This policy brief is based on IMF Working Papers 24/125. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

Abstract

We argue that ‘green’ fiscal rules (that exempt green-related spending or borrowing from fiscal rule limits) are not an effective tool for fiscal policy to tackle climate change. In addition to other practical design challenges, simple simulations of green rules illustrate that they can either (i) lead to unsustainable debt dynamics when climate goals are pursued mostly using spending-based instruments (e.g., public investment and subsidies), or (ii) need to implicitly assume an overly large fiscal adjustment in the non-green budget, which would undermine the rule’s credibility. Another caveat is the high uncertainty surrounding countries’ climate cost estimates. A better alternative is adopting a more comprehensive strategy to integrate climate change considerations into fiscal policy design, taking into account the complex policy trade-offs and long-term effects. The appropriate mix of climate policies, including carbon pricing, should be pursued within the overall setting of fiscal and debt objectives. Developing ‘green’ medium-term fiscal frameworks would help design appropriate policies and build public consensus for the needed climate reforms.

Addressing climate change will require significant upfront action by governments, together with the private sector, on mitigation and adaptation. The impact of such actions on the fiscal accounts can vary widely depending on the tools chosen and the country specificities (including the degree of vulnerability to natural disasters). For instance, relying largely on expenditure-based measures to achieve net zero emissions would put significant pressure in the fiscal accounts in the absence of compensatory measures on the revenue side (IMF October 2023 Fiscal Monitor).

Some have suggested the introduction of so-called ‘green’ fiscal rules – which typically propose excluding spending (and borrowing) associated with green policies from fiscal rule limits – as a solution to both protect climate-related priorities and promote fiscal sustainability (e.g., Darvas and Wolff, 2021). Other variants include modifying rules to include ‘green’ escape clauses, setting benchmarks to guarantee a minimum level of expenditures, or the establishment of green investments funds towards achieving climate goals.

Yet, green fiscal rules suffer from severe design challenges, prompting the need for a more comprehensive fiscal strategy to tackle climate change, as described in the remainder of this note.

Fiscal rules, whether green or not, should be calibrated to meet their central objective of promoting debt sustainability. This requires that the level of spending is consistent with the level of revenue mobilization and a manageable debt level under most economic scenarios. However, the fiscal costs associated with addressing climate change are highly uncertain and potentially very high, especially if countries rely mainly on government spending measures (e.g., investment, subsidies). Excluding such fiscal costs from fiscal rules (including limits on borrowing) could lead to disruptive debt dynamics and undermine the effectiveness of the fiscal rules in promoting fiscal discipline and ultimately the ability of the government to deliver on its development and green goals.

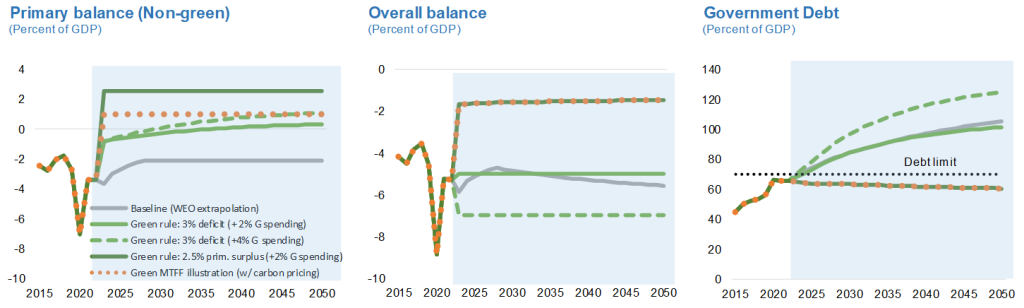

For illustration, we simulate the impact of simple green rules on fiscal balances and debt for a typical emerging market (EM). We follow a methodology for calibrating traditional fiscal rules that has been widely applied. Simply put, fiscal rules should safeguard that public debt remain below a threshold (debt limit), above which debt sustainability risks are high (and lead to debt distress). Caselli and others (2022) estimate that for a typical emerging market the debt limit was around 95 percent of GDP pre-pandemic (when global interest rates were low) but was significantly lower at around 70 percent of GDP during the mid-2000s; the lower end of this 70-95 range can be considered a prudent limit. Next, using the IMF’s FAD debt anchor calibration toolkits (Eyraud and others, 2018; Gbohoui and others, 2023), we estimate that debt should target additional fiscal buffers (a safety margin below the debt limit) of around 20 percent of GDP when accounting for normal macroeconomic volatility and up to 30 percent of GDP when also accounting for tail risks from natural disasters. In other words, according to this simplistic calibration, a typical EM may want to avoid public debt exceeding 70 percent of GDP and target levels below 40-50 percent of GDP over the medium term to ensure public debt sustainability.

Finally, we simulate fiscal balance and debt trajectories, following Escolano (2010), under alternative green fiscal rules. We abstract from modeling the energy transition and assume, in all scenarios, that the representative EM reaches a net zero emissions goal by 2060 by adopting mostly spending-based policies (such as public investment and subsidies, with limited use of carbon pricing), requiring additional expenditures of around 2 percent of GDP per year relative to baseline investment (October 2023 Fiscal Monitor). Moreover, beyond investment needs for mitigation, building resilience to climate change would imply further climate-change adaptation costs averaging around 1-2 percent of GDP per year for many developing countries (Aligishiev et al. 2022). Noteworthily, these estimates are highly uncertain and subject to wide dispersion across countries, which further complicates the calibration of green fiscal rules.

Our simulations show that, since the fiscal costs of green policies can be very large, debt can either become unsustainable or overly compress other spending under a green rule, resulting in an inefficient allocation and undermining the fiscal rule (Figure 1).

In particular:

Figure 1. Typical EM: Green Fiscal Rules Could Lead to Unsustainable Debt Levels or Overly Tight (Non-Green) Fiscal Balances

Further challenges in designing green fiscal rules

Green fiscal rules also face other operational challenges related to their design. For instance:

Given the significant tradeoffs involved, a broader policy analysis and discussion is needed. Such efforts will require building wide public support for the difficult policy choices and a more comprehensive fiscal strategy. Most countries will need to adopt a mix of policies and tools to share the burden of the climate transition between the public and private sector. It will likely involve to some degree carbon taxes, public and private investment, regulations on energy efficiency and climate adaptation. Such complex and dynamic policy choices cannot feasibly be reflected in a fiscal rule.

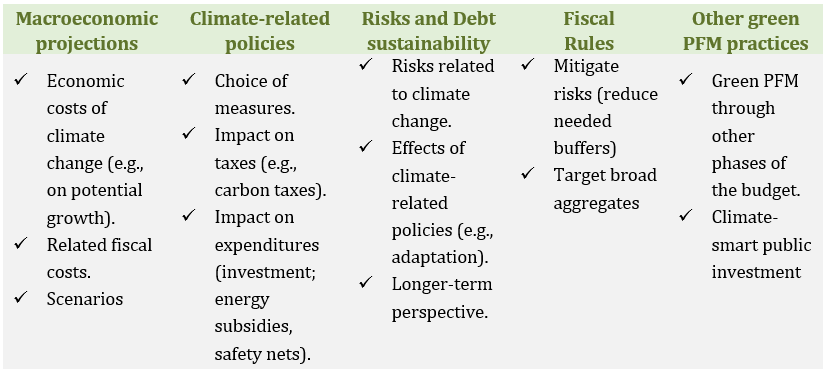

Instead of green rules, we propose a more comprehensive method of incorporating complex climate considerations in the formulation of fiscal policy using medium-term fiscal frameworks– an important tool to guide and articulate governments’ medium-term fiscal plans. MTFFs comprise a set of institutional arrangements for prioritizing, presenting, reporting, and managing fiscal aggregates; they include a fiscal strategy and medium-term projections of macro-fiscal aggregates, in which outer year budget ceilings can help to guide subsequent annual budgets.

Adopting ‘green’ MTFFs—that account for the (long-term) effects of climate change and climate policies on fiscal accounts—can help optimize the mix of green fiscal policy tools. We propose the following main elements for an effective green MTFF (Figure 2):

Figure 2. Components or Elements Supportive of Green MTFFs

Making economies greener and more resilient to natural disasters is of paramount importance. Governments will need to play a leading role, but the fiscal costs could be significant and will require addressing complex tradeoffs. Governments are debating ways to protect climate-related spending amidst tight budget constraints and rising debt sustainability concerns, but green fiscal rules are not an effective solution. Fiscal rules are not a panacea—their primary objective should be to constrain excessive deficits and signal commitment to fiscal responsibility. Excluding ‘green’ spending from the rule limits would undermine those objectives and ultimately constrain governments’ ability to pursue its policy priorities, including on climate. An alternative, more comprehensive, approach is to strengthen medium-term fiscal frameworks to better reflect the challenges posed by climate change and the effects of green policies.

Aligishiev, Z., M. Bellon, and E. Massetti. 2022. “Macro-Fiscal Implications of Adaptation to Climate Change”, IMF Staff Climate Note 2022/002, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Caselli, F., H. Davoodi, C. Goncalves, G. H. Hong, A. Lagerborg, P. Medas, A. D. M. Nguyen, and J. Yoo. 2022. “The Return to Fiscal Rules,” IMF Staff Discussion Note No. 2/22, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Darvas, Z., and G. Wolff. 2021. “A Green Fiscal Pact: Climate Investment in Times of Budget Consolidation.” Policy Contribution 18/2021, Bruegel.

Escolano, J. 2010. “A Practical Guide to Public Debt Dynamics, Fiscal Sustainability, and Cyclical Adjustment of Budgetary Aggregates“, IMF Technical Noes and Manuals.

Eyraud, L, Debrun, X., Hodge, A., Lledo, V., and Pattillo, C. 2018. “Second-Generation Fiscal Rules: Balancing Simplicity, Flexibility, and Enforceability”, IMF Staff Discussion Notes No. 18/04.

Gbohoui, W., O. Akanbi, and W. R. Lam. 2023. “Calibrating Fiscal Rules: A Consideration of Natural Disaster Risks,” January 2023, International Monetary Fund, Washington, D.C.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2023. “Fiscal Monitor: Climate Crossroads: Fiscal Policies in a Warming World,” Washington, DC, October.

Mancini, A. L. and P. Tommasino. 2023. “Fiscal Rules and the Reliability of Public Investment Plans: Evidence from Local Governments”.

Mian, A., L. Straub, and A. Sufi. 2022. “A Goldilocks Theory of Fiscal Deficits”, NBER Working Papers 29707, National Bureau of Economic Research.