The views expressed in this column are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bank of Greece and the European Investment Bank.

Abstract

Utilizing a narrative database on structural reforms in 25 OECD countries from 1985 to 2020, we investigate the effects of labor and product market reforms on gross capital inflows. By applying the local projection method and addressing reform endogeneity with the Augmented Inverse Probability Weighted estimator, we find that structural reforms have a positive medium-term effect on both direct and portfolio investment. In particular, reforms boost investment, especially in environments of high-quality financial institutions and amid low public debt.

Capital inflows are vital for economic progress, as they stimulate growth by enabling investment in infrastructure, businesses, and financial products (Igan et al., 2020; End, 2024). These flows contribute to employment growth, boosts productivity, and enhance prosperity (Ostry et al., 2011; Blanchard et al., 2016). Inflows, such as FDI, also bring knowledge, technology, and managerial skills that improve domestic firms’ competitiveness and foster innovation (Ning and Wang, 2018; Ning et al., 2023). Additionally, they strengthen resilience to external shocks by facilitating global market access and infrastructure development, though regulatory control is needed to prevent risks like financial instability.

The recent Draghi Report (Draghi, 2024) indicates that the EU requires substantial additional amount of investment to meet its objectives; however, both private and public investment levels remain insufficient despite abundant private savings.

Structural reforms could serve as a crucial policy tool in this context, not only to drive growth and productivity but also to address financial frictions that can cause capital inflows to be misallocated to less productive firms, thereby hindering economic growth (Reis, 2013; Gopinath et al., 2017). By reshaping the economy and adjusting regulatory frameworks, structural reforms facilitate the reallocation of resources to more productive firms, act as a pull factor for sustainable investment, and mitigate risks of capital reversals and crises (López and Stracca, 2021).

The core findings of our study highlight the beneficial impact of product and labor market reforms on direct and portfolio investments. However, the benefits of reforms do not materialize in the short term but become evident in the medium-term. Additionally, product and labor market reforms affect positively capital inflows, particularly when implemented in environments characterized by a low government debt ratio and by more developed financial markets and institutions highlighting the importance of institutional quality (Masuch et al., 2018; Draghi, 2024).

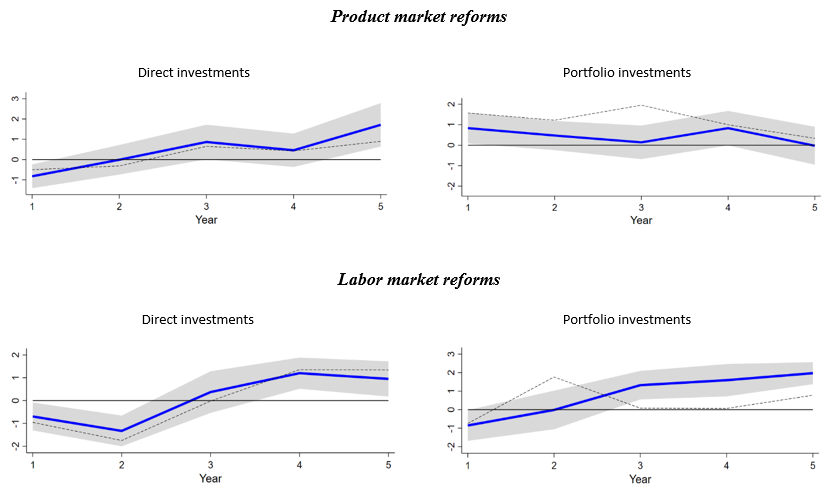

Overall, the results suggest that product and labor market reforms have a positive effect that needs time to be materialized. As shown in Figure 1, product and labor market reforms initially have a negative effect on direct investment, which turns positive after the third year. Over the five-year horizon, these reforms lead to a cumulative increase in direct investment of about 2% and 1% of GDP, respectively.

The response profile of direct investment suggests that the benefits of product market reforms do not materialize in the short term but become evident in the medium term. This lagged effect may be due to the time required for (a) firms to adapt to the new regulatory environment and (b) reforms to positively affect market perceptions, thereby boosting investor confidence and investment inflows (see, e.g., Alesina et al., 2005;). Additionally, potential investors may wait to see that the reforms are implemented consistently and are not reversed over time.

Figure 1. The average treatment effect (ATE) of product and labor market reforms on direct investment and portfolio investment using the AIPW method.

Notes: The solid blue line represents the (ATE- AIPW) impulse response of direct investment or portfolio investment following a product (upper panel) and labor market (lower panel) reform. The light grey shaded area indicates the 90% confidence interval using bootstrapped standard errors. The thin dashed black line is the cumulative impulse response from the simple unweighted LPs.

Structural reforms in the product and labor markets are pivotal for enhancing a country’s economic resilience and attractiveness to investors by fostering regulatory efficiency and market adaptability (see, e.g., Rodrik, 1996;). However, such reforms may influence capital inflows differently depending on various macroeconomic and institutional conditions. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for timely deregulation efforts and informed economic policy (see, e.g., Acemoglu and Robinson, 2012; Masuch et al., 2018;).

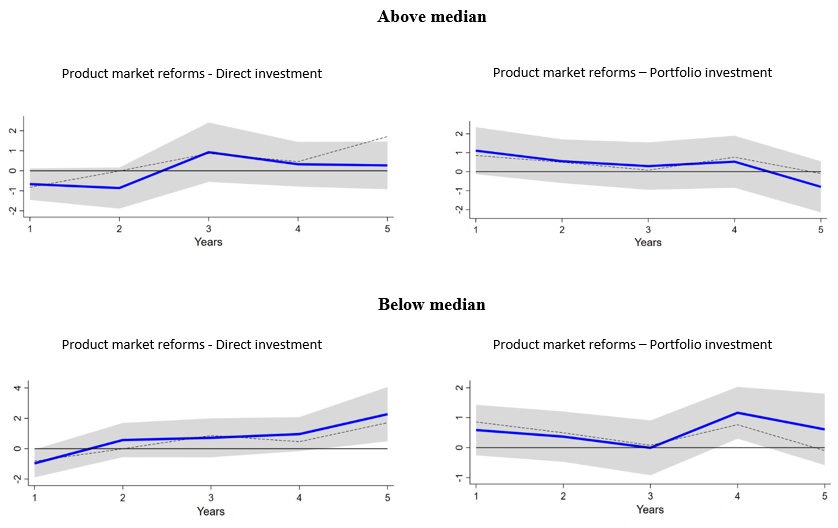

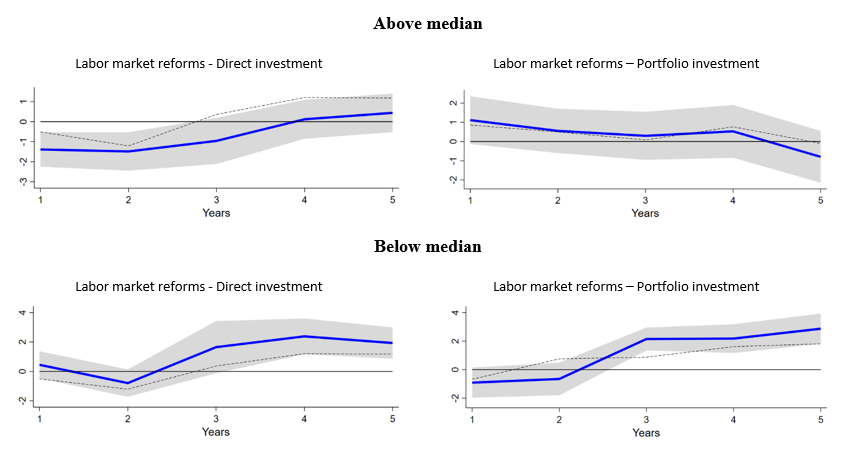

As reported in Figures 2 and 3 reforms in product and labor markets have a clear positive medium-term effect on direct and portfolio investment in cases of low public debt ratio, indicating that they function better when macroeconomic and fiscal conditions are sound (see e.g., Duval and Furceri, 2018). Note that the effects of reforms in a low debt environment are more pronounced relative to the baseline specification. Therefore, a low public debt ratio reflects stronger economic fundamentals, including stable fiscal positions, robust growth prospects, and effective governance, which can amplify the benefits of structural reforms. This aligns with Draghi (2024), who states that, in order for Europe to meet its investment objectives, it will be crucial to provide public support, implement fiscal incentives, and enhance productivity to stimulate private investment and ease the transitional fiscal burden. One possible policy instrument to achieve this is through structural reforms implemented within a better institutional framework and improved macroeconomic conditions.#f1

Figure 2. The effect of product market reforms on direct investments and portfolio investments in cases of above and below sample median public debt ratio.

Notes: The solid blue line represents the Average Treatment Effect (ATE) from the AIPW method of product market reforms in cases of above (upper panel) sample median and below (lower panel) sample median government debt. The dashed line illustrates the baseline ATE of product market reforms. The shaded area indicates the 90% confidence interval using bootstrapped standard errors.

Figure 3. The effect of labor market reforms on direct investments and portfolio investments in cases of above and below sample median public debt ratio.

Notes: The solid blue line represents the Average Treatment Effect (ATE) from the AIPW method of labor market reforms in cases of above (upper panel) sample median and below (lower panel) sample median government debt, as per model 2. The dash line illustrates the baseline ATE of labor market reforms. The shaded area indicates the 90% confidence interval using bootstrapped standard errors.

The findings of the study (for more details see Mavrogiannis and Tagkalakis, 2024), indicate that implementing product and labor market reforms has a positive effect on both direct and portfolio investment. Although these reforms initially have a negative impact on capital inflows, this effect becomes positive and statistically significant in the medium term. Moreover, reforms implemented in environments with stronger financial institutions and lower public debt levels tend to attract greater capital inflows. Thus, a sound macroeconomic environment, along with well-developed financial markets and institutions, enhances the effectiveness of these reforms, fostering competition in product markets and reducing regulation in labor markets.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: the origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Finance and Development-English Edition, 49(1), 53.

Alesina, A., Ardagna, S., Nicoletti, G., & Schiantarelli, F. (2005). Regulation and investment. Journal of the European Economic Association, 3(4), 791-825.

Blanchard, O., Ostry, J. D., Ghosh, A. R., & Chamon, M. (2016). Capital flows: expansionary or contractionary? American Economic Review, 106(5), 565-569.

Draghi, M. (2024). The future of European competitiveness – A competitiveness strategy for Europe.

Duval, R., & Furceri, D. (2018). The Effects of Labor and Product Market Reforms: The Role of Macroeconomic Conditions and Policies. IMF Economic Review, 66, 31–69. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41308-017-0045-1

End, N. (2024). Fueling or following growth? Causal effects of capital inflows on recipient economies. IMF Working Paper 24/15.

Gopinath, G., Kalemli-Özcan, Ş., Karabarbounis, L., & Villegas-Sanchez, C. (2017). Capital allocation and productivity in South Europe. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(4), 1915-1967.

Igan, D., Kutan, A. M., & Mirzaei, A. (2020). The real effects of capital inflows in emerging markets. Journal of Banking & Finance, 119, 105933.

López, G. G., & Stracca, L. (2021). Changing patterns of capital flows. BIS Committee on the Global Financial System Paper, (66).

Masuch, K., Anderton, R., Setzer, R., & Benalal, N. (2018). Structural policies in the euro area. ECB Occasional Paper Series, No. 210, June.

Mavrogiannis, C., & Tagkalakis, A. (2024). From Policy to Capital: Assessing the Impact of Structural Reforms on Gross Capital Inflows. Bank of Greece Working Paper No. 328. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4918687

Ning, L., & Wang, F. (2018). Does FDI bring environmental knowledge spillovers to developing countries? The role of the local industrial structure. Environmental and Resource Economics, 71(2), 381-405.

Ning, L., Guo, R., & Chen, K. (2023). Does FDI bring knowledge externalities for host country firms to develop complex technologies? The catalytic role of overseas returnee clustering structures. Research Policy, 52(6), 104767.

Ostry, J., Prati, A., & Spilimbergo, A. (2009). Structural Reforms and Economic Performance in Advanced and Developing Countries. IMF Occasional Papers. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781589068186.084.

Rodrik, D. (1996). Coordination failures and government policy: A model with applications to East Asia and Eastern Europe. Journal of International Economics, 40(1-2), 1-22.

see Mavrogiannis and Tagkalakis (2024) for the effect of reforms under high and low financial institution quality.