Attempts to launch a capital market union in the EU so far have failed. This may have depended on the overambition of trying to build an integrated capital market from a greenfield while banking, which dominates continental finance, is itself not yet integrated. This paper argues for jumpstarting banking integration first, as a complement and prerequisite to build an integrated capital market as well. Suggestions on how this can be made are offered, summarizing a proposal made in a recent paper submitted to the European Parliament.

In spite of the EU Single Market program in the 1990s, the euro in 1999 and the single ECB banking supervision in 2014, the integration of the eurozone financial sector is still a goal to be achieved; European finance remains a loosely connected collection of national components. This paper offers some reflections on this failure and suggests possible ways forward. The European elections and the formation of a new Commission in 2024 offer the opportunity of a policy reset. The Union’s political center of gravity is shifting, with consequences that are still unclear. Wherever this may lead us, a strong integrated financial sector remains a central goal of the Union, a necessary ingredient of the thriving and globally competitive economy Europe needs as it moves further into the 21st century. This goal transcends politics, or at least it should.

In recent years, the odds to make progress on this front have been placed on a Capital Markets Union (CMU). So far, this project has not delivered. This paper suggests that more attention should be given to the integration of banking markets. Banking integration is not an alternative to capital markets integration, but a complement. Actually, it is probably a prerequisite, given the dominant role banks play in continental European finance. Eurozone banking markets are no more “united” today than they were a decade ago, in spite of the banking “union” having celebrated its tenth anniversary. Promoting progress toward banking integration means not only abiding to the commonsense principle “first things first”, but also giving CMU a better chance of success.

An insufficiently appreciated feature of the CMU plan is that it combines two goals in one: strengthening non-bank finance and financial integration. The two goals are not the same and it is not clear that a single set of policies can deliver both at the same time. In its goal, CMU lacks a clear focus. One consequence is that it attracts opposition from multiple quarters: from banks seeing capital markets as competitors; from national governments and regulators dreading the loss of control; and from national financial establishments which are likely to lose, in a supranational environment, the comfortable relations they enjoy nationally. All powerful incumbents, all the more if they join forces against the whole idea.

This paper starts by summarizing in section 2 the recent steps taken by EU Commission on CMU. It then revisits in section 3 some recent research on market-based and bank-based finance. The newest contributions to that literature tend to downplay the alternative between the two, seeing them as complements rather than alternatives. Merits and drawbacks, strong and weak points, depend on multiple factors – legal traditions, cultures, preferences. Starting conditions matter as well, because financial development is a path-dependent process. Section 4 presents some data on the capital market activities of eurozone banks. Two findings here. First, such activities tend to be highly concentrated: a small number of banking groups account for most of them. Second, those same banks, which are large by European standards but small globally, are also those that are most active across national frontiers. This evidence supports the idea that progress towards financial integration can be made by facilitating further cross-border reach of these banks. Finally, drawing on another recent paper, section 5 summarizes a set of regulatory changes that may help in this direction.

In 2015, the European Commission published its first “Action Plan on Building a Capital Market Union” (EU Commission, 2015); a strategy to broaden the funding options of European firms giving a stronger role to capital markets. Leveraging on the Union’s single market and single currency, the intent was to create deep, liquid and competitive area-wide markets serving principally the needs of the corporate sector, with particular focus on equity financing to innovative SMEs start-ups. The reference model was the United States, whose highly diversified, efficient and integrated market-oriented financial sector was seen as a key factor in that country’s superior economic performance.

The CMU Plan coexisted at the time with two other initiatives, the Juncker Plan and the banking union – the latter especially prominent on the wake of the successful start of the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM). The Juncker Plan, mobilizing over 300 bn euros of investment in key sectors over the 2015-2018 period, would be facilitated by broader capital markets. The successful establishment of the SSM, completed in just two years (2012-2014), contributed to a wave of optimism on the Union’s institution-building potential which encouraged the conception of the CMU as well.

Five years later, it was clear that in spite of some parts of the Plan having been initiated or even completed, the envisaged strengthening of Europe’s capital markets was not happening. Eurofi, a European think tank for financial services, wrote in 2020: “European capital markets remain under-developed compared to other developed regions, in terms of size relative to GDP and did not grow significantly over the last few years” (Eurofi, 2024; data on CMU progress can be found in AFME, 2020). To complicate matters, in 2020 Europe was in the midst of a deadly pandemic, an economic recession and re-nationalization of financial markets. Not discouraged, the Commission launched a new and more detailed CMU Action Plan (EU Commission, 2020). “Let’s finally complete the Capital Markets Union”, stated its new president, Ursula von der Leyen, in her opening address to the European Parliament.

Again, financial reform was intended to support an investment program, much bigger this time (750 bn euros), the Next Generation EU (NGEU). Hopes ran high. Quoting from the 2020 CMU Action plan launching document: “The CMU can speed up the EU’s recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. It can also provide the funding needed to deliver on the European Green Deal, make Europe fit for the digital age, and address its social challenges”. The Plan’s 16 lines of actions included actions and legislation on new market infrastructures, simplification of procedures, financial education, public disclosure, investor protection, insolvency procedures, harmonized supervision, and more. Only tax harmonization – the thorniest issue of all European agendas – was not part of that list.

The 2020 Plan was not more fortunate than its predecessor. In the end, Covid was overcome, the economy recovered and NGEU was put in motion – not without problems, but broadly on track. By contrast, CMU remained at the starting blocks. A survey by AFME, the association of European financial market participants, reports disappointment on almost all count (ESG finance being exception). The report concludes: “Unfortunately, when we take a longer view and consider the medium-term trends, it is clear that the EU has not made significant progress at improving its capital markets depth, particularly in terms of global competitiveness” (AFME, 2023).

Political obstacles have been mounting further lately. A last-ditch attempt by Germany and France to rally consensus behind CMU at the last EU Summit before the 2024 European elections was flatly rejected by a majority of EU member countries, especially small and medium sized ones (Financial Times, 2024).

As mentioned already, the CMU Plan combines two goals: strengthening market-based finance and integrating finance across national borders. The two goals are different and not necessarily of equal importance. Recent research actually tends to see the two types of financial structures not as alternative, as in earlier analyses, but as complements, each with merits and drawbacks relevant in different situations. This literature finds that optimal financial structures embody the best combination of the two elements. Let’s briefly look at the main suggestions coming from this very large body of research.

A long-standing broad conclusion from finance and growth literature – good surveys abound; see for example Levine (2003) – is that financial development benefits economic growth. King and Levine (1993) and Rajan and Zingales (1998), building on ideas by Schumpeter and Goldsmith, document a robust association between financial development and economic performance using international data. A causal association between the two was repeatedly confirmed in different institutional contexts and at different levels of economic developments. Importantly, however, this relationship ceases to hold in extreme circumstances, for example when financial ‘development’ becomes excessive and gives rise to excessively complex and opaque financial structures (Rajan, 2005; Zingales, 2015).

These conclusions refer to financial development in general. The evidence is much more ambiguous when one distinguishes between different financial structures. Levine (2002) uses data from 48 countries in the 1980-1995 period to compare two models of finance, the “bank-based view” and the “market-based view”. The “bank-based view” emphasizes the efficiency of banks in channeling saving to investment using information on borrowers’ characteristics obtained through long-standing client relations. By contrast, the “market view” emphasizes the beneficial role of competitive markets in extracting information, conveying it to investors and disciplining managerial behavior. According to this view, banks may hamper growth because they tend to use size and market power to extract rents from their borrowers. Levine (2002) finds no confirmation for either of these views. Quoting from his conclusion: “The results are overwhelming. There is no cross-country empirical support for either the market-based or bank-based views. Neither bank-based nor market-based financial systems are particularly effective at promoting growth. The results are robust to an extensive array of sensitivity analyses that employ different measures of financial structure, alternative statistical procedures, and different datasets.”

Levine (2002) advocates a “financial services view”, in which financial arrangements (contracts, markets, intermediaries) combine different saving-investment channels to resolve the informational imperfections inherent in credit markets. The best mix at any point in time depends on preferences, technology, habits and historical traditions. This approach logically connects with the “law and finance view”, popularized (Laporta et al., 2000, among others), who see the financial sector as a set of contracts and enforcement processes. The crucial point is how to make those contracts and enforcement processes effective with the best combination of customer relations and arms-length finance.

Using a more recent and extensive multi-country data sample, Demirgüç-Kunt et al (2012) find that as economic development advances and financial structures become increasingly sophisticated, economic growth tends to be associated more with financial markets than with bank intermediation. However, these authors are careful not to stress causal links between these phenomena. Their evidence is consistent with the idea that at any point in time, a combination of both arrangements can be optimal. Other factors may also be at play. As economic development progresses, institutions progress as well: judicial systems improve, transparency, accountability and reputational mechanisms strengthen, etc. This helps improve the functioning of financial markets, along the lines suggested by the “law and finance view”.

In interpreting this complex set of relations, one may look at the US financial system, a prominent example of a well-developed market-based finance. Looking at US financial developments over more than a century, Philippon (2008) concludes that the large fluctuations of the US financial structure were driven by the needs of the corporate sector. Young and innovative firms, rich of investment plans but short of internal cash and in need of external finance, make the financial sector expand. Concentrating on the post-WWII period, Greenwood and Scharfstein (2013) find that the great expansion of finance especially in the 1980s-1990s was driven by two sectors: asset management and household mortgages. In that period, the share of non-bank finance grew relative to total because these two activities grew largely outside the banking sector. This doesn’t need be the case always and everywhere, however. In Europe, for example, the asset management industry is to a large extent conducted directly by banks or controlled by them. Household mortgages are still originated and largely held on bank balance sheets.

An interesting interpretation comes from recent work by Acharya et al (2024, henceforth ACT). They first document the shift in weight since the 1980s within the US financial sector from banks to “shadow banks” (Non Bank Financial Intermediaries, or NBFI). Since NBFIs tend to focus their activity more on capital markets, this shift translates also in a growing importance of capital markets. Part of this movement is induced by prudential regulation, which imposes more stringent requirements on banks on the (dubious) assumption that systemic risk stems from them and not from NBFIs. However, banks and NBFIs are not substitutes of one another, in the sense of conducting different activities in parallel. They are rather complements, performing most financial functions jointly and depending increasingly on each other’s support.

Using new flow-of-funds data collected by the Federal Reserve, ACT show that the two sectors are closely interwoven and connected by a web of bilateral ties. For example, banks have shifted loan and mortgage business exposures out of their balance sheet, but retain part of the risk through lines of credit toward NBFIs and retaining senior tranches of structured products. As a result, bank risk does not disappear but takes on a different form. Most activities conducted by NBFIs, for example financing leveraged acquisitions, continue to depend on bank financing, on a regular basis and in the form of contingent funding NBFIs rely on under stress. As a result, activities of the two sectors cannot easily be disentangled. Systemic risk depends on NBFIs as much as it depends on banks: the latter run into trouble when the former do. This was clearly demonstrated during the 2008-2009 financial crisis, when risks originated outside the banking sector were quickly transmitted to banks (Volcker, 2009).

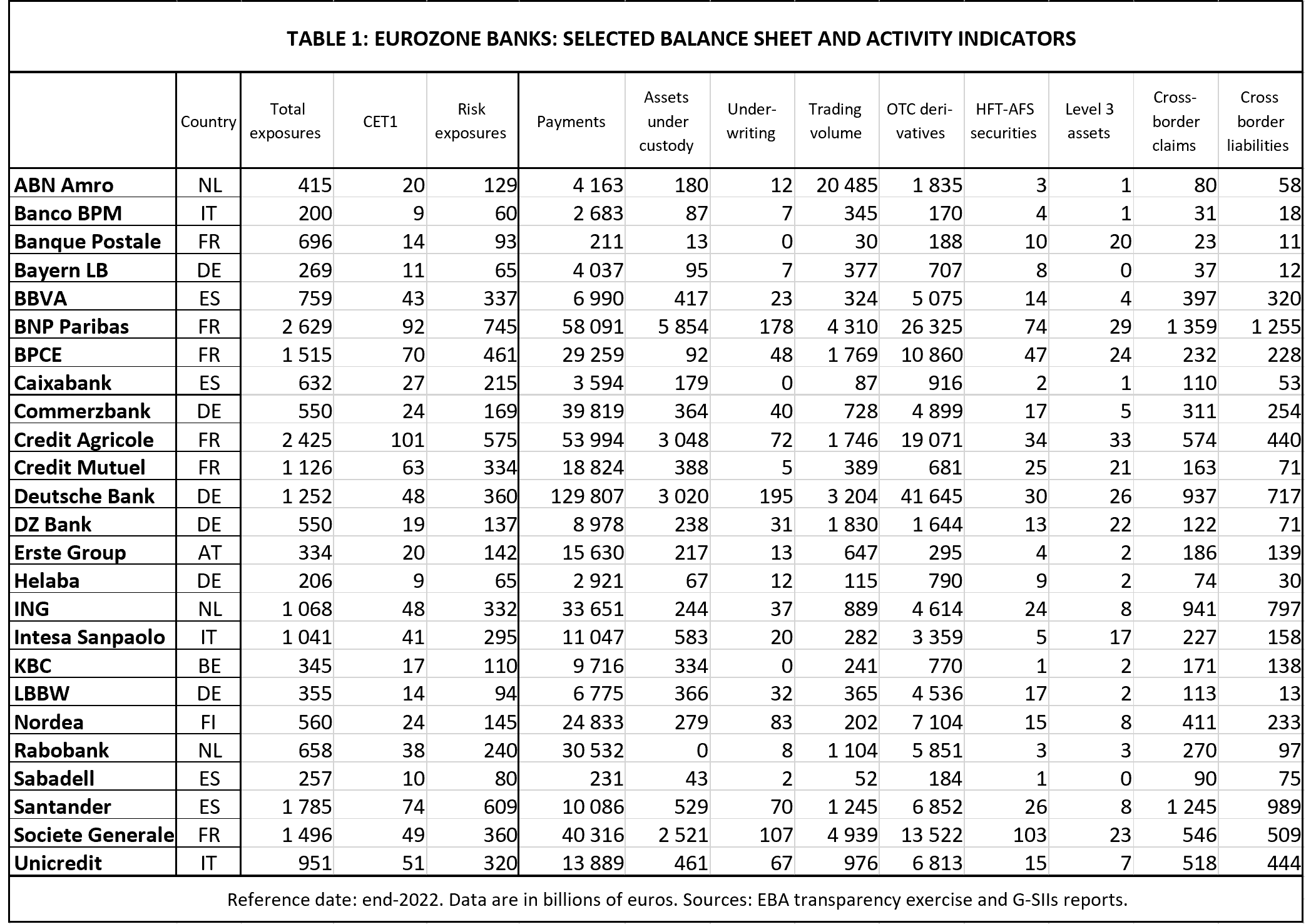

To assess where we stand, in this section we look at the data regarding capital market and wholesale activities of eurozone banks. Data on individual banks are rather scarce. We use information from two sources: EBA (2024a) and EBA (2024b). Table 1 contains balance sheet and activity indicators, dated end-2022, for 25 banking groups on which EBA conducts the Global Systemically Important Institutions (G-SIIs) exercise. The group includes all major banks so as to cover most capital market activities conducted by the eurozone banking sector as a whole.

Balance sheet indicators include total and risk-weighted exposures and CET1. Activity indicators available from the EBA G-SII exercise include payments (largely, wholesale international payments), assets under custody, trading and underwriting, OTC derivatives, securities held for trading or available for sale, level 3 assets (assets priced by means of models, hence deemed more risky), as well as cross-border assets and liabilities. Not all these indicators are related to capital markets; for example, payments may be linked to a variety of client-related services. Cross-border exposures (not only within the eurozone) express the extent to which the bank operates in more than one country. Unfortunately, important information is missing here; for example, securitization, stock market activities, fixed income and other exposures, money markets, primary dealership, etc.

With these caveats in mind, the following tentative messages emerge. First, wholesale and capital market activities by eurozone banks are extensive but spotty. In some banks, activities are skewed towards certain compartments: for example, Deutsche Bank reports an exceedingly high payments activity. In general, banks offer a diversified menu of services, including asset management, trading, OTC derivatives and payments. Moreover, there is a sharp distinction between few very large players and others. A small ‘élite’ of maxi-lenders offer all main services. Interestingly, those banks are also the ones that tend to have a comparatively large cross-border presence, in terms of both assets and liabilities. There is a relation between the propensity to engage in cross-border business and to offer wholesale and capital market services.

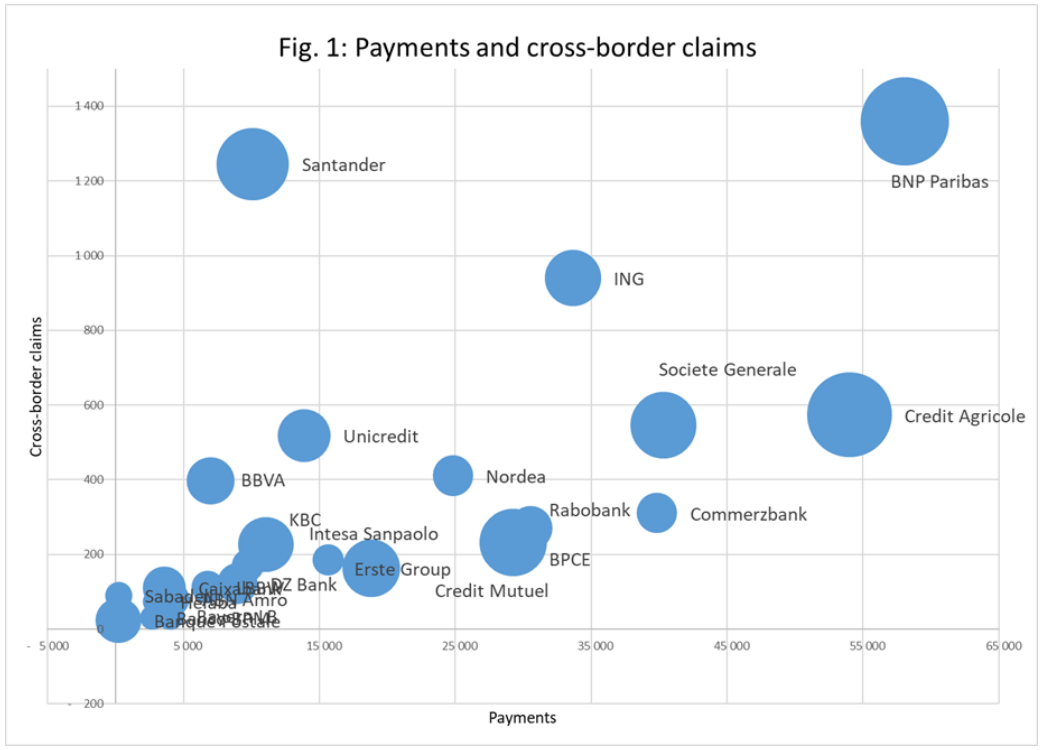

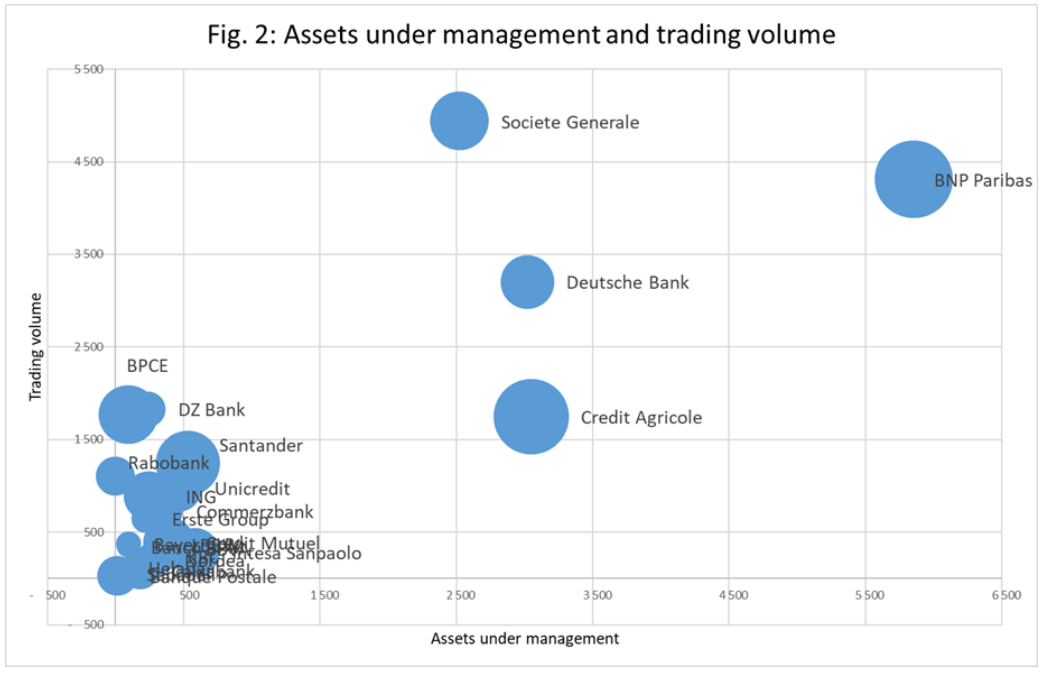

To show this idea visually, Fig 1 and 2 display scatter plots of pairwise activity measures. The size of the bubbles is commensurate to the size of the respective balance sheets. The two figures show the following pairs: Payments activity and Cross-border claims in Fig 1, and Assets under management and Trading volumes, in Fig. 2. Please note that Deutsche Bank in Fig. 1 and Abn Amro in Fig. 2 are out of scale. The choice of pairs is not intended to imply a causality relation. The charts suggest a positive relation between the aforementioned measures; a small group of banks “stand out” in terms of most key parameters: size, cross-border openness and capital market activity.

Though these data should not be over-interpreted, the fact that a small number of large players display large values of all indicators in question suggests there is a complementarity between size, the propensity to operate across-borders and that of engaging in capital markets. Policy efforts aiming at enhancing both cross-border integration and capital markets can complement each others, and should be tailored to the specific characteristics of those banks. Other small and medium-sized eurozone lenders that tend to offer traditional banking services within national boundaries are likely to play a less important role from the viewpoint of fostering integration.

Failure by the Commission to jump-start CMU in recent years may have depended on the overambition of building an integrated capital market from a greenfield in a situation where not only banks dominate the financial sector, but eurozone banking itself is not integrated.

Recent research is de-emphasizing the distinction between bank-based and market-based financial structures. The two forms are complementary, not alternative; neither of the two is superior regardless of specific conditions and the starting point. Certain functions are better performed by banks, others by non-bank intermediaries or unintermediated arrangements. The financial needs of corporates and households are better served by combinations of these elements.

Given the eurozone’s starting situation, in which banks dominate and some of them (very large within the continent, but not sufficiently large globally) conduct significant but sporadic capital market activities, one may consider spearheading banking integration first. This requires focusing on the needs of large players by removing regulatory obstacles that constrain them largely within national borders. While banking integration proceeds, capital market will have a better chance to develop. Segments especially promising because of their complementary with established eurozone banking include securitization arrangements and equity-based financing platforms for innovative start-ups.

In a recent paper submitted to the European Parliament (Angeloni, 2024) the suggestion was made of removing the regulatory obstacles in EU law which prevent or discourage the cross-border presence of large banking groups. If this is done, their internal cohesion needs strengthening, especially under stress, to avoid that entities in distress may be “renationalized” and wound down using national taxpayer resources. More instruments and powers need to be granted to the European resolution authority so that it can take exclusive responsibility for crisis management of large eurozone cross-border groups.

The strategy could be summarized as follows (see the aforementioned paper for details):

These proposals are complex, affecting multiple parts of today’s EU banking law, but can all be implemented by normal legislation. By attacking head-on the obstacles that prevent a genuine banking union, they can also help starting the capital markets union that has so far been elusive.

Acharya, Viral V., Cetorelli, N. and B. Tuckman (2024). “Where Do Banks End and NBFIs Begin?” NBER Working Paper #32316.

AFME (2020). “Capital Markets Union; Key Performance Indicators”; October, see here.

AFME (2023). “Capital Markets Union; Key Performance Indicators”; November, see here.

Angeloni, Ignazio (2024). “The Next Goal: euro area banking integration. A single jurisdiction for cross-border banks,” February, Report submitted to the European Parliament.

Demirgüç-Kunt, Asli, Erik Feyen, and Ross Levine (2012). “The Evolving Importance of Banks and Securities Markets”, The World Bank Economic Review 27(3) 476–490.

EBA (2024a). EU-Wide Transparency Exercise; see here.

EBA (2024b). Global Systemically Important Institutions (G-SIIs); see here.

EU Commission. (2015). “Action plan on building a capital markets union“; see here.

EU Commission. (2020). “Action plan on building a capital markets union“, see here.

EUROFI (2024). “Update on the progress made on CMU”, in Eurofi Regulatory Update, February; see here.

Financial Times (2024). “Majority of EU states object to capital markets reform push”, 29 April.

Greenwood, Robin and David Scharfstein. (2013). “The Growth of Finance”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 27(2): 3–28.

King, Robert G., and Ross Levine. (1993). “Finance and Growth: Schumpeter Might Be Right.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 108(3): 681–737.

Laporta, Rafael; Lopez de-Silanes, Florencio; Schleifer, Andrei; and Vishny, Robert W. (2000). “Investor protection and corporate governance”, Journal of Financial Economics 58, 3-27.

Levine, Ross. (2002). “Bank-Based or Market-Based Financial Systems: Which Is Better?” Journal of Financial Intermediation 11(4): 398-428.

Levine, Ross. (2003). “More on Finance and Growth: More Finance, More Growth?” Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis Review 85(4), 31-52.

Rajan, Raghuram. (2005). “Has Financial Development Made the World Riskier?” NBER Working Paper 11728.

Rajan, Raghuram G., and Luigi Zingales. (1998). “Financial Dependence and Growth.” American Economic Review 88(3): 559 – 86.

Volcker, Paul (2009). “Think more boldly”; interview with the Wall Street Journal, 14 December.

Zingales, Luigi. (2015). “Presidential Address: Does Finance Benefit Society?” The Journal of Finance 70(4): 1327-1363.