Gabriele Galati and Maarten van Rooij, De Nederlandsche Bank; Richhild Moessner, Bank for International Settlements and CESifo – The opinions in this Policy Brief are the authors’ own opinions, and do not necessarily coincide with those from the BIS or DNB.

Inflation expectations and their anchoring has come further into the spotlight as global inflation has been persistently high since mid-2021. In the euro area, headline inflation reached 8.9% in July 2022, the highest figure since the creation of the euro. High inflation has initially been explained mainly by supply factors, such as supply bottlenecks related to the Covid-19 pandemic. However, continuing upside surprises of inflation data and evidence from sectoral data that high inflation has become more broad based, have led to raising concerns about a de-anchoring of inflation expectations on the upside (BIS, 2022).

When monitoring inflation expectations, central banks have increasingly turned their focus on expectations held by households and firms. Following results from the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers published on 15 July 2022, which showed a drop in US households’ inflation expectations, press reports and market commentary expected the Federal Reserve to tighten less at its next FOMC meeting.1

In parallel, a growing research literature has documented the importance of household expectations and their different properties compared to expectations by financial markets and professional forecasters.2

There is still little evidence on the anchoring of consumers’ long-term inflation expectations, particularly in the euro area, since most available surveys of households provide information only on short-term inflation expectations, while long-term expectations are crucial for anchoring.3

A monthly satellite survey of the DNB Household Survey on Dutch consumers’ inflation expectations, which has been conducted since December 2019, sheds light on the anchoring of households’ inflation expectations in an environment of persistently high inflation.4 In the satellite survey, half of respondents receive information about the ECB’s inflation target and realised inflation. In analysing this survey, we focus on the effect of the strong rise in inflation that started in August 2021.

We investigate anchored inflation expectations in two ways, i.e. in the sense of ‘level anchoring’ and in the sense of ‘shock anchoring’. According to the level anchoring definition, long-term inflation expectations are well anchored if they are tied to the target of monetary policymakers (see e.g. Grishchenko et al., 2019). Anchoring can be assessed by looking at the median (or mean) of consumers’ long-term inflation expectations or the whole distribution of these expectations. We measure level anchoring in terms of the deviation of the median level of long-term inflation expectations from the ECB’s symmetric inflation target of 2%. In addition, we look at the expected probability of inflation being close to target ten years ahead, and examine whether during the period of high inflation, households’ expected probabilities of inflation being 4% or higher have increased.

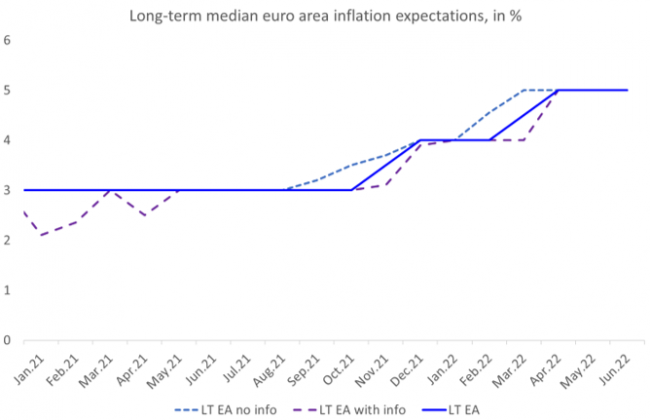

Three important results emerge from our empirical analysis on level anchoring. First, median euro area expectations have risen since the strong increase in inflation above target, both for short- and long-term expectations (Figure 1 shows the increase for long-term inflation expectations).

Figure 1: Dutch households’ long-term median euro area inflation expectations

Source: DHS satellite survey.

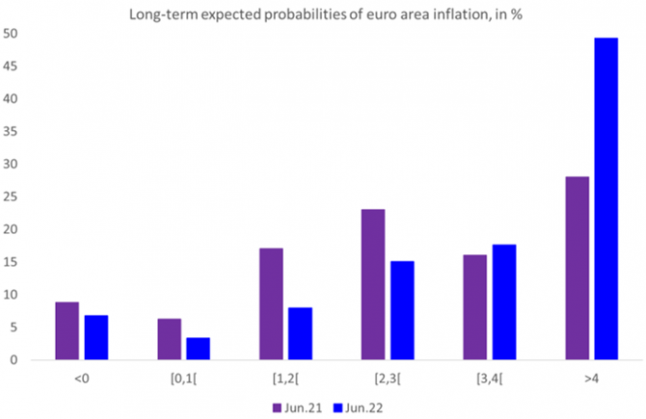

Second, as euro area HICP inflation has been consistently above the ECB’s target, households’ expected probabilities of high inflation (4% or higher) have increased since mid-2021, both for the short- and long-term horizons. Consumers’ long-term expected probabilities of high inflation have increased by 21pp over this period (Figure 2).

Third, median long-term expectations of households who received information about current and past inflation as well as the new ECB’s inflation target, have risen, and by the same amount as the expectations of households who did not receive that information (Figure 1). As shown in Galati et al. (2022b), median short-term expectations of households who received information about current and past inflation and the new ECB’s inflation target have risen as well, and slightly more than the expectations of households who did not receive that information. The fact that inflation expectations have clearly risen for those who received and those who did not receive information suggests that Dutch households’ elevated and rising inflation expectations cannot be explained only by possible misperceptions of actual inflation or the ECB’s inflation aim.

Figure 2: Dutch households’ long-term expected probabilities of euro area inflation

Source: DHS satellite survey.

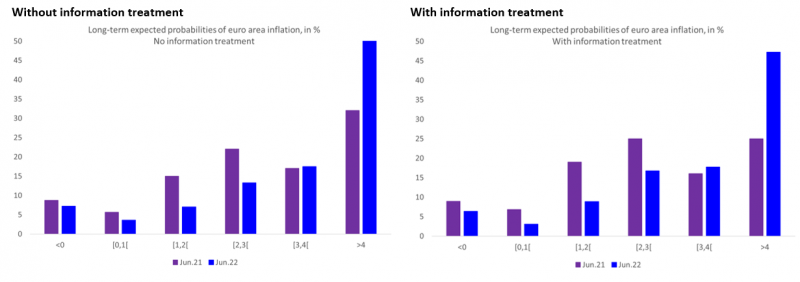

According to the shock anchoring definition, long-term inflation expectations are well anchored if shocks to inflation or to short-term inflation expectations are not passed into long-term inflation expectations (see e.g. Ball and Mazumder, 2011 or Galati et al., 2022a). Figure 2 shows how the strong increase in inflation led Dutch households to revise their long-term expectations of euro area inflation upward. Also, the average probability of high long-term inflation (i.e. a 10-year ahead inflation rate of 4% or more) increased considerably during the last 12 months. This is the case for respondents who did and for respondents who did not receive information on the ECB’s inflation target and on current and past inflation developments (Figure 3). These results highlight that long-term inflation expectations are not insensitive to shocks in realized inflation as the one we are experiencing now.

Figure 3: Dutch households’ long-term expected probabilities of euro area inflation, by information treatment

Source: DHS satellite survey.

Overall, the results suggest that long-term euro area inflation expectations of households have become less well anchored since inflation has increased strongly above target since mid-2021. The expectations both of the group who received information and of the group who did not receive information became less well anchored in the period of actual inflation rising strongly above target.

In the current environment of persistently high inflation, there are increasing concerns that inflation expectations have de-anchored in the euro area on the upside, above the ECB’s inflation target. This could weaken the monetary transmission mechanism and threaten price stability. Our results, which are based on data from a survey of Dutch households, suggest that since mid-2021 consumers have been increasingly concerned about inflation rising significantly above the ECB’s inflation aim.

Ball, L. and S. Mazumder (2011). Inflation dynamics and the Great Recession, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring, 311-405.

Bank for International Settlements (2022). Annual Economic Report. Chapter I: Old challenges, new shocks.

Bottone, M., , A. Tagliabracci and G. Zevi (2021). Inflation expectations and the ECB’s perceived inflation objective: novel evidence from firm-level data. Banca d’Italia Occasional Papers No.621, June.

European Central Bank (2021). ECB’s Governing Council approves its new monetary policy strategy, press release, 8 July.

Galati, G., Moessner, R. and M. van Rooij (2022a). The anchoring of long-term inflation expectations of consumers: insights from a new survey. Oxford Economic Papers, gpac005.

Galati, G., Moessner, R. and M. van Rooij (2022b). Reactions of household inflation expectations to a symmetric inflation target and high inflation, DNB Working Paper No. 743.

Grishchenko, O., Mouabbi, S. and J.-P. Renne (2019). Measuring inflation anchoring and uncertainty: A U.S. and euro area comparison. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 51.

Hilscher, J., A. Raviv and R. Reis (2022) How likely is an inflation disaster?. CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP17224.

Reis, R. (2021). The People versus the Markets: A Parsimonious Model of Inflation Expectations, CEPR Discussion Papers 15624.

Reis, R. (2022). Losing the Inflation Anchor, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity Conference Drafts, 9 September.

Smith, C. (2022). US inflation expectations survey eases fears of 1% rate rise from Fed. Financial Times, 13 July.

See Smith (2022).

See e.g. Reis (2021, 2022) and Hilscher et al. (2022).

There are even fewer studies of surveys of inflation expectations held by firms in the euro area. One exception is Bottone et al. (2021), who analyze the Bank of Italy’s quarterly Survey on Inflation and Growth Expectation and find that Italian firms’ expectations were well anchored to the ECB’s inflation target.

See Galati et al. (2022b).