Abstract

Germany’s economy is facing significant challenges as it navigates global megatrends such as climate change, AI, and geopolitics. The traditional export-driven model is increasingly unsustainable due to protectionism, technological shifts, and costly energy transitions. Key reforms are needed in areas such as energy, labor markets, pensions, tax systems, and innovation. Germany must invest heavily in infrastructure and reduce regulatory burdens to maintain competitiveness. Strengthening European leadership and pursuing fair trade relations are also critical. A bold, future-oriented economic strategy – a “2030 Leitbild” – is necessary for Germany to overcome these hurdles, ensuring both national prosperity and its role in Europe’s future. “Business as usual” is not an option; bold, structural reforms are needed to unleash Germany’s potential for the future.

Over the past 25 years, megatrends such as demographics, climate change, AI and geopolitics have profoundly reshaped global economics. Poised at the crossroads of these transformations, Germany has slid into the second year of recession not only due to a temporary weakness but because of fundamental issues that raise doubts about its economic model. This situation is different from that of a quarter of a century ago, when Germany was considered the “sick man of Europe”. The solution then was relatively straightforward as the pillars of the German economic model – export-driven growth, industrial prowess and technology leadership – were unquestioned. A few (Hartz) reforms later, this model reliably delivered strong results again for years. Today, however, every single pillar of that model faces uncertainty: export orientation is reaching its limits in times of rising protectionism; engineering prowess is being eclipsed by the importance of data and software; technology leadership has eroded with dominance shifting to competitors from China and AI and industrial strength is under pressure from the costly energy transition. The German automotive industry epitomizes this perfect storm: tariff threats from the US, changing customer expectations for connected cars, a lag in electric vehicle technology, and enormous cost disadvantages in Germany as a business location.

To navigate these complexities, Germany needs a fresh start: a bold, future-oriented economic model that can continue the country’s success story. This requires a “2030 Leitbild” – a strategic vision that strengthens growth foundations and charts a path to future prosperity. This can only be achieved through the interaction of politics, business and science in order to develop a common understanding of the areas in which Germany should use its (limited) resources – and where it would be better to refrain from doing so. This strategic vision is needed as a compass to guide politics and the economy in an increasingly unpredictable world before questions on subsidies, new debt, tax and social cuts are even discussed. Ten key areas have emerged as crucial to reigniting Germany’s growth engine.

Germany needs substantial public investments. These are estimated at 9-18% of GDP over the next five to ten years, with a focus on energy, transport, education and defense. Closing this gap will require a comprehensive strategy that balances fiscal responsibility with the need for transformative investment to secure long-term growth. To do so, a reform of the debt brake towards a dynamic version and “golden rule plus” based on investments could be a way out. Raising the structural deficit ceiling to 1% of GDP creates room for investment spending while ensuring debt remains below 60% of GDP. Yet, structural reforms remain indispensible.

Short-sightedness has delayed Germany’s energy transition, leading to higher costs, slower decarbonization, and infrastructure development that lags the growth of renewable energy. To achieve long-term sustainability and also competitiveness, EUR 1 trillion of investment is needed by 2035, with equal shares going to modernizing energy infrastructure and expanding renewable energy capacity. It is a misconception that postponing or watering down the energy transition could help German industry. The opposite is the case: the costs of the restructuring would skyrocket and Germany would no longer be competitive with either old fossil fuel markets like the US or new green markets like Scandinavia or France (nuclear power!). “Stuck in the middle” is always the worst option. A headlong rush into the future is the only promising option.

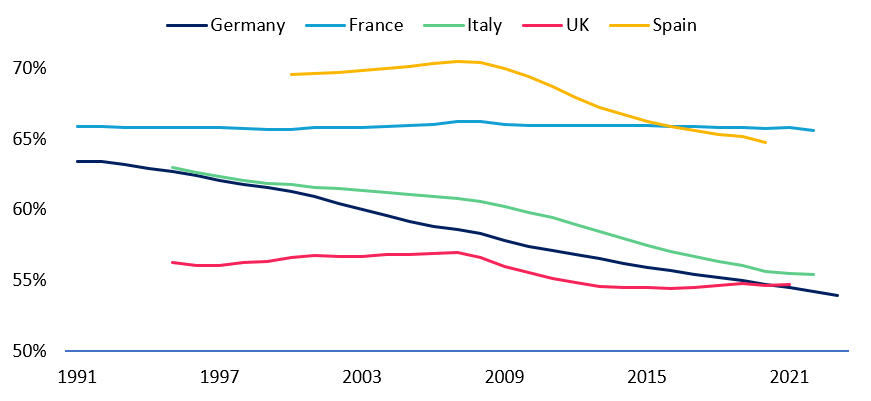

Public investment in Germany has fallen from 1% of GDP in the early 1990s to zero; as a result, the German capital stock has aged rapidly (Figure 1). The underinvestment has been particularly pronounced in public infrastructure – railways, highways, and waterways. The renewal of the capital stock will require an additional EUR 600 billion over the next decade – equivalent to 1.2% of GDP per year. To this end, public-private partnerships should be increasingly relied upon.

Figure 1. The aging of Germany’s capital stock, ratio of net to gross capital stock in %

Sources: OECD, Allianz Research.

Germany’s working-age population is projected to fall from 52 million to 43 million by 2050. Proactive labor market policies are needed to increase the workforce participation of women, older workers and immigrants. A two-pronged approach includes removing disincentives and barriers to working more and the creation of positive incentives. Disincentives include a lack of childcare options, tax regulations such as “Ehegattensplitting” (spousal income splitting) and retirement at 63; incentives include a reduction in the tax and contribution burdens as well as targeted skills training and language programs for immigrants. Furthermore, comprehensive education reforms are critical to lowering the share of young people leaving school without formal qualifications. As a benchmark, Germany could look to Sweden, where the labor force activity rates of women, foreigners, and older workers are significantly higher.

The old-age dependency ratio in Germany will increase from 34% to 51% by 2050. Pension policy must balance two competing objectives: ensuring a decent living standard in old age while avoiding an excessive burden on the working-age population. For the last two decades, pension policy has mainly focused on the first objective. This is no longer sustainable. From now on, costly measures such as the “Rentenpaket II” should be scrapped and capital-funded provisions such as “Riester II” and occupational pensions should be strengthened. Double taxation of retirement income must be avoided.

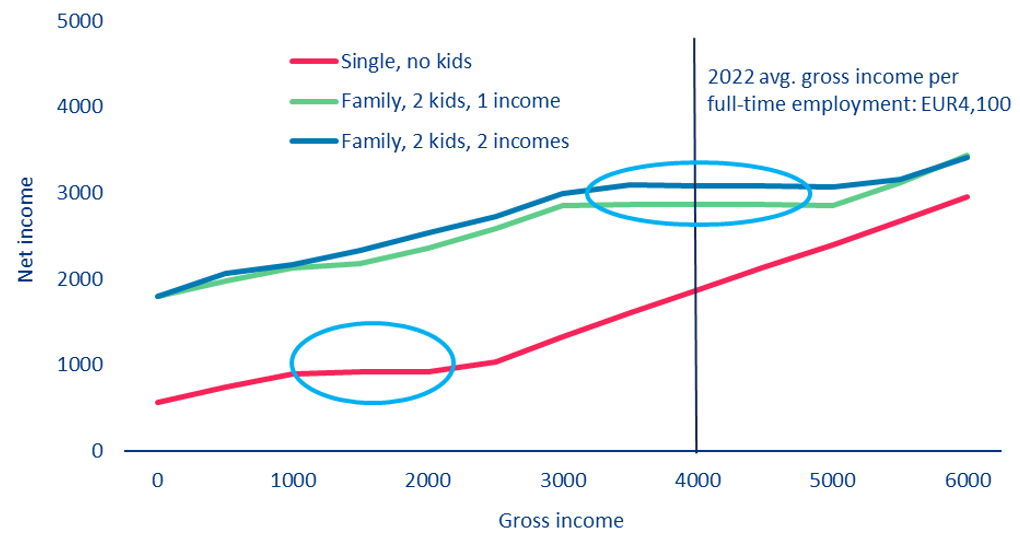

The current tax system in Germany places a heavy burden on the labor factor, with an effective income tax rate of 29% – compared to 19% in Italy or 15% in France. Moreover, it offers minimal incentives for low and middle-income earners to increase their gross income. For example, a married couple with two children whose monthly income increases from EUR 3,000 to EUR 5,000 – taking into account any social benefits such as housing assistance – would not see a single cent more in their wallets (Figure 2). A comprehensive reform of the income tax system, with a shift in the tax rates to higher income brackets, is therefore overdue. This would create more incentives to work and promote labor force participation.

Germany’s corporate tax rate is also relatively high at 29.9% with no major reform since 2008. Reforming this tax is politically challenging as it requires restructuring municipal finances. The trade tax could to be replaced with a corporate or income tax surcharge, ensuring municipalities maintain their revenue base. The corporate tax rate should be reduced to 25% and restrictions on loss offsetting need to be eased to improve business resilience during downturns and support growth and incentives to invest.

Figure 2. Comparison of monthly net and gross income (in EUR)

Sources: ifo Mikrosimulationsmodell, Destatis, Allianz Research.

Germany’s R&D investments of 3.1% of GDP are insufficient to claim leadership in future technologies such as AI, robotics, quantum or green technologies. Doubling R&D spending to 6% of GDP through tax breaks and strategic institutional support is essential for innovation and competitiveness. With its universities and institutions such as the Max Planck Institutes and the Fraunhofer Society, Germany has an excellent basis for promoting innovation, which it should make even greater use of in the future.

Despite progress, bureaucratic costs in Germany amount to EUR 146 billion per year in lost economic output; the direct costs are estimated by the Regulatory Control Council at EUR 65 billion. Reducing red tape by 25% over four years, digitalizing procedures and streamlining EU requirements are key to increasing efficiency and competitiveness.

A strong Franco-German partnership is vital for the EU’s success, yet, in recent years this partnership has faltered. The new EU Commission and a new German government offer a chance for a fresh start (although France’s role is likely to remain uncertain due to ongoing political instability). Germany must constructively advance two crucial EU issues: the question of common debt and the completion of the Capital Markets Union (CMU). Germany’s traditional resistance to common debt is no longer appropriate in view of the enormous defense efforts that Europe must undertake. Common debt can serve as a lever to establish common military spending by the EU within NATO and to promote the integration of the European defense industry. This instrument is also suitable for a common European energy market.

Completing the CMU, on the other hand, is essential to boost the EU’s competitiveness by opening up more financing options for companies. The focus should be on revitalizing EU equity markets, particularly venture capital (VC) and private equity (PE) – Europe lags far behind the US. To achieve this, savings and investment behavior must be realigned. To this end, strengthening funded pensions to redirect institutional investors to equities and incentives such as tax breaks to encourage private savers to invest in equity markets are crucial. The potential in Germany alone is huge. German households have financial assets of EUR 9 trillion (September 2024). The share of bank deposits at 41% (end of 2023) is significantly higher than in France (30%) and Italy (28%). If German households were to reduce their share of deposits to 30% over the next ten years, they could “free up” at least EUR 80 billion per year. In addition, German households are expected to have acquired financial assets worth EUR 300 billion in 2024; half of this is likely to flow into bank deposits. Reducing the share of banks in fresh savings to 30% could free up an additional EUR 60 billion for long-term savings and green investments. This simple calculation shows that German households have the potential to invest at least EUR 100 billion annually in capital market products.

Germany’s export-led model, with exports accounting for 43% of GDP, is under strain as globalization wanes. Exports to China have already been declining for several years and those to the US are likely to follow in view of tariff threats. Germany must therefore align its value chains more consistently with Europe, push for free trade agreements and advocate for a common European industrial policy.

For Germany, “business as usual” with incremental reforms will thus not be enough. Like its cars, Germany needs a revolutionary software update to position its economy for a new era of much-needed growth. This is very important, not only for Germany itself, but because a weak Germany will drag Europe down with it – and a weak Europe is the last thing the liberal world can afford right now.