On 13 April, US Treasury Secretary Yellen gave a speech to The Atlantic Council in which she stressed:

“Going forward, it will be increasingly difficult to separate economic issues from broader considerations of national interest, including national security…

On some issues, like trade and competitiveness, this will involve bringing together partners that are committed to a set of core values and principles…

Favouring the friend-shoring of supply chains to a large number of trusted countries, so we can continue to securely extend market access, will lower the risks to our economy as well as to our trusted trade partners.”

UK Foreign Secretary Truss then proposed a ‘Network of Liberty’, adding “For too long many have been naïve about the geopolitical power of economics,” China’s rise “isn’t inevitable… We represent half of the global economy. And we have choices,” and the West should use the G7 as an “economic NATO” and commit to “collective economic defence… all for one and one for all.”

Japan has long advocated onshoring some production and is openly subsidising firms that want to bring supply chains home.

Even the EU is getting cold feet about China’s backing for Russia’s position on Ukraine and its economic coercion of Lithuania, and is talking of both diversification and supply chain resilience.

However, talk, like Chinese imports, is cheap. Many in markets remain rightly sceptical whether firms or consumers will really be willing to pay the higher structural cost of production outside China, or the frictional cost of moving supply chains away from it. Yet the tide does seem to be turning. Even free trade advocates The Economist note that ‘The structure of the world’s supply chains is changing’. The Financial Times, equally opposed to the idea of geopolitical trade blocs and friend-shoring, warns that despite their hopes for the opposite, “It is possible –perhaps even probable– that the world system will shatter.”

The US recently launched a new Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), which, while only a place-holder, could be fleshed out into a trade bloc that does not lower tariffs between members but raises them against China.

The US has also signed a ‘21st century deal’ with New Zealand including greater defence co-operation; passed the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act to block imports from Xinjiang; agreed the ‘Blue Pacific’ partnership for Pacific Island nations to push-back against China; and the G7 has announced a $600bn infrastructure fund to rival China’s Belt and Road. The US CHIPS act to boost domestic semiconductor production also looks close to the finish line, alongside a slew of investment.

On the other hand, US President Biden has suggested removing some tariffs on China – though his Trade Representative wants to keep “strategic” ones as “leverage” for negotiations, and major changes are unlikely to occur.

In short, the direction of trade travel is clear, but perhaps not the speed, nor the final destination. Yet two steps forward, one step back is still one step at a time out of China and towards other markets.

Firms also appear keen to move supply chains to reduce rising logistical and geopolitical risks of different forms.

FDI data shows China’s share of total new inward investment has dropped from around 14% to just 5%, while US imports from Vietnam and India are rising compared to those from China.

In some cases a production shift is slowed by related industries also needing to. Anecdotally, Indian textile firms are seeing inquiries about taking production from China, yet they are turning it down due to a lack of looms… which China produces and will not sell to them. Once new loom supply chains are also set up, a much larger shift in overall production from China to India may be seen.

This points to a so-called “J” curve, or “ketchup effect”.

In short, the argument that friend-shoring will not happen does not reflect what the leading trend of data already suggests: and that was pre-Ukraine, China lockdowns, and geopolitical tensions raised by NATO’s latest Strategy Concept declaring that China’s “stated ambitions and coercive policies challenge our interests, security, and values,” which hardly argues for more trade and investment.

Indeed, if we do see a friend-shoring trend ahead, it is likely to be rapidly non-linear. Things would undoubtedly accelerate were Western governments to offer financial incentives to do relocate, as in Japan or with US semiconductors; or even to give clearer guidance on the emerging geopolitical architecture, rather than forcing each firm to read those strategic tea leaves for themselves.

This report will attempt to ‘front-run’ such potential geoeconomic shifts to estimate the potential for friend-shoring globally.

We need to have a clear picture of i) where China is producing export goods; ii) the total value added associated with those goods; iii) how many people are working on those goods; and iv) to what extent these exporting industries depend on Western demand.

China produces the goods it exports in mainly six key provinces: Fujian, Guangdong, Jiangsu Shandong, Shanghai, Zhejiang, and, to a much lesser degree, Xinjiang. The export intensity is remarkable, reaching over 80%. Taken together, these seven locations are responsible for 80% of China’s total exports and account for 469m people, a little over a third of China’s official population.

GDP per capita varies sharply between those provinces, but may surprise those who still associate China with low-cost production. While Xinjiang’s GDP per capita is around $10,000, Shanghai’s is over $27,000, and Guangdong in the industrial heartland of the Pearl River Delta is around $15,500.

Of course, labour does not capture 100% of GDP, and China’s labour share is far lower than in most other markets. We include that lower adjusted figure in our computations.

So, we know where China produces exports; that OECD data show 52% of imported trade value-added (TVA) in the West originates in China; how many people live in China’s exporting provinces; the relative numbers employed in export-related industry there; and how much they ‘cost’ on average in dollar terms.

Putting these figures together we estimate that 28m Chinese jobs directly rely on exports to the West.

We can now look at where this pool of friend-shoring supply might be demanded, were this trend to emerge.

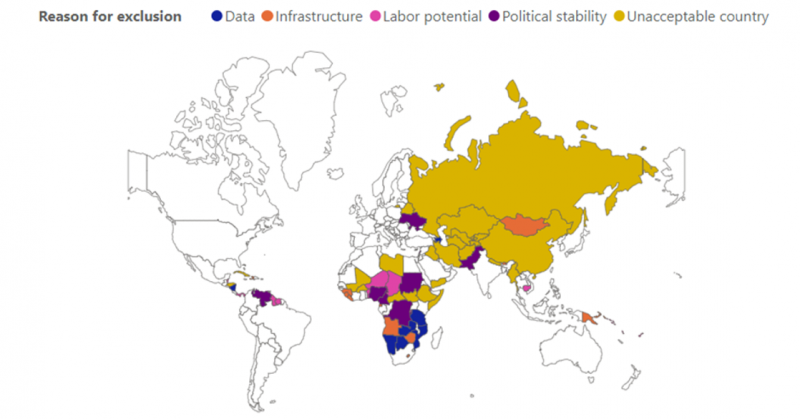

Figure 1: My mum said I can’t be friends with you

Source: RaboResearch

Naturally, not every country is able to take on some of China’s industrial production. We filter all global countries on a variety of factors:

We dismiss countries above/below key thresholds in these regards, which immediately removes a swathe of potential friend-shoring locations across Africa and central Asia, with a few in Southeast Asia and Latin America also excluded.

We then score all remaining countries based on:

We fully recognise that in the ‘geopolitical’ world driving friend-shoring, China will not be pleased with countries ‘stealing’ its manufacturing jobs. Consequently, we account for potential Chinese repercussions. We assume that in the worst case scenario, China halts trade with specific countries.

That implies that countries are only willing to take ‘Chinese’ jobs and export more to the West if the added value of the jobs they receive is larger than their current net TVA from trade with China.

This approach doesn’t factor in any reliance on Chinese key technology, or any risks of non-trade retaliation. However, it should be a fairly reliable indicator for the ‘trade trade-off’ that countries must make.

Additionally, even though China is more than capable of coercing smaller countries individually, it might choose not to do so when it has to fight a number of smaller countries simultaneously.

However, we have yet to divide up the 28m ‘Chinese’ jobs that are up for grabs between the actual contenders. As just noted, some countries will be reluctant to pursue Chinese manufacturing jobs in fear of repercussions. Others will only be able to handle a small jobs shift due to capacity constraints. Moreover, firms will not want to put all their eggs in one basket again so readily. In short, we will not see all China’s Western export-related move to just India or Vietnam, even if we will see new clustering effects.

The number of jobs we ‘allocate’ to friend-shoring per country depends on its attractiveness based on the factors that we mentioned earlier. We then divide the jobs between contenders by assuming the most attractive countries get the jobs first.

Each country then hits its near-term ‘absorption capacity’, which varies, but is based on the heuristic base of how quickly China managed to absorb Western jobs when they were shifted to it. (Which many economists said would not happen at the time!)

The ‘China jobs’ then continue to flow on to the second most attractive country, which has its absorption limit, then the third, with its, and so on. For a graphical metaphor, imagine pouring liquid from a large container into a variety of smaller containers that fill slowly, starring from the most attractive and working down the preference scale.

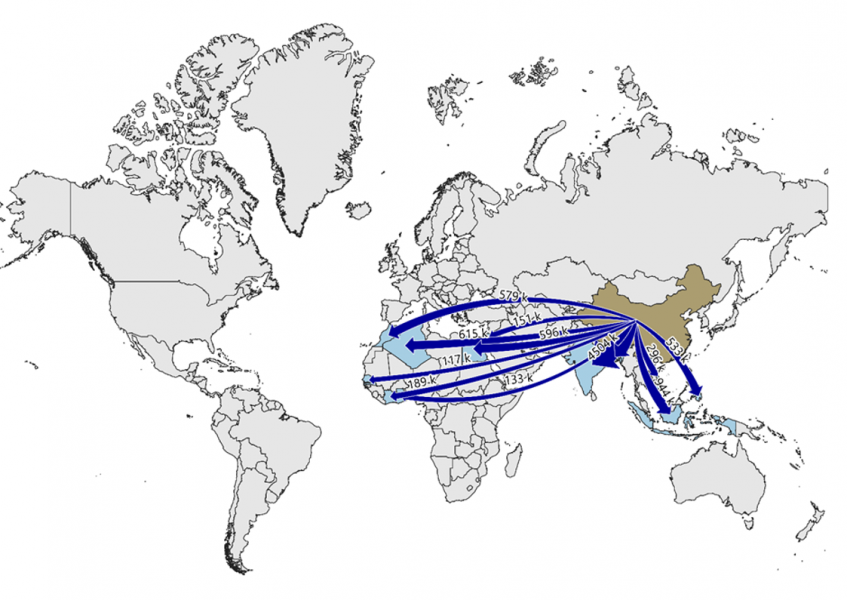

Low-tech manufacturing jobs

We expect that a fair share of the jobs at stake will go to India. Its vast potential labour force, low wages, rule of law, improving infrastructure, and geopolitical status within the Quad (despite a legacy friendship with Russia), all make it a very interesting prospect. Overall, it can take 4.5m jobs in these sectors from China.

For Bangladesh (1.2m jobs), Indonesia (0.9m), and some other countries in south-east Asia (Vietnam 0.3m, Philippines 0.5m), the situation is broadly comparable.

Counter-intuitively to some, several African countries are also attractive given their low wages. Senegal and Ghana, for example, but also Algeria, Morocco, and Egypt. However, the sheer population sizes of India and Bangladesh is likely to dominate the flow of low-tech manufacturing jobs.

Figure 2: Low-tech friend-shoring job flows from China

Source: RaboResearch

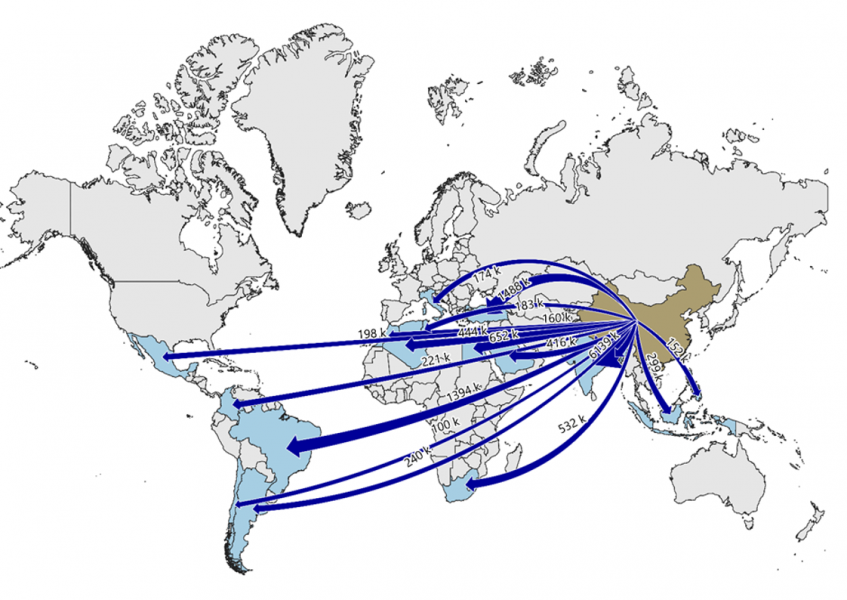

Medium-tech manufacturing jobs

India (6.1m jobs), Turkey (1.5m), and Brazil (1.4m) are the top contenders for medium-tech manufacturing jobs.

First, each of those countries still has considerable untapped manufacturing potential. Secondly, wage costs are relatively low, especially compared to Western standards.

African countries can also profit from an exodus of Chinese jobs. Egypt, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and South Africa all stand to benefit. Even though those countries do not head the ranking in terms of attractiveness (they have a relatively small medium-tech manufacturing sector, whilst their political systems are not always the most stable historically), there are plenty of jobs up for grabs – and there are only a limited number of countries that meet the criteria we have elaborated upon earlier.

Of course, Mexico also sees job gains, and so do Chile, Colombia, and Argentina. Even Italy enters this arena.

Figure 3: Medium-tech friend-shoring job flows from China

Source: RaboResearch

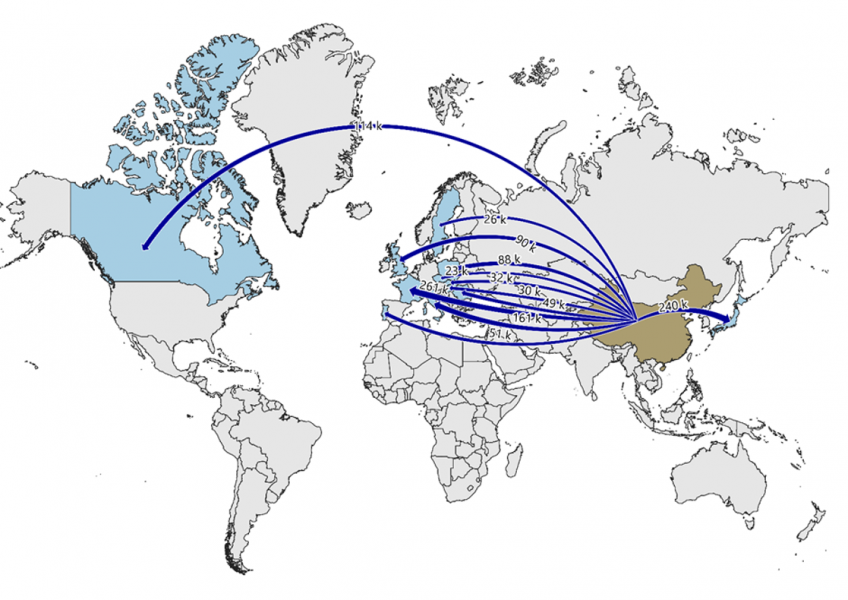

High-tech manufacturing jobs

In contrast to the projected distribution of friend-shoring of low- and medium-tech jobs, we expect high-income countries are relatively attractive for high-tech jobs.

This can be explained by the fact that labour costs play a smaller role in this sector, which is more capital intensive, and higher-income countries already have sizeable high-tech manufacturing sectors.

There are a couple of omissions from our projections, however. South-Korea has a very competitive high-tech sector, but also has an extremely positive trade balance with China, which might deter it from being too assertive. The same can be said for Malaysia. Singapore has an advanced manufacturing sector, but where the potential labour force is a limiting factor.

The US is also not on the list, but we believe in reality, and based on the survey evidence already shown, some US states such as Texas and Arizona will certainly benefit.

Figure 4: High-tech friend-shoring job flows from China

Source: RaboResearch

Nobody can say for sure if friend-shoring will happen or not. The world is changing very rapidly, and countries one would once assume were friends may not be so forever.

Moreover, with inflation rising, is a further increase in the cost of production really a good idea now? Many businesses will say no.

At the same time, China will almost certainly push back against friend-shoring. As Xi Jinping had already warned in January 2021, “We should increase the dependence of international supply chains on China and establish powerful retaliatory and menacing capabilities against foreign powers that would try to cut supplies.” How menacing will things get?

In short, this is not going to be a quick, easy, or painless exercise.

Nonetheless, the historical and fundamental analysis that had already led us to predict the “perhaps probable” shattering of “the world system” now being flagged by the Financial Times tells us that geopolitics will eventually trump neoliberal economics, making friend-shoring more likely to happen. Indeed, the above Chinese threat is more likely to accelerate than delay the process, after a lag.

True, the scale that we see potential friend-shoring happening on in this report may take years, geopolitics depending; and it may never occur completely as we project.

Indeed, for many Western firms the appeal of reshoring completely, rather than taking another risk on another emerging market, may appeal more – especially with government support. There are certainly areas of even G7 economies that have low enough regional GDP per capitas that they would welcome jobs close to the levels China could likely ‘offer’. Of course, that shift in final destination doesn’t matter much for China.

Overall, the survey evidence, the leading data, and the global backdrop all suggests that the rising risk is of at least a partial friend-shoring transition along the lines of what we describe: Some friends will be reunited. Others will be parted. And global trade flows, geoeconomic and geopolitical power, and financial markets will all move accordingly.