The analysis in this blog draws on the recently published Finance in Africa report of the EIB.

Abstract

The private sector in Africa is facing constraints on both domestic and overseas sources of finance, undermining the critical investments needed to drive development. The IMF (2023) highlight that this problem intensified following the shocks caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Covid-19 pandemic, as global financial markets tightened. A lack of access to finance has been one factor holding back more rapid development on the continent over the last twenty years.

Understanding the role of the domestic financial sector in promoting intermediation is critical in terms of supporting development. The European Investment Bank (EIB) has completed its annual survey of banks in Africa in 2024, supported by Making Finance Work for Africa. We surveyed 51 banks in sub-Saharan Africa to understand how banks are coping with the challenging financial environment. In this article/paper, we share some key insights from the report, particularly in relation to the financing of the economy.

Economic progress indicators, like income per head or Africa’s share in global GDP, have improved at an unsatisfactory pace over the last twenty years, despite strong economic growth during much of this period. A factor frequently cited as restricting development in Africa is the relatively low level of industrialisation on the continent. The share of industry in GDP has not grown over the last twenty years and agriculture plays an outsized role in the economy compared to other regions. Africa also has relatively low participation in global value chains. A large share of trade for African countries is with more developed partners and Africa often plays the role of commodity exporter. The African Union Commission/OECD (2022) Africa’s Development Dynamics report shows that processed and semi-processed goods account for 79% of intra-African exports, compared with just 41% of exports to other destinations. This means that the industrial content in intra-African exports is much higher than that of exports leaving the continent.

Boosting industrialisation in Africa by mimicking the approach of other countries (such as those in Asia) and attracting manufacturing production via cheap labour may not be successful. Ignatenko et al. (2019) report that participation in global value chains is linked to various factors, including proximity, common language, currency volatility, rule of law, infrastructure, trade barriers and labour costs. Even with cheap labour in Africa, many of these factors represent a structural barrier to greater global value chain participation. Second, the literature points to increased sophistication in global value chains, making them less labour intensive. For example, Sen (2019) shows that countries with higher trade integration require fewer workers per unit of manufacturing production, and Pahl and Timmer (2019) provide long-running evidence on the declining employment content of exports. These trends could accelerate if recent developments in artificial intelligence are incorporated into manufacturing processes. A problem for Africa has been meeting the strict product standards required for exporting to advanced economies, and this requirement could become more onerous for certain product categories.

Nonetheless, developing regional value chains could accelerate industrialisation on the continent and the agriculture sector offers a major opportunity. There are 26 countries in sub-Saharan Africa where more than 40% of the population work in agriculture. In addition, Christiaensen (2020) reports that three-quarters of African adults classed as poor work in agriculture – too many for the economy to absorb if these workers were to be redeployed in other sectors. Instead, increased productivity and greater industrialisation are required in the sector. African agricultural imports and exports have been growing over the past decade but import values have grown more rapidly than export values, highlighting opportunities for increased regional processing and distribution of agricultural products, helping to meet this growing agricultural import demand. As African countries become wealthier, the demand for agricultural products will grow further.

Driving industrialisation and private sector development means overcoming key structural constraints in the economy, particularly inadequate levels of infrastructure, low skills attainment and a lack of finance. On the financing side, many external sources of finance for Africa, such as overseas development assistance, foreign direct investment and portfolio flows have all declined in the last decade. Additionally, the government sector, which is a major driver of investment, also faces financing problems. Public debt levels and debt servicing have increased further following the pandemic and government revenue is equal to 18% of GDP, lower than in other developing regions.

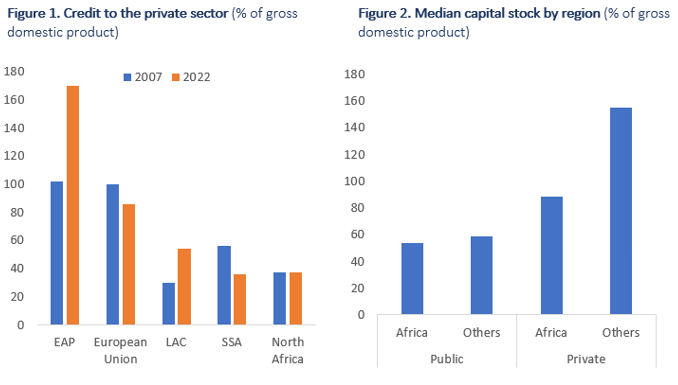

Against this background, the finance provided by banks is critical. However, Sub-Saharan Africa has seen credit as a share of GDP decline over the last 15 years. Private sector credit in 2022 was 36% of GDP, a decline from 56% of GDP in 2007 (Figure 1), highlighting that credit provision to the private sector has failed to keep pace with economic growth. In North Africa, credit as a share of GDP between 2007 and 2022 was unchanged at 37%, as credit expansion in countries like Morocco and Tunisia was offset by a sharp drop in credit as a share of GDP in Egypt.

The relatively low level of private sector credit may be limiting the rate of private investment, partly through degradation of the private capital stock. According to International Monetary Fund data,#f1 the median private capital stock was equal to 88% of GDP across 48 African countries in 2019, which is the latest year for which data are available. For the other 113 countries across the globe in the sample, the median was 155% of GDP (Figure 2). This means that African countries have a lower private capital productive base relative to other regions. In contrast, public capital stock ratios across the two groups of countries are broadly similar, at 54% of GDP in Africa and 59% in other countries, meaning the biggest difference between the two sets of countries is in their private productive capacity. Lack of finance may be hindering this private productive capacity, as in many advanced and developed countries, there is an empirical link between bank credit and firm investment.

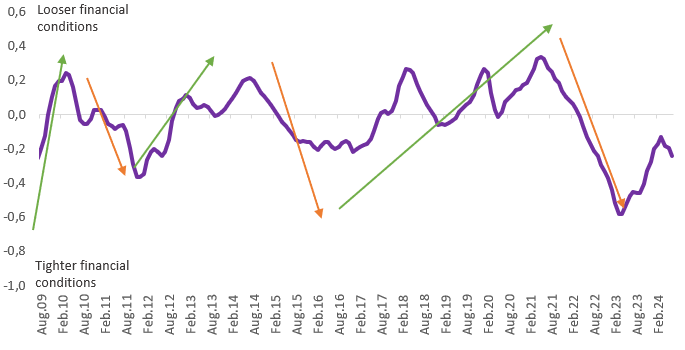

Encouragingly, financing conditions are showing signs of easing, based on the EIB Financial Conditions Index (FCI) for Africa based individual indices for ten countries, representing about 60% of Africa GDP. Seven variables are included: credit growth (private and public sectors), the corporate lending spread,#f2 the 12-month change in the nominal exchange rate change vs. the US dollar, the 12-month policy rate change, the 12-month change in the stock market, and inflation. The index aims to capture the difficulties facing the private sector, particularly when it comes to financing. The period after war in Ukraine represented the most severe peak-to-trough tightening of financial conditions in the last fifteen years (Figure 3). The tightening appeared to be more severe for countries with weaker sovereign creditworthiness. For example, Kenya, Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa have all experienced some form of macroeconomic difficulties during the period, which was reflected by tighter financial conditions. The tightening of the index started to wane around mid-2023, particularly for the smaller countries with fewer macroeconomic imbalances, reversing approximately 40% of the peak-to-trough tightening.

Figure 3. Financial conditions index for Africa

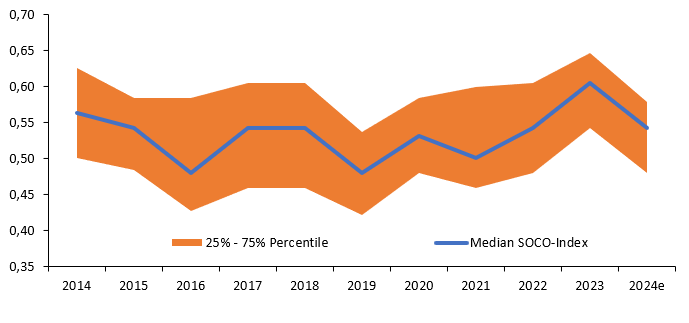

Our Severity of Crowding Out (SOCO) index also supports the view that while access to finance remains a key structural constraint, the cycling deterioration in financing condition following the pandemic and war is at last beginning to abate. The SOCO index aims to capture the degree to which lending to the public sector is restricting lending to the private sector. African banks have increased their exposure to sovereign debt in recent years, which amounted to 17.5% of assets in 2023 from 10.3% in 2010, raising the potential for bank losses in the event of a debt default or restructuring. At the same time, there is a decreasing trend in banks’ private sector lending to 38% of assets in 2023 from 42% in 2010, posing concerns about the severity of crowding out. While the SOCO Index pointed to severe crowding out pressures in 2023 due to high public debt issuance combined with a resurgence in demand for private credit, these pressures eased somewhat in 2024, helped by loosening financial conditions, leading to better funding conditions for banks, including increased access to international markets (Figure 4).

Figure 4. EIB Severity of Crowding Out (SOCO) Index

African Union Commission/OECD (2022). “Africa’s Development Dynamics 2022: Regional Value Chains for a Sustainable Recovery.” OECD Publishing, Paris.

Christiaensen, L. (2020). “Agriculture, Jobs, and Value Chains in Africa.” Jobs Notes No. 9. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Ignatenko, A., Raei, F. and Mircheva, B. (2019). “Global Value Chains: What are the Benefits and Why do Countries Participate?” IMF Working Paper.

International Monetary Fund (2023). “The Long Squeeze: Funding Development in the Age of Austerity.” Regional Economic Outlook Analytical Note, sub-Saharan Africa, October.

Pahl, S. and Timmer, M. P. (2019). “Do Global Value Chains Enhance Economic Upgrading? A Long View.” The Journal of Development Studies, 56(9), 1683–1705.

Sen, K. (2019). “What explains the job creating potential of industrialisation in the developing world?’’ The Journal of Development Studies, 55(7), 1565-83.

This is the difference between corporate interest rates and the policy rate.