, making the reciprocation of macroprudential policy necessary to ensure the effectiveness of the measures taken. In view of the close cooperation between the Nordic-Baltic authorities, not least in the context of the NBMF, reciprocation has worked well.

Figure 5. The importance of branches and subsidiaries in the region

Note: Percent of total assets in local currency of large Nordic banks. End 2018 data.

Sources: Bank reports and Sveriges Riksbank.

Close cooperation on crisis preparedness

The Nordic-Baltic countries have also established close cooperation in the area of crisis management. In 2010, the Nordic-Baltic Stability Group (NBSG) was established between Ministries of Finance, Central Banks and Supervisory and Resolution authorities. The NBSG was the first stability group in Europe. The main focus of the NBSG has been to discuss and exchange information on a regular basis on important issues related to financial stability concerns in the region. Another main task has been to prepare and hold regular financial crisis simulation exercises.

In January 2019, a major financial crisis management exercise was carried out in the Nordic-Baltic region. A working group, under the chairmanship of the Riksbank, had prepared the simulation, which included around 300 persons from 31 different authorities in the region, as well as relevant European organizations. The two-day exercise simulated the need for liquidity provision as well as resolution of two fictitious regional banks.

The exercise provided a wealth of experiences that the authorities continue to discuss, including a number of challenges. One such challenge was the communication between home and host authorities and information sharing within the supervisory and resolution colleges of the fictitious banks involved in the simulation. In the scenario set-up, the home authorities of both banks were outside of the Euro Area and hence the banking union, while both banks had subsidiaries in countries within the banking union. This was the first time the European Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive was tested in a truly cross-border setting, involving authorities both within the banking union and authorities outside of it.

The initiative to form a banking union in Europe was announced in 2012, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis 2008–2009 and the following European sovereign debt crisis 2010–2012.9 As the debt crisis in Europe deepened, the financial markets started to lose confidence in the currency union and begun to speculate of a break-up of the euro area. A break-up would have led to severe negative consequences for the economic prospects in Europe. The formation of the banking union, together with a number of rescue packages, helped restoring confidence in the euro.

The origin of the banking union was thus a response to the European debt crisis, but the union is also an essential complement to other financial policies and regulations in Europe. It reduces market fragmentation by further harmonising the rules of the financial sector and deepening the European market for financial services. This helps creating a so called level-playing field for banks, which encourages higher competition and efficiency in the banking sector.10

The banking union is an “institutional framework” that organises supervision and crisis management of banks. At the moment it is based on two pillars: The Single Supervisory Mechanism and the Single Resolution Mechanism, which also includes the Single Resolution Fund. A potential third pillar, the European Deposit Insurance Scheme, is under discussion but remains to be agreed upon. Members of the euro area are obliged to participate in the banking union, but non-members, i.e., Sweden and a number of other countries in the EU, can participate under certain conditions.11

Free capital mobility is a prerequisite for free trade, which in particular for small economies is a key factor for economic growth.12 Moreover, free capital mobility encourages banks to open up subsidiaries and branches in other countries and regions contributing to lower investment costs.13 Furthermore, it gives investors better opportunities to diversify risk, which, for example, help pension funds to provide a more secure retirement income.

However, free movement of capital is not without challenges. Large capital inflows can fuel macroeconomic and financial imbalances that later unwind as financial crises. A strong national financial system with adequate financial policies and regulations is the first line of defense against financial crises. This may not be enough, though, as the financial trilemma suggests. When movement of capital is free and cross-border banking activity is high, coordination and cooperation between national supervisors is also needed, i.e., supranational supervision of banks.

Supranational supervision is thus a central feature in preserving financial stability when cross-border banking activity is high, but it can be associated with economic costs. Beck and Wagner (2016) argue that the heterogeneity of countries make supranational supervision costly. They look at heterogeneity along three dimensions: (1) the banking and the market structure, (2) the political, legal and regulatory structures, and (3) the societal risk preferences. There is therefore a trade-off between more supranational supervision due to cross-border externalities and less due to heterogeneity across countries. In addition, Beck and Wagner show that even when a higher degree of supranational supervision is optimal, it may only happen if both regions benefit.

Beck et al. (2018) and Beck (2019) construct an index that is intended to capture the cross-border externalities and another one that captures the heterogeneity across countries.14 Both indices are normalised to be between zero and one, to make them comparable with each other. A high value indicates high levels of externalities as well as heterogeneity. Hence, the higher the externality index and the lower the heterogeneity index, the more supranational supervision is called for.

The externality index of the Swedish banking sector within the Nordic countries is 0.38, while it is 0.31 within the Nordic-Baltic region and 0.25 within the European Union. The higher externality within the Nordic and Nordic-Baltic regions is mainly driven by the externality from the financial trilemma and not by the other externalities included in the index. The heterogeneity index shows the opposite ranking: within the Nordic countries the index is 0.30, within the Nordic-Baltic region 0.38, and within the European Union 0.48. The indices thus suggest relatively strong externalities and low heterogeneities across the Nordic-Baltic region. This is likely one of the reasons why financial cooperation across this region is successful and has been contributing to strengthening financial stability in Sweden and the region as a whole.

Taken at face value the indices suggest less support for the idea that Sweden should join the banking union compared to Nordic-Baltic cooperation. However, the quantitative difference in the indices for the Nordic-Baltic region and the EU should not be exaggerated. The difference is also likely to diminish over time as the financial integration in Europe moves forward. It is also already the case that the subsidiaries of two major Swedish banks in the Baltic region are under the supervision of the ECB, since they have market-dominant positions in this region. From an individual bank perspective, being supervised by the ECB can be preferred, as the move of Nordea from Sweden to Finland suggests.

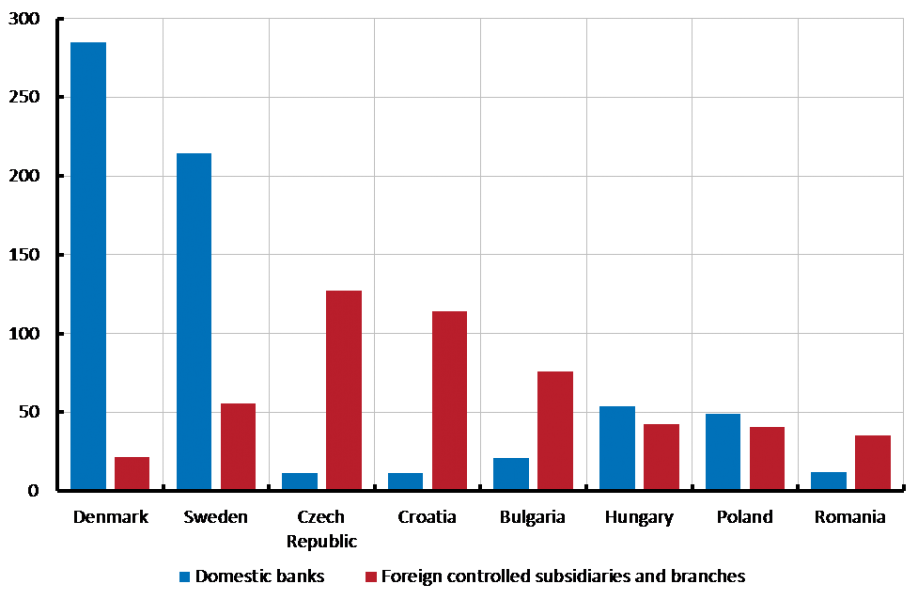

EU-members that are outside of both the currency union and the banking union, such as Sweden, face a risk of becoming marginalised in negotiations, even more so since the UK have left the EU. From a financial cooperation perspective, Sweden has relatively little in common with the other non-euro countries, Denmark being the exception. Sweden is the home country of large banking groups, while other non-euro area countries – Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Romania – are primarily host countries of foreign banks, see Figure 6. This can potentially lead to different interests in negotiations. Sweden’s international influence has also been declining over the years, see Swedish Government Inquiries (2019) for a discussion. This trend will likely continue, but participating in the banking union could potentially mitigate the trend.

In normal times, participation in the banking union will most likely not affect the regulation and crisis management of the Swedish banks in any major way. There are pros and cons. On one hand, Swedish supervisors have greater flexibility to design national requirements if Sweden stays out, although this room for manoeuvre is likely to shrink over time. On the other hand, participation would give access to the large supervision and resolution resources of the banking union – on top of national resources.

Participation in the decision making process within the banking union is not the same for the euro and non-euro countries.15 Non-euro countries do not have voting rights in the Governing Council of the ECB. Hence, there is, in principle, a risk for non-euro countries of being marginalised in negotiations within the banking union. This is discussed in Sveriges Riksbank (2020a). However, there are two safeguard mechanisms that have been created to compensate non-euro countries for the lack of voting right in the ECB Governing Council. First, if a supervisory decision goes against Sweden, we would have the right to explain that we do not intend to comply with the decision, which could have the consequence that the ECB decides to expel Sweden from the banking union. Second, there is a possibility for a non-euro country to withdraw from the banking union at any point after three years’ participation (this does not have to be linked to a supervisory decision against one of the country’s banks).

Figure 6. Size of the banking sectors in non-euro area countries, 2019 Q3

Note: Percent of GDP.

Source: ECB.

The integration of European countries is an ongoing process involving many different institutions and markets. At the core of this process is the European Union and its institutions. From a financial perspective, integrating the capital markets in Europe and creating a level-playing field is a priority. This process is not straightforward, though, and long-term planning is often difficult. New institutions and structures do in many cases not emerge until they are deemed to produce value added, as, for example, was the case with the creation of the banking union.

The Swedish government has recently held a public inquiry where an in-depth analysis of different issues regarding a Swedish participation in the European banking union has been presented, see Swedish Government Inquiries (2019) and the response of Sveriges Riksbank (2020a). See also Beck (2019) for a discussion of the main issues from a Swedish perspective. We have discussed two of the specific issues in this article – the trade-off of supranational supervision and the risk of marginalisation in the decision process for countries outside of the euro area. We have also given an overview of the financial integration and cooperation in the Nordic-Baltic region. Leaving the many specific issues aside, the broader picture suggests that an extension of financial integration and cooperation from the Nordic-Baltic region to the EU-level is a natural next step for Sweden. The economic benefits of more cross-border banking activities across Europe are potentially large and the banking union is an important step in this direction. When evaluating the benefits of more cross-border banking, the benefits should not only be assessed through the lens of one specific country. Such an analysis does not account for the positive externalities of a greater market with better competition and increased efficiency that will benefit all members. Such benefits are potentially large.

Beck, Thorsten (2019), “Better In or Better Out: Weighing Sweden’s Options Vis-à-vis the Banking Union”, Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies, SIEPS 2019:2.

Beck, Thorsten and Wolf Wagner (2016), “Supranational Supervision: How Much and For Whom?”, International Journal of Central Banking 12, pp. 221–268.

Beck, Thorsten, Consuelo Silva-Buston, and Wolf Wagner (2018), “The Economics of Supranational Bank Supervision”, CEPR Discussion Paper no. 12764.

Ehrenpil, Markus and Mattias Hector (2017), “Banking Union – What is it?”, Sveriges Riksbank Economic Commentaries, 2017:5.

Farelius, David and Jill Billborn (2016) “Macroprudential policy in the Nordic-Baltic countries”, Sveriges Riksbank Economic Review, 2016:1.

Ingves, Stefan (2017), “Monetary policy challenges – weighing today against tomorrow”, Speech at Swedish Economics Association, 16 May 2017.

Mundell, Robert (1963), “Capital Mobility and Stabilization Policy under Fixed and Flexible Exchange Rates,” Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science 29, pp. 475–485.

RCG Europe Working Group (2016), “Nordic experience of cooperation on cross-border regulation and crisis resolution”, Report from RCG Europe Working Group, 2016.

Rey, Hélène (2015), “Dilemma not trilemma: the global financial cycle and monetary policy independence”, NBER Working Paper No. 21162.

Schoenmaker, Dirk (2011), “The financial trilemma”, Economics Letters 111, pp. 57–59.

Sveriges Riksbank (2020a), “Consultation response: Sweden and the banking union (SOU 2019:52)”, Sveriges Riksbank.

Sveriges Riksbank (2020b), “The Riksbank’s measures during the global financial crisis 2007–2010”, Riksbank Study, February 2020.

Swedish Government Inquiries (2019), “Sweden and the banking union”, English summary of the inquiry Sverige och bankunionen SOU 2019:52.

We thank Susanna Engdahl and Mattias Hector for valuable comments and suggestions. The opinions expressed in this article are our own and cannot be regarded as an expression of the Riksbank’s view.

Quote from “The Turner Review: A regulatory response to the global banking crisis”, March 2009.

Recent experiences show that national monetary policy with free capital movements can be difficult to achieve even with a flexible exchange rate, i.e., the monetary trilemma could be a dilemma, see for example, Rey (2015) and Ingves (2017).

By national financial policy we mean micro- and macroprudential policy and other financial regulations that are decided upon nationally without coordinating with out-of-the-country supervisors.

It can also be the case that a country that benefits from stability oriented policies in neighbouring countries may be tempted to exploit “imported” stability to pursue more expansionary, potentially destabilising, financial policies.

For further reading on the measures that were taken during the GFC, see Sveriges Riksbank (2020b).

See Farelius and Billborn (2016) for a discussion.

See RCG Europe Working Group (2016).

The banking union is supposed to be supplemented by a capital markets union. This is not a union in the same sense as the banking union, where you can chose to become a member, but an EU-wide initiative to increase cross-border financial operations in Europe and to increase the share of financing in financial markets relative to bank financing. There are also voices suggesting a fiscal union with a common budget.

An objective of the banking union is to strengthen financial stability in the euro area and in the EU as a whole, i.e., to ensure that banks are stable and can withstand future financial crises, see Ehrenpil and Hector (2017) for a discussion of the banking union’s purposes and functions.

See Sveriges Riksbank (2020a).

Free movement of labour is also important but is not the topic of this study.

The three largest banks in Sweden have subsidiaries and branches in Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Finland, Germany, Netherlands, and Poland in the EU and, as already discussed, Swedish banks have particularly strong linkages to the Nordic-Baltic region.

The externality index also includes three other externalities that advocate supranational supervision, i.e, market linkages, regulatory arbitrage and currency unions.

The efficiency of resolution cases and the risk a politicised crisis management are other key issues in a financial crisis, see Sveriges Riksbank (2020a) for a discussion of these issues.