References

Alfaro, L. and D. Chor (2023): “Global Supply Chains: The Looming ‘Great Reallocation’” Working Paper 31661, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Antras, P. (2020): “De-Globalisation? Global Value Chains in the Post-COVID-19 Age”, Working Paper 28115, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bailey, M. A., A. Strezhnev, and E. Voeten (2017): “Estimating Dynamic State Preferences from United Nations Voting Data”, Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61, 430–456.

Desai, M. A., C. F. Foley, and J. R. Hines (2009): “Domestic Effects of the Foreign Activities of US Multinationals”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 1, 181–203.

Gong, H., R. Hassink, C. Foster, M. Hess, and H. Garretsen (2022): “Globalisation in reverse?

Reconfiguring the geographies of value chains and production networks”, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 15, 165–181.

Kovak, B. K., L. Oldenski, and N. Sly (2021): “The Labor Market Effects of Offshoring by U.S. Multinational Firms”, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 103, 381–396.

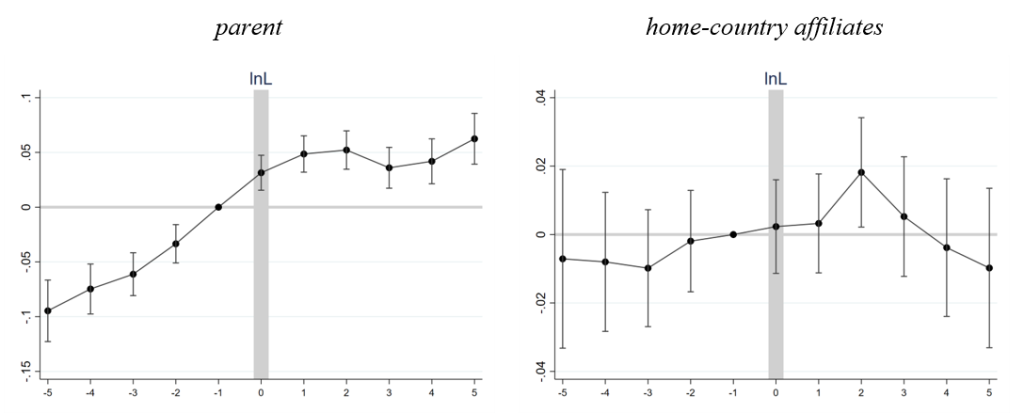

Merlevede, B. and B. Michel (2024): “Home Country Effects of Multinational Network Restructuring in Times of Deglobalisation: Evidence for European MNEs”, Working Paper 465, National Bank of Belgium

Merlevede, B. and A. Theodorakopoulos (2024): “The Margins of Ownership Structures – Insights from 145,000 Networks over 25 years”, mimeo, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Ghent University, Belgium.

Miroudot, S. and D. Rigo (2022): “Multinational Production and Investment Provisions in Preferential Trade Agreements”, Journal of Economic Geography, 22, 1275–1308.

UNCTAD (2013): Global Value Chains: Investment and Trade for Development, World Investment Report.

UNCTAD (2020): International production: a decade of transformation ahead, Chapter IV in World Investment Report.

Yamashita, N. and K. Fukao (2010): “Expansion abroad and jobs at home: Evidence from Japanese multinational enterprises”, Japan and the World Economy, 22, 88–97.