As many European Member States are adopting new measures to green their economy and support the ecological transition, consistency of budgetary policies with environmental goals is not yet ensured. At times, budgetary policies targeting environmental protection coexist with measures that are unfavourable to the environment. In addition, an overall understanding of how a country’s budget affects the environment is often missing. Through a screening of budgetary documents across the EU, this note describes approaches used to present the environmental implications of national budgets and of the EU budget. Overall, only few Member States and the EU explicitly present information on the extent their budgets (or parts of them) are aligned with environmental goals. When these practices exist, they differ substantially, particularly with respect to the methodology, the coverage of budgetary items and environmental objectives, the governance and transparency setting. This heterogeneity is partly explained by different underlying definitions of environmental objectives and budgets’ contribution towards them. The note also defines concepts related to green budgeting, and provides an insight on recently established ‘environmental watchdogs’.

Several approaches exist to assess the greenness of budgetary items. In some cases, such assessment consists in ‘tagging’ the environmental content of a specific budgetary item; in other cases, it consists in a fully-fledged impact assessment analysis; and at times, it entails identifying only those items for which the environment is a main purpose. These different approaches reflect the various facets of the ‘greenness’ concept, which could alternatively be considered in terms of impact, contribution or (main) purpose. While impact refers to the quantifiable effect (estimated or calculated) that a policy has on a specific environmental indicator (i.e., CO2 emissions), a contribution captures a prediction of the effect without quantification (i.e., the positive expected contribution of a tobacco tax on air quality). Finally, the main purpose of a budgetary item, instead, identifies the overriding reason underpinning that item. For example, a fuel tax has an environmental purpose, as well as an environmental contribution and an expected impact. However, a tax on cigarettes has health as main purpose but contributes to the environment with a specific impact, as it reduces pollution from smoke and cigarette-related waste.

As impact assessment analyses may not always be feasible, due to lack of time and resources or lack of traceable indicators, contributions could be more easily captured. Also compared to an approach focused on the main purpose, assessing a contribution would better capture the environmental content of an expenditure or revenue item in its different nuances. To assess contributions, countries tend to use a tagging methodology.

A few tagging approaches are available. Drawing on the work done within development assistance aid, a ‘Rio markers’ system has been developed which assigns three possible values to a measure, indicating whether climate or environmental objectives are (0) not targeted, (1) a significant objective or (2) a principal objective of the action in question. Depending on the value attributed, the following percentages are at times used 0%, 40% and 100%, respectively. In other contexts, more specific percentages can be applied, corresponding to the content of the item that is defined green or, alternatively, a binary approach is used, where the entire cost of the expenditure item is considered green or not green.

Capturing the environmental contribution of a specific budgetary item is a challenging task for a number of reasons. Firstly, as the environmental objective encompasses a variety of goals, ranging from climate change mitigation to biodiversity and landscape protection, specific budgetary measure could contribute to several of such goals at the same time, and at times with opposite signs (i.e., public investment in wind farms is favourable for climate but unfavourable for biodiversity). Secondly, a contribution could take place after direct and less direct rounds of effects. For example, a fiscal benefit encouraging teleworking patterns might ultimately have positive effects on air quality. Thirdly, a contribution can be ‘more’ or ‘less’ green compared to others, as budgetary measures exert environmental pressures to different degrees. For example, the effect of a scheme for electric vehicles can be less green than spending in energy efficiency renovations. Fourthly, a measure could display different ‘shades of green’, as some measures can be fully green, or slightly green. For example, energy efficiency renovations of buildings are not fully green items as some aspects of the renovations, such as the use of primary materials, may be environmentally harmful. Finally, environmental objectives can have moving targets as countries improve their green performance. For example, the use of some specific bio-fuels that have to be combined with fossil fuels to be viable, would be deemed green in the current context but not in the future as it does not contribute to a zero net-emission target.

Selected evidence in the EU

A screening of budgetary documents reveals that only few Member States and the EU explicitly present information on the greenness of their budgets. Most of these practices are very recent and differ with respect to the coverage of environmental objectives and budgetary items, the underpinning methodologies, the governance and transparency and accountability settings.

As regards the coverage of environmental objectives, Ireland and Sweden report mainly climate-change mitigation measures, while Finland presents appropriations for renewable energy, emission reductions, biodiversity and environmental protection. Meanwhile, Italy tags expenditure based on the UN Classifications of Environmental Protection Activities (CEPA) and Resource Management Activities (CReMA), covering a quite comprehensive number of environmental objectives. Drawing on the EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities, France covers climate change mitigation, climate change adaptation, water resource management, circular economy and waste management, pollution abatement, biodiversity and landscape protection. The EU budget covers, instead, climate change, biodiversity and clean air.

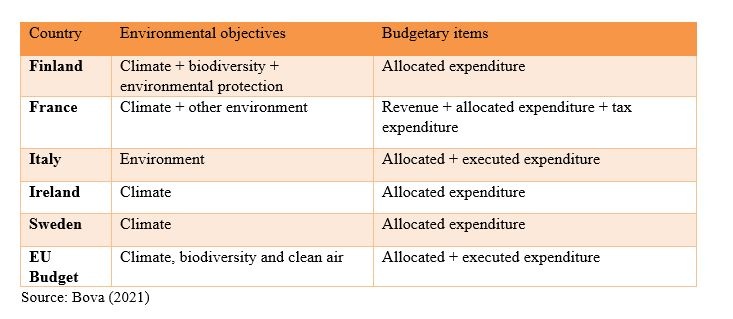

As regards the coverage of budgetary items, France looks systematically at planned expenditure, earmarked-revenue and some tax expenditures of the State budget. Meanwhile, Italy tracks planned and executed expenditure of the central government and provides information on tax expenditure in reports produced by the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Environment. Ireland, Sweden and Finland, instead, present specific expenditure allocations in their budgets; while, the EU presents green allocations for planned and executed expenditure in the draft budget and execution report, respectively (see Table).

Table 1: Coverage of environmental objectives and budgetary items

Methodologies to assess what is green vary from a fully-fledged tagging approach to lighter forms of tagging. France tags quite comprehensively favourable, unfavourable and neutral items by budgetary mission and environmental objective. This approach is set to be expanded to account for different degrees of green, going from a -1 coefficient to a 1, 2 and 3 coefficients, according to the degree at which the item contributes to environmental objectives, including in an unfavourable way. Italy assigns percentages based on the green content of a budgetary programme by environmental objectives of the CEPA or CReMa classifications. Ireland tracks climate-related appropriations through a detailed examination of content. Finland and Sweden conduct a sort of ‘light tagging’ whereby they only present those budgetary allocations that are included in the budget for an explicit environmental purpose. Finally, to track climate expenditures, the Commission uses the “EU Climate markers”, based on the Rio markers methodology, assigning a full (100%) or a partial (40%) or a null (0%) contribution to the climate and biodiversity objectives at the lowest possible level of expenditure.

Only few methodologies include the treatment of unfavourable (‘brown’) spending. France conducts a brown tagging of its budgetary items, even for those whose environmental impacts are usually considered green. The Italian Ministry of Environment publishes an annual publication of all environmentally-related subsidies, including harmful and favourable ones. The Irish Central Statistical Office publishes reports on fossil fuel subsidies; while Finland includes in its budget chapter on climate change and sustainable development a qualitative assessment of environmentally harmful subsidies with an estimate of their amount.

As regards the governance, in all practices examined the Ministry of Finance takes the lead and coordinates the entire process. Then, the governance can rely on a more or less centralised structure, depending on the involvement of line ministries. In France, the General Inspectorate of Finances (IGF) and the General Council for the Environment and Sustainable Development (CGEDD) have developed the green budgeting methodology. The IGF is in charge of drafting the green budgeting report, which is an annex to the draft budget, based on discussions with line ministries and agencies. In Ireland, the climate action unit at the Department of Public Expenditure and Reform (DPER) performs the climate tracking of expenditure, working closely with line ministries. In Italy, a memorandum provides a detailed methodology to guide line ministries in the assessment of the greenness of items. Based on this, every year all administrations have to report the actual share of environmental expenditure for each budgetary action; this information is then reviewed by the Ministry of Finance. In Finland, each year at the onset of the budget preparation, the Ministry of Finance issues an instruction letter to ministries on how to include in their proposals an analysis of their appropriations and connections with sustainable development. Then the Ministry of Finance drafts the chapter in the budget. In Sweden, information on green taxes and expenditures as well as the assessment of potential impacts of reforms are provided based on the collaborative work among ministries and governmental agencies. For the EU budget, the Climate and the Budget Directorates General (DG) lead the work on the methodology and reporting, while the Budget DG steers the discussion on green expenditures. The markers are assigned by the lead DG at the most appropriate level of programme depending on specific design and management modes of programmes.

To support governments in their green budgeting practices, some countries have recently established independent environmental or climate institutions that operate as ‘environmental watchdogs’. These environmental institutions provide expert advice to governments and are involved in the green budgeting work to different degrees. In France, the Climate Council plays a scientific role and was formally consulted on the proposed green budgeting methodology, jointly with the National Council for the Ecological Transition and the Committee for the Green Economy. The Irish Climate change advisory Council offers recommendations to the government, including on the methodology used for green tagging, with a sort of ‘comply and explain’ principle binding the government to either follow the recommendation or to publicly explain the reasons for not following the recommendation. In Finland, the Climate Change Panel gives recommendations to the government as regards its policymaking on climate issues. The Swedish Climate Policy Council contributes to the analyses contained in the budget bill, and more broadly, provides evaluations of the government’s climate policy to assess its alignment with the climate goals established by the parliament and the government. Within its mandate, the council is also in charge of evaluating the bases and models on which the Government builds its policy as well as the impacts of specific policies. In Denmark, the Climate Council is charged with providing advice on how to achieve the climate objectives and provides an assessment on the socio-economic costs of climate policies.

While these incipient approaches point to a strong commitment towards greening budgetary policies, the institutional set-up could be strengthened to ensure transparency and accountability and to limit as much as possible green washing. In fact, in most countries reviewed, there does not seem to be an independent validation process of the green items by auditors or third parties, who could provide an independent opinion on whether what is claimed to be green is really green. In Italy, the budget execution document is validated by the court of auditors and, within this, is also the document on environmental expenditure execution. As regards evaluations of specific policies, the Irish government undertakes regular, in-depth assessments of specific spending programmes, including climate related expenditure programmes. For the EU budget, the European Court of Auditors has issued some regular assessments for climate tracking and will soon issue one for biodiversity, both at EU budget level and for specific programmes. In most cases, public attention to these reports remains limited. In Italy, there is an obligation to present the green budgeting reports to the national parliament as part of the annual budgetary cycle. However, these presentations do not seem to play a strong role in informing budgetary policies. In Ireland, the programmes related to green budgeting are discussed and voted in the parliament. In France, the parliament seems to be quite attentive to the issue as it mandated the report which is discussed within the budgetary discussions.

Conclusion

By presenting new evidence on green budgeting practices, this note contributes to building an informed view and promote best practice in the way countries are approaching green budgeting. Looking at a limited sample of national and EU practices, this note refines and clarifies concepts and underlines challenges that national authorities encounter when trying to assess the greenness of their budgets. It reports evidence on the following elements necessary to define and implement green budgeting: the coverage, the methodology for identifying the contributions to green objectives, the governance and transparency and accountability. By expanding on the institutional set up within which these practices are framed, the note also highlights weaknesses in terms of transparency and accountability.

While assessing the greenness of a budget is a fundamental condition for greening a country ‘s economy, this is only a starting point. From a more informed view of how we shape our budgetary policies, then government can conduct a profound green mainstreaming of their budgets, better aligning measures to environmental goals. This said, while the budget is a crucial tool for the greening of the economy, it is certainly not the only one. Attention must indeed be paid to other policies and to regulations as these could shape the economy in a similarly substantial way.