The health crisis has severely impacted global trade and revived debates about the location of production. The widespread onshoring of manufacturing activities would mean abandoning the gains from international specialisation, but without necessarily making value chains more resilient. French companies, as their European counterparts, mainly source their inputs from another European countries and thus a coordinated, EU-wide economic policy response is the way to go.

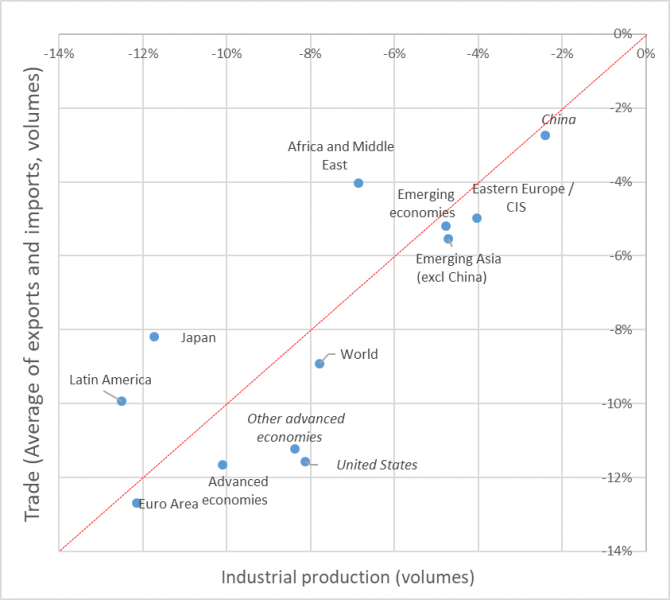

Chart 1: Percentage change in volumes of manufacturing output and external trade between

January-June 2019 and January-June 2020

Source: CPB World Trade Monitor. Authors’ calculations.

Note: Between the first semester of 2019 and the semester of 2020, Euro-area manufacturing output (x-axis; member countries are trade-weighted) declined by 12.2 percent, while trade (y-axis, the geometric mean of export and import growth) fell by about 12.7 percent. The point representing the Euro area is close to the red bisector.

The Covid-19 crisis has had a severe impact on world trade. According to CPB data, measured in volumes, trade flows plunged by 11% between December 2019 and June 2020. This decline is closely linked to the fall in manufacturing output. Chart 1, compares the evolution of external trade and of manufacturing output and clearly shows that the adjustment in both cases is very close to the 45 degree line. There is nonetheless some heterogeneity across regions, which can be explained by the geographical spread of the epidemic and by differences in the health measures adopted in response. In addition to the direct effects of the health crisis on output, world trade may have amplified the spread of the economic shock between countries via deliveries to (supply shock) or imports by (demand shock) trading partners.

To understand how shocks linked to Covid-19 are transmitted through international trade linkages, we need to take account of the central role played by global value chains (GVCs), which are defined as production processes that are dispersed geographically and thus cover several countries. This international fragmentation of production chains, which intensified in the 1990s, has contributed to the rise in world trade over the past 30 years. Such impressive development has been made possible by technological advances, especially those linked to information and communication technology (ICT), and by the signature of numerous trade agreements, which have significantly reduced barriers to world trade.

Richard Baldwin shows fragmentation can be observed in all stages of the manufacturing process (research and development, design, manufacture of intermediate goods, assembly, marketing, distribution). For example, Boeing works with suppliers in around 150 countries, while Apple’s iPhone incorporates factors of production from around 50 countries spread across five continents. All sectors are affected by the internationalisation of production, either directly or indirectly.

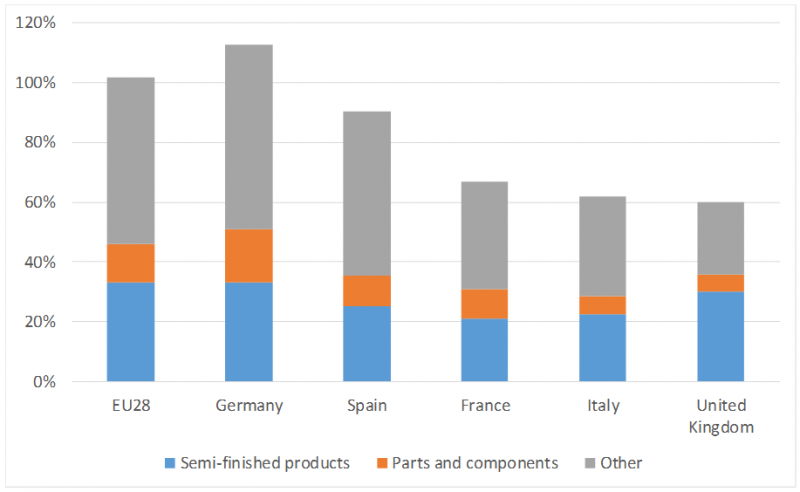

Chart 2 shows that over the period 2002-2019, imports of parts and components and of semi-finished products used in manufacturing accounted for nearly half of the import growth in European Union countries. Gaulier, Sztulman and Ünal (2020) show that the Great Recession of 2008-09 did not slow the development of GVCs.

Chart 2: Import growth in EU countries (2002-2019), by type of good

Source: Eurostat-Comext value data by production stage (BEC), and authors’ calculations.

Key: In the case of Germany, semi-finished products (in blue) account for 33% of the growth in total imports, whereas parts and components (orange) account for 17%. When the contribution of other goods (shown in grey) is included, growth in total goods imports over the period 2002-19 is 113%.

The specialisation of individual economies in their comparative advantage sectors, and the international fragmentation of production across different segments of the value chain, have helped make production more efficient at the global level. As a consequence a company’s competitiveness no longer relies solely on its own productivity, but also on its ability to source supplies from most efficient companies.

The fragmentation of production can nonetheless create vulnerabilities in the event of the failure of partner firms upstream or downstream in the value chain. For example, the introduction of restrictions to stop the spread of the pandemic led to disruptions in supply. Moreover, the transport and distribution difficulties caused by the lockdowns also had knock-on effects upstream and downstream in value chains.

The Covid-19 crisis has renewed the debate over the location of production, and increased the temptation to shift all or part of value chains back onto domestic territory in order to insulate them from shocks originating in other countries, and thereby “safeguard” them in the event of another crisis.

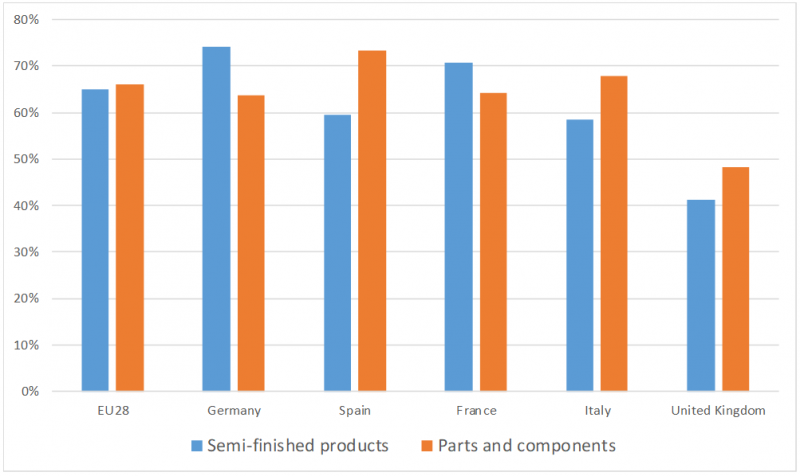

Yet value chains tend to be more regional than global in nature. Chart 3 shows that, in European countries, the vast majority of the intermediate goods used in manufacturing are sourced from other EU Member States. This regional concentration of production can first be explained by geography, which traditionally plays a very strong role in determining the intensity of trade flows between partner countries. However, it is also attributable to economic and integration policies, which have enabled Europe to create a stable environment that is favourable for trade ties, notably the single market and common currency.

Chart 3: Share of the EU (28 members) in imports of intermediate goods

Source: Eurostat-Comext value data by stage of production (BEC) (2019), and authors’ calculations.

This observation provides a first response to possible tensions in value chains, and to the challenges of onshoring: since French firms’ international supply chains are primarily European, an EU-level coordinated economic policy response is the appropriate course of action.

It would also be useful to hold an overall reflection on how value chains function within different sectors. Although it is indeed legitimate to want to safeguard supplies of certain “strategic” products, such as those linked to health care, as highlighted in the public debate, it is important that this reflection does not underestimate the productivity gains linked to specialisation, or ignore the benefits of the international diversification of supply sources. Heise (2020), for example, shows that US firms that had pre-established ties with Vietnam were able to secure supplies that had previously been sourced from China. Increased diversification of supply sources would ensure greater resilience in the event of future crises.