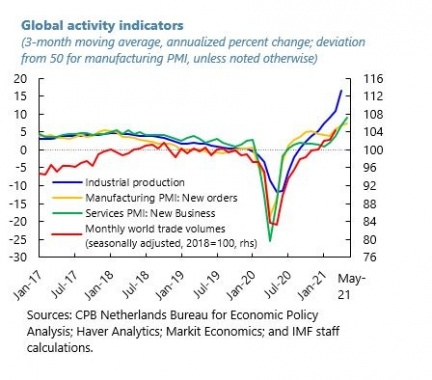

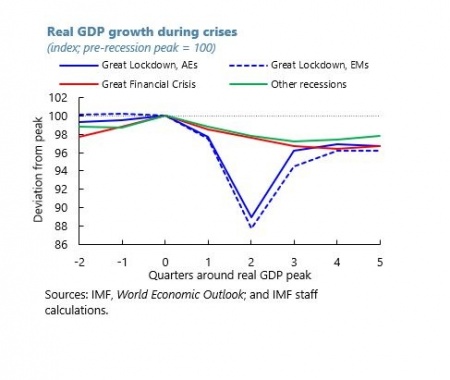

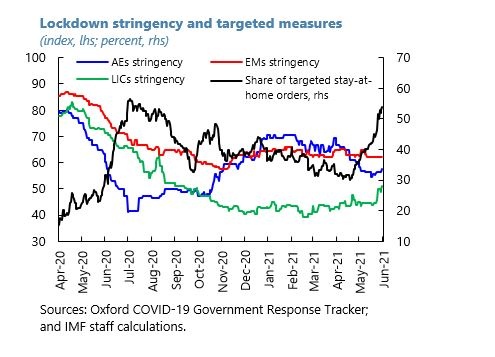

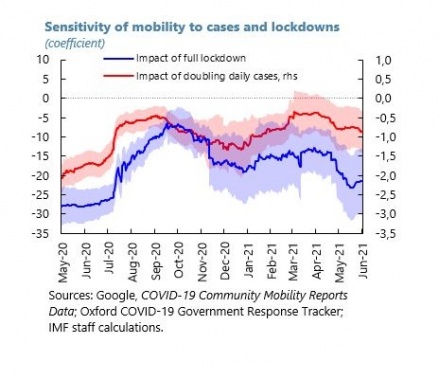

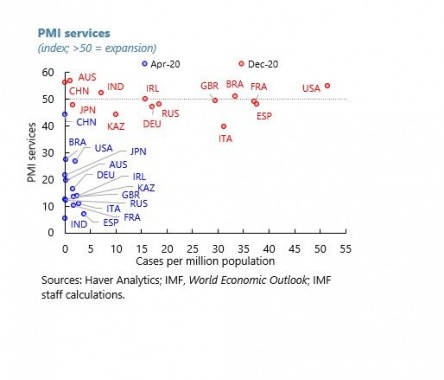

Which factors made it a “V-shaped” recession for countries where vaccination is more advanced? There are, at least, four concurring reasons: 1) strong policy response; 2) no financial crisis after the initial drop of the markets in March; 3) scientific breakthrough and development of the vaccine happened much faster than anticipated; 4) adaptation and learning. The last factor was particularly interesting. Agents (households, governments, and firms) learned to live with the pandemic and recurrent lockdowns. This learning is illustrated in Figure 2. The left panel shows that stringency measures declined over time. The middle panel shows that the sensitivity of mobility to lockdowns and increases in COVID-19 cases declined over time. Also, the contraction in the service sector that was so prominent in April 2020 was generally irrelevant in December (right panel).

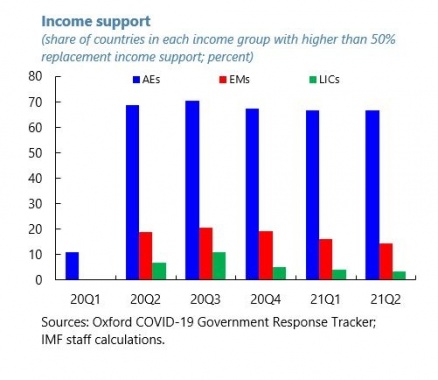

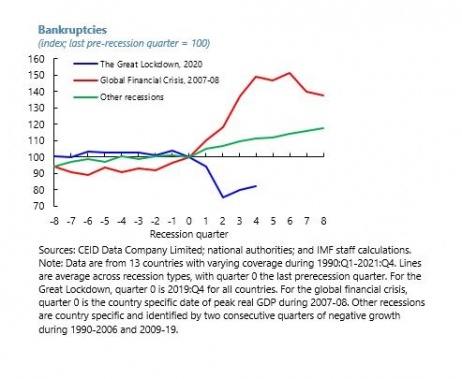

One key factor contributing to the V-shaped recession is the exceptional policy support. This took the form of direct household support (also in emerging economies) and of forbearance. The chart below illustrates both facts. In sharp contrast with what happened in previous recessions, bankruptcies went down in advanced economies. This was certainly important to avoid the deepening of the crisis but creates a challenge for the future as regulatory forbearance may have hidden ‘zombie firms.’

Figure 3: Exceptional support (the snow blanket effect)

Fact IV: Unusual saving behavior

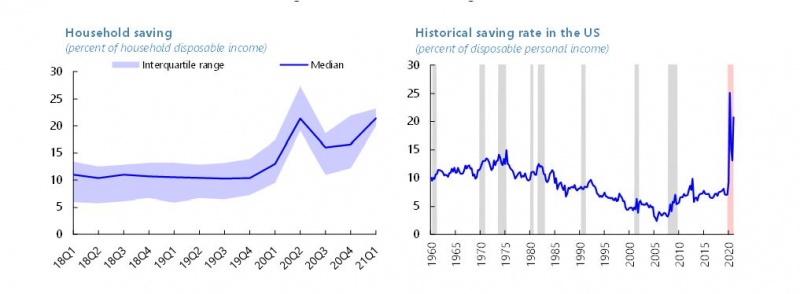

If support to companies may have created zombie firms, support to households has had clear effects on household saving, which boomed in all advanced economies (left chart). This is in contrast with previous recessions in the US (right chart). The unusual behavior of the household saving rate is because households had few opportunities to spend the direct fiscal support and will help the incipient recovery once mobility restrictions ease. The US saving rate spikes also reflected the especially large and broadly targeted government transfers.

Figure 4: Record saving rate

Sources: Haver Analytics; US Bureau of Economic Analysis; IMF staff calculations.

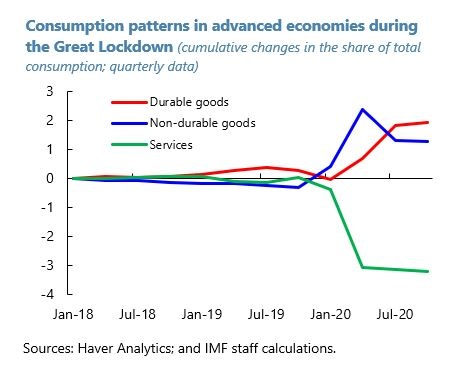

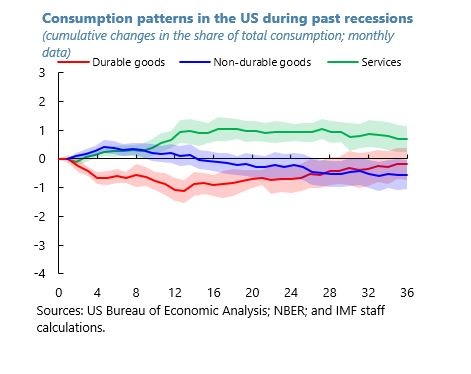

Fact V: Unusual consumption patterns

If the saving rate was abnormal, how do consumption patterns look like? They were also very different during the Great Lockdown compared to other recessions. Consumption of durable goods boomed while the consumption of services collapsed, consistent with the evidence showing that the pandemic hit contact-intensive sectors harder, and, with people spending more time at home, increased demand for electronics, furniture, and other consumer goods.

Figure 5: Unique consumption patterns