This SUERF policy brief is based on Chapter 3 of the ESM joint discussion paper with AMRO staff, “Geoeconomic fragmentation: Implications for the euro area and ASEAN+3 regions”. Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Pilar Castrillo, Nicola Giammarioli, and Rolf Strauch for their valuable comments and contributions to this policy brief, as well as colleagues from the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO) for valuable discussions, and Karol Siskind for the editorial review.

Abstract

As geopolitical tensions rise globally, the risk of geoeconomic fragmentation intensifies. The euro area’s financial links with countries whose foreign policies are now increasingly at odds with its own have grown over the past two decades. Therefore euro area capital flows may be exposed to geopolitical risks. While global uncertainty driven by geopolitical risks usually leads to increased inflows to the region, as investors seek safe havens, this dynamic is not guaranteed. If global tensions escalate, the euro area may experience capital outflows, raising risks to its external financing.

Geoeconomic fragmentation affects cross-border financing as well as international trade. Our recent ESM discussion paper examines the implications of fragmentation for external financing, taking a closer look at how the euro area’s cross-border investments are exposed to this evolving landscape.

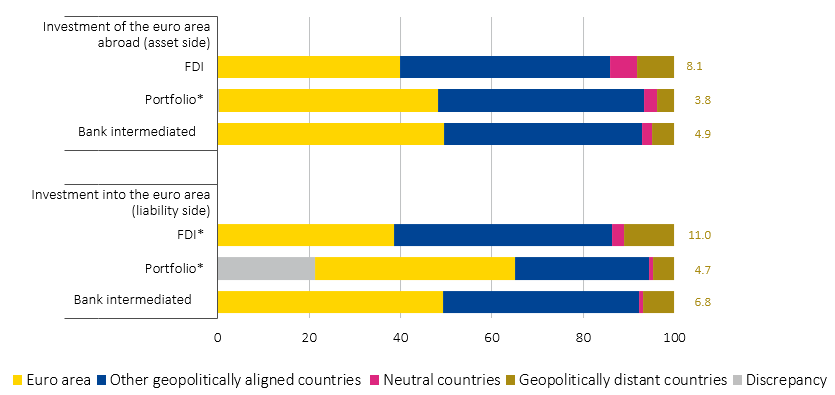

At first glance, the euro area may appear insulated from the risks of global financial fragmentation but does have pockets of vulnerabilities. Euro area countries’ external financial positions are mainly with other European Union Member States, and a large fraction outside the region is tied to other geopolitically aligned countries, notably the United States (US), the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Japan (see Figure 1a). Nonetheless, positions invested in and holdings from countries with divergent views on foreign policy issues, such as China, and Russia, are not trivial.

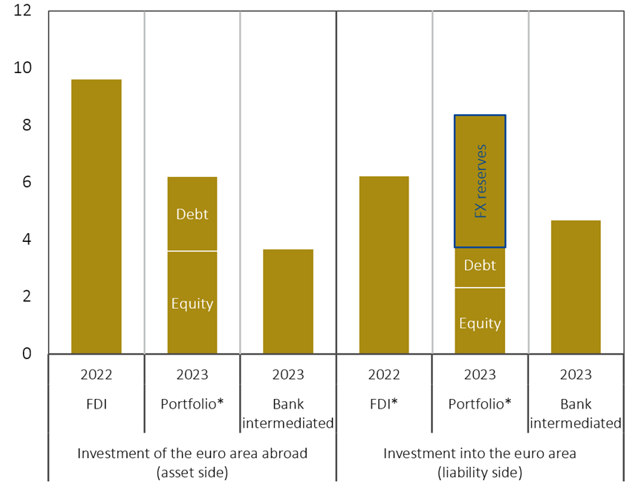

Comparing different types of financial exposures, foreign direct investment (FDI) and portfolio flows between the euro area and geopolitically distant countries stand out (see Figure 1b). Portfolio investment holdings from these distant countries into euro area securities reached 8.3% of GDP in 2023, including a significant portion of sovereign debt held as reserves by foreign central banks. Our estimates suggest that roughly one-third of euro area sovereign debt held by non-euro area investors is in the hands of non-politically aligned countries as official reserves, although this figure comes with high uncertainty due to data limitations.#f1

Figure 1. The euro area’s exposures to geopolitically distant countries are concentrated mainly in FDI and portfolio debt investment

1a. Euro area cross-border investment positions (latest, % of total)

1b. Euro area exposures to geopolitically distant countries (latest, % of euro area GDP)

Notes: Figure 1a plots the distribution of euro area countries’ cross-border asset and liability investment positions across stylised geopolitical groups based on United Nations General Assembly votes in 2022, as a proxy for geopolitical alignment. Figure 1b focuses on the euro area countries’ positions to the group of geopolitically distant countries relative to the size of the euro area economy. *Restated figures, wherein inward FDIs are estimated on an ultimate basis, and portfolio debt liability positions include securities held as reverse assets by foreign central banks (cf, “FX reserves”).

Source: ESM calculations based on the International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s Coordinated Direct Investment Survey and Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey, the Bank for International Settlement (BIS)’s Locational Banking Statistics, and other complementary data described in the ESM discussion paper.

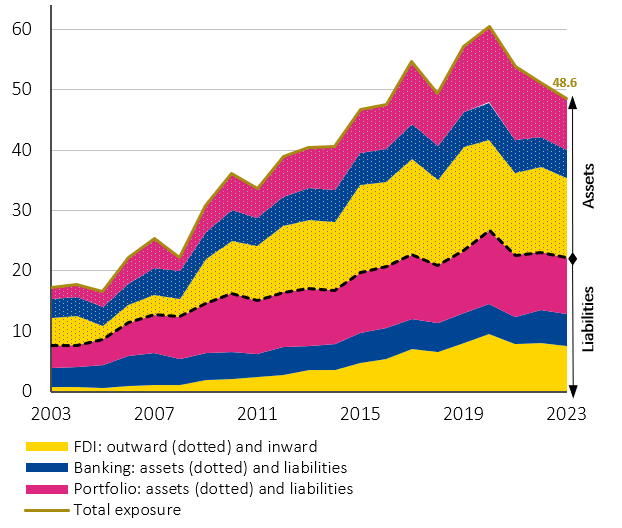

The past two decades have seen a sharp increase in the euro area’s gross financial exposure to the risk of geoeconomic fragmentation (see Figure 2). Summed across all financial instruments and directions, these “at-risk” positions more than doubled since 2008, peaking at 60% of euro area GDP in 2020. However, by mid-2023, they had fallen below 50%, indicating ongoing fragmentation. Recently, euro area investors have cut back on portfolio and FDI holdings in geopolitically distant countries, though some of these changes could be attributed to valuation effects.

Euro area member states are not equally vulnerable to the risk of geoeconomic fragmentation, given their varying degrees of openness, and different types of financial exposures. Inward portfolio investments to the euro area at risk generally exceed outward investments, particularly for euro area sovereigns whose debt is considered a “safe asset” and held as foreign exchange reserves by other countries. Large euro area countries also tend to have larger FDI investments in other countries that may be at risk. In contrast, smaller economies tend to have smaller direct exposures, mainly as recipients of inward FDI.

Figure 2. Euro area’s gross financial exposure to fragmentation risk (2003–2023, % of euro area GDP)

Notes: This figure plots the euro area’s estimated gross direct exposure to global financial fragmentation risk, decomposed by direction (assets versus liabilities) and type of cross-border instruments (FDI, portfolio investment and bank-intermediated investment). It is computed by weighting bilateral positions with a geopolitical proximity index (countries geopolitically aligned with China receive a weight of 1, neutral ones a weight of 0.5, and others a weight of 0). Gross positions (assets plus liabilities) are normalised by euro area GDP.

Source: ESM calculations based on the IMF’s Coordinated Direct Investment Survey and Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey, the BIS’s Locational Banking Statistics, and other complementary data described in the ESM discussion paper.

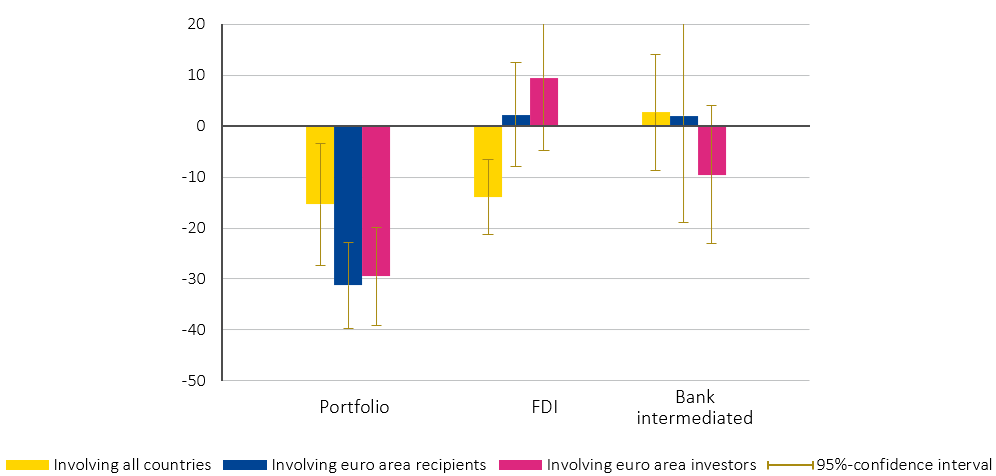

Geopolitical distance between two countries shapes their financial relationship. Empirical evidence confirms that investor countries allocate smaller investments to partners with differing foreign policy views. This sensitivity is particularly pronounced for portfolio investments to and from euro area member states (see Figure 3). If geopolitical distance between countries increases, it could lead to outflows from the euro area.#f2 Geopolitical factors can also play a role in the currency composition of foreign exchange reserves.3

Figure 3. Greater geopolitical distance leads to weaker financial ties between countries

(change in a partner’s investment share due to an increase in geopolitical distance, in %)

Adverse geopolitical events can also impact portfolio flows between the euro area and the rest of the world more broadly, as foreign investors’ behaviour towards the euro area can shift depending on the prevailing level of geopolitical risk. The period since the early 2000s has been characterised by long spells of low geopolitical tensions, punctuated by short episodes of heightened risk, but by the end of 2023 the world was in a high geopolitical risk regime.

The euro area is usually seen as safe haven, attracting net portfolio inflows. Our analysis shows that typically, when a geopolitical risk shock hits, euro area investors withdraw from foreign equities, while foreigners increase their purchases of euro area equities, resulting in net equity inflows. Additionally, the search for safety prompts inflows into euro area debt securities, as long as geopolitical risks are generally contained.

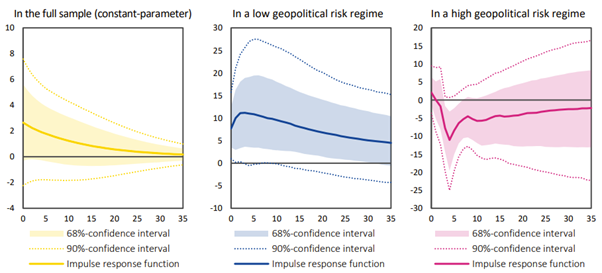

However, our findings also suggest that when geopolitical risks are more elevated, shocks can trigger portfolio outflows from the euro area, posing risks to the euro area’s external financing. This is especially the case for portfolio debt inflows, which are more fickle in a risky environment (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Elevated geopolitical risks can lead to portfolio outflows from the euro area

(impact of a global geopolitical risk shock on portfolio debt flows into the euro area as % of GDP)

Notes: Impulse responses to a one standard deviation shock to global geopolitical risk (Caldara and Iacoviello, 2022), based on a Bayesian vector autoregression (BVAR) model with monthly data from April 2000 to December 2023. The figure shows results from a constant-parameter BVAR model (i.e. normal times in yellow lines), and from an endogenous Markov regime-switching BVAR model that detects low risk (blue lines)/high risk (pink lines) regimes based on the level of the geopolitical risk index. A positive (negative) number indicates net purchases (sales) of euro area instruments by non-euro area investors.

Source: ESM calculations based on Eurostat, Haver analytics, and Caldara and Iacoviello (2022) data.

As geopolitical risks increase, financial shocks to the euro area may become more frequent and intense. The euro area’s response should not, however, amount to steps in the direction of isolation, as this would just reinforce global fragmentation.

The euro area stands to lose if globalisation reverses and global financial markets become fragmented, because financing could become more scarce and costly.

Instead of decoupling, a diversification of the euro area’s global financial linkages can help mitigate financial shocks. Domestically, risk-sharing through the help of the ESM, banking union, and savings and investment union would support the euro area’s resilience in the face of increasing global volatility.

Based on our estimates derived from a number of conservative assumptions, foreign central banks likely held in Q2 2023 at least €1.26 trillion in debt securities issued by eleven euro area sovereigns as part of their foreign exchange reserves. Around half of this amount is held by countries that are geopolitically distant from the euro area. To put this into perspective, the total marketable debt securities outstanding from these euro area sovereigns amounted to €10.3 trillion as of Q2 2023, and about €1.9 trillion is held by non-euro area residents. Foreign central banks from distant countries might represent only 6.2% of all investors in euro area sovereign debt, but they could account for a significant 33% of non-euro area investors.

According to our estimates, if less geopolitically aligned countries become even more distant, portfolio investments into the euro area could decline by 1.5% of euro area GDP – including 0.8% in equity and 0.7% in debt securities. Private portfolio flows are highly sensitive to geopolitical distance, but the potential outflows are moderate due to the relatively small exposures. Official reserve holdings are less sensitive to geopolitical shifts but the adverse impact on sovereign financing could be economically significant given the substantial size of these holdings. In the meantime, euro area investors could liquidate their portfolio claims in these distant countries by about 2.1% of euro area GDP.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that some central banks have recently diversified their reserve holdings away from geopolitically distant countries, and according to our analysis foreign reserves in euros may be more sensitive to geopolitical distance than reserves in US dollars. See also Chinn, Frankel and Ito (2024), “The dollar versus the euro as international reserve currencies,” Journal of International Money and Finance, 146, 103123; and Eichengreen, B., Mehl, A., & Chiţu, L. (2019), “Mars or Mercury? The geopolitics of international currency choice. Economic Policy, 34(98), 315-363.”